Accepted Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A 'Slow Pace of Life' in Australian Old-Endemic Passerine Birds Is Not Accompanied by Low Basal Metabolic Rates

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers: part A Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health 1-1-2016 A 'slow pace of life' in Australian old-endemic passerine birds is not accompanied by low basal metabolic rates Claus Bech University of Wollongong Mark A. Chappell University of Wollongong, [email protected] Lee B. Astheimer University of Wollongong, [email protected] Gustavo A. Londoño Universidad Icesi William A. Buttemer University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/smhpapers Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Bech, Claus; Chappell, Mark A.; Astheimer, Lee B.; Londoño, Gustavo A.; and Buttemer, William A., "A 'slow pace of life' in Australian old-endemic passerine birds is not accompanied by low basal metabolic rates" (2016). Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers: part A. 3841. https://ro.uow.edu.au/smhpapers/3841 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] A 'slow pace of life' in Australian old-endemic passerine birds is not accompanied by low basal metabolic rates Abstract Life history theory suggests that species experiencing high extrinsic mortality rates allocate more resources toward reproduction relative to self-maintenance and reach maturity earlier ('fast pace of life') than those having greater life expectancy and reproducing at a lower rate ('slow pace of life'). Among birds, many studies have shown that tropical species have a slower pace of life than temperate-breeding species. -

THE HONEYEATERS of KANGAROO ISLAND HUGH FOB,D Accepted August

134 SOUTH AUsTRALIAN ORNITHOLOGIST, 21 THE HONEYEATERS OF KANGAROO ISLAND HUGH FOB,D Accepted August. 1976 Kangaroo Island is the third largest of Aus In the present paper I discuss morphological tralia's islands (4,500 sq. km) and has been and ecological differences between populations separated from the neighbouring Fleurieu of several species of honeyeaters from Kangaroo Peninsula for 10,000 years (Abbott 1973). A Island and the Fleurieu Peninsula respectively, mere 14 km separates island from mainland; and speculate on how these differences origin but the island has a distinct avifauna and lacks ated. many of the mainland species. This paucity of DIFFERENCES IN PLUMAGE species has been attributed to extinction after The Kangaroo Island population of Purple isolation and failure to recolonise (Abbott gaped Honeyeater was described as larger and 1974, 1976), and to lack of suitable habitat brighter than the mainland population by (Ford and Paton 1975). Mathews (1923-4). Brightness of plumage is a Nine species of honeyeaters are resident on very subjective characteristic, and in my opinion Kangaroo Island. The Purple-gaped Honey Purple-gaped Honeyeaters on Kangaroo Island eater Lichenostomus cratitius (formerly Meli are, if anything, duller than mainland ones. phaga cratitia) was described as a distinct sub Condon (1951) says that the gape of this species by Mathews (1923-24); and Keast species is invariably yellow on Kangaroo Island (1961) mentions that six other species differ in instead of lilac, although he later comments a minor way from mainland populations and that lilac-gaped individuals do occur on the may merit subspecific status. -

DRAFT Biodiversity Action Plan 2021 - 2026

DRAFT Biodiversity Action Plan 2021 - 2026 Prepared by: Infrastructure Services & Planning and Ecology Australia Contents Acknowledgments 4 A Vision for the Future 5 Introduction 6 Summary of state and extent of biodiversity in Greater Dandenong 7 Study area 7 Flora and fauna 9 Existing landscape habitat types 10 Key threats to local biodiversity values 12 Habitat assessments 15 Habitat connectivity for icon species 16 Community consultation and engagement 18 Biodiversity legislation considerations 20 Council strategies 22 Actions 23 Protection and enhancement of existing biodiversity values 24 Improving knowledge of biodiversity values 26 Facilitating and encouraging biodiversity conservation and enhancement on private land 27 Managing threatening processes 28 Community engagement and education 30 References 32 Tables Table 1 Summary of most common reasons why biodiversity is considered important from online survey and examples of comments provided 19 Table 2 Commonwealth and Victorian biodiversity legislation 20 Plates Plate 1 City of Greater Dandenong LGA and municipality study area, including surrounding areas of biodiversity significance. 8 Plate 2 Potential connectivity sites within Greater Dandenong for all five icon species 17 DRAFT City of Greater Dandenong Biodiversity Action Plan 2021 – 2026 ii Appendices Appendix 1 Vegetation coverage across the City of Greater Dandenong pre 1750 (left) and today (right). 34 Appendix 2 Fauna species listed as threatened under the EPBC Act 1999 (DAWE 2020), FFG Act 1988 (DELWP 2019b) or the Victorian Threatened Species Advisory List recorded within the City of Greater Dandenong municipality ....................................................................................................... 35 Appendix 3 Flora species listed as threatened under the EPBC Act 1999 (DAWE 2020), FFG Act 1988 (DELWP 2019b) or the Victorian Threatened Species Advisory List recorded within the City of Greater Dandenong municipality ...................................................................................................... -

