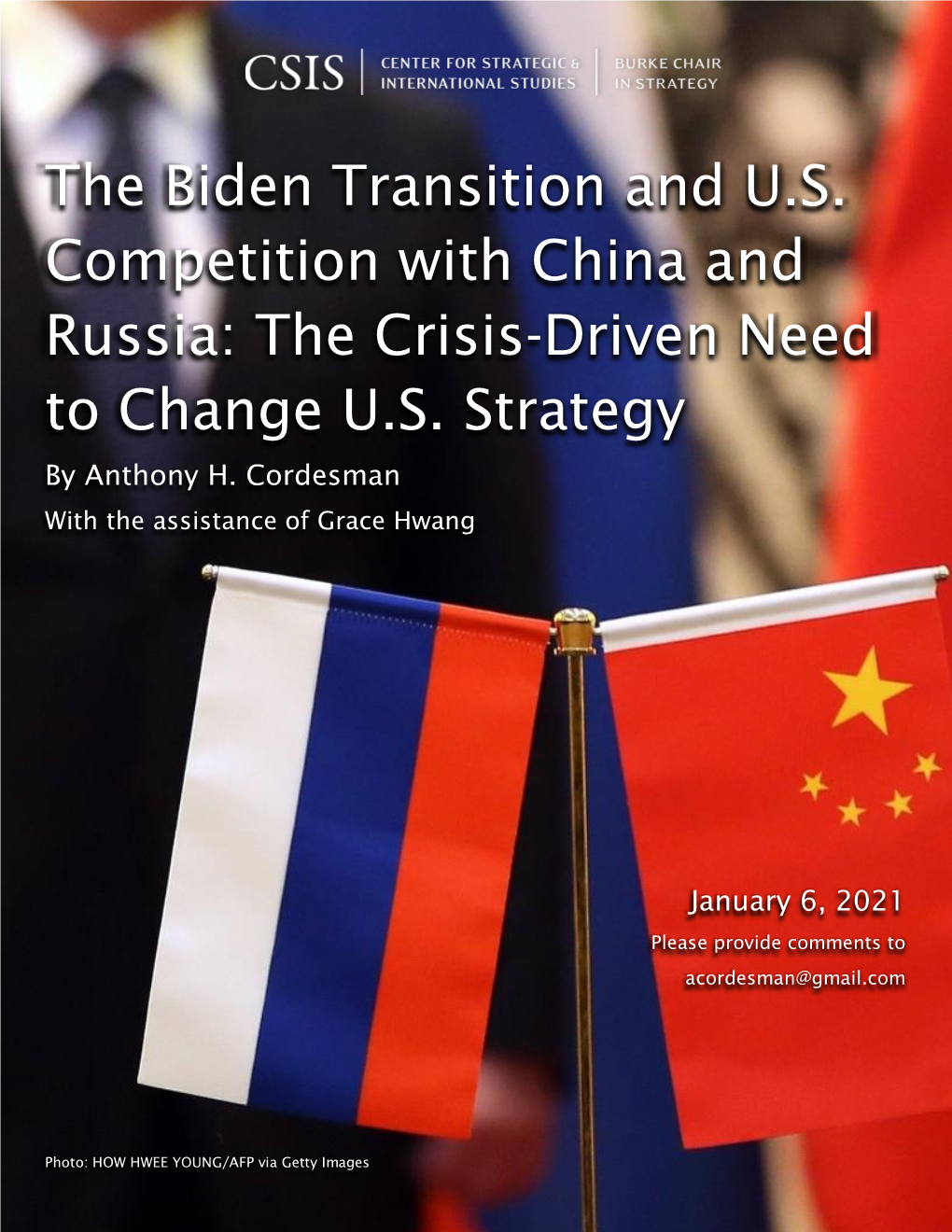

The Biden Transition and U.S. Competition with China and Russia: the Crisis-Driven Need to Change U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ab World's Wer Plant

