Honey Possum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Encouraging Possums

Encouraging Possums Keywords: possums, mammals, habitat, management, nest boxes Location: southwest Author: Emma Bramwell Possums are delightful and appealing creatures, with THE SEVEN SPECIES their soft downy fur and large innocent eyes. Some may be as small as a mouse while others are the size of a domestic • Honeypossum Tarsipes rostratus cat. The honey possum is the smallest of the Western The western ringtail and common brushtail possums are Australian possums, and is endemic to (occurring only in) two of the most commonly seen native animals around urban the lower southwest, in heaths with a rich diversity of areas in the southwest of Western Australia. The common nectar-producing plants. brushtail possum in particular has adapted to urban Mainly nocturnal, the honey possum sleeps during the development, and readily takes up residence in human day in hollow stems or abandoned bird nests, emerging at dwellings. With careful planning and management, people night to feed on the nectar and pollen that exclusively make can live harmoniously with these creatures and enjoy the up its diet, probing flowers with its long, pointed snout and close proximity of wildlife. brush-tipped tongue. In colder weather the honey possum becomes torpid (semi-hibernates). The honey possum has no obvious breeding season. WHAT IS A POSSUM? Most young are produced when pollen and nectar are most abundant, and females usually raise two or three young at a A number of small to medium-sized, tree-climbing time. Australian marsupial species have been given the common Provided large areas of habitat are retained, the honey name of possum. -

A 'Slow Pace of Life' in Australian Old-Endemic Passerine Birds Is Not Accompanied by Low Basal Metabolic Rates

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers: part A Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health 1-1-2016 A 'slow pace of life' in Australian old-endemic passerine birds is not accompanied by low basal metabolic rates Claus Bech University of Wollongong Mark A. Chappell University of Wollongong, [email protected] Lee B. Astheimer University of Wollongong, [email protected] Gustavo A. Londoño Universidad Icesi William A. Buttemer University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/smhpapers Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Bech, Claus; Chappell, Mark A.; Astheimer, Lee B.; Londoño, Gustavo A.; and Buttemer, William A., "A 'slow pace of life' in Australian old-endemic passerine birds is not accompanied by low basal metabolic rates" (2016). Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers: part A. 3841. https://ro.uow.edu.au/smhpapers/3841 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] A 'slow pace of life' in Australian old-endemic passerine birds is not accompanied by low basal metabolic rates Abstract Life history theory suggests that species experiencing high extrinsic mortality rates allocate more resources toward reproduction relative to self-maintenance and reach maturity earlier ('fast pace of life') than those having greater life expectancy and reproducing at a lower rate ('slow pace of life'). Among birds, many studies have shown that tropical species have a slower pace of life than temperate-breeding species. -

Bird Species List for Mount Majura

Bird Species List for Mount Majura This list of bird species is based on entries in the database of the Canberra Ornithologists Group (COG). The common English names are drawn from: Christidis, L. & Boles, W.E. (1994) The Taxonomy and Species of Birds of Australia and its Territories. Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union Monograph 2, RAOU, Melbourne. (1) List in taxonomic order Stubble Quail Southern Boobook Australian Wood Duck Tawny Frogmouth Pacific Black Duck White-throated Needletail Little Black Cormorant Laughing Kookaburra White-faced Heron Sacred Kingfisher Nankeen Night Heron Dollarbird Brown Goshawk White-throated Treecreeper Collared Sparrowhawk Superb Fairy-wren Wedge-tailed Eagle Spotted Pardalote Little Eagle Striated Pardalote Australian Hobby White-browed Scrubwren Peregrine Falcon Chestnut-rumped Heathwren Brown Falcon Speckled Warbler Nankeen Kestrel Weebill Painted Button-quail Western Gerygone Masked Lapwing White-throated Gerygone Rock Dove Brown Thornbill Common Bronzewing Buff-rumped Thornbill Crested Pigeon Yellow-rumped Thornbill Glossy Black-Cockatoo Yellow Thornbill Yellow-tailed Black-Cockatoo Striated Thornbill Gang-gang Cockatoo Southern Whiteface Galah Red Wattlebird Sulphur-crested Cockatoo Noisy Friarbird Little Lorikeet Regent Honeyeater Australian King-Parrot Noisy Miner Crimson Rosella Yellow-faced Honeyeater Eastern Rosella White-eared Honeyeater Red-rumped Parrot Fuscous Honeyeater Swift Parrot White-plumed Honeyeater Pallid Cuckoo Brown-headed Honeyeater Brush Cuckoo White-naped Honeyeater Fan-tailed -