Bush Birds Making Your Place Their Place Too

BUSH BIRDS MAKING YOUR PLACE THEIR PLACE TOO This fact sheet explains which bush birds may be present or absent from your place and what you can do to encourage a greater diversity to live with you. The drier, settled areas of southern Tasmania, and whistlers. Some, like Pink Robin and Scrubtit, compared to other places, still have much of their prefer wet forest and others, such as Forty- original bush. In many instances the clearing for spotted Pardalote are rarely seen outside their agriculture and urban development has produced preferred specialist habitat. a mosaic of habitats including highly modified The Yellow-throated Honeyeater needs bush with Some species live in the same bush all year, treeless paddocks through to fully vegetated hills, good structure, as it forages high in trees but nests whilst others migrate in the late autumn to in which many species of birds still thrive. But bird in shrubs close to the ground. increase their foraging range, descend in species begin to decline or will be absent where altitude or cross Bass Strait to spend their intact patches of bush are lost or if this mosaic winter on mainland Australia. Bush habitat also BUSH BIRDS’ HOMES becomes too highly modified. supports birds of prey, water birds in creeks and Just like us, birds have three basic needs: About 60 species of birds live within the bush of wetlands, and a small number of other species 1. Their preferred food. southern Tasmania. Common groups of species using heaths or grasslands on the forest fringe. include honeyeaters, parrots, robins, pardalotes 2. -

Recent Honeyeater Migration in Southern Australia

June 2010 223 Recent Honeyeater Migration in Southern Australia BRYAN T HAYWOOD Abstract be seen moving through areas of south-eastern Australia during autumn (Ford 1983; Simpson & A conspicuous migration of honeyeaters particularly Day 1996). On occasions Fuscous Honeyeaters Yellow-faced Honeyeater, Lichenostomus chrysops, have been reported migrating in company with and White-naped Honeyeater, Melithreptus lunatus, Yellow-faced Honeyeaters, but only in small was observed in the SE of South Australia during numbers (Blakers et al., 1984). May and June 2007. A particularly significant day was 12 May 2007 when both species were Movements of honeyeaters throughout southern observed moving in mixed flocks in westerly and Australia are also predominantly up the east northerly directions in five different locations in the coast with birds moving from Victoria and New SE of South Australia. Migration of Yellow-faced South Wales (Hindwood 1956;Munro, Wiltschko Honeyeater and White-naped Honeyeater is not and Wiltschko 1993; Munro and Munro 1998) limited to following the coastline in the SE of South into southern Queensland. The timing and Australia, but also inland. During this migration direction at which these movements occur has period small numbers of Fuscous Honeyeater, L. been under considerable study with findings fuscus, were also observed. The broad-scale nature that birds (heading up the east coast) actually of these movements over the period April to June change from a north-easterly to north-westerly 2007 was indicated by records from south-western direction during this migration period. This Victoria, various locations in the SE of South change in direction is partly dictated by changes Australia, Adelaide and as far west as the Mid North in landscape features, but when Yellow-faced of SA. -

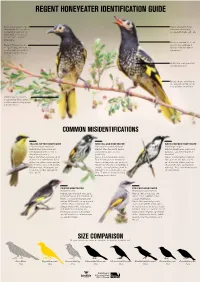

Regent Honeyeater Identification Guide

REGENT HONEYEATER IDENTIFICATION GUIDE Broad patch of bare warty Males call prominently, skin around the eye, which whereas females only is smaller in young birds occasionally make soft calls. and females. Best seen at close range or with binoculars. Plumage around the head Regent Honeyeaters are and neck is solid black 20-24 cm long, with females giving a slightly hooded smaller and having duller appearance. plumage than the males. Distinctive scalloped (not streaked) breast. Broad stripes of yellow in the wing when folded, and very prominent in flight. From below the tail is a bright yellow. From behind it’s black bordered by bright yellow feathers. COMMON MISIDENTIFICATIONS YELLOW-TUFTED HONEYEATER NEW HOLLAND HONEYEATER WHITE-CHEEKED HONEYEATER Lichenostomus melanops Phylidonyris novaehollandiae Phylidonyris niger Habitat: Box-Gum-Ironbark Habitat: Woodland with heathy Habitat: Heathlands, parks and woodlands and forest with a understorey, gardens and gardens, less commonly open shrubby understorey. parklands. woodland. Notes: Common, sedentary bird Notes: Often misidentified as a Notes: Similar to New Holland of temperate woodlands. Has a Regent Honeyeater; commonly Honeyeaters, but have a large distinctive yellow crown and ear seen in urban parks and gardens. patch of white feathers in their tuft in a black face, with a bright Distinctive white breast with black cheek and a dark eye (no white yellow throat. Underparts are streaks, several patches of white eye ring). Also have white breast plain dirty yellow, upperparts around the face, and a white eye streaked black. olive-green. ring. Tend to be in small, noisy and aggressive flocks. PAINTED HONEYEATER CRESCENT HONEYEATER Grantiella picta Phylidonyris pyrrhopterus Habitat: Box-Ironbark woodland, Habitat: Wetter habitats like particularly with fruiting mistletoe forest, dense woodland and Notes: A seasonal migrant, only coastal heathlands. -

