THE HONEYEATERS of KANGAROO ISLAND HUGH FOB,D Accepted August

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat

Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Dedicated bird enthusiasts have kindly contributed to this sequence of 106 bird species spotted in the habitat over the last few years Kookaburra Red-browed Finch Black-faced Cuckoo- shrike Magpie-lark Tawny Frogmouth Noisy Miner Spotted Dove [1] Crested Pigeon Australian Raven Olive-backed Oriole Whistling Kite Grey Butcherbird Pied Butcherbird Australian Magpie Noisy Friarbird Galah Long-billed Corella Eastern Rosella Yellow-tailed black Rainbow Lorikeet Scaly-breasted Lorikeet Cockatoo Tawny Frogmouth c Noeline Karlson [1] ( ) Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Variegated Fairy- Yellow Faced Superb Fairy-wren White Cheeked Scarlet Honeyeater Blue-faced Honeyeater wren Honeyeater Honeyeater White-throated Brown Gerygone Brown Thornbill Yellow Thornbill Eastern Yellow Robin Silvereye Gerygone White-browed Eastern Spinebill [2] Spotted Pardalote Grey Fantail Little Wattlebird Red Wattlebird Scrubwren Willie Wagtail Eastern Whipbird Welcome Swallow Leaden Flycatcher Golden Whistler Rufous Whistler Eastern Spinebill c Noeline Karlson [2] ( ) Common Sea and shore birds Silver Gull White-necked Heron Little Black Australian White Ibis Masked Lapwing Crested Tern Cormorant Little Pied Cormorant White-bellied Sea-Eagle [3] Pelican White-faced Heron Uncommon Sea and shore birds Caspian Tern Pied Cormorant White-necked Heron Great Egret Little Egret Great Cormorant Striated Heron Intermediate Egret [3] White-bellied Sea-Eagle (c) Noeline Karlson Uncommon Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Grey Goshawk Australian Hobby -

Fire Management Newsletter: Eucalyptus: a Complex Challenge

Golden Gate National Recreation Area National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Point Reyes National Seashore EucalyptusEucalyptus A Complex Challenge AUSTRALIA FIRE MANAGEMENT, RESOURCE PROTECTION, AND THE LEGACY OF TASMANIAN BLUE GUM DURING THE AGE OF EXPLORATION, CURIOUS SPECIES dead, dry, oily leaves and debris—that is especially flammable. from around the world captured the imagination, desire and Carried by long swaying branches, fire spreads quickly in enterprising spirit of many different people. With fragrant oil and eucalyptus groves. When there is sufficient dead material in the massive grandeur, eucalyptus trees were imported in great canopy, fire moves easily through the tree tops. numbers from Australia to the Americas, and California became home to many of them. Adaptations to fire include heat-resistant seed capsules which protect the seed for a critical short period when fire reaches the CALIFORNIA Eucalyptus globulus, or Tasmanian blue gum, was first introduced crowns. One study showed that seeds were protected from lethal to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1853 as an ornamental tree. heat penetration for about 4 minutes when capsules were Soon after, it was widely planted for timber production when exposed to 826o F. Following all types of fire, an accelerated seed domestic lumber sources were being depleted. Eucalyptus shed occurs, even when the crowns are only subjected to intense offered hope to the “Hardwood Famine”, which the Bay Area heat without igniting. By reseeding when the litter is burned off, was keenly aware of, after rebuilding from the 1906 earthquake. blue gum eucalyptus like many other species takes advantage of the freshly uncovered soil that is available after a fire. -