DRAFT Biodiversity Action Plan 2021 - 2026

DRAFT Biodiversity Action Plan 2021 - 2026 Prepared by: Infrastructure Services & Planning and Ecology Australia Contents Acknowledgments 4 A Vision for the Future 5 Introduction 6 Summary of state and extent of biodiversity in Greater Dandenong 7 Study area 7 Flora and fauna 9 Existing landscape habitat types 10 Key threats to local biodiversity values 12 Habitat assessments 15 Habitat connectivity for icon species 16 Community consultation and engagement 18 Biodiversity legislation considerations 20 Council strategies 22 Actions 23 Protection and enhancement of existing biodiversity values 24 Improving knowledge of biodiversity values 26 Facilitating and encouraging biodiversity conservation and enhancement on private land 27 Managing threatening processes 28 Community engagement and education 30 References 32 Tables Table 1 Summary of most common reasons why biodiversity is considered important from online survey and examples of comments provided 19 Table 2 Commonwealth and Victorian biodiversity legislation 20 Plates Plate 1 City of Greater Dandenong LGA and municipality study area, including surrounding areas of biodiversity significance. 8 Plate 2 Potential connectivity sites within Greater Dandenong for all five icon species 17 DRAFT City of Greater Dandenong Biodiversity Action Plan 2021 – 2026 ii Appendices Appendix 1 Vegetation coverage across the City of Greater Dandenong pre 1750 (left) and today (right). 34 Appendix 2 Fauna species listed as threatened under the EPBC Act 1999 (DAWE 2020), FFG Act 1988 (DELWP 2019b) or the Victorian Threatened Species Advisory List recorded within the City of Greater Dandenong municipality ....................................................................................................... 35 Appendix 3 Flora species listed as threatened under the EPBC Act 1999 (DAWE 2020), FFG Act 1988 (DELWP 2019b) or the Victorian Threatened Species Advisory List recorded within the City of Greater Dandenong municipality ...................................................................................................... -

Yarra's Topography Is Gently Undulating, Which Is Characteristic of the Western Basalt Plains

Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 Acknowledgement of country ............................................................................................................................ 3 Message from the Mayor ................................................................................................................................... 4 Vision and goals ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 Nature in Yarra .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Policy and strategy relevant to natural values ................................................................................................. 27 Legislative context ........................................................................................................................................... 27 What does Yarra do to support nature? .......................................................................................................... 28 Opportunities and challenges for nature ......................................................................................................... -

Recent Honeyeater Migration in Southern Australia

June 2010 223 Recent Honeyeater Migration in Southern Australia BRYAN T HAYWOOD Abstract be seen moving through areas of south-eastern Australia during autumn (Ford 1983; Simpson & A conspicuous migration of honeyeaters particularly Day 1996). On occasions Fuscous Honeyeaters Yellow-faced Honeyeater, Lichenostomus chrysops, have been reported migrating in company with and White-naped Honeyeater, Melithreptus lunatus, Yellow-faced Honeyeaters, but only in small was observed in the SE of South Australia during numbers (Blakers et al., 1984). May and June 2007. A particularly significant day was 12 May 2007 when both species were Movements of honeyeaters throughout southern observed moving in mixed flocks in westerly and Australia are also predominantly up the east northerly directions in five different locations in the coast with birds moving from Victoria and New SE of South Australia. Migration of Yellow-faced South Wales (Hindwood 1956;Munro, Wiltschko Honeyeater and White-naped Honeyeater is not and Wiltschko 1993; Munro and Munro 1998) limited to following the coastline in the SE of South into southern Queensland. The timing and Australia, but also inland. During this migration direction at which these movements occur has period small numbers of Fuscous Honeyeater, L. been under considerable study with findings fuscus, were also observed. The broad-scale nature that birds (heading up the east coast) actually of these movements over the period April to June change from a north-easterly to north-westerly 2007 was indicated by records from south-western direction during this migration period. This Victoria, various locations in the SE of South change in direction is partly dictated by changes Australia, Adelaide and as far west as the Mid North in landscape features, but when Yellow-faced of SA. -

