Regent Honeyeater) Conservation Advice 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera Phrygia)

National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia) April 2016 1 The Species Profile and Threats Database pages linked to this recovery plan is obtainable from: http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2016. The National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia) is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This report should be attributed as ‘National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia), Commonwealth of Australia 2016’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright, [name of third party] ’. Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. Image credits Front Cover: Regent honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, NSW. (© Copyright, Dean Ingwersen). 2 -

The Relationships of the Starlings (Sturnidae: Sturnini) and the Mockingbirds (Sturnidae: Mimini)

THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE STARLINGS (STURNIDAE: STURNINI) AND THE MOCKINGBIRDS (STURNIDAE: MIMINI) CHARLESG. SIBLEYAND JON E. AHLQUIST Departmentof Biologyand PeabodyMuseum of Natural History,Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 USA ABSTRACT.--OldWorld starlingshave been thought to be related to crowsand their allies, to weaverbirds, or to New World troupials. New World mockingbirdsand thrashershave usually been placed near the thrushesand/or wrens. DNA-DNA hybridization data indi- cated that starlingsand mockingbirdsare more closelyrelated to each other than either is to any other living taxon. Some avian systematistsdoubted this conclusion.Therefore, a more extensiveDNA hybridizationstudy was conducted,and a successfulsearch was made for other evidence of the relationshipbetween starlingsand mockingbirds.The resultssup- port our original conclusionthat the two groupsdiverged from a commonancestor in the late Oligoceneor early Miocene, about 23-28 million yearsago, and that their relationship may be expressedin our passerineclassification, based on DNA comparisons,by placing them as sistertribes in the Family Sturnidae,Superfamily Turdoidea, Parvorder Muscicapae, Suborder Passeres.Their next nearest relatives are the members of the Turdidae, including the typical thrushes,erithacine chats,and muscicapineflycatchers. Received 15 March 1983, acceptedI November1983. STARLINGS are confined to the Old World, dine thrushesinclude Turdus,Catharus, Hylocich- mockingbirdsand thrashersto the New World. la, Zootheraand Myadestes.d) Cinclusis -

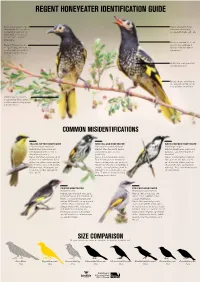

Regent Honeyeater Identification Guide

REGENT HONEYEATER IDENTIFICATION GUIDE Broad patch of bare warty Males call prominently, skin around the eye, which whereas females only is smaller in young birds occasionally make soft calls. and females. Best seen at close range or with binoculars. Plumage around the head Regent Honeyeaters are and neck is solid black 20-24 cm long, with females giving a slightly hooded smaller and having duller appearance. plumage than the males. Distinctive scalloped (not streaked) breast. Broad stripes of yellow in the wing when folded, and very prominent in flight. From below the tail is a bright yellow. From behind it’s black bordered by bright yellow feathers. COMMON MISIDENTIFICATIONS YELLOW-TUFTED HONEYEATER NEW HOLLAND HONEYEATER WHITE-CHEEKED HONEYEATER Lichenostomus melanops Phylidonyris novaehollandiae Phylidonyris niger Habitat: Box-Gum-Ironbark Habitat: Woodland with heathy Habitat: Heathlands, parks and woodlands and forest with a understorey, gardens and gardens, less commonly open shrubby understorey. parklands. woodland. Notes: Common, sedentary bird Notes: Often misidentified as a Notes: Similar to New Holland of temperate woodlands. Has a Regent Honeyeater; commonly Honeyeaters, but have a large distinctive yellow crown and ear seen in urban parks and gardens. patch of white feathers in their tuft in a black face, with a bright Distinctive white breast with black cheek and a dark eye (no white yellow throat. Underparts are streaks, several patches of white eye ring). Also have white breast plain dirty yellow, upperparts around the face, and a white eye streaked black. olive-green. ring. Tend to be in small, noisy and aggressive flocks. PAINTED HONEYEATER CRESCENT HONEYEATER Grantiella picta Phylidonyris pyrrhopterus Habitat: Box-Ironbark woodland, Habitat: Wetter habitats like particularly with fruiting mistletoe forest, dense woodland and Notes: A seasonal migrant, only coastal heathlands. -

