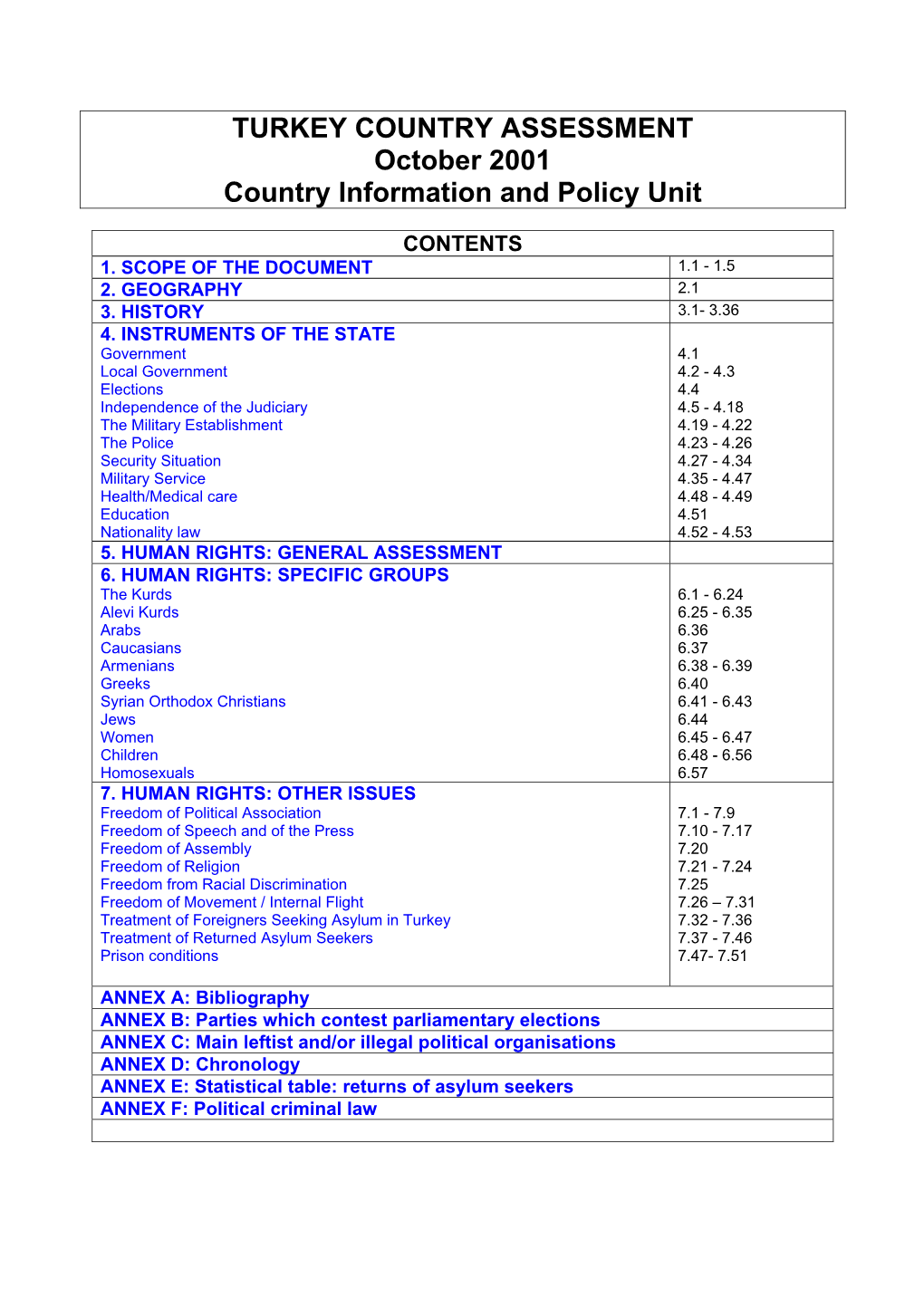

TURKEY COUNTRY ASSESSMENT October 2001 Country Information and Policy Unit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

At the Nexus of Nationalism and Islamism: Seyyid Ahmet Arvasi and the Intellectual History of Conservative Nationalism

