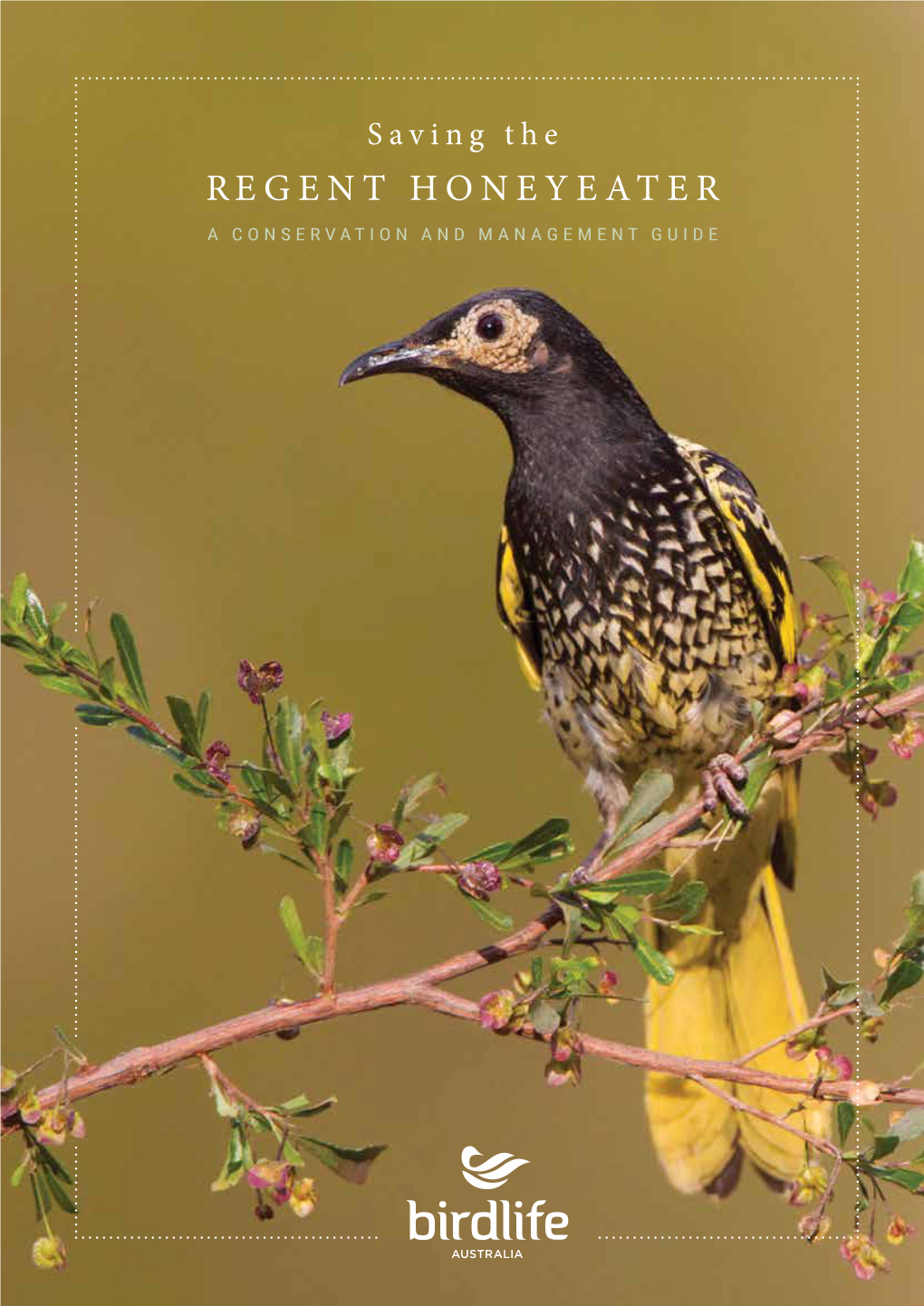

Saving the REGENT HONEYEATER a CONSERVATION and MANAGEMENT GUIDE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lake Pinaroo Ramsar Site

