Territorial Behaviour of a Regent Honeyeater at Feeding Sites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indonesia's Exquisite Birds of Paradise

INDONESIA'S EXQUISITE BIRDS OF PARADISE Whether you are a mere nestling who is new to bird watching, a Halmehera: Standard-wing (Wallace’s) Bird-of fully-fledged birder, or a seasoned twitcher, this 10-day (9-night) ornithological adventure through the remote, rainforest-clad islands of northern Raja Ampat and North Maluku, which includes a two-night stay at the famed Weda Resort on Halmahera, is a fantastic opportunity to add some significant numbers to your life lists. No other feathered family is as beautiful, or displays such diversity of plumage, extravagant decoration, and courtship behaviour as the ostentatious Bird of Paradise. In the company of our guest expert, Dr. Kees Groeneboer, we will be in hot pursuit of as many as six or seven species of these fabled shapeshifters, which strut, dazzle and dance in costumes worthy of the stage. -Paradise, Paradise Crow. Special birds in the Weda-Forest of Raja Ampat is one of the most noteworthy ecological niches on Halmahera Moluccan Goshawk, Moluccan Scrubfowl, Bare-eyed the planet, where you can snorkel within a below-surface world Rail, Drummer Rail, Scarletbreasted Fruit-Dove, Blue-capped reminiscent of a living kaleidoscope, while marveling at Fruit-Dove, Cinnamon-bellied Imperial Pigeon, Chattering Lory, above-surface views – and birds, which are among the most White (Alba) Cockatoo, Moluccan Cuckoo, Goliath Coucal, Blue stunning that you are likely to behold in a lifetime. Meanwhile, and-white Kingfisher, Sombre Kingfisher, Azure (Purple) Halmahera, in the North Maluku province, is where some of the Dollarbird, Ivory-breasted Pitta, Halmahera Cuckooshrike, world’s rarest and least-known birds occur. -

Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat

Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Dedicated bird enthusiasts have kindly contributed to this sequence of 106 bird species spotted in the habitat over the last few years Kookaburra Red-browed Finch Black-faced Cuckoo- shrike Magpie-lark Tawny Frogmouth Noisy Miner Spotted Dove [1] Crested Pigeon Australian Raven Olive-backed Oriole Whistling Kite Grey Butcherbird Pied Butcherbird Australian Magpie Noisy Friarbird Galah Long-billed Corella Eastern Rosella Yellow-tailed black Rainbow Lorikeet Scaly-breasted Lorikeet Cockatoo Tawny Frogmouth c Noeline Karlson [1] ( ) Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Variegated Fairy- Yellow Faced Superb Fairy-wren White Cheeked Scarlet Honeyeater Blue-faced Honeyeater wren Honeyeater Honeyeater White-throated Brown Gerygone Brown Thornbill Yellow Thornbill Eastern Yellow Robin Silvereye Gerygone White-browed Eastern Spinebill [2] Spotted Pardalote Grey Fantail Little Wattlebird Red Wattlebird Scrubwren Willie Wagtail Eastern Whipbird Welcome Swallow Leaden Flycatcher Golden Whistler Rufous Whistler Eastern Spinebill c Noeline Karlson [2] ( ) Common Sea and shore birds Silver Gull White-necked Heron Little Black Australian White Ibis Masked Lapwing Crested Tern Cormorant Little Pied Cormorant White-bellied Sea-Eagle [3] Pelican White-faced Heron Uncommon Sea and shore birds Caspian Tern Pied Cormorant White-necked Heron Great Egret Little Egret Great Cormorant Striated Heron Intermediate Egret [3] White-bellied Sea-Eagle (c) Noeline Karlson Uncommon Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Grey Goshawk Australian Hobby -

Management and Breeding of Birds of Paradise (Family Paradisaeidae) at the Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation

Management and breeding of Birds of Paradise (family Paradisaeidae) at the Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation. By Richard Switzer Bird Curator, Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation. Presentation for Aviary Congress Singapore, November 2008 Introduction to Birds of Paradise in the Wild Taxonomy The family Paradisaeidae is in the order Passeriformes. In the past decade since the publication of Frith and Beehler (1998), the taxonomy of the family Paradisaeidae has been re-evaluated considerably. Frith and Beehler (1998) listed 42 species in 17 genera. However, the monotypic genus Macgregoria (MacGregor’s Bird of Paradise) has been re-classified in the family Meliphagidae (Honeyeaters). Similarly, 3 species in 2 genera (Cnemophilus and Loboparadisea) – formerly described as the “Wide-gaped Birds of Paradise” – have been re-classified as members of the family Melanocharitidae (Berrypeckers and Longbills) (Cracraft and Feinstein 2000). Additionally the two genera of Sicklebills (Epimachus and Drepanornis) are now considered to be combined as the one genus Epimachus. These changes reduce the total number of genera in the family Paradisaeidae to 13. However, despite the elimination of the 4 species mentioned above, 3 species have been newly described – Berlepsch's Parotia (P. berlepschi), Eastern or Helen’s Parotia (P. helenae) and the Eastern or Growling Riflebird (P. intercedens). The Berlepsch’s Parotia was once considered to be a subspecies of the Carola's Parotia. It was previously known only from four female specimens, discovered in 1985. It was rediscovered during a Conservation International expedition in 2005 and was photographed for the first time. The Eastern Parotia, also known as Helena's Parotia, is sometimes considered to be a subspecies of Lawes's Parotia, but differs in the male’s frontal crest and the female's dorsal plumage colours. -