At the Nexus of Nationalism and Islamism: Seyyid Ahmet Arvasi and the Intellectual History of Conservative Nationalism Tasha Duberstein A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree for Master of the Arts University of Washington 2020 Committee Selim Sırrı Kuru Arbella Bet-Shlimon Program authorized to offer degree: The Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies 1 © Copyright 2020 Tasha Duberstein 2 University of Washington Abstract At the Nexus of Nationalism and Islamism: Seyyid Ahmet Arvasi and the Intellectual History of Conservative Nationalism Tasha Duberstein Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Selim Sırrı Kuru Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations This paper offers an analysis of the work of Seyyid Ahmet Arvasi (1932-1988); a highly influential yet understudied ultranationalist intellectual, whose synthesis of Turkish nationalism and Islamism provided the ideological framework for the current Islamist-nationalist ruling alliance in Turkish politics. A prolific author, poet, scholar, and propagandist, Arvasi's Türk-İslam Ülküsü (Turkish-Islamic Ideal) was integral to the formulation of conservative nationalism; a form of cultural and religious nationalism which frames national and religious identity as indivisible and mutually constitutive. However, despite Arvasi's significant contribution to the evolution of conservative nationalism, he remains a relatively obscure intellectual outside of ultranationalist circles, and his work is largely ignored in contemporary histories of political ideology. This study reexamines Ahmet Arvasi's work in tandem with the inception of conservative nationalism and the ascendancy of extremist politics, and concludes that his ideological legacy was fundamental to the consolidation of a right-wing bloc perennially represented by Islamists and nationalists. -

International Migration Statistics in the Mediterranean Countries: Report on the Legal Situation Revised Version

1998 EDITION International Migration Statistics in the Mediterranean Countries: Report on the Legal Situation Revised Version (3/1998/E/no 21) THEME 3 Population EUROPEAN and social EUROSTAT WORKING PAPERS WORKING EUROSTAT COMMISSION 3conditions 5(3257217+(/(*$/6,78$7,21 &217(17 1. Introductory Remarks..................................................................................................6 2. Algeria .........................................................................................................................7 2.1 Country's interest in migration studies and statistics. ........................................7 2.2 Existing legislation.............................................................................................7 2.3 Classification and definition...............................................................................7 2.4 Administration bodies........................................................................................8 2.5 Conditions for entry and stay of aliens ..............................................................8 2.6 Prohibited immigrants........................................................................................8 2.7 Registration of aliens.........................................................................................9 2.8 Rules on departure............................................................................................9 2.9 Other aspect/particular feature..........................................................................9 2.10 Further -

Redalyc.Turkey S Immigration and Emigration Dilemmas at the Gate Of

Migración y Desarrollo ISSN: 1870-7599 [email protected] Red Internacional de Migración y Desarrollo México Avci, Gamze; KIRI¿CI, Kemal Turkeys immigration and emigration dilemmas at the gate of the european union Migración y Desarrollo, núm. 7, segundo semestre, 2006, pp. 123-173 Red Internacional de Migración y Desarrollo Zacatecas, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=66000706 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative TURKEY’S IMMIGRATION AND EMIGRATION DILEMMAS TURKEY’S IMMIGRATION AND EMIGRATION DILEMMAS AT THE GATE OF THE EUROPEAN UNION GAMZE AVCI KEMAL KIRIŞCI* ABSTRACT. This paper examines the emigration and immigration system of Turkey and its cor- related visions of development. For that purpose, the paper will study the major characteristics and dynamics of emigration from Turkey into Europe (in particular Germany and the Nether- lands), and the major impact on host societies as well as on Turkey. The analysis gives particular attention to the extent to which Turkish emigration and the Turkish Diaspora have influenced economic, political and social development in Turkey. In a similar manner, we will examine the evolving nature of immigration into Turkey. Finally, we give attention to the place of these issues in EU–Turkish relations. The parallel development of Turkish migrants becoming per- manent residents in Europe and of Turkey receiving new – potentially permanent – migrants from its surrounding region are discussed with a close look at what kind of impact this has on Turkey itself. -

1442643* Cerd/C/Tur/4-6

United Nations CERD/C/TUR/4-6 International Convention on Distr.: General 17 April 2014 the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination Original: English Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 9 of the Convention Combined fourth to sixth periodic reports of States parties due in 2013 Turkey* [Date received: 10 February 2014] * The present document is being issued without formal editing. GE.14-42643 *1442643* CERD/C/TUR/4-6 Contents Paragraphs Page I. Introduction............................................................................................................. 1–9 3 II. Information on specific articles............................................................................... 10–78 4 Article 1 ............................................................................................................... 10–23 4 Article 2 ............................................................................................................... 24–63 6 Article 3 ............................................................................................................... 64–65 15 Article 4 ............................................................................................................... 66–77 15 Article 5 ............................................................................................................... 78 17 III. Information grouped under particular rights ........................................................... 79–139 -

