Canberra Bird Notes Is Published Quarterly by the Canberra Ornithologists Group Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Whistler3 Frontcover

The Whistler is the occasionally issued journal of the Hunter Bird Observers Club Inc. ISSN 1835-7385 The aims of the Hunter Bird Observers Club (HBOC), which is affiliated with Bird Observation and Conservation Australia, are: To encourage and further the study and conservation of Australian birds and their habitat To encourage bird observing as a leisure-time activity HBOC is administered by a Committee: Executive: Committee Members: President: Paul Baird Craig Anderson Vice-President: Grant Brosie Liz Crawford Secretary: Tom Clarke Ann Lindsey Treasurer: Rowley Smith Robert McDonald Ian Martin Mick Roderick Publication of The Whistler is supported by a Sub-committee: Mike Newman (Joint Editor) Harold Tarrant (Joint Editor) Liz Crawford (Production Manager) Chris Herbert (Cover design) Liz Huxtable Ann Lindsey Jenny Powers Mick Roderick Alan Stuart Authors wishing to submit manuscripts for consideration for publication should consult Instructions for Authors on page 61 and submit to the Editors: Mike Newman [email protected] and/or Harold Tarrant [email protected] Authors wishing to contribute articles of general bird and birdwatching news to the club newsletter, which has 6 issues per year, should submit to the Newsletter Editor: Liz Crawford [email protected] © Hunter Bird Observers Club Inc. PO Box 24 New Lambton NSW 2305 Website: www.hboc.org.au Front cover: Australian Painted Snipe Rostratula australis – Photo: Ann Lindsey Back cover: Pacific Golden Plover Pluvialis fulva - Photo: Chris Herbert The Whistler is proudly supported by the Hunter-Central Rivers Catchment Management Authority Editorial The Whistler 3 (2009): i-ii The Whistler – Editorial The Editors are pleased to provide our members hopefully make good reading now, but will and other ornithological enthusiasts with the third certainly provide a useful point of reference for issue of the club’s emerging journal. -

Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat

Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Dedicated bird enthusiasts have kindly contributed to this sequence of 106 bird species spotted in the habitat over the last few years Kookaburra Red-browed Finch Black-faced Cuckoo- shrike Magpie-lark Tawny Frogmouth Noisy Miner Spotted Dove [1] Crested Pigeon Australian Raven Olive-backed Oriole Whistling Kite Grey Butcherbird Pied Butcherbird Australian Magpie Noisy Friarbird Galah Long-billed Corella Eastern Rosella Yellow-tailed black Rainbow Lorikeet Scaly-breasted Lorikeet Cockatoo Tawny Frogmouth c Noeline Karlson [1] ( ) Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Variegated Fairy- Yellow Faced Superb Fairy-wren White Cheeked Scarlet Honeyeater Blue-faced Honeyeater wren Honeyeater Honeyeater White-throated Brown Gerygone Brown Thornbill Yellow Thornbill Eastern Yellow Robin Silvereye Gerygone White-browed Eastern Spinebill [2] Spotted Pardalote Grey Fantail Little Wattlebird Red Wattlebird Scrubwren Willie Wagtail Eastern Whipbird Welcome Swallow Leaden Flycatcher Golden Whistler Rufous Whistler Eastern Spinebill c Noeline Karlson [2] ( ) Common Sea and shore birds Silver Gull White-necked Heron Little Black Australian White Ibis Masked Lapwing Crested Tern Cormorant Little Pied Cormorant White-bellied Sea-Eagle [3] Pelican White-faced Heron Uncommon Sea and shore birds Caspian Tern Pied Cormorant White-necked Heron Great Egret Little Egret Great Cormorant Striated Heron Intermediate Egret [3] White-bellied Sea-Eagle (c) Noeline Karlson Uncommon Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Grey Goshawk Australian Hobby -

National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera Phrygia)

National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia) April 2016 1 The Species Profile and Threats Database pages linked to this recovery plan is obtainable from: http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2016. The National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia) is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This report should be attributed as ‘National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia), Commonwealth of Australia 2016’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright, [name of third party] ’. Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. Image credits Front Cover: Regent honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, NSW. (© Copyright, Dean Ingwersen). 2 -

Yarra's Topography Is Gently Undulating, Which Is Characteristic of the Western Basalt Plains

Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 Acknowledgement of country ............................................................................................................................ 3 Message from the Mayor ................................................................................................................................... 4 Vision and goals ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 Nature in Yarra .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Policy and strategy relevant to natural values ................................................................................................. 27 Legislative context ........................................................................................................................................... 27 What does Yarra do to support nature? .......................................................................................................... 28 Opportunities and challenges for nature ......................................................................................................... -

Social Behaviour and Breeding Biology of the Yeliow-Rumped Thornbill

Social Behaviour and Breeding Biology of the Yeliow-Rumped Thornbill Daniel Ebert A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of hilosophy of The Australian National University April 2004 Declaration The research presented in this thesis is my own original work and no part has been submitted for a previous degree. Signed Daniel Ebert April 2004 Dedication In memory of Anjeli Catherine Nathan 18 March 1975 - 3 November 1999 Acknowledgements This thesis was a work in progress, or not, for some years and many people made significant contributions of supervision, assistance or support. My supervisor, Rob Magrath, and Andrew Cockburn and David Green were instrumental in promoting thombill research as a worthwhile pursuit. I thank them for their contributions to the formulation of this project and their interest in my work. Rob Magrath’s particular combination of insight, knowledge and patience was invaluable throughout this study. I am also grateful for the general advice and guidance of Rob Heinsohn and Sarah Legge. This project involved many early morning mist-netting sessions which would have been even more “miss” than “hit” without the enthusiastic assistance of numerous volunteers. David Green, Mike Double, James Nicholls, Sarah Legge, Anjeli Nathan, Janet Gardner, Nie MacGregor, Rob Heinsohn, Rob Magrath, Andrew Cockburn and Peter Marsack all cheerfully participated in the usually unrewarding exercise of netting thombills in the mist and cold. I’m especially grateful to Steve Murphy for his competence and enthusiasm in the field and his impressive ability to find thombill nests after half an hour of “training”. Minisatellite DNA fingerprinting is an error-prone and frustrating procedure usually requiring good fortune as well as good management for success. -

Australia's Biodiversity and Climate Change

Australia’s Biodiversity and Climate Change A strategic assessment of the vulnerability of Australia’s biodiversity to climate change A report to the Natural Resource Management Ministerial Council commissioned by the Australian Government. Prepared by the Biodiversity and Climate Change Expert Advisory Group: Will Steffen, Andrew A Burbidge, Lesley Hughes, Roger Kitching, David Lindenmayer, Warren Musgrave, Mark Stafford Smith and Patricia A Werner © Commonwealth of Australia 2009 ISBN 978-1-921298-67-7 Published in pre-publication form as a non-printable PDF at www.climatechange.gov.au by the Department of Climate Change. It will be published in hard copy by CSIRO publishing. For more information please email [email protected] This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the: Commonwealth Copyright Administration Attorney-General's Department 3-5 National Circuit BARTON ACT 2600 Email: [email protected] Or online at: http://www.ag.gov.au Disclaimer The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for Climate Change and Water and the Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts. Citation The book should be cited as: Steffen W, Burbidge AA, Hughes L, Kitching R, Lindenmayer D, Musgrave W, Stafford Smith M and Werner PA (2009) Australia’s biodiversity and climate change: a strategic assessment of the vulnerability of Australia’s biodiversity to climate change. -

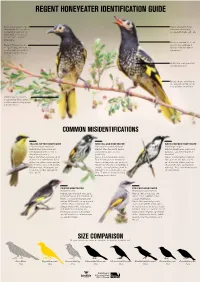

Regent Honeyeater Identification Guide

REGENT HONEYEATER IDENTIFICATION GUIDE Broad patch of bare warty Males call prominently, skin around the eye, which whereas females only is smaller in young birds occasionally make soft calls. and females. Best seen at close range or with binoculars. Plumage around the head Regent Honeyeaters are and neck is solid black 20-24 cm long, with females giving a slightly hooded smaller and having duller appearance. plumage than the males. Distinctive scalloped (not streaked) breast. Broad stripes of yellow in the wing when folded, and very prominent in flight. From below the tail is a bright yellow. From behind it’s black bordered by bright yellow feathers. COMMON MISIDENTIFICATIONS YELLOW-TUFTED HONEYEATER NEW HOLLAND HONEYEATER WHITE-CHEEKED HONEYEATER Lichenostomus melanops Phylidonyris novaehollandiae Phylidonyris niger Habitat: Box-Gum-Ironbark Habitat: Woodland with heathy Habitat: Heathlands, parks and woodlands and forest with a understorey, gardens and gardens, less commonly open shrubby understorey. parklands. woodland. Notes: Common, sedentary bird Notes: Often misidentified as a Notes: Similar to New Holland of temperate woodlands. Has a Regent Honeyeater; commonly Honeyeaters, but have a large distinctive yellow crown and ear seen in urban parks and gardens. patch of white feathers in their tuft in a black face, with a bright Distinctive white breast with black cheek and a dark eye (no white yellow throat. Underparts are streaks, several patches of white eye ring). Also have white breast plain dirty yellow, upperparts around the face, and a white eye streaked black. olive-green. ring. Tend to be in small, noisy and aggressive flocks. PAINTED HONEYEATER CRESCENT HONEYEATER Grantiella picta Phylidonyris pyrrhopterus Habitat: Box-Ironbark woodland, Habitat: Wetter habitats like particularly with fruiting mistletoe forest, dense woodland and Notes: A seasonal migrant, only coastal heathlands. -

