Transcript-Privacy, Confidentiality & Security Meeting-September 14, 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategic Horizons

America in Africa Securing U.S. Interests and Promoting a Continent’s Development J. Peter Pham COVER PHOTOS (clockwise): Shell Oil fields in Nigeria’s Delta region, “flaring” natural gas. Photo © by Robert Grossman. Africaphotos.com. Used by Permission. U.S. Navy Cmdr. Paul Vandenberg, right, an engineer with Naval Mobilie Construction Battalion Seven, greets Abdi Reshid Mohamed Omer, center, the head of Ethiopia’s Mines and Energy Department, and Alemayehu Mekonin, a water engineer, at a waste water treatment facility in Gode, Ethiopia, March 31, 2006. Vandenberg is doing preliminary research on behalf of Combined Joint Task Force Horn of Africa, which is interested in aiding a construction project to add capacity to the area’s water treatment capabilities. Photo © by Photographer’s Mate 2nd Class Roger S. Duncan, U.S. Navy. Photo courtesy of www.usaid.gov. The International Republican Institute honors First Lady and Liberian President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf at IRI’s Freedom Award dinner on September 21, 2006. Photo courtesy of the International Republican Institute, www.iri.org. America in Africa: Securing U.S. Interests and Promoting a Continent’s Development A Framework for Increased U.S. Strategic Engagement in Africa by J. Peter Pham Nelson Institute for International and Public Affairs at James Madison University strives to meet both the educational needs of its students in a changing world and a public institution of higher education’s responsibility to respond to the “real world” challenges by supporting scholarship in the social sciences and humanities and providing an environment that will encourage interdisciplinary discourse on contemporary public concerns. -

CLASS of 1955 50Th REUNION Martha Haskell Baird

BENNINGTON COLLEGE Class of 1955 50 TH REUNION Class of 1955 Elizabeth Green Appleton Ethelyn Blinder Honig Mancia Schwartz Propp Alan Arkin Martha T. Howell Toby Carr Rafelson Sheila Gallagher Arnaboldi Maryan Forbes Hurtt Gloria Haines Root Jean Fager Arnold Barbara Shivitz Isaacs Carol Rubenstein Lawrence Arrick Lenore Janis Shaila Rubin Martha Haskell Baird Barbara Kelly Johnson Marion Krapowicz Safford Joyce Orgel Basche Vija Peterson Johnson Susan Mack Saril Jane Simpson Bauer Dorothea Booth Katz Pamela Pollard Saxton* Sibyl Totah Belmont* Rosemary Frost Khan Stephanie Schecht Schottin Ruth Greenwald Beschloss Miriam Hermanos Knapp Faith Bancroft Schrader Betty Smith Bishop Ellen Thomas Lacourt Barbara Goldman Schulman Sally Teitelbaum Blum Fern Galane Lenter Donna Bear Scott Gertrude Scheff Brown Elizabeth Lester Jacqueline Klein Segal Margaret Garry Buckley* Evelyn Jerome Lindsay Ann Shaff Eileen Gates Carrier* Sandra L. Stewart Little* Stella Spanoudaki Sichel Nancy M. Connable Selina F. Little Julie Cummings Siff Martha Dagnall Terry Monash Littwin* Ruth Fidel Silverman Alice Glantz Daniel Vanni Mechau Lowdenslager Jane Ludwig Simon Beverly Davenport* Janet Burke Mann Sally Smith* Ellen Huddleson de la Torre Joan Morris Manning Nancy Lee Smith Suzanne Thomas Dolloff Barbara Silver Marcus* Irene Reik Soffer Winifred Graham Downsbrough* Mary Kent Marshall* Betty Ungerleider Steiner Joan Geiger Doyle Nancy Baird Matthews Barbara Suchman Nancy Wharton Duryea* Jane Uhler McDonough Latifah (Irene) Ryan Taormina Sheila Paperny Ellis -