394Ff57e71b60eca7e10344e37c4c9fc.Pdf

global history of the present Series editor | Nicholas Guyatt In the Global History of the Present series, historians address the upheavals in world history since 1989, as we have lurched from the Cold War to the War on Terror. Each book considers the unique story of an individual country or region, refuting grandiose claims of ‘the end of history’, and linking local narratives to international developments. Lively and accessible, these books are ideal introductions to the contemporary politics and history of a diverse range of countries. By bringing a historical perspective to recent debates and events, from democracy and terrorism to nationalism and globalization, the series challenges assumptions about the past and the present. Published Thabit A. J. Abdullah, Dictatorship, Imperialism and Chaos: Iraq since 1989 Timothy Cheek, Living with Reform: China since 1989 Alexander Dawson, First World Dreams: Mexico since 1989 Padraic Kenney, The Burdens of Freedom: Eastern Europe since 1989 Stephen Lovell, Destination in Doubt: Russia since 1989 Alejandra Bronfman, On the Move: The Caribbean since 1989 Nivedita Menon and Aditya Nigam, Power and Contestation: India since 1989 Hyung Gu Lynn, Bipolar Orders: The Two Koreas since 1989 Bryan McCann, The Throes of Democracy: Brazil since 1989 Mark LeVine, Impossible Peace: Israel/Palestine since 1989 James D. Le Sueur, Algeria since 1989: Between Terror and Democracy Kerem Öktem, Turkey since 1989: Angry Nation Nicholas Guyatt is assistant professor of history at Simon Fraser University in Canada. About the author Kerem Öktem is research fellow at the European Studies Centre, St Antony’s College, and teaches the politics of the Middle East at the Oriental Institute. -

Electoral Processes in the Mediterranean

Electoral Processes Electoral processes in the Mediterranean This chapter provides information on jority party if it does not manage to Gorazd Drevensek the results of the presidential and leg- obtain an absolute majority in the (New Slovenia Christian Appendices islative elections held between July Chamber. People’s Party, Christian Democrat) 0.9 - 2002 and June 2003. Jure Jurèek Cekuta 0.5 - Parties % Seats Participation: 71.3 % (1st round); 65.2 % (2nd round). Monaco Nationalist Party (PN, conservative) 51.8 35 Legislative elections 2003 Malta Labour Party (MLP, social democrat) 47.5 30 9th February 2003 Bosnia and Herzegovina Med. Previous elections: 1st and 8th Februa- Democratic Alternative (AD, ecologist) 0.7 - ry 1998 Federal parliamentary republic that Parliamentary monarchy with unicam- Participation: 96.2 %. became independent from Yugoslavia eral legislative: the National Council. in 1991, and is formed by two enti- The twenty-four seats of the chamber ties: the Bosnia and Herzegovina Fed- Slovenia are elected for a five-year term; sixteen eration, known as the Croat-Muslim Presidential elections by simple majority and eight through Federation, and the Srpska Republic. 302-303 proportional representation. The voters go to the polls to elect the 10th November 2002 Presidency and the forty-two mem- Previous elections: 24th November bers of the Chamber of Representa- Parties % Seats 1997 tives. Simultaneously, the two entities Union for Monaco (UPM) 58.5 21 Parliamentary republic that became elect their own legislative bodies and National Union for the Future of Monaco (UNAM) independent from Yugoslavia in 1991. the Srpska Republic elects its Presi- Union for the Monegasque Two rounds of elections are held to dent and Vice-President. -

Parolin V9 1..190

Citizenship in the Arab World IMISCOE International Migration, Integration and Social Cohesion in Europe The IMISCOE Network of Excellence unites over 500 researchers from European institutes specialising in studies of international migration, integration and social cohesion. The Network is funded by the Sixth Framework Programme of the European Commission on Research, Citizens and Governance in a Knowledge-Based Society. Since its foundation in 2004, IMISCOE has developed an integrated, multidisciplinary and globally comparative research project led by scholars from all branches of the economic and social sciences, the humanities and law. The Network both furthers existing studies and pioneers new research in migration as a discipline. Priority is also given to promoting innovative lines of inquiry key to European policymaking and governance. The IMISCOE-Amsterdam University Press Series was created to make the Network’s findings and results available to researchers, policymakers and practitioners, the media and other interested stakeholders. High-quality manuscripts authored by IMISCOE members and cooperating partners are published in one of four distinct series. IMISCOE Research advances sound empirical and theoretical scholarship addressing themes within IMISCOE’s mandated fields of study. IMISCOE Reports disseminates Network papers and presentations of a time-sensitive nature in book form. IMISCOE Dissertations presents select PhD monographs written by IMISCOE doctoral candidates. IMISCOE Textbooks produces manuals, handbooks and other didactic tools for instructors and students of migration studies. IMISCOE Policy Briefs and more information on the Network can be found at www.imiscoe.org. Citizenship in the Arab World Kin, Religion and Nation-State Gianluca P. Parolin IMISCOE Research This work builds on five years of onsite research into citizenship in the Arab world. -