South Eastern Australia Temperate Woodlands

Conservation Management Zones of Australia South Eastern Australia Temperate Woodlands Prepared by the Department of the Environment Acknowledgements This project and its associated products are the result of collaboration between the Department of the Environment’s Biodiversity Conservation Division and the Environmental Resources Information Network (ERIN). Invaluable input, advice and support were provided by staff and leading researchers from across the Department of Environment (DotE), Department of Agriculture (DoA), the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and the academic community. We would particularly like to thank staff within the Wildlife, Heritage and Marine Division, Parks Australia and the Environment Assessment and Compliance Division of DotE; Nyree Stenekes and Robert Kancans (DoA), Sue McIntyre (CSIRO), Richard Hobbs (University of Western Australia), Michael Hutchinson (ANU); David Lindenmayer and Emma Burns (ANU); and Gilly Llewellyn, Martin Taylor and other staff from the World Wildlife Fund for their generosity and advice. Special thanks to CSIRO researchers Kristen Williams and Simon Ferrier whose modelling of biodiversity patterns underpinned identification of the Conservation Management Zones of Australia. Image Credits Front Cover: Yanga or Murrumbidgee Valley National Park – Paul Childs/OEH Page 4: River Red Gums (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) – Allan Fox Page 10: Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia) – Trent Browning Page 16: Gunbower Creek – Arthur Mostead Page 19: Eastern Grey -

Comparative Bathing Behavior in Some Australian Birds

J. Field Ornithol., 62(3):386-389 COMPARATIVE BATHING BEHAVIOR IN SOME AUSTRALIAN BIRDS N. A.M. VE•EEK Departmentof BiologicalSciences SimonFraser University Burnaby,British ColumbiaV5A IS6, Canada Abstract.--The bathingbehavior of Alcedinidae(2 species),Dicruridae (1), Meliphagidae (16), Meropidae (1), Muscicapidae (5) and Zosteropidae(1) is describedand compared with that of other species.The birds were observedfrom a blind while they bathed in a water hole with a sloping shore line and flanked on one side by shrubs.Two forms of bathing were noted: diving from shrubsand wading into shallow water. Although more data are needed,it is suggestedthat the bathing methodsused by birds differ at the generic level and not necessarilyat the family level. ESTUDIO COMPARATIVO DE LA CONDUCTA DE BAI•ARSE POR ALGUNAS AVES AUSTRALIANAS Sinopsis.--Sedescribe y comparala conductade bafiarsede Alcedinidae(2 especies),Di- cruridae(1), Meliphagidae (16), Meropidae (1), Muscicapidae(5) y Zosteropidae(1) con la de otras especies.Las avesse observarondesde escondijos mientras se bafiabanen un ojo de agua flanquedoen un lado pot arbustos.Se noratondos formas de bafiarse:tiffindose en clavado desdeun arbusto y andando o brincando desdela orilla hacia agua de poca pro- fundidad.Aunque se necesitanmils datos,sugiero que el m•todo de bafiarseutilizado pot las avesdifiere a nivel de g•nero y no necesariamentea nivel de familia. Although someforms of feather maintenancebehavior have been stud- ied in detail (e.g.,preening, Hatch et al. 1986, Ierseland Bol 1958) others (e.g., bathing) are rarely mentionedin the bird literature (Burtt 1983). As most feather maintenanceactivities occur infrequently and unpre- dictablyand are often of short duration, they are difficult to study sys- tematically.Simmons (1964) and Slessers(1970) reportedon the different bathing techniquesof birds and made the first attemptsto compareand interpret them in terms of morphologyand ecology.The observations here reported show that theseinterpretations may have to be modified. -

Or POLYMYODI): Oscines (Songbirds

Text extracted from Gill B.J.; Bell, B.D.; Chambers, G.K.; Medway, D.G.; Palma, R.L.; Scofield, R.P.; Tennyson, A.J.D.; Worthy, T.H. 2010. Checklist of the birds of New Zealand, Norfolk and Macquarie Islands, and the Ross Dependency, Antarctica. 4th edition. Wellington, Te Papa Press and Ornithological Society of New Zealand. Pages 275, 279-280, 288 & 291-292. Order PASSERIFORMES: Passerine (Perching) Birds See Christidis & Boles (2008) for a review of recent studies relevant to the higher-level systematics of the passerine birds. Suborder PASSERES (or POLYMYODI): Oscines (Songbirds) The arrangement of songbirds in the 1970 Checklist (Checklist Committee 1970) was based on the premise that the species endemic to the Australasian region were derived directly from Eurasian groups and belonged in Old World families (e.g. Gerygone and Petroica in Muscicapidae). The 1990 Checklist (Checklist Committee 1990) followed the Australian lead in allocating various native songbirds to their own Australasian families (e.g. Gerygone to Acanthizidae, and Petroica to Eopsaltriidae), but the sequence was still based largely on the old Peters-Mayr arrangement. Since the late 1980s, when the 1990 Checklist was finalised, evidence from molecular biology, especially DNA studies, has shown that most of the Australian and New Zealand endemic songbirds are the product of a major Australasian radiation parallel to the radiation of songbirds in Eurasia and elsewhere. Many superficial morphological and ecological similarities between Australasian and Eurasian songbirds are the result of convergent evolution. Sibley & Ahlquist (1985, 1990) and Sibley et al. (1988) recognised a division of the songbirds into two groups which were called Corvida and Passerida (Sibley & Ahlquist 1990). -