Ecological character description: Lake Pinaroo Ramsar site Ecological character description: Lake Pinaroo Ramsar site Disclaimer The Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW (DECC) has compiled the Ecological character description: Lake Pinaroo Ramsar site in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. DECC does not accept responsibility for any inaccurate or incomplete information supplied by third parties. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. Readers should seek appropriate advice about the suitability of the information to their needs. © State of New South Wales and Department of Environment and Climate Change DECC is pleased to allow the reproduction of material from this publication on the condition that the source, publisher and authorship are appropriately acknowledged. Published by: Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW 59–61 Goulburn Street, Sydney PO Box A290, Sydney South 1232 Phone: 131555 (NSW only – publications and information requests) (02) 9995 5000 (switchboard) Fax: (02) 9995 5999 TTY: (02) 9211 4723 Email: [email protected] Website: www.environment.nsw.gov.au DECC 2008/275 ISBN 978 1 74122 839 7 June 2008 Printed on environmentally sustainable paper Cover photos Inset upper: Lake Pinaroo in flood, 1976 (DECC) Aerial: Lake Pinaroo in flood, March 1976 (DECC) Inset lower left: Blue-billed duck (R. Kingsford) Inset lower middle: Red-necked avocet (C. Herbert) Inset lower right: Red-capped plover (C. Herbert) Summary An ecological character description has been defined as ‘the combination of the ecosystem components, processes, benefits and services that characterise a wetland at a given point in time’. -

Indonesia's Exquisite Birds of Paradise

INDONESIA'S EXQUISITE BIRDS OF PARADISE Whether you are a mere nestling who is new to bird watching, a Halmehera: Standard-wing (Wallace’s) Bird-of fully-fledged birder, or a seasoned twitcher, this 10-day (9-night) ornithological adventure through the remote, rainforest-clad islands of northern Raja Ampat and North Maluku, which includes a two-night stay at the famed Weda Resort on Halmahera, is a fantastic opportunity to add some significant numbers to your life lists. No other feathered family is as beautiful, or displays such diversity of plumage, extravagant decoration, and courtship behaviour as the ostentatious Bird of Paradise. In the company of our guest expert, Dr. Kees Groeneboer, we will be in hot pursuit of as many as six or seven species of these fabled shapeshifters, which strut, dazzle and dance in costumes worthy of the stage. -Paradise, Paradise Crow. Special birds in the Weda-Forest of Raja Ampat is one of the most noteworthy ecological niches on Halmahera Moluccan Goshawk, Moluccan Scrubfowl, Bare-eyed the planet, where you can snorkel within a below-surface world Rail, Drummer Rail, Scarletbreasted Fruit-Dove, Blue-capped reminiscent of a living kaleidoscope, while marveling at Fruit-Dove, Cinnamon-bellied Imperial Pigeon, Chattering Lory, above-surface views – and birds, which are among the most White (Alba) Cockatoo, Moluccan Cuckoo, Goliath Coucal, Blue stunning that you are likely to behold in a lifetime. Meanwhile, and-white Kingfisher, Sombre Kingfisher, Azure (Purple) Halmahera, in the North Maluku province, is where some of the Dollarbird, Ivory-breasted Pitta, Halmahera Cuckooshrike, world’s rarest and least-known birds occur. -

A 'Slow Pace of Life' in Australian Old-Endemic Passerine Birds Is Not Accompanied by Low Basal Metabolic Rates

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers: part A Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health 1-1-2016 A 'slow pace of life' in Australian old-endemic passerine birds is not accompanied by low basal metabolic rates Claus Bech University of Wollongong Mark A. Chappell University of Wollongong, [email protected] Lee B. Astheimer University of Wollongong, [email protected] Gustavo A. Londoño Universidad Icesi William A. Buttemer University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/smhpapers Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Bech, Claus; Chappell, Mark A.; Astheimer, Lee B.; Londoño, Gustavo A.; and Buttemer, William A., "A 'slow pace of life' in Australian old-endemic passerine birds is not accompanied by low basal metabolic rates" (2016). Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers: part A. 3841. https://ro.uow.edu.au/smhpapers/3841 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] A 'slow pace of life' in Australian old-endemic passerine birds is not accompanied by low basal metabolic rates Abstract Life history theory suggests that species experiencing high extrinsic mortality rates allocate more resources toward reproduction relative to self-maintenance and reach maturity earlier ('fast pace of life') than those having greater life expectancy and reproducing at a lower rate ('slow pace of life'). Among birds, many studies have shown that tropical species have a slower pace of life than temperate-breeding species. -