Fire Management Newsletter: Eucalyptus: a Complex Challenge

Golden Gate National Recreation Area National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Point Reyes National Seashore EucalyptusEucalyptus A Complex Challenge AUSTRALIA FIRE MANAGEMENT, RESOURCE PROTECTION, AND THE LEGACY OF TASMANIAN BLUE GUM DURING THE AGE OF EXPLORATION, CURIOUS SPECIES dead, dry, oily leaves and debris—that is especially flammable. from around the world captured the imagination, desire and Carried by long swaying branches, fire spreads quickly in enterprising spirit of many different people. With fragrant oil and eucalyptus groves. When there is sufficient dead material in the massive grandeur, eucalyptus trees were imported in great canopy, fire moves easily through the tree tops. numbers from Australia to the Americas, and California became home to many of them. Adaptations to fire include heat-resistant seed capsules which protect the seed for a critical short period when fire reaches the CALIFORNIA Eucalyptus globulus, or Tasmanian blue gum, was first introduced crowns. One study showed that seeds were protected from lethal to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1853 as an ornamental tree. heat penetration for about 4 minutes when capsules were Soon after, it was widely planted for timber production when exposed to 826o F. Following all types of fire, an accelerated seed domestic lumber sources were being depleted. Eucalyptus shed occurs, even when the crowns are only subjected to intense offered hope to the “Hardwood Famine”, which the Bay Area heat without igniting. By reseeding when the litter is burned off, was keenly aware of, after rebuilding from the 1906 earthquake. blue gum eucalyptus like many other species takes advantage of the freshly uncovered soil that is available after a fire. -

THE HONEYEATERS of KANGAROO ISLAND HUGH FOB,D Accepted August

134 SOUTH AUsTRALIAN ORNITHOLOGIST, 21 THE HONEYEATERS OF KANGAROO ISLAND HUGH FOB,D Accepted August. 1976 Kangaroo Island is the third largest of Aus In the present paper I discuss morphological tralia's islands (4,500 sq. km) and has been and ecological differences between populations separated from the neighbouring Fleurieu of several species of honeyeaters from Kangaroo Peninsula for 10,000 years (Abbott 1973). A Island and the Fleurieu Peninsula respectively, mere 14 km separates island from mainland; and speculate on how these differences origin but the island has a distinct avifauna and lacks ated. many of the mainland species. This paucity of DIFFERENCES IN PLUMAGE species has been attributed to extinction after The Kangaroo Island population of Purple isolation and failure to recolonise (Abbott gaped Honeyeater was described as larger and 1974, 1976), and to lack of suitable habitat brighter than the mainland population by (Ford and Paton 1975). Mathews (1923-4). Brightness of plumage is a Nine species of honeyeaters are resident on very subjective characteristic, and in my opinion Kangaroo Island. The Purple-gaped Honey Purple-gaped Honeyeaters on Kangaroo Island eater Lichenostomus cratitius (formerly Meli are, if anything, duller than mainland ones. phaga cratitia) was described as a distinct sub Condon (1951) says that the gape of this species by Mathews (1923-24); and Keast species is invariably yellow on Kangaroo Island (1961) mentions that six other species differ in instead of lilac, although he later comments a minor way from mainland populations and that lilac-gaped individuals do occur on the may merit subspecific status. -