8 Friday, March 2, 2018 Graphic of weaponry presented by Vladimir Putin Russia unveils ‘invincible’ UAE to open Arab world’s first nuclear power plant nuclear weapons Moscow 15 years, sought to win unilateral than any other vessel would make it Russian complaints. ussia has tested an array of advantages over Russia, introduced immune to enemy intercept. “No one has listened to us,” he new strategic nuclear weapons unlawful sanctions aimed to contain Putin accompanied his statement said. “You listen to us now.” Rthat can’t be intercepted, President our country’s development: all what to an audience of hundreds of He emphasized that Russia is Vladimir Putin announced you wanted to impede with your senior officials and lawmakers with concerned about the Pentagon-led yesterday, marking a technological policies have already happened,” videos and computer images of new nuclear review released earlier this breakthrough that could dramatically he said. “You have failed to contain weapons, which were shown on giant year that envisaged the development increase Russia’s military capability, Russia.” screens at a conference hall near the of low-yield nuclear weapons, saying boost the Kremlin’s global position The announcement comes as Kremlin. that it could lower the threshold for and also raise Western concerns Putin is set to easily win another six- A computer video showed using nuclear weapons. about a potential renewed arms race year presidential term in the March the drone being launched by a “We will interpret any use of in the 21st century. 18 election. submarine, cruising over the seabed, nuclear weapons against Russia and Speaking in a state-of-the-nation He said that the nuclear-powered hitting an aircraft carrier and also its allies no matter how powerful speech, Putin said the weapons include cruise missile tested last fall has a exploding near the shore. -

News Brief 1

February 2019 Volume 20, Issue 2 Lest We Forget — Inside This Issue: Meeting minutes 2 “The USSVI Submariner’s Creed” Lost Boats 3 To perpetuate the memory of our shipmates who Undersea Warfare Hist 3 gave their lives in the pursuit of their duties while Cobia working party 4 serving their country. That their dedication, deeds, Chicago Auto Show 5 and supreme sacrifice be a constant source of USO at O’Hare visit 7 motivation toward greater accomplishments. Pledge loyalty and patriotism to the United States of Contact information 9 America and its Constitution. Application form 10 News Brief 1. Next Meeting: At 1100, third Saturday of each month at the Knollwood Sportsman’s Club. Mark your calendars for these upcoming dates: a. FEBRUARY 16 b. MARCH 16 c. APRIL 20 2. Duty Cook Roster: a. FEBRUARY – MAURICE YOUNG b. MARCH – BRET ZACHER’S SUPERB CORNED BEEF c. APRIL – SEE YOUR NAME HERE! 3. February Birthdays: Leon Lemma 6th; Eric Hansknecht 11th; Larry Heckelsmiller 12th; Scott Jaklin 17th. Happy Birthday, Shipmates! 4. Shop for USS ILLINOIS-themed items and help the FRG raise money here: https://shop.spreadshirt.com/uss-illinois-786-frg/. 5. Become part of the ‘Lifetime Alliance Between Crew and Citizens” of the USS ILLINOIS by joining the 786 Club. Annual dues are modest. The only requirement for membership is a desire to support the crew. Our efforts are greatly appreciated. You can become part of the ILLINOIS Family today. Contact Chris Gaines or go to www.786Club.org. Crash Dive Meeting Minutes Will repeat next year on January 26, 2019 December 7, 2019. -

A Soviet Nuclear Sub Was Running out of Air and Needed to Surface During

NUCLEAR WEAPONS: An accident waiting to happen We know of nearly 70 military nuclear accidents since 1950 (mainly from the US and UK from which information is more forthcoming). These include several incidents of lost or missing nuclear weapons. Many incidents have involved explosions and/or fires or some other mechanism for spreading fissile material. There were also a num- ber of times when a nuclear war was narrowly averted. There are undoubtedly many more we do not (and may never) know about. Jul 27, 1956: US bomber skids off runway at RAF Lakenheath, crashing into a storage unit containing three atomic bombs. Weapons engulfed in flames before fire fighters were able to extinguish the fire. May 22, 1957: Nuclear bomb accidentally dropped in the New Mexico desert. Sep 25, 1959: Aircraft in trouble drops two large fuel tanks shortly after take-off at Greenham Common, one hits a parked aircraft nearby which has a nuclear bomb on board. Two are killed in resulting fire which takes 16 hours to extinguish. Area around base is radioactively contaminated. The incident remains secret until uncovered by CND in 1996. Jan 23, 1961: Three people are killed when an aircraft carrying nuclear bombs crashes in North Carolina. Three of four arming devices on one bomb trigger, meaning it was only one safety mechanism away from detonation. Dec 5, 1965: A nuclear-armed air- plane rolls off the aircraft carrier USS Ticonderoga and sinks in 16,000 feet of water off the coast of Japan. Jan 17, 1966: Two bombers collide while refuelling midair above Palomares, near the Spanish coast. -