Download Preprint

A continental measure of urbanness predicts avian response to local urbanization Corey T. Callaghan*1 (0000-0003-0415-2709), Richard E. Major1,2 (0000-0002-1334-9864), William K. Cornwell1,3 (0000-0003-4080-4073), Alistair G. B. Poore3 (0000-0002-3560- 3659), John H. Wilshire1, Mitchell B. Lyons1 (0000-0003-3960-3522) 1Centre for Ecosystem Science; School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences; UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia 2Australian Museum Research Institute, Australian Museum, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 3Evolution and Ecology Research Centre; School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences; UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia *Corresponding author: [email protected] NOTE: This is a pre-print, and the final published version of this manuscript can be found here: https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.04863 Acknowledgements Funding for this work was provided by the Australian Wildlife Society. Mark Ley, Simon Gorta, and Max Breckenridge were instrumental in conducting surveys in the Blue Mountains. We also are grateful to the numerous volunteers who submit their data to eBird, and the dedicated team of reviewers who ensure the quality of the database. We thank the associate editor and two anonymous reviewers for comments that improved this manuscript. Author contributions CTC, WKC, JHW, and REM conceptualized the data processing to assign urban scores. CTC, MBL, and REM designed the study. CTC performed the data analysis with insight from WKC and AGBP. All authors contributed to drafting and editing the manuscript. Data accessibility Code and data necessary to reproduce these analyses have been uploaded as supplementary material alongside this manuscript, and will be made available as a permanently archived Zenodo repository upon acceptance of the manuscript. -

Eastern Australia: October-November 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN AUSTRALIA: From Top to Bottom 23rd October – 11th November 2016 The bird of the trip, the very impressive POWERFUL OWL Tour Leader: Laurie Ross All photos in this report were taken by Laurie Ross/Tropical Birding. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 INTRODUCTION The Eastern Australia Set Departure Tour introduces a huge amount of new birds and families to the majority of the group. We started the tour in Cairns in Far North Queensland, where we found ourselves surrounded by multiple habitats from the tidal mudflats of the Cairns Esplanade, the Great Barrier Reef and its sandy cays, lush lowland and highland rainforests of the Atherton Tablelands, and we even made it to the edge of the Outback near Mount Carbine; the next leg of the tour took us south to Southeast Queensland where we spent time in temperate rainforests and wet sclerophyll forests within Lamington National Park. The third, and my favorite leg, of the tour took us down to New South Wales, where we birded a huge variety of new habitats from coastal heathland to rocky shorelines and temperate rainforests in Royal National Park, to the mallee and brigalow of Inland New South Wales. The fourth and final leg of the tour saw us on the beautiful island state of Tasmania, where we found all 13 “Tassie” endemics. We had a huge list of highlights, from finding a roosting Lesser Sooty Owl in Malanda; to finding two roosting Powerful Owls near Brisbane; to having an Albert’s Lyrebird walk out in front of us at O Reilly’s; to seeing the rare and endangered Regent Honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, and finding the endangered Swift Parrot on Bruny Island, in Tasmania. -

December 2016 Vol

Castlemaine Naturalist December 2016 Vol. 41.11 #449 Monthly newsletter of the Castlemaine Field Naturalists Club Inc. Powerful Owl chick - photo Noel Young Moths of Victoria – and Castlemaine CFNC members were fortunate to have Marilyn Hewish as guest speaker at the Club’s November meeting. Marilyn is a distinguished naturalist, who received the Australian Natural History Medallion in 2013 for her decades of work on Australian birds and her more recent contributions to studies of the moths of Victoria. She told us how she had become a “moth addict” and that most of the commonly stated ways to distinguish moths and butterflies are myths – some moths are active during daylight, many are highly coloured (not “brown and boring”), some have clubbed antennae. The technical difference is in the way the forewings and hindwings are linked – needing microscopic examination! Moths and their caterpillars play a major ecological role, for example as a significant food source for birds, bats, reptiles, small mammals and larger invertebrates. Some caterpillars feed on leaf litter, thus recycling nutrients and reducing the intensity of fires. Some day-flying moths pollinate flowers. Though butterflies are more familiar to most naturalists, they are far outnumbered by moth species in Australia: about 400 species of butterflies and more than 20,000 moths (the exact figure is not known). The studies of Victorian moths are in very early stages compared to our knowledge of Australian birds. Marilyn and Dean are frequently in the field – at night (even when cold and wet), surveying moths at sites across Victoria. They often record large extensions in distributions, species not previously known from the state, and even species new to science. -