NOT WANTED in Tasmania Indian Mynas Are a Serious Pest In

Indian myna Acridotheres tristis EMERGING INVASIVE SPECIES NOT WANTED Prompt action is vital in Tasmania Indian mynas are now well established in eastern Australia Indian mynas are a and continue to spread serious pest in throughout the country. Tasmania does not currently Australia and are have an established population considered one of Indian mynas. of the world's 100 worst Since 2003, there have been six confirmed incursions of Indian invasive species. mynas in Tasmania. In each case, DPIPWE has responded and successfully removed the birds. Image: Chris Tzaros History of a pest What can we do? Natural range: Indian mynas Acridotheres tristis are Asia highly invasive birds that can Biosecurity Tasmania will Middle East rapidly colonise new areas. First respond to Indian myna India introduced to Melbourne in the incursions to prevent 1860s, mynas are now found along establishment of this invasive Risk to Tasmania: the east coast of Australia from species in Tasmania. Extreme Victoria to Queensland. The Tasmanian public Main impacts: Indian mynas are highly should be on high alert Native wildlife (esp. native birds) aggressive and pose a threat to for this species and Agriculture wildlife, particularly birds, by report all sightings. Spread disease competing for food and nesting Public nuisance resources. They can also damage Early detection to allow rapid horticultural and cereal crops, response to incursions is vital. Status: spread weeds and be a public Indian mynas are a restricted nuisance by nesting in building animal under the Nature cavities, causing noise at roosting Conservation Act 2002 sites, swooping people and transmitting bird mites. -

Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat

Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Dedicated bird enthusiasts have kindly contributed to this sequence of 106 bird species spotted in the habitat over the last few years Kookaburra Red-browed Finch Black-faced Cuckoo- shrike Magpie-lark Tawny Frogmouth Noisy Miner Spotted Dove [1] Crested Pigeon Australian Raven Olive-backed Oriole Whistling Kite Grey Butcherbird Pied Butcherbird Australian Magpie Noisy Friarbird Galah Long-billed Corella Eastern Rosella Yellow-tailed black Rainbow Lorikeet Scaly-breasted Lorikeet Cockatoo Tawny Frogmouth c Noeline Karlson [1] ( ) Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Variegated Fairy- Yellow Faced Superb Fairy-wren White Cheeked Scarlet Honeyeater Blue-faced Honeyeater wren Honeyeater Honeyeater White-throated Brown Gerygone Brown Thornbill Yellow Thornbill Eastern Yellow Robin Silvereye Gerygone White-browed Eastern Spinebill [2] Spotted Pardalote Grey Fantail Little Wattlebird Red Wattlebird Scrubwren Willie Wagtail Eastern Whipbird Welcome Swallow Leaden Flycatcher Golden Whistler Rufous Whistler Eastern Spinebill c Noeline Karlson [2] ( ) Common Sea and shore birds Silver Gull White-necked Heron Little Black Australian White Ibis Masked Lapwing Crested Tern Cormorant Little Pied Cormorant White-bellied Sea-Eagle [3] Pelican White-faced Heron Uncommon Sea and shore birds Caspian Tern Pied Cormorant White-necked Heron Great Egret Little Egret Great Cormorant Striated Heron Intermediate Egret [3] White-bellied Sea-Eagle (c) Noeline Karlson Uncommon Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Grey Goshawk Australian Hobby -

Management and Breeding of Birds of Paradise (Family Paradisaeidae) at the Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation

Management and breeding of Birds of Paradise (family Paradisaeidae) at the Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation. By Richard Switzer Bird Curator, Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation. Presentation for Aviary Congress Singapore, November 2008 Introduction to Birds of Paradise in the Wild Taxonomy The family Paradisaeidae is in the order Passeriformes. In the past decade since the publication of Frith and Beehler (1998), the taxonomy of the family Paradisaeidae has been re-evaluated considerably. Frith and Beehler (1998) listed 42 species in 17 genera. However, the monotypic genus Macgregoria (MacGregor’s Bird of Paradise) has been re-classified in the family Meliphagidae (Honeyeaters). Similarly, 3 species in 2 genera (Cnemophilus and Loboparadisea) – formerly described as the “Wide-gaped Birds of Paradise” – have been re-classified as members of the family Melanocharitidae (Berrypeckers and Longbills) (Cracraft and Feinstein 2000). Additionally the two genera of Sicklebills (Epimachus and Drepanornis) are now considered to be combined as the one genus Epimachus. These changes reduce the total number of genera in the family Paradisaeidae to 13. However, despite the elimination of the 4 species mentioned above, 3 species have been newly described – Berlepsch's Parotia (P. berlepschi), Eastern or Helen’s Parotia (P. helenae) and the Eastern or Growling Riflebird (P. intercedens). The Berlepsch’s Parotia was once considered to be a subspecies of the Carola's Parotia. It was previously known only from four female specimens, discovered in 1985. It was rediscovered during a Conservation International expedition in 2005 and was photographed for the first time. The Eastern Parotia, also known as Helena's Parotia, is sometimes considered to be a subspecies of Lawes's Parotia, but differs in the male’s frontal crest and the female's dorsal plumage colours. -