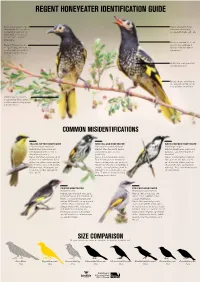

Regent Honeyeater Identification Guide

REGENT HONEYEATER IDENTIFICATION GUIDE Broad patch of bare warty Males call prominently, skin around the eye, which whereas females only is smaller in young birds occasionally make soft calls. and females. Best seen at close range or with binoculars. Plumage around the head Regent Honeyeaters are and neck is solid black 20-24 cm long, with females giving a slightly hooded smaller and having duller appearance. plumage than the males. Distinctive scalloped (not streaked) breast. Broad stripes of yellow in the wing when folded, and very prominent in flight. From below the tail is a bright yellow. From behind it’s black bordered by bright yellow feathers. COMMON MISIDENTIFICATIONS YELLOW-TUFTED HONEYEATER NEW HOLLAND HONEYEATER WHITE-CHEEKED HONEYEATER Lichenostomus melanops Phylidonyris novaehollandiae Phylidonyris niger Habitat: Box-Gum-Ironbark Habitat: Woodland with heathy Habitat: Heathlands, parks and woodlands and forest with a understorey, gardens and gardens, less commonly open shrubby understorey. parklands. woodland. Notes: Common, sedentary bird Notes: Often misidentified as a Notes: Similar to New Holland of temperate woodlands. Has a Regent Honeyeater; commonly Honeyeaters, but have a large distinctive yellow crown and ear seen in urban parks and gardens. patch of white feathers in their tuft in a black face, with a bright Distinctive white breast with black cheek and a dark eye (no white yellow throat. Underparts are streaks, several patches of white eye ring). Also have white breast plain dirty yellow, upperparts around the face, and a white eye streaked black. olive-green. ring. Tend to be in small, noisy and aggressive flocks. PAINTED HONEYEATER CRESCENT HONEYEATER Grantiella picta Phylidonyris pyrrhopterus Habitat: Box-Ironbark woodland, Habitat: Wetter habitats like particularly with fruiting mistletoe forest, dense woodland and Notes: A seasonal migrant, only coastal heathlands. -

Download Preprint

A continental measure of urbanness predicts avian response to local urbanization Corey T. Callaghan*1 (0000-0003-0415-2709), Richard E. Major1,2 (0000-0002-1334-9864), William K. Cornwell1,3 (0000-0003-4080-4073), Alistair G. B. Poore3 (0000-0002-3560- 3659), John H. Wilshire1, Mitchell B. Lyons1 (0000-0003-3960-3522) 1Centre for Ecosystem Science; School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences; UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia 2Australian Museum Research Institute, Australian Museum, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 3Evolution and Ecology Research Centre; School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences; UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia *Corresponding author: [email protected] NOTE: This is a pre-print, and the final published version of this manuscript can be found here: https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.04863 Acknowledgements Funding for this work was provided by the Australian Wildlife Society. Mark Ley, Simon Gorta, and Max Breckenridge were instrumental in conducting surveys in the Blue Mountains. We also are grateful to the numerous volunteers who submit their data to eBird, and the dedicated team of reviewers who ensure the quality of the database. We thank the associate editor and two anonymous reviewers for comments that improved this manuscript. Author contributions CTC, WKC, JHW, and REM conceptualized the data processing to assign urban scores. CTC, MBL, and REM designed the study. CTC performed the data analysis with insight from WKC and AGBP. All authors contributed to drafting and editing the manuscript. Data accessibility Code and data necessary to reproduce these analyses have been uploaded as supplementary material alongside this manuscript, and will be made available as a permanently archived Zenodo repository upon acceptance of the manuscript. -

Mammals of the Avon Region

Mammals of the Avon Region By Mandy Bamford, Rowan Inglis and Katie Watson Foreword by Dr. Tony Friend R N V E M E O N G T E O H F T W A E I S L T A E R R N A U S T 1 2 Contents Foreword 6 Introduction 8 Fauna conservation rankings 25 Species name Common name Family Status Page Tachyglossus aculeatus Short-beaked echidna Tachyglossidae not listed 28 Dasyurus geoffroii Chuditch Dasyuridae vulnerable 30 Phascogale calura Red-tailed phascogale Dasyuridae endangered 32 phascogale tapoatafa Brush-tailed phascogale Dasyuridae vulnerable 34 Ningaui yvonnae Southern ningaui Dasyuridae not listed 36 Antechinomys laniger Kultarr Dasyuridae not listed 38 Sminthopsis crassicaudata Fat-tailed dunnart Dasyuridae not listed 40 Sminthopsis dolichura Little long-tailed dunnart Dasyuridae not listed 42 Sminthopsis gilberti Gilbert’s dunnart Dasyuridae not listed 44 Sminthopsis granulipes White-tailed dunnart Dasyuridae not listed 46 Myrmecobius fasciatus Numbat Myrmecobiidae vulnerable 48 Chaeropus ecaudatus Pig-footed bandicoot Peramelinae presumed extinct 50 Isoodon obesulus Quenda Peramelinae priority 5 52 Species name Common name Family Status Page Perameles bougainville Western-barred bandicoot Peramelinae endangered 54 Macrotis lagotis Bilby Peramelinae vulnerable 56 Cercartetus concinnus Western pygmy possum Burramyidae not listed 58 Tarsipes rostratus Honey possum Tarsipedoidea not listed 60 Trichosurus vulpecula Common brushtail possum Phalangeridae not listed 62 Bettongia lesueur Burrowing bettong Potoroidae vulnerable 64 Potorous platyops Broad-faced -