Brown Honeyeater Lichmera Indistincta Species No.: 597 Band Size: 02 (01) AY

Australian Bird Study Association Inc. – Bird in the Hand (Second Edition), published on www.absa.asn.au - Revised August 2019 Brown Honeyeater Lichmera indistincta Species No.: 597 Band Size: 02 (01) AY Morphometrics: Adult Male Adult Female THL: 30.7 – 36 mm 30.3 – 34.1 mm Wing Length: 54 – 76 mm 53 – 68 mm Wing Span: > 220 mm < 215 mm Tail: 48 – 64 mm 47 – 58 mm Tarsus: 15.8 – 19.5 mm 15.3 – 17.3 mm Weight: 7.9 – 13.6 g 7.0 – 12.1 g Ageing and sexing: Adult Male Adult Female Juvenile Forehead, crown dark brown with thick dark, brown with olive like female, but loose & & nape: brownish-grey fringes or wash or greenish; downy texture; silvery grey; Bill: fully black; black, but often with mostly black with yellow pinkish-white base; -ish tinge near base; Gape black when breeding, but yellow, yellowish white, puffy yellow; yellow or yellowish white pinkish white or buff- when not breeding; yellow; Chin & throat: brownish grey; brownish grey with straw similar to female, but -yellow fringes; looser and downy; Juvenile does not have yellow triangle feather tuft behind eye until about three months after fledging; Immature plumage is very similar to adult female, but may retain juvenile remiges, rectrices and upper wing coverts; Adult plumage is acquired at approximately 15 months - so age adults (2+) and Immatures either (2) or (1) if very young and downy. Apart from plumage differences, males appear considerably larger than females, but there Is a large overlap in most measurements, except in wingspan; Female alone incubates. -

Tropical Birding Tour Report

AUSTRALIA’S TOP END Victoria River to Kakadu 9 – 17 October 2009 Tour Leader: Iain Campbell Having run the Northern Territory trip every year since 2005, and multiple times in some years, I figured it really is about time that I wrote a trip report for this tour. The tour program changed this year as it was just so dry in central Australia, we decided to limit the tour to the Top End where the birding is always spectacular, and skip the Central Australia section where birding is beginning to feel like pulling teeth; so you end up with a shorter but jam-packed tour laden with parrots, pigeons, finches, and honeyeaters. Throw in some amazing scenery, rock art, big crocs, and thriving aboriginal culture you have a fantastic tour. As for the list, we pretty much got everything, as this is the kind of tour where by the nature of the birding, you can leave with very few gaps in the list. 9 October: Around Darwin The Top End trip started around three in the afternoon, and the very first thing we did was shoot out to Fogg Dam. This is a wetlands to behold, as you drive along a causeway with hundreds of Intermediate Egrets, Magpie-Geese, Pied Herons, Green Pygmy-geese, Royal Spoonbills, Rajah Shelducks, and Comb-crested Jacanas all close and very easy to see. While we were watching the waterbirds, we had tens of Whistling Kites and Black Kites circling overhead. When I was a child birder and thought of the Top End, Fogg Dam and it's birds was the image in my mind, so it is always great to see the reaction of others when they see it for the first time. -

National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera Phrygia)

National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia) April 2016 1 The Species Profile and Threats Database pages linked to this recovery plan is obtainable from: http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2016. The National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia) is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This report should be attributed as ‘National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia), Commonwealth of Australia 2016’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright, [name of third party] ’. Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. Image credits Front Cover: Regent honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, NSW. (© Copyright, Dean Ingwersen). 2 -

Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2016 Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation: Investigating different variables in three flowers of the Ecuadorian Cloud Forest: Guzmania jaramilloi, Gasteranthus quitensis, and Besleria solanoides Sophie Wolbert SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Community-Based Research Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, and the Plant Biology Commons Recommended Citation Wolbert, Sophie, "Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation: Investigating different variables in three flowers of the Ecuadorian Cloud Forest: Guzmania jaramilloi, Gasteranthus quitensis, and Besleria solanoides" (2016). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2470. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2470 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wolbert 1 Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation: Investigating different variables in three flowers of the Ecuadorian Cloud Forest: Guzmania jaramilloi, Gasteranthus quitensis, and Besleria solanoides Author: Wolbert, Sophie Academic -

Recent Honeyeater Migration in Southern Australia

June 2010 223 Recent Honeyeater Migration in Southern Australia BRYAN T HAYWOOD Abstract be seen moving through areas of south-eastern Australia during autumn (Ford 1983; Simpson & A conspicuous migration of honeyeaters particularly Day 1996). On occasions Fuscous Honeyeaters Yellow-faced Honeyeater, Lichenostomus chrysops, have been reported migrating in company with and White-naped Honeyeater, Melithreptus lunatus, Yellow-faced Honeyeaters, but only in small was observed in the SE of South Australia during numbers (Blakers et al., 1984). May and June 2007. A particularly significant day was 12 May 2007 when both species were Movements of honeyeaters throughout southern observed moving in mixed flocks in westerly and Australia are also predominantly up the east northerly directions in five different locations in the coast with birds moving from Victoria and New SE of South Australia. Migration of Yellow-faced South Wales (Hindwood 1956;Munro, Wiltschko Honeyeater and White-naped Honeyeater is not and Wiltschko 1993; Munro and Munro 1998) limited to following the coastline in the SE of South into southern Queensland. The timing and Australia, but also inland. During this migration direction at which these movements occur has period small numbers of Fuscous Honeyeater, L. been under considerable study with findings fuscus, were also observed. The broad-scale nature that birds (heading up the east coast) actually of these movements over the period April to June change from a north-easterly to north-westerly 2007 was indicated by records from south-western direction during this migration period. This Victoria, various locations in the SE of South change in direction is partly dictated by changes Australia, Adelaide and as far west as the Mid North in landscape features, but when Yellow-faced of SA. -