Bush Birds Making Your Place Their Place Too

BUSH BIRDS MAKING YOUR PLACE THEIR PLACE TOO This fact sheet explains which bush birds may be present or absent from your place and what you can do to encourage a greater diversity to live with you. The drier, settled areas of southern Tasmania, and whistlers. Some, like Pink Robin and Scrubtit, compared to other places, still have much of their prefer wet forest and others, such as Forty- original bush. In many instances the clearing for spotted Pardalote are rarely seen outside their agriculture and urban development has produced preferred specialist habitat. a mosaic of habitats including highly modified The Yellow-throated Honeyeater needs bush with Some species live in the same bush all year, treeless paddocks through to fully vegetated hills, good structure, as it forages high in trees but nests whilst others migrate in the late autumn to in which many species of birds still thrive. But bird in shrubs close to the ground. increase their foraging range, descend in species begin to decline or will be absent where altitude or cross Bass Strait to spend their intact patches of bush are lost or if this mosaic winter on mainland Australia. Bush habitat also BUSH BIRDS’ HOMES becomes too highly modified. supports birds of prey, water birds in creeks and Just like us, birds have three basic needs: About 60 species of birds live within the bush of wetlands, and a small number of other species 1. Their preferred food. southern Tasmania. Common groups of species using heaths or grasslands on the forest fringe. include honeyeaters, parrots, robins, pardalotes 2. -

Recent Honeyeater Migration in Southern Australia

June 2010 223 Recent Honeyeater Migration in Southern Australia BRYAN T HAYWOOD Abstract be seen moving through areas of south-eastern Australia during autumn (Ford 1983; Simpson & A conspicuous migration of honeyeaters particularly Day 1996). On occasions Fuscous Honeyeaters Yellow-faced Honeyeater, Lichenostomus chrysops, have been reported migrating in company with and White-naped Honeyeater, Melithreptus lunatus, Yellow-faced Honeyeaters, but only in small was observed in the SE of South Australia during numbers (Blakers et al., 1984). May and June 2007. A particularly significant day was 12 May 2007 when both species were Movements of honeyeaters throughout southern observed moving in mixed flocks in westerly and Australia are also predominantly up the east northerly directions in five different locations in the coast with birds moving from Victoria and New SE of South Australia. Migration of Yellow-faced South Wales (Hindwood 1956;Munro, Wiltschko Honeyeater and White-naped Honeyeater is not and Wiltschko 1993; Munro and Munro 1998) limited to following the coastline in the SE of South into southern Queensland. The timing and Australia, but also inland. During this migration direction at which these movements occur has period small numbers of Fuscous Honeyeater, L. been under considerable study with findings fuscus, were also observed. The broad-scale nature that birds (heading up the east coast) actually of these movements over the period April to June change from a north-easterly to north-westerly 2007 was indicated by records from south-western direction during this migration period. This Victoria, various locations in the SE of South change in direction is partly dictated by changes Australia, Adelaide and as far west as the Mid North in landscape features, but when Yellow-faced of SA. -

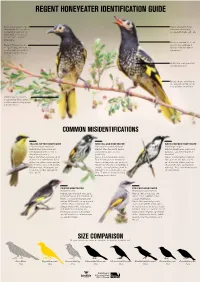

Regent Honeyeater Identification Guide

REGENT HONEYEATER IDENTIFICATION GUIDE Broad patch of bare warty Males call prominently, skin around the eye, which whereas females only is smaller in young birds occasionally make soft calls. and females. Best seen at close range or with binoculars. Plumage around the head Regent Honeyeaters are and neck is solid black 20-24 cm long, with females giving a slightly hooded smaller and having duller appearance. plumage than the males. Distinctive scalloped (not streaked) breast. Broad stripes of yellow in the wing when folded, and very prominent in flight. From below the tail is a bright yellow. From behind it’s black bordered by bright yellow feathers. COMMON MISIDENTIFICATIONS YELLOW-TUFTED HONEYEATER NEW HOLLAND HONEYEATER WHITE-CHEEKED HONEYEATER Lichenostomus melanops Phylidonyris novaehollandiae Phylidonyris niger Habitat: Box-Gum-Ironbark Habitat: Woodland with heathy Habitat: Heathlands, parks and woodlands and forest with a understorey, gardens and gardens, less commonly open shrubby understorey. parklands. woodland. Notes: Common, sedentary bird Notes: Often misidentified as a Notes: Similar to New Holland of temperate woodlands. Has a Regent Honeyeater; commonly Honeyeaters, but have a large distinctive yellow crown and ear seen in urban parks and gardens. patch of white feathers in their tuft in a black face, with a bright Distinctive white breast with black cheek and a dark eye (no white yellow throat. Underparts are streaks, several patches of white eye ring). Also have white breast plain dirty yellow, upperparts around the face, and a white eye streaked black. olive-green. ring. Tend to be in small, noisy and aggressive flocks. PAINTED HONEYEATER CRESCENT HONEYEATER Grantiella picta Phylidonyris pyrrhopterus Habitat: Box-Ironbark woodland, Habitat: Wetter habitats like particularly with fruiting mistletoe forest, dense woodland and Notes: A seasonal migrant, only coastal heathlands. -