Safeguards, Non-Proliferation and Peaceful Nuclear Energy

Chapter 8 SAFEGUARDS, NON-PROLIFERATION AND PEACEFUL NUCLEAR ENERGY © M. Ragheb 9/2/2021 “Stalemate, Hello, A strange game. The only winning move is not to play. How about a nice game of Chess?” War Games movie, 1983. “We live in a world where there is more and more information, and less and less meaning.” “It is dangerous to unmask images, since they dissimulate the fact that there is nothing behind them.” Jean Baudrillard, “Simulacra and Simulation” “I know not with what weapons World War III will be fought, but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones.” Albert Einstein “For nothing can seem foul to those that win.” William Shakespeare "Simpler explanations are, other things being equal, generally better than more complex ones.” “Among competing hypotheses, the one that makes the fewest assumptions should be selected.” “It is futile to do with more things that which can be done with fewer.” Occam’s Razor Principle, William of Ockham, Medieval philosopher. “We are to admit no more causes of natural things than such as are both true and sufficient to explain their appearances. Therefore, to the same natural effects we must, so far as possible, assign the same causes.” Isaac Newton “Whenever possible, substitute constructions out of known entities for inferences to unknown entities.” Bertrand Russell “If a thing can be done adequately by means of one, it is superfluous to do it by means of several; for we observe that nature does not employ two instruments [if] one suffices.” Thomas Aquinas “If your enemy is secure at all points, be prepared for him. -

Critical MASS Nuclear Proliferation in the Middle East N I the M N the Iddle E Iddle Ast Andrew F

CRITI C AL MASS: NU C LEAR PROLIFERATIO CRITICAL MASS NUCLEAR PROLIFERATION IN THE MIddLE EAst N I N THE M IDDLE E AST ANDREW F. KREPINEVICH F. ANDREW 1667 K Street, NW, Suite 900 Washington, DC 20006 Tel. 202-331-7990 • Fax 202-331-8019 www.csbaonline.org ANDREW F. KREPINEVICH CRITICAL MASS: NUCLEAR PROLIFERATION IN THE MIDDLE EAST BY ANDREW F. KREPINEVICH 2013 About the Authors Dr. Andrew F. Krepinevich, Jr. is the President of the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, which he joined following a 21- year career in the U.S. Army. He has served in the Department of De- fense’s Office of Net Assessment, on the personal staff of three secretar- ies of defense, the National Defense Panel, the Defense Science Board Task Force on Joint Experimentation, and the Defense Policy Board. He is the author of 7 Deadly Scenarios: A Military Futurist Explores War in the 21st Century and The Army and Vietnam. A West Point graduate, he holds an M.P.A. and a Ph.D. from Harvard University. Acknowledgments The author would like to thank Eric Edelman, Evan Montgomery, Jim Thomas, and Barry Watts for reviewing and commenting on earlier ver- sions of this report. Thanks are also in order for Eric Lindsey for his re- search and editorial support and to Kamilla Gunzinger for her copyedit- ing. Eric Lindsey also provided graphics support that greatly enhanced the report’s presentation. Any shortcomings in this assessment, however, are the author’s re- sponsibility and the author’s alone. © 2013 Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. -

Reductions Without Regret: Defining the Needed Capabilities 10 September 2013

SRNL-STI-2013-00552 Reductions without Regret: Defining the Needed Capabilities 10 September 2013 John A. Swegle Douglas J. Tincher The analysis contained herein is that of the authors and does not reflect the views or positions of the Savannah River National Laboratory, the National Nuclear Security Administration, or the U.S. Department of Energy. Savannah River National Laboratory Aiken, SC 29808 John A. Swegle, 735-11A, Room 113, (803)725-3515 Douglas J. Tincher, 735A, Room B102, (803)725-4167 Reductions without Regret: Defining the Needed Capabilities John A. Swegle and Douglas J. Tincher Savannah River National Laboratory This is the second of three papers (in addition to an introductory summary) aimed at providing a framework for evaluating future reductions or modifications of the U.S. nuclear force, first by considering previous instances in which nuclear-force capabilities were eliminated; second by looking forward into at least the foreseeable future at the features of global and regional deterrence (recognizing that new weapon systems currently projected will have expected lifetimes stretching beyond our ability to predict the future); and third by providing examples of past or possible undesirable outcomes in the shaping of the future nuclear force, as well as some closing thoughts for the future. This paper begins with a discussion of the current nuclear force and the plans and procurement programs for the modernization of that force. Current weapon systems and warheads were conceived and built decades ago, and procurement programs have begun for the modernization or replacement of major elements of the nuclear force: the heavy bomber, the air-launched cruise missile, the ICBMs, and the ballistic-missile submarines. -