Accepted Version

ACCEPTED VERSION Patrick L. Taggart Are blood haemoglobin concentrations a reliable indicator of parasitism and individual condition in New Holland honeyeaters (Phylidonyris novaehollandiae)? Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia, 2016; 140(1):17-27 © 2016 Royal Society of South Australia "This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia on 01 Mar 2016 available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03721426.2016.1151970 PERMISSIONS http://authorservices.taylorandfrancis.com/sharing-your-work/ Accepted Manuscript (AM) As a Taylor & Francis author, you can post your Accepted Manuscript (AM) on your personal website at any point after publication of your article (this includes posting to Facebook, Google groups, and LinkedIn, and linking from Twitter). To encourage citation of your work we recommend that you insert a link from your posted AM to the published article on Taylor & Francis Online with the following text: “This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in [JOURNAL TITLE] on [date of publication], available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/[Article DOI].” For example: “This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis Group in Africa Review on 17/04/2014, available online:http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/12345678.1234.123456. N.B. Using a real DOI will form a link to the Version of Record on Taylor & Francis Online. The AM is defined by the National Information Standards Organization as: “The version of a journal article that has been accepted for publication in a journal.” This means the version that has been through peer review and been accepted by a journal editor. -

December 2016 Vol

Castlemaine Naturalist December 2016 Vol. 41.11 #449 Monthly newsletter of the Castlemaine Field Naturalists Club Inc. Powerful Owl chick - photo Noel Young Moths of Victoria – and Castlemaine CFNC members were fortunate to have Marilyn Hewish as guest speaker at the Club’s November meeting. Marilyn is a distinguished naturalist, who received the Australian Natural History Medallion in 2013 for her decades of work on Australian birds and her more recent contributions to studies of the moths of Victoria. She told us how she had become a “moth addict” and that most of the commonly stated ways to distinguish moths and butterflies are myths – some moths are active during daylight, many are highly coloured (not “brown and boring”), some have clubbed antennae. The technical difference is in the way the forewings and hindwings are linked – needing microscopic examination! Moths and their caterpillars play a major ecological role, for example as a significant food source for birds, bats, reptiles, small mammals and larger invertebrates. Some caterpillars feed on leaf litter, thus recycling nutrients and reducing the intensity of fires. Some day-flying moths pollinate flowers. Though butterflies are more familiar to most naturalists, they are far outnumbered by moth species in Australia: about 400 species of butterflies and more than 20,000 moths (the exact figure is not known). The studies of Victorian moths are in very early stages compared to our knowledge of Australian birds. Marilyn and Dean are frequently in the field – at night (even when cold and wet), surveying moths at sites across Victoria. They often record large extensions in distributions, species not previously known from the state, and even species new to science. -

Guidelines for the Development of Bird Habitat

Guidelines for the Development of Bird Habitat User: Local Councils, Urban and Development Planners (local, state and private) and the Housing Industry Why design landscapes for birds? The design and planning of residential housing and new developments can make a critical difference to the environmental sustainability of our cities and towns and the conservation of urban wildlife. Birds are the most conspicuous animal species in urban environments, making them outstanding indicators of our performance in meeting obligations to sustainability1 Unfortunately in most urban areas bird diversity continues to decline, indicating our continuing failure to maintain suitable habitat. Small native birds such as the Red-browed Finch and Superb Fairy-wren in eastern Australia, are becoming less common, replaced by dominant and aggressive species. In NSW these include the Noisy Miner, Pied Currawong and the Rainbow Lorikeet, but other states may have a different mix. Areas of high human-population density are the places where we have the resources to design and manage habitat to meet the specific needs of particular fauna. In the long-term, by meeting these needs we can facilitate an increase in local populations or possibly the return of a species that was previously present. In managing such large areas of urban habitat, you have a great influence on the bird community. However many new developments on the urban fringe, often near bushland and having conservation potential, have rather created habitat conditions that reduce diversity of local native bird species and encourage one or two larger species to dominate the area. 1 All local governments in Australia are legally obliged to operate according to the principles of ecologically sustainable development.