Bush Birds Making Your Place Their Place Too

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE HONEYEATERS of KANGAROO ISLAND HUGH FOB,D Accepted August

134 SOUTH AUsTRALIAN ORNITHOLOGIST, 21 THE HONEYEATERS OF KANGAROO ISLAND HUGH FOB,D Accepted August. 1976 Kangaroo Island is the third largest of Aus In the present paper I discuss morphological tralia's islands (4,500 sq. km) and has been and ecological differences between populations separated from the neighbouring Fleurieu of several species of honeyeaters from Kangaroo Peninsula for 10,000 years (Abbott 1973). A Island and the Fleurieu Peninsula respectively, mere 14 km separates island from mainland; and speculate on how these differences origin but the island has a distinct avifauna and lacks ated. many of the mainland species. This paucity of DIFFERENCES IN PLUMAGE species has been attributed to extinction after The Kangaroo Island population of Purple isolation and failure to recolonise (Abbott gaped Honeyeater was described as larger and 1974, 1976), and to lack of suitable habitat brighter than the mainland population by (Ford and Paton 1975). Mathews (1923-4). Brightness of plumage is a Nine species of honeyeaters are resident on very subjective characteristic, and in my opinion Kangaroo Island. The Purple-gaped Honey Purple-gaped Honeyeaters on Kangaroo Island eater Lichenostomus cratitius (formerly Meli are, if anything, duller than mainland ones. phaga cratitia) was described as a distinct sub Condon (1951) says that the gape of this species by Mathews (1923-24); and Keast species is invariably yellow on Kangaroo Island (1961) mentions that six other species differ in instead of lilac, although he later comments a minor way from mainland populations and that lilac-gaped individuals do occur on the may merit subspecific status. -

Recent Honeyeater Migration in Southern Australia

June 2010 223 Recent Honeyeater Migration in Southern Australia BRYAN T HAYWOOD Abstract be seen moving through areas of south-eastern Australia during autumn (Ford 1983; Simpson & A conspicuous migration of honeyeaters particularly Day 1996). On occasions Fuscous Honeyeaters Yellow-faced Honeyeater, Lichenostomus chrysops, have been reported migrating in company with and White-naped Honeyeater, Melithreptus lunatus, Yellow-faced Honeyeaters, but only in small was observed in the SE of South Australia during numbers (Blakers et al., 1984). May and June 2007. A particularly significant day was 12 May 2007 when both species were Movements of honeyeaters throughout southern observed moving in mixed flocks in westerly and Australia are also predominantly up the east northerly directions in five different locations in the coast with birds moving from Victoria and New SE of South Australia. Migration of Yellow-faced South Wales (Hindwood 1956;Munro, Wiltschko Honeyeater and White-naped Honeyeater is not and Wiltschko 1993; Munro and Munro 1998) limited to following the coastline in the SE of South into southern Queensland. The timing and Australia, but also inland. During this migration direction at which these movements occur has period small numbers of Fuscous Honeyeater, L. been under considerable study with findings fuscus, were also observed. The broad-scale nature that birds (heading up the east coast) actually of these movements over the period April to June change from a north-easterly to north-westerly 2007 was indicated by records from south-western direction during this migration period. This Victoria, various locations in the SE of South change in direction is partly dictated by changes Australia, Adelaide and as far west as the Mid North in landscape features, but when Yellow-faced of SA. -