Regent Honeyeater Version Has Been Prepared for Web Publication

#41 This Action Statement was first published in 1993 and remains current. This Regent Honeyeater version has been prepared for web publication. It Xanthomyza phrygia retains the original text of the action statement, although contact information, the distribution map and the illustration may have been updated. © The State of Victoria, Department of Sustainability and Environment, 2003 Published by the Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria. Regent Honeyeater (Xanthomyza phrygia) Distribution in Victoria (DSE 2002) 8 Nicholson Street, (Illustration by John Las Gourgues) East Melbourne, distributed within about 300 km of the Victoria 3002 Australia Description and Distribution The Regent Honeyeater (Xanthomyza eastern Australian coast from about 100 km This publication may be of phrygia Shaw 1794) is a specialised, north of Brisbane to Adelaide. However, it is assistance to you but the medium-size honeyeater (Family no longer found in South Australia (Franklin State of Victoria and its Meliphagidae) inhabiting drier open forests & Menkhorst 1988) or western Victoria employees do not guarantee and woodlands in south-eastern Australia. (Franklin et al. 1989). Further, population that the publication is Adults weigh 41 to 46 g. Plumage is dispersion within this distribution is now without flaw of any kind or predominantly black with bright yellow patchy. The species is highly mobile, but is wholly appropriate for little information is available on movement your particular purposes edges to tail and wing feathers. Body patterns. and therefore disclaims all feathers, except for the head and neck, are liability for any error, loss broadly edged in pale yellow or white In Victoria, Regent Honeyeaters occur or other consequence which (Longmore 1991). -

REGENT HONEYEATER Anthochaera Phrygia Critically Endangered

Zoos Victoria’s Fighting Extinction Species REGENT HONEYEATER Anthochaera phrygia Critically Endangered Fewer than 400 Regent Honeyeaters are A successful captive-breeding and release thought to occur in the wild, the result of program, led by Taronga Conservation ongoing declines over the past 30 years. Society Australia, Birdlife Australia and the Population modelling indicates a higher than Victorian Department of Environment, Land, 50% probability of extinction during the next Water and Planning has been underway 20 years, placing it among Australia’s most since 1995 to bolster the wild population. imperilled birds. The ongoing declines of Regent Zoos Victoria will increase its support for Honeyeaters in the wild indicate that it is time this species by increasing the holding and to expand the captive program to provide a breeding capacity of Regent Honeyeaters greater level of insurance against extinction. across the captive breeding program. Zoos Victoria is committed to Fighting Extinction We are focused on working with partners to secure the survival of our priority species before it is too late. The ongoing declines of Regent Honeyeaters in the wild indicate that it is time to expand the captive program to provide a greater level of insurance against extinction. Halting the declining trend for this iconic honeyeater requires the dedicated efforts of many partners. Strong foundations are in place, but it will take time to increase the extent and quality of Regent Honeyeater habitat. Importantly, critical support measures are in place, including field surveys, while efforts to mitigate threats in the wild take effect. KEY PROGRAM OBJECTIVES A successful captive-breeding and release • Increase the size of the insurance program, led by Taronga Conservation population. -

Regent Honeyeater: Icon Threatened Species

Regent Honeyeater: icon threatened species Scientific name: Xanthomyza phrygia Other common names: Turkey Bird, Embroidered Honeyeater Conservation status: Endangered in NSW and Australia How do I recognise it? blakelyi) and River Oak (Casuarina cunninghamiana). The Regent Honeyeater is a medium sized bird (about the size of a starling). What does it eat? A spectacularly marked bird, it has a black beak, black head and a bare Regent Honeyeaters principally feed cream to pinkish patch of warty skin on: around their eye. The back and • Nectar of eucalypts (see those breast appear scaly (pale lemon and listed above). black), while the wings and tail are • Nectar and fruit of mistle- edged with bright yellow. Males and toes including; Needle-leaf females are similarly coloured. Regent Honeyeater (Photo: N Lazarus) Mistletoe (Amyema cambagei), A. miquelii It is often found high in the tree the western slopes, especially box- Box Mistletoe ( ) and A. pendu- canopy of flowering eucalypts, and ironbark and riparian woodlands. Drooping Mistletoe ( lum often occurs with Lorikeets and Key habitat trees include: Mugga ) Friarbirds. Ironbark (Eucalyptus sideroxylon), • Sugary exudates from insects Yellow Box (E. melliodora), White when nectar is scarce, and Within the Border Rivers Gwydir Box (E. albens), Grey Box (E. • Insects themselves during the Catchment, the only similarly sized moluccana), Blakely’s Red Gum (E. breeding season. and coloured bird is the Painted Honeyeater. The Painted Honeyeater Mature Grassy Box Woodlands are important Regent Honeyeater habitat (Photo: W Hawes) is distinguished by its solid black back, white throat and breast, lack of a warty patch about the eye and pink beak. -