My Son, the Paper

Inspiring Magazines that Died Before their Time. OU may remember some of these inspiring publications if you are one of us old farts, Yor maybe you never even heard of any of them. Some of these titles go way back, over a hundred years or more, and a few are as recent as this year. All of these magazines came and went, often without notice. Lots of them ran for years before they folded, and a few only lasted for just a couple of issues. Two came out for just their first issue, and one never made it past the printing press. But all of these publications were launched with a goal of continu - ing until the end of time. In addition to my collection, we have a good number of publications from Richard Stanley and Ed Gold; we shall hear from them as well as yours truly as they present a few of their choices. But first, I’d like to set the stage: Most of what you’ll see are publications—magazines, tabloids, and boxed editions—period - icals created for designers, illustrators, photographers, and creatives in all fields of the graphic arts. We also have general and special-interest magazines published for adults with discriminating tastes—designed and edited by creative professionals who earned fame for their award-winning work. We have volumes by Milton Glaser, Seymour Chwast, Herb Lubalin, Andy Warhol (before he took up pop art), David Carson, Roger Black, Henry Wolf, Alexey Brodovitch… and the list of impressive names goes on. During the 1960s, 70s, and 80s we saw a boom in magazine development: New publica - tions were launched, existing ones spun off siblings, and many successful publications were redesigned and expanded. -

April 2009 Steven Brodner

DIALOGUE Steven Heller in conversation steven brodner caricaturist The Bush years were a boom time for Steve Brodner. A satirical illustrator known for stun- ning caricatures, he was blessed with an incredible cast of corrupt and venal characters as targets. Brodner has been turning up the graphic heat since the 1990s, and the Age of W didn’t stand a chance. He is one of the best of what might be called the “second generation” of American graphic commentators, the first being David Levine, Edward Sorel, Jules Feiffer, and Robert Grossman. Brodner has created satire for more than 30 years, initially channeling the great Thomas Nast, then finding his own expressive style. The list of magazines and newspapers to which he’s contrib- uted sly commentary on presidential elections, controversial subjects, and outdoorsy events is long: Harper’s, National Lampoon, Sports Illustrated, Playboy, Spy, Esquire, The Progressive, The Village Voice, The Washington Post, Texas Monthly, Philadelphia magazine—it goes on. He has been the editor of The Nation’s cartoon feature, “Comix Nation,” and throughout the 2008 election season, he talked as he drew for The New Yorker’s “The Naked Campaign” videos. In 2008, an exhibition of his political work was mounted at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. We caught up with Brodner after the election to talk about the art and politics of caricature, the “of course” mo- ment, and raging against the machine. STEVEN HELLER have the visual and literal messages blend so Print contributing editor, author, co-chair of the Designer as well that you don’t see a difference. -

The Burden of Diabetes

NYUTHE MAGAZINE OF NEW YORK UNIVERSIPHTY SCHOOL OF MEDICINEYSICIAFALL 2011N volume 63 • No. THE 1 BURDEN OF DIABETES THE OBESITY PANDEMIC AVOIDING AMPUTATION PREVENTION PROSPECTS THERAPIES ON THE HORIZON PLUS Q&A WITH THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD TEN YEARS AFTER 9-11 THE HIGH COST OF ADDICTION Help Us Make Dreams Come True EVERY ASPIRING PHYSICIAN DREAMS OF THE DAY SOMEONE WILL MAKE A GIFT ONLINE CALL HIM OR HEr “DOCTor” FOR THE FIRST TIME. But getting there Please visit www.nyu.edu/alumni. takes a lot more than hard work and dedication—it takes resources. By contributing to the NYU School of Medicine Alumni Campaign, you help To discuss special ensure that our next generation of physicians will have access to the best giving opportunities, teaching and research, along with a competitive financial assistance package. call Anthony J. Grieco, MD, Associate Dean for Alumni Relations, When you make a gift, you help us guarantee that all of our students will at 212.263.5390. have the means to complete our rigorous education. One day, you may even have the privilege of addressing them yourself as “Doctor.” Thank you for your generosity. THE MAGAZINE OF NEW YORK UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MEDICINE FALL 2011 VOLUME 63 NO. NYU PHYSICIAN 1 New York University D EPARTMENTS Martin Lipton, Esq. Chairman, Board of Trustees 02 Letter from the Dean John Sexton President 03 S upport Q & A with Ken Langone Robert Berne What it takes to raise $1 billion Executive Vice President for Health in record time 04 News from Medicine NYU Langone• Medical Center Can Obesity Be Linked to Diabetes? What Does the Nose Know? Kenneth G. -