THE HONEYEATERS of KANGAROO ISLAND HUGH FOB,D Accepted August

134 SOUTH AUsTRALIAN ORNITHOLOGIST, 21 THE HONEYEATERS OF KANGAROO ISLAND HUGH FOB,D Accepted August. 1976 Kangaroo Island is the third largest of Aus In the present paper I discuss morphological tralia's islands (4,500 sq. km) and has been and ecological differences between populations separated from the neighbouring Fleurieu of several species of honeyeaters from Kangaroo Peninsula for 10,000 years (Abbott 1973). A Island and the Fleurieu Peninsula respectively, mere 14 km separates island from mainland; and speculate on how these differences origin but the island has a distinct avifauna and lacks ated. many of the mainland species. This paucity of DIFFERENCES IN PLUMAGE species has been attributed to extinction after The Kangaroo Island population of Purple isolation and failure to recolonise (Abbott gaped Honeyeater was described as larger and 1974, 1976), and to lack of suitable habitat brighter than the mainland population by (Ford and Paton 1975). Mathews (1923-4). Brightness of plumage is a Nine species of honeyeaters are resident on very subjective characteristic, and in my opinion Kangaroo Island. The Purple-gaped Honey Purple-gaped Honeyeaters on Kangaroo Island eater Lichenostomus cratitius (formerly Meli are, if anything, duller than mainland ones. phaga cratitia) was described as a distinct sub Condon (1951) says that the gape of this species by Mathews (1923-24); and Keast species is invariably yellow on Kangaroo Island (1961) mentions that six other species differ in instead of lilac, although he later comments a minor way from mainland populations and that lilac-gaped individuals do occur on the may merit subspecific status. -

Birding Oxley Creek Common Brisbane, Australia

Birding Oxley Creek Common Brisbane, Australia Hugh Possingham and Mat Gilfedder – January 2011 [email protected] www.ecology.uq.edu.au 3379 9388 (h) Other photos, records and comments contributed by: Cathy Gilfedder, Mike Bennett, David Niland, Mark Roberts, Pete Kyne, Conrad Hoskin, Chris Sanderson, Angela Wardell-Johnson, Denis Mollison. This guide provides information about the birds, and how to bird on, Oxley Creek Common. This is a public park (access restricted to the yellow parts of the map, page 6). Over 185 species have been recorded on Oxley Creek Common in the last 83 years, making it one of the best birding spots in Brisbane. This guide is complimented by a full annotated list of the species seen in, or from, the Common. How to get there Oxley Creek Common is in the suburb of Rocklea and is well signposted from Sherwood Road. If approaching from the east (Ipswich Road side), pass the Rocklea Markets and turn left before the bridge crossing Oxley Creek. If approaching from the west (Sherwood side) turn right about 100 m after the bridge over Oxley Creek. The gate is always open. Amenities The main development at Oxley Creek Common is the Red Shed, which is beside the car park (plenty of space). The Red Shed has toilets (composting), water, covered seating, and BBQ facilities. The toilets close about 8pm and open very early. The paths are flat, wide and easy to walk or cycle. When to arrive The diversity of waterbirds is a feature of the Common and these can be good at any time of the day. -