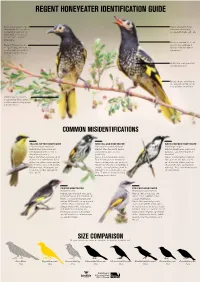

Regent Honeyeater Identification Guide

REGENT HONEYEATER IDENTIFICATION GUIDE Broad patch of bare warty Males call prominently, skin around the eye, which whereas females only is smaller in young birds occasionally make soft calls. and females. Best seen at close range or with binoculars. Plumage around the head Regent Honeyeaters are and neck is solid black 20-24 cm long, with females giving a slightly hooded smaller and having duller appearance. plumage than the males. Distinctive scalloped (not streaked) breast. Broad stripes of yellow in the wing when folded, and very prominent in flight. From below the tail is a bright yellow. From behind it’s black bordered by bright yellow feathers. COMMON MISIDENTIFICATIONS YELLOW-TUFTED HONEYEATER NEW HOLLAND HONEYEATER WHITE-CHEEKED HONEYEATER Lichenostomus melanops Phylidonyris novaehollandiae Phylidonyris niger Habitat: Box-Gum-Ironbark Habitat: Woodland with heathy Habitat: Heathlands, parks and woodlands and forest with a understorey, gardens and gardens, less commonly open shrubby understorey. parklands. woodland. Notes: Common, sedentary bird Notes: Often misidentified as a Notes: Similar to New Holland of temperate woodlands. Has a Regent Honeyeater; commonly Honeyeaters, but have a large distinctive yellow crown and ear seen in urban parks and gardens. patch of white feathers in their tuft in a black face, with a bright Distinctive white breast with black cheek and a dark eye (no white yellow throat. Underparts are streaks, several patches of white eye ring). Also have white breast plain dirty yellow, upperparts around the face, and a white eye streaked black. olive-green. ring. Tend to be in small, noisy and aggressive flocks. PAINTED HONEYEATER CRESCENT HONEYEATER Grantiella picta Phylidonyris pyrrhopterus Habitat: Box-Ironbark woodland, Habitat: Wetter habitats like particularly with fruiting mistletoe forest, dense woodland and Notes: A seasonal migrant, only coastal heathlands. -

Accepted Version

ACCEPTED VERSION Patrick L. Taggart Are blood haemoglobin concentrations a reliable indicator of parasitism and individual condition in New Holland honeyeaters (Phylidonyris novaehollandiae)? Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia, 2016; 140(1):17-27 © 2016 Royal Society of South Australia "This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia on 01 Mar 2016 available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03721426.2016.1151970 PERMISSIONS http://authorservices.taylorandfrancis.com/sharing-your-work/ Accepted Manuscript (AM) As a Taylor & Francis author, you can post your Accepted Manuscript (AM) on your personal website at any point after publication of your article (this includes posting to Facebook, Google groups, and LinkedIn, and linking from Twitter). To encourage citation of your work we recommend that you insert a link from your posted AM to the published article on Taylor & Francis Online with the following text: “This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in [JOURNAL TITLE] on [date of publication], available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/[Article DOI].” For example: “This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis Group in Africa Review on 17/04/2014, available online:http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/12345678.1234.123456. N.B. Using a real DOI will form a link to the Version of Record on Taylor & Francis Online. The AM is defined by the National Information Standards Organization as: “The version of a journal article that has been accepted for publication in a journal.” This means the version that has been through peer review and been accepted by a journal editor. -

Eastern Australia: October-November 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN AUSTRALIA: From Top to Bottom 23rd October – 11th November 2016 The bird of the trip, the very impressive POWERFUL OWL Tour Leader: Laurie Ross All photos in this report were taken by Laurie Ross/Tropical Birding. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 INTRODUCTION The Eastern Australia Set Departure Tour introduces a huge amount of new birds and families to the majority of the group. We started the tour in Cairns in Far North Queensland, where we found ourselves surrounded by multiple habitats from the tidal mudflats of the Cairns Esplanade, the Great Barrier Reef and its sandy cays, lush lowland and highland rainforests of the Atherton Tablelands, and we even made it to the edge of the Outback near Mount Carbine; the next leg of the tour took us south to Southeast Queensland where we spent time in temperate rainforests and wet sclerophyll forests within Lamington National Park. The third, and my favorite leg, of the tour took us down to New South Wales, where we birded a huge variety of new habitats from coastal heathland to rocky shorelines and temperate rainforests in Royal National Park, to the mallee and brigalow of Inland New South Wales. The fourth and final leg of the tour saw us on the beautiful island state of Tasmania, where we found all 13 “Tassie” endemics. We had a huge list of highlights, from finding a roosting Lesser Sooty Owl in Malanda; to finding two roosting Powerful Owls near Brisbane; to having an Albert’s Lyrebird walk out in front of us at O Reilly’s; to seeing the rare and endangered Regent Honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, and finding the endangered Swift Parrot on Bruny Island, in Tasmania. -