AKDENİZ YÖS 2021 Application Procedure

AKDENİZ UNIVERSITY INTERNATIONAL STUDENT EXAM (AKDENİZ YÖS) AKDENİZ YÖS-2021 GUIDE TO APPLICATION PROCESS 1 CONTENTS 1. International Student Selection and Placement Calendar for Associate and Undergraduate Degree Programmes 2. Flow Diagram of the Application Process for AKDENİZ YÖS-2021 3. General Information, Basic Principles and Rules 4. Terms for Applications 5. Application Procedures 6. Payment of the Application Fee 7. Basic Learning Skills Test AKDENİZ YÖS Mission To provide a high standard of training for suitable international students through the application of a reliable, appropriate and modern selection and placement process which operates in accordance with our current internalization strategy. Vision To establish Akdeniz University as a world-class university which can provide a universally high standard of education to international students who can meet our selection criteria from any country in the world. 2 1. INTERNATIONAL STUDENT SELECTION AND PLACEMENT CALENDAR FOR ASSOCIATE AND UNDERGRADUATE DEGREE PROGRAMMES Online application System: yos.akdeniz.edu.tr Application Dates for the Akdeniz University International Student Exam (AKDENİZ YÖS) June 2-July 11, 2021 Deadline for Payment of the Application Fee July 13, 2021 (till 23.59 Tuesday) Date of the Akdeniz University International Student Admission July 28, 2021, Wednesday Exam (AKDENİZ YÖS-2021) at 14.00 (Turkish Time) Announcement on the Internet of the Results of the Akdeniz August 9, 2021 University International Student Exam (AKDENİZ YÖS) Objections to the Result -

Who's Who in Politics in Turkey

WHO’S WHO IN POLITICS IN TURKEY Sarıdemir Mah. Ragıp Gümüşpala Cad. No: 10 34134 Eminönü/İstanbul Tel: (0212) 522 02 02 - Faks: (0212) 513 54 00 www.tarihvakfi.org.tr - [email protected] © Tarih Vakfı Yayınları, 2019 WHO’S WHO IN POLITICS IN TURKEY PROJECT Project Coordinators İsmet Akça, Barış Alp Özden Editors İsmet Akça, Barış Alp Özden Authors Süreyya Algül, Aslı Aydemir, Gökhan Demir, Ali Yalçın Göymen, Erhan Keleşoğlu, Canan Özbey, Baran Alp Uncu Translation Bilge Güler Proofreading in English Mark David Wyers Book Design Aşkın Yücel Seçkin Cover Design Aşkın Yücel Seçkin Printing Yıkılmazlar Basın Yayın Prom. ve Kağıt San. Tic. Ltd. Şti. Evren Mahallesi, Gülbahar Cd. 62/C, 34212 Bağcılar/İstanbull Tel: (0212) 630 64 73 Registered Publisher: 12102 Registered Printer: 11965 First Edition: İstanbul, 2019 ISBN Who’s Who in Politics in Turkey Project has been carried out with the coordination by the History Foundation and the contribution of Heinrich Böll Foundation Turkey Representation. WHO’S WHO IN POLITICS IN TURKEY —EDITORS İSMET AKÇA - BARIŞ ALP ÖZDEN AUTHORS SÜREYYA ALGÜL - ASLI AYDEMİR - GÖKHAN DEMİR ALİ YALÇIN GÖYMEN - ERHAN KELEŞOĞLU CANAN ÖZBEY - BARAN ALP UNCU TARİH VAKFI YAYINLARI Table of Contents i Foreword 1 Abdi İpekçi 3 Abdülkadir Aksu 6 Abdullah Çatlı 8 Abdullah Gül 11 Abdullah Öcalan 14 Abdüllatif Şener 16 Adnan Menderes 19 Ahmet Altan 21 Ahmet Davutoğlu 24 Ahmet Necdet Sezer 26 Ahmet Şık 28 Ahmet Taner Kışlalı 30 Ahmet Türk 32 Akın Birdal 34 Alaattin Çakıcı 36 Ali Babacan 38 Alparslan Türkeş 41 Arzu Çerkezoğlu -

Crisis in Turkey: Just Another Bump on the Road to Europe?