The Cuban Missile Crisis: the Soviet View by Sherry Nay

Torch Magazine • Fall 2015 The Cuban Missile Crisis: The Soviet View By Sherry Nay October 27, 1962. This was the day devastating German invasion of World in history in which unclear orders, War II. misunderstood intentions, and brinkmanship could have caused the This history produced an ongoing end of civilization as we know it. This search for security and a desire to is not an overstatement. American avoid war. Soviet Premier Nikita missiles with nuclear bombs were Khrushchev had personally exper- ready. Soviet missiles with nuclear ienced the invasion of his village by the bombs were ready. Soviet submarines Austrians in World War I; during the armed with nuclear torpedoes thought German invasion of World War II, he they were being attacked. Orders was at the decisive and deadly battle Sherry Nay to their commanders had not been of Stalingrad. Interestingly, both received. Soviet and Warsaw Pact forces Khrushchev and Kennedy served on Sherry Nay grew up in Powell, were on full alert. The United States the allied side during the war. Both lost Wyoming, east of Yellowstone Park and armed forces were on Defcon 2, the close family members—Kennedy a close to the Montana border. After earning a bachelor’s degree at readiness step next to nuclear war. brother, and Khrushchev a son. what is now Northern Colorado University, she taught at Wasson High School Many now alive remember the Cold war rivalry, with its history of in Colorado Springs. After getting an Cuban Missile Crisis, possibly for ideological, political and military MA from the University of Colorado, she distinct moments such as Adlai competition, played heavily on the spent two years in Colorado Springs Stevenson’s “until hell freezes over” minds of Soviet leaders, Khrushchev working for the Social Services depart- ment before moving to Nyack, New York. -

A Geostrategic Primer STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 29

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 29 Russian Challenges from Now into the Next Generation: A Geostrategic Primer by Peter B. Zwack and Marie-Charlotte Pierre Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, and Center for the Study of Weapons of Mass Destruction. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the unified combatant commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Vladimir Putin meets in the Kremlin with the leaders of the Federation Council, the State Duma, and dedicated committees of both chambers, December 25, 2018. (President of Russia Web site/Kremlin.ru) Russian Challenges from Now into the Next Generation Russian Challenges from Now into the Next Generation: A Geostrategic Primer By Peter B. Zwack and Marie-Charlotte Pierre Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 29 Series Editor: Thomas F. Lynch III National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. March 2019 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

Alliance Airborne Anti-Submarine Warfare

June 2016 JAPCC Alliance Airborne Anti-Submarine Warfare A Forecast for Maritime Air ASW in the Future Operational Environment Joint Air Power Competence Centre von-Seydlitz-Kaserne Römerstraße 140 | 47546 Kalkar (Germany) | www.japcc.org Warfare Anti-Submarine Airborne Alliance Joint Air Power Competence Centre Cover picture © US Navy © This work is copyrighted. No part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission. Inquiries should be made to: The Editor, Joint Air Power Competence Centre (JAPCC), [email protected] Disclaimer This publication is a product of the JAPCC. It does not represent the opinions or policies of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and is designed to provide an independent overview, analysis, food for thought and recommendations regarding a possible way ahead on the subject. Author Commander William Perkins (USA N), JAPCC Contributions: Commander Natale Pizzimenti (ITA N), JAPCC Release This document is releasable to the Public. Portions of the document may be quoted without permission, provided a standard source credit is included. Published and distributed by The Joint Air Power Competence Centre von-Seydlitz-Kaserne Römerstraße 140 47546 Kalkar Germany Telephone: +49 (0) 2824 90 2201 Facsimile: +49 (0) 2824 90 2208 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.japcc.org Denotes images digitally manipulated FROM: The Executive Director of the Joint Air Power Competence Centre (JAPCC) SUBJECT: A Forecast for Maritime Air ASW in the Future Operational Environment DISTRIBUTION: All NATO Commands, Nations, Ministries of Defence and Relevant Organizations The Russian Federation has increasingly been exercising its military might in areas adjacent to NATO Nations. From hybrid warfare missions against Georgia to paramilitary operations in Crimea, the Russian Federation has used its land-based military to influence regional events in furtherance of their strategic goals. -