DRAFT Biodiversity Action Plan 2021 - 2026

DRAFT Biodiversity Action Plan 2021 - 2026 Prepared by: Infrastructure Services & Planning and Ecology Australia Contents Acknowledgments 4 A Vision for the Future 5 Introduction 6 Summary of state and extent of biodiversity in Greater Dandenong 7 Study area 7 Flora and fauna 9 Existing landscape habitat types 10 Key threats to local biodiversity values 12 Habitat assessments 15 Habitat connectivity for icon species 16 Community consultation and engagement 18 Biodiversity legislation considerations 20 Council strategies 22 Actions 23 Protection and enhancement of existing biodiversity values 24 Improving knowledge of biodiversity values 26 Facilitating and encouraging biodiversity conservation and enhancement on private land 27 Managing threatening processes 28 Community engagement and education 30 References 32 Tables Table 1 Summary of most common reasons why biodiversity is considered important from online survey and examples of comments provided 19 Table 2 Commonwealth and Victorian biodiversity legislation 20 Plates Plate 1 City of Greater Dandenong LGA and municipality study area, including surrounding areas of biodiversity significance. 8 Plate 2 Potential connectivity sites within Greater Dandenong for all five icon species 17 DRAFT City of Greater Dandenong Biodiversity Action Plan 2021 – 2026 ii Appendices Appendix 1 Vegetation coverage across the City of Greater Dandenong pre 1750 (left) and today (right). 34 Appendix 2 Fauna species listed as threatened under the EPBC Act 1999 (DAWE 2020), FFG Act 1988 (DELWP 2019b) or the Victorian Threatened Species Advisory List recorded within the City of Greater Dandenong municipality ....................................................................................................... 35 Appendix 3 Flora species listed as threatened under the EPBC Act 1999 (DAWE 2020), FFG Act 1988 (DELWP 2019b) or the Victorian Threatened Species Advisory List recorded within the City of Greater Dandenong municipality ...................................................................................................... -

Brown Honeyeater Lichmera Indistincta Species No.: 597 Band Size: 02 (01) AY

Australian Bird Study Association Inc. – Bird in the Hand (Second Edition), published on www.absa.asn.au - Revised August 2019 Brown Honeyeater Lichmera indistincta Species No.: 597 Band Size: 02 (01) AY Morphometrics: Adult Male Adult Female THL: 30.7 – 36 mm 30.3 – 34.1 mm Wing Length: 54 – 76 mm 53 – 68 mm Wing Span: > 220 mm < 215 mm Tail: 48 – 64 mm 47 – 58 mm Tarsus: 15.8 – 19.5 mm 15.3 – 17.3 mm Weight: 7.9 – 13.6 g 7.0 – 12.1 g Ageing and sexing: Adult Male Adult Female Juvenile Forehead, crown dark brown with thick dark, brown with olive like female, but loose & & nape: brownish-grey fringes or wash or greenish; downy texture; silvery grey; Bill: fully black; black, but often with mostly black with yellow pinkish-white base; -ish tinge near base; Gape black when breeding, but yellow, yellowish white, puffy yellow; yellow or yellowish white pinkish white or buff- when not breeding; yellow; Chin & throat: brownish grey; brownish grey with straw similar to female, but -yellow fringes; looser and downy; Juvenile does not have yellow triangle feather tuft behind eye until about three months after fledging; Immature plumage is very similar to adult female, but may retain juvenile remiges, rectrices and upper wing coverts; Adult plumage is acquired at approximately 15 months - so age adults (2+) and Immatures either (2) or (1) if very young and downy. Apart from plumage differences, males appear considerably larger than females, but there Is a large overlap in most measurements, except in wingspan; Female alone incubates. -

National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera Phrygia)

National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia) April 2016 1 The Species Profile and Threats Database pages linked to this recovery plan is obtainable from: http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2016. The National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia) is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This report should be attributed as ‘National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia), Commonwealth of Australia 2016’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright, [name of third party] ’. Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. Image credits Front Cover: Regent honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, NSW. (© Copyright, Dean Ingwersen). 2 -

Bush Birds Making Your Place Their Place Too

BUSH BIRDS MAKING YOUR PLACE THEIR PLACE TOO This fact sheet explains which bush birds may be present or absent from your place and what you can do to encourage a greater diversity to live with you. The drier, settled areas of southern Tasmania, and whistlers. Some, like Pink Robin and Scrubtit, compared to other places, still have much of their prefer wet forest and others, such as Forty- original bush. In many instances the clearing for spotted Pardalote are rarely seen outside their agriculture and urban development has produced preferred specialist habitat. a mosaic of habitats including highly modified The Yellow-throated Honeyeater needs bush with Some species live in the same bush all year, treeless paddocks through to fully vegetated hills, good structure, as it forages high in trees but nests whilst others migrate in the late autumn to in which many species of birds still thrive. But bird in shrubs close to the ground. increase their foraging range, descend in species begin to decline or will be absent where altitude or cross Bass Strait to spend their intact patches of bush are lost or if this mosaic winter on mainland Australia. Bush habitat also BUSH BIRDS’ HOMES becomes too highly modified. supports birds of prey, water birds in creeks and Just like us, birds have three basic needs: About 60 species of birds live within the bush of wetlands, and a small number of other species 1. Their preferred food. southern Tasmania. Common groups of species using heaths or grasslands on the forest fringe. include honeyeaters, parrots, robins, pardalotes 2.