RATIOS of SCARLET HONEYEATER Myzomela Sanguinolenta

Corella,1995, 19(2): 5F60 ABUNDANCE,SITE FIDELITY,MORPHOMETRICS AND SEX RATIOSOF SCARLETHONEYEATER Myzomela sanguinolenta AT A SITE IN SOUTH.EASTQUEENSLAND S.J. M. BLABER 33 wuduru Roa,.I.Cornubia- Quecnsland'll3(l Reftifttl 5 ADtil. I9I)1 Scarlet Honeyealerswere banded at a study site at N/ounlCotton, souih-east Queensland from 19861o 1993. The sileconsisted of sclerophyllwoodland, creek vegelation and a ruralgarden. There was a markedseasonal change in ScarletHoneyeater abundance, with numbersincreasing lrom a minrmumin Marchto a maximumin August followed by a declineto December.No birdswere recorded In Januaryor February.There was no significantinterannual variation rn meanlrapping rales. The numbersof birdscaught each month were significantly and negatively correlated with ralnfall. Changes in abundancemay nol be relatedlo availabilityof blossoms.Morphomelric data indicatelhat males havesigniJicantly greater wing, lail and tarsuslengths than females, and are heavier.The sex ralio was skewedin favour ol males (3:2) and this phenomenonis discussed.Rekap data show that a small proportionof birdsreturn annLrally to the studysile and areresident for partof theyear. The remaining birdswere assumed 1o be passagemigranls, possibly moving lnland to lhe DividingRange during the wel season. INTRODUCTION bccn rcportcd (I-ongrnorc l99l). Outsiclc Aust- ralia, publishcd information is limitcd to casual The nominate subspecies of thc scxually observations(e.g. Forbes l{ttt5) and trrief studies dinrorphicScarlet Honeyeater M_vzom - eI a sanguino (c.g. Ripley 1959). lentu sanguinolentaoccurs along most of the east coirstof Australia.with an additionall0 subspccies As part of ir long-tcrrn banding study in sub- extending in an arc through the Lesser Sundas coastalsouth-cast Oueensland, particular attention (e.g. -

Accepted Version

ACCEPTED VERSION Patrick L. Taggart Are blood haemoglobin concentrations a reliable indicator of parasitism and individual condition in New Holland honeyeaters (Phylidonyris novaehollandiae)? Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia, 2016; 140(1):17-27 © 2016 Royal Society of South Australia "This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia on 01 Mar 2016 available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03721426.2016.1151970 PERMISSIONS http://authorservices.taylorandfrancis.com/sharing-your-work/ Accepted Manuscript (AM) As a Taylor & Francis author, you can post your Accepted Manuscript (AM) on your personal website at any point after publication of your article (this includes posting to Facebook, Google groups, and LinkedIn, and linking from Twitter). To encourage citation of your work we recommend that you insert a link from your posted AM to the published article on Taylor & Francis Online with the following text: “This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in [JOURNAL TITLE] on [date of publication], available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/[Article DOI].” For example: “This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis Group in Africa Review on 17/04/2014, available online:http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/12345678.1234.123456. N.B. Using a real DOI will form a link to the Version of Record on Taylor & Francis Online. The AM is defined by the National Information Standards Organization as: “The version of a journal article that has been accepted for publication in a journal.” This means the version that has been through peer review and been accepted by a journal editor. -