The Role of Habitat Variability and Interactions Around Nesting Cavities in Shaping Urban Bird Communities

The role of habitat variability and interactions around nesting cavities in shaping urban bird communities Andrew Munro Rogers BSc, MSc Photo: A. Rogers A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2018 School of Biological Sciences Andrew Rogers PhD Thesis Thesis Abstract Inter-specific interactions around resources, such as nesting sites, are an important factor by which invasive species impact native communities. As resource availability varies across different environments, competition for resources and invasive species impacts around those resources change. In urban environments, changes in habitat structure and the addition of introduced species has led to significant changes in species composition and abundance, but the extent to which such changes have altered competition over resources is not well understood. Australia’s cities are relatively recent, many of them located in coastal and biodiversity-rich areas, where conservation efforts have the opportunity to benefit many species. Australia hosts a very large diversity of cavity-nesting species, across multiple families of birds and mammals. Of particular interest are cavity-breeding species that have been significantly impacted by the loss of available nesting resources in large, old, hollow- bearing trees. Cavity-breeding species have also been impacted by the addition of cavity- breeding invasive species, increasing the competition for the remaining nesting sites. The results of this additional competition have not been quantified in most cavity breeding communities in Australia. Our understanding of the importance of inter-specific interactions in shaping the outcomes of urbanization and invasion remains very limited across Australian communities. This has led to significant gaps in the understanding of the drivers of inter- specific interactions and how such interactions shape resource use in highly modified environments. -

Catalogue of Protozoan Parasites Recorded in Australia Peter J. O

1 CATALOGUE OF PROTOZOAN PARASITES RECORDED IN AUSTRALIA PETER J. O’DONOGHUE & ROBERT D. ADLARD O’Donoghue, P.J. & Adlard, R.D. 2000 02 29: Catalogue of protozoan parasites recorded in Australia. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 45(1):1-164. Brisbane. ISSN 0079-8835. Published reports of protozoan species from Australian animals have been compiled into a host- parasite checklist, a parasite-host checklist and a cross-referenced bibliography. Protozoa listed include parasites, commensals and symbionts but free-living species have been excluded. Over 590 protozoan species are listed including amoebae, flagellates, ciliates and ‘sporozoa’ (the latter comprising apicomplexans, microsporans, myxozoans, haplosporidians and paramyxeans). Organisms are recorded in association with some 520 hosts including mammals, marsupials, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish and invertebrates. Information has been abstracted from over 1,270 scientific publications predating 1999 and all records include taxonomic authorities, synonyms, common names, sites of infection within hosts and geographic locations. Protozoa, parasite checklist, host checklist, bibliography, Australia. Peter J. O’Donoghue, Department of Microbiology and Parasitology, The University of Queensland, St Lucia 4072, Australia; Robert D. Adlard, Protozoa Section, Queensland Museum, PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia; 31 January 2000. CONTENTS the literature for reports relevant to contemporary studies. Such problems could be avoided if all previous HOST-PARASITE CHECKLIST 5 records were consolidated into a single database. Most Mammals 5 researchers currently avail themselves of various Reptiles 21 electronic database and abstracting services but none Amphibians 26 include literature published earlier than 1985 and not all Birds 34 journal titles are covered in their databases. Fish 44 Invertebrates 54 Several catalogues of parasites in Australian PARASITE-HOST CHECKLIST 63 hosts have previously been published. -