Loss of Vocal Culture and Fitness Costs in a Critically Endangered Songbird

Loss of vocal culture and fitness costs in a royalsocietypublishing.org/journal/rspb critically endangered songbird Ross Crates1, Naomi Langmore2, Louis Ranjard2, Dejan Stojanovic1, Laura Rayner1, Dean Ingwersen3 and Robert Heinsohn1 Research 1Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian National University, Linnaeus Way, Acton, Canberra 2601, Australia Cite this article: Crates R, Langmore N, 2Research School of Biology, Australian National University, 46 Sullivan’s Creek Rd, Acton, Ranjard L, Stojanovic D, Rayner L, Ingwersen Canberra 2601, Australia 3BirdLife Australia, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia D, Heinsohn R. 2021 Loss of vocal culture and fitness costs in a critically endangered RC, 0000-0002-7660-309X; NL, 0000-0003-3368-6697; DS, 0000-0002-1176-3244; RH, 0000-0002-2514-9448 songbird. Proc. R. Soc. B 288: 20210225. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2021.0225 Cultures in humans and other species are maintained through interactions among conspecifics. Declines in population density could be exacerbated by culture loss, thereby linking culture to conservation. We combined his- torical recordings, citizen science and breeding data to assess the impact Received: 28 January 2021 of severe population decline on song culture, song complexity and individ- Accepted: 19 February 2021 ual fitness in critically endangered regent honeyeaters (Anthochaera phrygia). Song production in the remaining wild males varied dramatically, with 27% singing songs that differed from the regional cultural norm. Twelve per cent of males, occurring in areas of particularly low population density, comple- tely failed to sing any species-specific songs and instead sang other species’ Subject Category: songs. Atypical song production was associated with reduced individual fit- Global change and conservation ness, as males singing atypical songs were less likely to pair or nest than males that sang the regional cultural norm. -

'Island Rule' Apply to Birds?

Lincoln University Digital Thesis Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: you will use the copy only for the purposes of research or private study you will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of the thesis and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate you will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Does the ‘island rule’ apply to birds? An analysis of morphological variation between insular and mainland birds from the Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic region A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (Conservation and Ecology) at Lincoln University by Elisa Diana Ruiz Ramos Lincoln University 2014 Abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (Conservation and Ecology) Abstract Does the ‘island rule’ apply to birds? An analysis of morphological variation between insular and mainland birds from the Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic region by Elisa Diana Ruiz Ramos The ‘island rule’ states that large animals become smaller and small animals become larger on islands. Morphological shifts on islands have been generalized for all vertebrates as a strategy to better exploit limited resources in constrained areas with low interspecific competition and predation pressures. In the case of birds, most of the studies that validate this rule have focused on passerines, and it is unclear about whether the rule applies to other Orders. -

Subalular Apterium in Birds

THE AUK A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY VoL. 89 Ai, mL 1972 No. 2 SUBALULAR APTERIUM IN BIRDS WILLIAM G. GEORGE AND CLARK L. CASLER AN apterium, which evidently has remainedundescribed, exists under the alula of many avian speciesbut not by any meansin all groups. We first noted it in the Snakebird (Anhinga anhinga) in which the un- featheredarea, measuringabout 850 sq mm, is createdby an absenceof most upper median and other small upper wing covertsassociated with primaries1 (innermost) through6 (Figures 1A, lB). In an ordinary museumskin this apterium is apt to escapenotice, being shut away behind a dry, inflexible alula. Details of subalular plumage are difficult to see in skins for the same reason,and at first we soughtto limit our investigationto specimensin spirits and to freshly- collectedand living birds. But this kind of material proved available for only a few forms. Consequentlywe often resortedto dampeningthe wings of skins with a weak solutionof ethyl alcohol and examiningas much of the subalular area as could be glimpsedby slightly deflecting the alula. The present paper attempts to summarizeour still very incomplete knowledgeof the presenceand absenceof subalular apteria throughout the class. As used below, the term "apterium" refers to an absenceor size reduction of coverts which, as we interpret the evolutionary evi- dence, converted a once almost fully feathered region into a partly naked expanse. A wide variety of conditions intermediate between a well-marked apterium, as seen in Anhinga, and a feathered subalular region,as seenin most species,of courseexists. A showof skin may arise variously from loss of a few or many coverts,from size reductionof a few or many coverts,and from combinationsof both thesecircumstances.