2015-Birds-Of-ML1.Pdf

FREE presents Birds of Mawson Lakes Linda Vining & MikeBIRDS Flynn of Mawson Lakes An online book available at www.mawsonlakesliving.info Republished as an ebook in 2015 First Published in 2013 Published by Mawson Lakes Living Magazine 43 Parkview Drive Mawson Lakes 5095 SOUTH AUSTRALIA Ph: +61 8 8260 7077 [email protected] www.mawsonlakesliving.info Photography and words by Mike Flynn Cover: New Holland Honeyeater. See page 22 for description © All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording or otherwise, without credit to the publisher. BIRDS inof MawsonMawson LakesLakes 3 Introduction What bird is that? Birdlife in Mawson Lakes is abundant and adds a wonderful dimension to our natural environment. Next time you go outside just listen to the sounds around you. The air is always filled with bird song. Birds bring great pleasure to the people of Mawson Lakes. There is nothing more arresting than a mother bird and her chicks swimming on the lakes in the spring. What a show stopper. The huge variety of birds provides magnificent opportunities for photographers. One of these is amateur photographer Mike Flynn who lives at Shearwater. Since coming to live at Mawson Lakes he has become an avid bird watcher and photographer. I often hear people ask: “What bird is that?” This book, brought to you by Mawson Lakes Living, is designed to answer this question by identifying birds commonly seen in Mawson Lakes and providing basic information on where to find them, what they eat and their distinctive features. -

Attracting Birds to Your Garden

Attracting Birds to your Garden What makes a good bird garden? Presence of tall trees Mature, indigenous trees provide hollows and other nesting sites, night-roosts, flowers for nectar, insects on leaves, under bark and buzzing around the flowers. Acacias (wattles), eucalypts, casuarinas, banksias or palms may be appropriate. Presence of middle and ground level shrubs A thick understorey layer of ferns, tall grasses, and shrubs from about ground level to two metres gives security to small birds such as thornbills, robins, scrubwrens and fairy-wrens. Grey fantail © A. Carew Permanent water supply Although the birdbath does not need to be fancy it needs to be kept filled, as birds will come to rely upon it. Each bath or pond must be carefully sited to allow small birds to dive quickly into nearby cover. Suburban proximity to a patch of natural bushland, within 3km The nearby bushland can help provide elements your garden cannot therefore increasing the diversity of habitat for birds in your area. A garden for the birds Below are a few examples of plants that attract birds to your garden; some provide shelter, some food, others both. Try to have a balance—too many of a particular type of plant will attract a limited range of birds. For example large, showy grevilleas tend to attract the more aggressive nectar-feeders like Red Wattlebird and Noisy Miner, reducing the opportunities for smaller birds. Please check the indigenous plants of your own area before making a selection. Shelter for small birds (scrubwrens, fairy-wrens, thornbills) Prickly dense shrubs – hakea, acacia, sweet bursaria, burgan, leptospermum. -

Grand Australia Part I: New South Wales & the Northern Territory September 28–October 14, 2019