South Eastern Australia Temperate Woodlands

Conservation Management Zones of Australia South Eastern Australia Temperate Woodlands Prepared by the Department of the Environment Acknowledgements This project and its associated products are the result of collaboration between the Department of the Environment’s Biodiversity Conservation Division and the Environmental Resources Information Network (ERIN). Invaluable input, advice and support were provided by staff and leading researchers from across the Department of Environment (DotE), Department of Agriculture (DoA), the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and the academic community. We would particularly like to thank staff within the Wildlife, Heritage and Marine Division, Parks Australia and the Environment Assessment and Compliance Division of DotE; Nyree Stenekes and Robert Kancans (DoA), Sue McIntyre (CSIRO), Richard Hobbs (University of Western Australia), Michael Hutchinson (ANU); David Lindenmayer and Emma Burns (ANU); and Gilly Llewellyn, Martin Taylor and other staff from the World Wildlife Fund for their generosity and advice. Special thanks to CSIRO researchers Kristen Williams and Simon Ferrier whose modelling of biodiversity patterns underpinned identification of the Conservation Management Zones of Australia. Image Credits Front Cover: Yanga or Murrumbidgee Valley National Park – Paul Childs/OEH Page 4: River Red Gums (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) – Allan Fox Page 10: Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia) – Trent Browning Page 16: Gunbower Creek – Arthur Mostead Page 19: Eastern Grey -

Diverse Interactions, Including Hybridisation, Between Brown and Inland Thornbills in South Australia

18 South Australian Ornithologist 41 (1) Diverse interactions, including hybridisation, between Brown and Inland Thornbills in South Australia ANDREW BLACK, PHILIPPA HORTON AND LEO JOSEPH Abstract relative) the Mountain Thornbill, A. katherina, of the Wet Tropics rainforests; the Inland Thornbill, A. apicalis, widespread across southern and Brown and Inland Thornbills have three zones of central Australian semi-arid and arid zones and contact in South Australia. Two of these involve the more mesic south-west of Western Australia; the Mount Lofty Ranges Brown Thornbill, which and the Tasmanian Thornbill, A. ewingi, endemic hybridises extensively with the Inland Thornbill in to Tasmania and its larger offshore islands. coastal shrublands and mangroves of eastern Gulf St Vincent, and which forms an apparently narrow Though the Brown and Inland Thornbills are not hybrid zone near Meningie with Inland Thornbills of sister species, the nature of interactions between the Upper South-East of South Australia. The third them where they approach each other in several zone involves Brown Thornbills of the South-East parts of their ranges has long been a contentious of South Australia and the Inland Thornbill, again area of research (e.g. Mayr and Serventy 1938, its Upper South-East population. This is evidently a Boles 1983, Schodde and Mason 1999). This paper broad zone of overlap without interbreeding. Closer further addresses the issue. study of the Gulf St Vincent hybrid zone revealed a variety of hybrid phenotypes but no parental forms. Across their full geographic ranges three major Most of the hybrid phenotypes resemble Inland zones of interaction between Brown and Inland Thornbills while some resemble Brown Thornbills of Thornbills have been recognised: 1) the Upper the Mount Lofty Ranges or of the South-East of South South-East of South Australia (SA) and north- Australia. -

Eastern Australia: October-November 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN AUSTRALIA: From Top to Bottom 23rd October – 11th November 2016 The bird of the trip, the very impressive POWERFUL OWL Tour Leader: Laurie Ross All photos in this report were taken by Laurie Ross/Tropical Birding. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 INTRODUCTION The Eastern Australia Set Departure Tour introduces a huge amount of new birds and families to the majority of the group. We started the tour in Cairns in Far North Queensland, where we found ourselves surrounded by multiple habitats from the tidal mudflats of the Cairns Esplanade, the Great Barrier Reef and its sandy cays, lush lowland and highland rainforests of the Atherton Tablelands, and we even made it to the edge of the Outback near Mount Carbine; the next leg of the tour took us south to Southeast Queensland where we spent time in temperate rainforests and wet sclerophyll forests within Lamington National Park. The third, and my favorite leg, of the tour took us down to New South Wales, where we birded a huge variety of new habitats from coastal heathland to rocky shorelines and temperate rainforests in Royal National Park, to the mallee and brigalow of Inland New South Wales. The fourth and final leg of the tour saw us on the beautiful island state of Tasmania, where we found all 13 “Tassie” endemics. We had a huge list of highlights, from finding a roosting Lesser Sooty Owl in Malanda; to finding two roosting Powerful Owls near Brisbane; to having an Albert’s Lyrebird walk out in front of us at O Reilly’s; to seeing the rare and endangered Regent Honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, and finding the endangered Swift Parrot on Bruny Island, in Tasmania.