Occasional Paper June 2007 n°67 Walter Posch Crisis in Turkey: just another bump on the road to Europe? published by the European Union Institute for Security Studies 43 avenue du Président Wilson F-75775 Paris cedex 16 phone: + 33 (0) 1 56 89 19 30 fax: + 33 (0) 1 56 89 19 31 e-mail: [email protected] www.iss.europa.eu In January 2002 the EU Institute for Security Studies (EUISS) was created as a Paris- based autonomous agency of the European Union. Following an EU Council Joint Action of 20 July 2001, modified by the Joint Action of 21 December 2006, it is now an integral part of the new structures that will support the further development of the CFSP/ESDP. The Institute’s core mission is to provide analyses and recommendations that can be of use and relevance to the formulation of EU policies. In carrying out that mission, it also acts as an interface between experts and decision-makers at all levels. Occasional Papers are essays or reports that the Institute considers should be made avail- able as a contribution to the debate on topical issues relevant to European security. They may be based on work carried out by researchers granted awards by the EUISS, on contri- butions prepared by external experts, and on collective research projects or other activities organised by (or with the support of) the Institute. They reflect the views of their authors, not those of the Institute. Publication of Occasional Papers will be announced in the EUISS Newsletter and they will be available on request in the language - either English or French - used by authors. -

THE RIGHT to CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTION in EUROPE: a Review of the Current Situation

THE RIGHT TO CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTION IN EUROPE: A Review of the Current Situation Quaker Council for European Affairs Preface Aware of the fact that conscientious objectors are still treated harshly in some European countries and that the right to conscientious objection is not even recognized in all the member states of the Council of Europe, the Quaker Council for European Affairs commissioned this report to highlight the problems which still remain in Europe with regard to the right to conscientious objection to military service. This report provides an overview of the current situation in Europe. In recent years many developments have taken place with regard to conscription and conscientious objection. Several European countries have suspended conscription although by 2005 most European countries still maintain conscription and most European young men are still liable to perform military service. In many countries, particularly in Eastern Europe, the Balkans and the former Soviet Union, both legal regulations on the recognition of the right to conscientious objection and actual practice are changing quickly. In other European countries, the right to conscientious objection is still not recognized fully or at all and governments persist in harsh treatment of conscientious objectors. Although there is a wealth of information available about conscription and conscientious objection in some countries, surprisingly little is known about others. Moreover, there is no recent comparative survey on conscientious objection in easily accessible format. The last survey of this kind was published in 1998 by War Resisters' International ('Refusing to bear arms - a world survey of conscription and conscientious objection to military service'), which answered the need of many organisations working on issues of conscription and conscientious objection. -

Analysing the Impact of the Turkish Emergency Legislation on the Kurdish Case

The exception within the rule: analysing the impact of the Turkish emergency legislation on the Kurdish case. Supervisor: Kathleen Cavanaugh Candidate: Carlotta Giordani A.Y. 2012/2013 Supervisor: Kathleen Cavanaugh Candidate: Carlotta Giordani Second Semester University: NUI Galway The exception within the law: analysing the impact of the Turkish emergency legislation on the Kurdish case. ABSTRACT Starting from an historical and anthropological overview, necessary to understand the deep roots of the conflict between Turks and Kurds, the object of this study focuses on why and how the use of the State of Emergency and the related legislation implemented by Turkey, impacted the so-called Kurdish Question. The investigation conducted along this work is aimed at clarifying the consequences related to the Emergency Regulation phenomenon in this particular context. The definition of Kurds and Kurdistan raises several matters: Kurds are often considered as the biggest stateless population, a heterogeneous group geographically dislocated with a shared cultural identity. The analysis of the legislation implemented by the Turkish state started after the proclamation of the Republic of Turkey, in 1923: the constant use of the repressive measures can be considered as a reaction to the Sevrès Paranoia , the symbol of the Turkish fear of the state territory disintegration. The social changes occurred after the 1960 military Coup d’Etat definitely opened to the birth of the PKK and to the political use of the law, legitimized by the new constitution and made concrete by the 1971 Martial Act n. 1402. This juridical system and the collusion between the military and the civilian, brought to the 1980 Coup d’Etat, the draft of a new constitution (amended but still in force), the 1983 State of Emergency Law (N.2935) and to the creation of a the OHAL Region: the Kurdish areas since that moment were under the jurisdiction of a special emergency governor, so that making even crueller the PKK reactions.