GRAND AUSTRALIA PART I: NEW SOUTH WALES & THE NORTHERN TERRITORY SEPTEMBER 28–OCTOBER 14, 2019 A knock out Rose-crowned Fruit-Dove we found in Darwin perched out unusually brazenly. LEADERS: DION HOBCROFT AND JANENE LUFF LIST COMPILED BY: DION HOBCROFT VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM Our Australia tours have become so popular that we ran two VENT departures this year around the continent. The first was led by great birding friend and outstanding leader Max Breckenridge, well assisted by Barry Zimmer, one of our most highly regarded leaders. Janene and I led the second departure starting a week later. As usual, we started in Sydney at a comfortable hotel close to city attractions like the Opera House, Botanic Gardens, Art Gallery, and various museums. This included some good birding sites like Sydney Olympic Park some five miles west of the city. This young male Superb Lyrebird came walking past us in rainforest at Royal National Park. Our tour began with great cool weather, and in the park we were soon amongst the attractions with nesting Tawny Frogmouth a good start. There were plenty of waterbirds including Black Swan, Chestnut Teal, Hardhead, Australasian Darter, four species of cormorants, and three species of large rails (swamphen, moorhen, and coot). On the tidal lagoon, good numbers of Red-necked Avocets mingled about with a small flock of recently arrived migrant Sharp-tailed Sandpipers, while a dapper pair of adult Red-kneed Dotterels was very handy. Participants were somewhat “gobsmacked” by colorful Galahs, Rainbow Lorikeets, raucous Sulphur-crested Cockatoos, and their smaller cousin the Little Corella. -

Avian Population Changes in a Developing Urban Area in Western

Corella,2002' 26(3): 79-84 AVIANPOPULATION CHANGES IN A DEVELOPINGURBAN AREA IN WESTERNAUSTRALIA OVER AN EIGHTEENYEAR PERIOD VICTORW. SMITH I KarrakatlaRoad. Goode Beach,Albany. western Australia 6330 Received:27 Nownbet 2000 Annual capture and recapture rates of a number o1 bird species obtained over an eighteen year period in an area cleared lor urbanization,have shown changes in populationswhich are consideredrelated to developmentin the area. The increase in thg number ol honeyeatersin particular,implies they havo benelitted from the prolilerationot nectar-producingnative plants in some residentialgardens. Other discrete changes ln the avian oooLllationare also described INTRODUCTION meant that much of lhe original vegetation was destroyed As water conservation was a priority in lhe area, quick-growing native shrubs In 1982, a bird-banding project was commenced to alld trecs which do not require much water werc oflen selected gathermorphometric data from avian speciesin the south for residential gardens. The bare or sparse nature of newly gardens years early of WesternAustralia. The continuationof this project to developcd blocks, a feature of some for several on, gave way !o tallcr shrubs and trees (up to l0 m in heigh0, in 2000 has provided unforeseen, though not entirely a relatively short time. Within two !o four years afte. completion unexpected,information on local populationtrends over of each rcsidence, several gardens grew flourishing slands of planls time. and small trees native to Western Australia. This provided on_8oing nectar sources throughout the year with. for e\amplc, CalListennn, Large areas of coastal Australia have undergone Grcvillea, Kunzea and MelaLeuca species flowering during the transition from remnant bushland to suburban winter and early summer and El.cdllptrr species flowering during development.Urbanization brings mixed blessingsfor the summer and autumn Furthermore, water was made frcely avrrlable ro lhe bird, b) mdnJ rcsident' birds.Clearing remnant bushland removes food resources, shelterand breedingsites. -

Fauna Assessment

Fauna Assessment South Capel May 2018 V4 On behalf of: Iluka Resources Limited 140 St Georges Terrace PERTH WA 6000 Prepared by: Greg Harewood Zoologist PO Box 755 BUNBURY WA 6231 M: 0402 141 197 E: [email protected] FAUNA ASSESSMENT – SOUTH CAPEL –– MAY 2018 – V4 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY 1. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 1 2. SCOPE OF WORKS ................................................................................................ 1 3. METHODS ............................................................................................................... 2 3.1 POTENTIAL FAUNA INVENTORY - LITERATURE REVIEW ................................. 2 3.1.1 Database Searches ....................................................................................... 2 3.1.2 Previous Fauna Surveys in the Area ............................................................. 2 3.1.3 Fauna of Conservation Significance .............................................................. 4 3.1.4 Invertebrate Fauna of Conservation Significance .......................................... 5 3.1.5 Likelihood of Occurrence – Fauna of Conservation Significance .................. 5 3.1.6 Taxonomy and Nomenclature ........................................................................ 6 3.2 SITE SURVEYS ....................................................................................................... 7 3.2.1 Fauna Habitat Assessment ........................................................................... -