New England Peppermint (Eucalyptus Nova-Anglica) Grassy

Advice to the Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities from the Threatened Species Scientific Committee on an Amendment to the List of Threatened Ecological Communities under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) 1. Name of the ecological community New England Peppermint (Eucalyptus nova-anglica) Grassy Woodlands This advice follows the assessment of two public nominations to list the ‘New England Peppermint (Eucalyptus nova-anglica) Woodlands on Sediment on the Northern Tablelands’ and the ‘New England Peppermint (Eucalyptus nova-anglica) Woodlands on Basalt on the Northern Tablelands’ as threatened ecological communities under the EPBC Act. The Threatened Species Scientific Committee (the Committee) recommends that the national ecological community be renamed New England Peppermint (Eucalyptus nova-anglica) Grassy Woodlands. The name reflects the fact that the definition of the ecological community has been expanded to include all grassy woodlands dominated or co-dominated by Eucalyptus nova-anglica (New England Peppermint), in New South Wales and Queensland. Also the occurrence of the ecological community extends beyond the New England Tableland Bioregion, into adjacent areas of the New South Wales North Coast and the Nandewar bioregions. Part of the national ecological community is listed as endangered in New South Wales, as ‘New England Peppermint (Eucalyptus nova-anglica) Woodland on Basalts and Sediments in the New England Tableland Bioregion’ (NSW Scientific Committee, 2003); and, as an endangered Regional Ecosystem in Queensland ‘RE 13.3.2 Eucalyptus nova-anglica ± E. dalrympleana subsp. heptantha open-forest or woodland’ (Qld Herbarium, 2009). 2. Public Consultation A technical workshop with experts on the ecological community was held in 2005. -

Eastern Australia: October-November 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN AUSTRALIA: From Top to Bottom 23rd October – 11th November 2016 The bird of the trip, the very impressive POWERFUL OWL Tour Leader: Laurie Ross All photos in this report were taken by Laurie Ross/Tropical Birding. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 INTRODUCTION The Eastern Australia Set Departure Tour introduces a huge amount of new birds and families to the majority of the group. We started the tour in Cairns in Far North Queensland, where we found ourselves surrounded by multiple habitats from the tidal mudflats of the Cairns Esplanade, the Great Barrier Reef and its sandy cays, lush lowland and highland rainforests of the Atherton Tablelands, and we even made it to the edge of the Outback near Mount Carbine; the next leg of the tour took us south to Southeast Queensland where we spent time in temperate rainforests and wet sclerophyll forests within Lamington National Park. The third, and my favorite leg, of the tour took us down to New South Wales, where we birded a huge variety of new habitats from coastal heathland to rocky shorelines and temperate rainforests in Royal National Park, to the mallee and brigalow of Inland New South Wales. The fourth and final leg of the tour saw us on the beautiful island state of Tasmania, where we found all 13 “Tassie” endemics. We had a huge list of highlights, from finding a roosting Lesser Sooty Owl in Malanda; to finding two roosting Powerful Owls near Brisbane; to having an Albert’s Lyrebird walk out in front of us at O Reilly’s; to seeing the rare and endangered Regent Honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, and finding the endangered Swift Parrot on Bruny Island, in Tasmania. -