2015-Birds-Of-ML1.Pdf

FREE presents Birds of Mawson Lakes Linda Vining & MikeBIRDS Flynn of Mawson Lakes An online book available at www.mawsonlakesliving.info Republished as an ebook in 2015 First Published in 2013 Published by Mawson Lakes Living Magazine 43 Parkview Drive Mawson Lakes 5095 SOUTH AUSTRALIA Ph: +61 8 8260 7077 [email protected] www.mawsonlakesliving.info Photography and words by Mike Flynn Cover: New Holland Honeyeater. See page 22 for description © All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording or otherwise, without credit to the publisher. BIRDS inof MawsonMawson LakesLakes 3 Introduction What bird is that? Birdlife in Mawson Lakes is abundant and adds a wonderful dimension to our natural environment. Next time you go outside just listen to the sounds around you. The air is always filled with bird song. Birds bring great pleasure to the people of Mawson Lakes. There is nothing more arresting than a mother bird and her chicks swimming on the lakes in the spring. What a show stopper. The huge variety of birds provides magnificent opportunities for photographers. One of these is amateur photographer Mike Flynn who lives at Shearwater. Since coming to live at Mawson Lakes he has become an avid bird watcher and photographer. I often hear people ask: “What bird is that?” This book, brought to you by Mawson Lakes Living, is designed to answer this question by identifying birds commonly seen in Mawson Lakes and providing basic information on where to find them, what they eat and their distinctive features. -

Attracting Birds to Your Garden

Attracting Birds to your Garden What makes a good bird garden? Presence of tall trees Mature, indigenous trees provide hollows and other nesting sites, night-roosts, flowers for nectar, insects on leaves, under bark and buzzing around the flowers. Acacias (wattles), eucalypts, casuarinas, banksias or palms may be appropriate. Presence of middle and ground level shrubs A thick understorey layer of ferns, tall grasses, and shrubs from about ground level to two metres gives security to small birds such as thornbills, robins, scrubwrens and fairy-wrens. Grey fantail © A. Carew Permanent water supply Although the birdbath does not need to be fancy it needs to be kept filled, as birds will come to rely upon it. Each bath or pond must be carefully sited to allow small birds to dive quickly into nearby cover. Suburban proximity to a patch of natural bushland, within 3km The nearby bushland can help provide elements your garden cannot therefore increasing the diversity of habitat for birds in your area. A garden for the birds Below are a few examples of plants that attract birds to your garden; some provide shelter, some food, others both. Try to have a balance—too many of a particular type of plant will attract a limited range of birds. For example large, showy grevilleas tend to attract the more aggressive nectar-feeders like Red Wattlebird and Noisy Miner, reducing the opportunities for smaller birds. Please check the indigenous plants of your own area before making a selection. Shelter for small birds (scrubwrens, fairy-wrens, thornbills) Prickly dense shrubs – hakea, acacia, sweet bursaria, burgan, leptospermum. -

Grand Australia Part I: New South Wales & the Northern Territory September 28–October 14, 2019

GRAND AUSTRALIA PART I: NEW SOUTH WALES & THE NORTHERN TERRITORY SEPTEMBER 28–OCTOBER 14, 2019 A knock out Rose-crowned Fruit-Dove we found in Darwin perched out unusually brazenly. LEADERS: DION HOBCROFT AND JANENE LUFF LIST COMPILED BY: DION HOBCROFT VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM Our Australia tours have become so popular that we ran two VENT departures this year around the continent. The first was led by great birding friend and outstanding leader Max Breckenridge, well assisted by Barry Zimmer, one of our most highly regarded leaders. Janene and I led the second departure starting a week later. As usual, we started in Sydney at a comfortable hotel close to city attractions like the Opera House, Botanic Gardens, Art Gallery, and various museums. This included some good birding sites like Sydney Olympic Park some five miles west of the city. This young male Superb Lyrebird came walking past us in rainforest at Royal National Park. Our tour began with great cool weather, and in the park we were soon amongst the attractions with nesting Tawny Frogmouth a good start. There were plenty of waterbirds including Black Swan, Chestnut Teal, Hardhead, Australasian Darter, four species of cormorants, and three species of large rails (swamphen, moorhen, and coot). On the tidal lagoon, good numbers of Red-necked Avocets mingled about with a small flock of recently arrived migrant Sharp-tailed Sandpipers, while a dapper pair of adult Red-kneed Dotterels was very handy. Participants were somewhat “gobsmacked” by colorful Galahs, Rainbow Lorikeets, raucous Sulphur-crested Cockatoos, and their smaller cousin the Little Corella.