Sex Determination by Morphology in New Holland Honeyeaters, Phylidonyris Novaehollandiae: Contrasting Two Popular Techniques Across Regions STEVEN MYERS, DAVID C

December 2012 1 Sex determination by morphology in New Holland Honeyeaters, Phylidonyris novaehollandiae: contrasting two popular techniques across regions SteVeN MYeRS, dAVid C. PAtoN ANd SoNiA KLeiNdoRFeR Abstract dichromatism or dimorphism. In such cases, Sex determination of individuals is often required sex may be determined non-invasively using for ecological and behavioural studies but is difficult behavioural cues (Baeyens 1981), or by the to carry out in the field for species that are only presence of a brood patch on incubating females slightly dimorphic. To address this issue, researchers or a protruding cloaca in males. However, may use a variety of methods that rely solely on these approaches are usually only possible with morphological measurements for sex determination. sexually active individuals during the breeding There are two main groups of morphological methods; season. (1) based on discriminant analysis, and (2) based on resolving mixed-modal distributions. Here, we The difficulties of sex determination for species use one method from each of the two groups to sex with only slight sexual dimorphism may the slightly dimorphic New Holland Honeyeater, be overcome by examining morphological Phylidonyris novaehollandiae, in South Australia, measurements. Two techniques that can be used and we compare results of the two methods in relation to determine sex based solely on morphological to a genetic standard. We found that performance of measurements are cited above all others: (1) both methods was comparable, but varied between more traditional methods based on resolving populations. We also found regional differences in the mixed-modal distributions (Disney 1966; Rogers best discriminating variables for morphological sex et al. -

The Breeding Biology of the Dusky Honeyeater Myzomela Obscura in the Northern Territory, and the Importance of Nectar in the Diet of Nestling Honeyeaters

97 AUSTRALIAN FIELD ORNITHOLOGY 2011, 28, 97–113 The Breeding Biology of the Dusky Honeyeater Myzomela obscura in the Northern Territory, and the Importance of Nectar in the Diet of Nestling Honeyeaters RICHARD A. NOSKE1 and ASHLEY J. CARLSON2 1Research Institute for the Environment and Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, Northern Territory 0909 (Email: [email protected]) 2P.O. Box 4074, Forster, New South Wales 2428 (Email: [email protected]) Summary The breeding biology of the Dusky Honeyeater Myzomela obscura is poorly known, despite the species’ wide distribution and use of a broad range of habitats. In the Northern Territory, breeding was recorded in all months, but just over 50% of estimated laying dates were in April and May, corresponding with the transition from the wet to the dry season. In Darwin, nests were placed 1.0 to 9.0 m above the ground in a variety of trees or tall shrubs, including exotics. The size of clutches or broods never exceeded two (n = 9). At two closely observed nests, the incubation period was 12.4 and 12.75 days, similar to another myzomeline honeyeater. Nest-attentiveness was ~65% over 2 days at one nest, similar to the few temperate-zone Australian honeyeaters for which such data are available. The nestling period at the only successful nest that we observed was 14.3 ± 0.7 days, consistent with slightly smaller species in other honeyeater genera. Unlike most honeyeater species, nestling Dusky Honeyeaters hatched with much down. Diurnal brooding represented 20–28% of the presumed female’s time during the first 4 days after hatching, but had ceased by Day 6, earlier than in temperate-zone honeyeater species.