2015-Birds-Of-ML1.Pdf

FREE presents Birds of Mawson Lakes Linda Vining & MikeBIRDS Flynn of Mawson Lakes An online book available at www.mawsonlakesliving.info Republished as an ebook in 2015 First Published in 2013 Published by Mawson Lakes Living Magazine 43 Parkview Drive Mawson Lakes 5095 SOUTH AUSTRALIA Ph: +61 8 8260 7077 [email protected] www.mawsonlakesliving.info Photography and words by Mike Flynn Cover: New Holland Honeyeater. See page 22 for description © All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording or otherwise, without credit to the publisher. BIRDS inof MawsonMawson LakesLakes 3 Introduction What bird is that? Birdlife in Mawson Lakes is abundant and adds a wonderful dimension to our natural environment. Next time you go outside just listen to the sounds around you. The air is always filled with bird song. Birds bring great pleasure to the people of Mawson Lakes. There is nothing more arresting than a mother bird and her chicks swimming on the lakes in the spring. What a show stopper. The huge variety of birds provides magnificent opportunities for photographers. One of these is amateur photographer Mike Flynn who lives at Shearwater. Since coming to live at Mawson Lakes he has become an avid bird watcher and photographer. I often hear people ask: “What bird is that?” This book, brought to you by Mawson Lakes Living, is designed to answer this question by identifying birds commonly seen in Mawson Lakes and providing basic information on where to find them, what they eat and their distinctive features. -

Spring Bird Communities of a High-Altitude Area of the Gloucester Tops, New South Wales

Australian Field Ornithology 2018, 35, 21–29 http://dx.doi.org/10.20938/afo35021029 Spring bird communities of a high-altitude area of the Gloucester Tops, New South Wales Alan Stuart1 and Mike Newman2 181 Queens Road, New Lambton NSW 2305, Australia. Email: [email protected] 272 Axiom Way, Acton Park TAS 7021, Australia. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Annual spring surveys between 2010 and 2016 in a 5000-ha area in the Gloucester Tops in New South Wales recorded 71 bird species. All the study area was at altitudes >1100 m. The monitoring program was carried out with involvement of a team of volunteers, who regularly surveyed 21 1-km transects, for a total of 289 surveys. The study area was within the Barrington Tops and Gloucester Tops Key Biodiversity Area (KBA). The trigger species for the KBA listing was the Rufous Scrub-bird Atrichornis rufescens, which was found to have a widespread distribution in the study area, with an average Reporting Rate (RR) of 56.5%. Another species cited in the KBA nomination, the Flame Robin Petroica phoenicea, had an average RR of 12.6% but with considerable annual variation. Although the Flame Robin had a widespread distribution, one-third of all records came from just two of the 21 survey transects. Thirty-seven bird species had RRs >4% in the study area and were distributed across many transects. Of these, 20 species were relatively common, with RRs >20%, and they occurred in all or nearly all of the survey transects. Introduction shrubs such as Banksia species (Binns 1995). -

Conserving Migratory and Nomadic Species

Conserving migratory and nomadic species Claire Alice Runge A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2015 School of Biological Sciences Abstract Migration is an incredible phenomenon. Across cultures it moves and inspires us, from the first song of a migratory bird arriving in spring, to the sight of thousands of migratory wildebeest thundering across African plains. Not only important to us as humans, migratory species play a major role in ecosystem functioning across the globe. Migratory species use multiple landscapes and can have dramatically different ecologies across their lifecycle, making huge contributions to resource fluxes and nutrient transport. However, migrants around the world are in decline. In this thesis I examine our conservation response to these declines, exploring how well current approaches account for the unique needs of migratory species, and develop ways to improve on these. The movements of migratory species across time and space make their conservation a multidimensional problem, requiring actions to mitigate threats across jurisdictions, across habitat types and across time. Incorporating such linkages can make a dramatic difference to conservation success, yet migratory species are often treated for the purposes of conservation planning as if they were stationary, ignoring the complex linkages between sites and resources. In this thesis I measure how well existing global conservation networks represent these linkages, discovering major gaps in our current protection of migratory species. I then go on to develop tools for improving conservation of migratory species across two areas: prioritizing actions across species and designing conservation networks. Protected areas are one of our most effective conservation tools, and expanding the global protected area estate remains a priority at an international level.