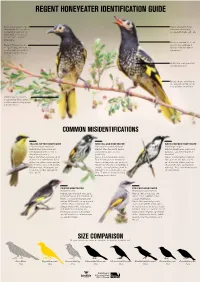

Regent Honeyeater Identification Guide

REGENT HONEYEATER IDENTIFICATION GUIDE Broad patch of bare warty Males call prominently, skin around the eye, which whereas females only is smaller in young birds occasionally make soft calls. and females. Best seen at close range or with binoculars. Plumage around the head Regent Honeyeaters are and neck is solid black 20-24 cm long, with females giving a slightly hooded smaller and having duller appearance. plumage than the males. Distinctive scalloped (not streaked) breast. Broad stripes of yellow in the wing when folded, and very prominent in flight. From below the tail is a bright yellow. From behind it’s black bordered by bright yellow feathers. COMMON MISIDENTIFICATIONS YELLOW-TUFTED HONEYEATER NEW HOLLAND HONEYEATER WHITE-CHEEKED HONEYEATER Lichenostomus melanops Phylidonyris novaehollandiae Phylidonyris niger Habitat: Box-Gum-Ironbark Habitat: Woodland with heathy Habitat: Heathlands, parks and woodlands and forest with a understorey, gardens and gardens, less commonly open shrubby understorey. parklands. woodland. Notes: Common, sedentary bird Notes: Often misidentified as a Notes: Similar to New Holland of temperate woodlands. Has a Regent Honeyeater; commonly Honeyeaters, but have a large distinctive yellow crown and ear seen in urban parks and gardens. patch of white feathers in their tuft in a black face, with a bright Distinctive white breast with black cheek and a dark eye (no white yellow throat. Underparts are streaks, several patches of white eye ring). Also have white breast plain dirty yellow, upperparts around the face, and a white eye streaked black. olive-green. ring. Tend to be in small, noisy and aggressive flocks. PAINTED HONEYEATER CRESCENT HONEYEATER Grantiella picta Phylidonyris pyrrhopterus Habitat: Box-Ironbark woodland, Habitat: Wetter habitats like particularly with fruiting mistletoe forest, dense woodland and Notes: A seasonal migrant, only coastal heathlands. -

RATIOS of SCARLET HONEYEATER Myzomela Sanguinolenta

Corella,1995, 19(2): 5F60 ABUNDANCE,SITE FIDELITY,MORPHOMETRICS AND SEX RATIOSOF SCARLETHONEYEATER Myzomela sanguinolenta AT A SITE IN SOUTH.EASTQUEENSLAND S.J. M. BLABER 33 wuduru Roa,.I.Cornubia- Quecnsland'll3(l Reftifttl 5 ADtil. I9I)1 Scarlet Honeyealerswere banded at a study site at N/ounlCotton, souih-east Queensland from 19861o 1993. The sileconsisted of sclerophyllwoodland, creek vegelation and a ruralgarden. There was a markedseasonal change in ScarletHoneyeater abundance, with numbersincreasing lrom a minrmumin Marchto a maximumin August followed by a declineto December.No birdswere recorded In Januaryor February.There was no significantinterannual variation rn meanlrapping rales. The numbersof birdscaught each month were significantly and negatively correlated with ralnfall. Changes in abundancemay nol be relatedlo availabilityof blossoms.Morphomelric data indicatelhat males havesigniJicantly greater wing, lail and tarsuslengths than females, and are heavier.The sex ralio was skewedin favour ol males (3:2) and this phenomenonis discussed.Rekap data show that a small proportionof birdsreturn annLrally to the studysile and areresident for partof theyear. The remaining birdswere assumed 1o be passagemigranls, possibly moving lnland to lhe DividingRange during the wel season. INTRODUCTION bccn rcportcd (I-ongrnorc l99l). Outsiclc Aust- ralia, publishcd information is limitcd to casual The nominate subspecies of thc scxually observations(e.g. Forbes l{ttt5) and trrief studies dinrorphicScarlet Honeyeater M_vzom - eI a sanguino (c.g. Ripley 1959). lentu sanguinolentaoccurs along most of the east coirstof Australia.with an additionall0 subspccies As part of ir long-tcrrn banding study in sub- extending in an arc through the Lesser Sundas coastalsouth-cast Oueensland, particular attention (e.g.