Sustaining the U.S. Nuclear Deterrent the Lrso and Gbsd

SUSTAINING THE U.S. NUCLEAR DETERRENT THE LRSO AND GBSD MARK GUNZINGER CARL REHBERG GILLIAN EVANS SUSTAINING THE U.S. NUCLEAR DETERRENT THE LRSO AND GBSD MARK GUNZINGER CARL REHBERG GILLIAN EVANS 2018 ABOUT THE CENTER FOR STRATEGIC AND BUDGETARY ASSESSMENTS (CSBA) The Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments is an independent, nonpartisan policy research institute established to promote innovative thinking and debate about national security strategy and investment options. CSBA’s analysis focuses on key questions related to existing and emerging threats to U.S. national security, and its goal is to enable policymakers to make informed decisions on matters of strategy, security policy, and resource allocation. ©2018 Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. All rights reserved. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Mark Gunzinger is a Senior Fellow at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. Mr. Gunzinger has served as the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Forces, Transformation and Resources. A retired Air Force Colonel and Command Pilot, he joined the Office of the Secretary of Defense in 2004. Mark was appointed to the Senior Executive Service and served as Principal Director of the Department’s central staff for the 2005–2006 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR). Following the QDR, he served as Director for Defense Transformation, Force Planning and Resources on the National Security Council staff. Mr. Gunzinger holds an M.S. in National Security Strategy from the National War College, a Master of Airpower Art and Science degree from the School of Advanced Air and Space Studies, an M.P.A. from Central Michigan University, and a B.S. -

Cuban Missile Crisis and Its Implications for Scotland Today

Scottish CND - Education Pack The most dangerous moment in human history 1 The Cuban Missile Crisis and its implications for Scotland today. John Ainslie, SCND, October 2012 On the evening of Friday 26 October 1962 General Issa Pliyev, Commander of Soviet Forces in Cuba, sent a report to his superiors in Moscow. He was in charge of the large military force, including 160 nuclear weapons, which Nikita Khrushchev had deployed to the island, to “throw a hedgehog down the pants of Uncle Sam”. 2 Pliyev was expecting American aircraft to launch a massive bombing campaign at dawn the next day. He ordered the radar systems at Surface to Air Missile (SAM) sites around the island to be switched on for the first time. Nuclear warheads were moved from two central stores and deployed with their missile regiments. Three FKR cruise-missile launchers were moved to their firing position, ready to launch a nuclear attack on the US base at Guantanamo 3 Bay. Nuclear-armed FKR Cruise Missile in Cuba in October 1962. These missiles were not detected by US intelligence. Photograph provided by the Cuban government in 2002. 1 Arthur Schlesinger, biographer of John F Kennedy described the Cuban Missile Crisis as “the most dangerous moment of human history”. The critical day of the crisis was Saturday 27th October. 2 Comment by Khrushchev to his Defence Minister, Rodion Malinovsky, in April 1962. Reported in One Minute to Midnight, Michael Dobbs, which is the main source for this paper, p 47. www.nuclearweaponsdebate.org Cuban Missile Crisis The arsenal under Pliyev’s control included 36 R-12 missiles which could reach Washington and New York. -

Sustaining the U.S. Nuclear Deterrent: the LRSO and GBSD

Sustaining the U.S. Nuclear Deterrent: the LRSO and GBSD Mark Gunzinger, Carl Rehberg, and Gillian Evans Overview • Why this report? • Factors that should shape future requirements for the U.S. triad • ALCM modernization and the LRSO • Minuteman III modernization and the GBSD • Summary 2 Background • The U.S. triad consists of long-range bombers that carry nuclear gravity weapons and cruise missiles, ICBMs, and SSBNs • All DoD Nuclear Posture Reviews since the Cold Wars (NPR 1994, 2001, 2010, 2018) supported the need to maintain a strong and credible triad o However, multiple major triad modernization programs have been truncated (such as the B-2 and Advanced Cruise Missile programs), delayed (ICBM replacement), or cancelled (previous stealth bomber program) • Russia and China are aggressively modernizing their nuclear forces • Russia has violated the 1987 INF Treaty, China’s nuclear inventory is not constrained by an arms control agreement • The proliferation of missile and other technologies enabled North Korea to fast-track its development of nuclear weapons; Iran continues to develop relevant capabilities 3 A Cold War-era force 1954 Chevy Bel Air 1970 Ford Pinto 1984 Ford Escort 1980 Oldsmobile Cutlass 1962 Ford Fusion 1993 Ford Probe 1950s 1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s 2000s B-52 ALCM B-2 Delivered 1993 - 2000 Delivered 1980 - 1986 Delivered 1954 - 1962 Minuteman III Minuteman Delivered 1970 - 1977 Silos B-1B First built in 1962 Delivered 1984 – 1988 (now conventional only) 4 Funding for DoD’s Strategic Forces (Major Force Program-1) • FY1962: About 22% of DoD’s TOA ($68.9B in FY2018 dollars) • FY1962 to end of Cold War: Averaged 9.6% of annual TOA ($38.6B in FY2018 dollars) • FY1992 to FY2017: Averaged 2.4% of annual TOA ($12.6B in FY2018 dollars) o FY2010 was the nadir at 1.4% of TOA o 2016-2017 jumped from 1.9% to 2.5% of TOA, largest increase since 1983-1984 o Little force modernization 5 U.S.