Arts and Science Message from the Dean

New York University Bulletin 2007-2009 Graduate School of Arts and Science http://gsas.nyu.edu Message from the Dean he Graduate School of Arts and Science is an advocate for advanced inquiry and Tcreativity. As such, we prize the graduate student who can combine curiosity, strong capabilities, and a mind drawn to the highest challenges of history or economics or neural science or the interdisciplinary exploration of social thought or any other big field. Our bulletin tells faculty, students, and others about our intellectual vision and the programs and people that embody that vision. Our offerings demonstrate that graduate schools are the academic nerve center of the contemporary university. Here, ground-breaking discoveries are made, ideas (old and new) investigated, and the next generation of scholars, researchers, thinkers, and faculty educated. New York University has been a pioneer in graduate education. In 1866, it became the second university in the United States to offer an earned doctorate. In 1886, the Graduate School of Arts and Science opened to a wide variety of able students. Today, we house 53 programs that offer doctoral and master’s degrees and certificates. They balance disciplinary and interdisciplinary work. We enroll over 4,700 students each year. I hope that we stay true to an experimental and fluid spirit. In order to do so, we call on the abundant creative energies of New York, that greatest of global cities, and of our faculty, which will grow by 25 percent by the end of this decade. Together, faculty and the students who choose to work with them are the brains that power our school. -

The Historical Trauma and Resilience of Individuals of Mexican Ancestry in the United States: a Scoping Literature Review and Emerging Conceptual Framework

genealogy Review The Historical Trauma and Resilience of Individuals of Mexican Ancestry in the United States: A Scoping Literature Review and Emerging Conceptual Framework Araceli Orozco-Figueroa School of Social Work, University of Washington, 4101 15 Avenue NE Seattle, WA 98105-6250, USA; [email protected] Abstract: Recently, Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color (BIPOC) have encountered an escalation in adverse social conditions and trauma events in the United States. For individuals of Mexican ancestry in the United States (IMA-US), these recent events represent the latest chapter in their history of adversity: a history that can help us understand their social and health disparities. This paper utilized a scoping review to provide a historical and interdisciplinary perspective on discussions of mental health and substance use disorders relevant to IMA-US. The scoping review process yielded 16 peer reviewed sources from various disciplines, published from 1998 through 2018. Major themes included historically traumatic events, inter-generational responses to historical trauma, and vehicles of transmission of trauma narratives. Recommendations for healing from historical and contemporary oppression are discussed. This review expands the clinical baseline knowledge relevant to the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of contemporary traumatic exposures for IMA-US. Keywords: scoping review; Mexican and Mexican-Indigenous; historical trauma and posttrau- Citation: Orozco-Figueroa, Araceli. matic growth framework (HT-PGF); historical trauma events (HTEs); behavioral health; resilience; 2021. The Historical Trauma and institutional mistrust; health-advantage; wellness; stronger together Resilience of Individuals of Mexican Ancestry in the United States: A Scoping Literature Review and Emerging Conceptual Framework. 1. Introduction Genealogy 5: 32. -

Fall 2017 Fall 2017

THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE OF NYU SCHOOL OF MEDICINE OF NYU SCHOOL OF MEDICINE FALL 2017 FALL 2017 THE BEST OF HUMANITY From disaster zones to local clinics, doctors THE BEST OF like Hernando Garzon ’88 HUMANITY are there to help. From disaster zones to local clinics, doctors like Elizabeth Lutas ’76 are there to help. SUPPORT OUR STUDENTS AND CREATE YOUR OWN LEGACY. Your gift of $30,000 (payable over up to three years) will be acknowledged with a named dorm room in Vilcek Hall. Planned gifts may qualify as well. One hundred percent of your contribution will support scholarships for NYU School of Medicine students. LEARN MORE: Visit nyulangone.org/give/vilcek-hall-campaign, or contact Diana Robertson at 212-404-3510 or [email protected]. DEAN’S MESSAGE What Sets Us Apart Even after a decade of tremendous progress, the momentum at NYU Langone Health continues to grow. As the following accolades and statistics make clear, our mission to serve, teach, and discover remains steadfast and strong. Our innovative approach to medical training Of course, these numbers tell only part of continues to attract the most talented aspiring the story. The less heralded engine of our doctors, and our matriculating students rate success—and the critical if unquantifiable among the elite in GPA and MCAT scores. In reason the best still lies ahead—is the unique fact, NYU School of Medicine has rocketed in blend of values, talent, and dynamism that the rankings from #34 to #12 according to the generations of students, faculty, and staff U.S. -

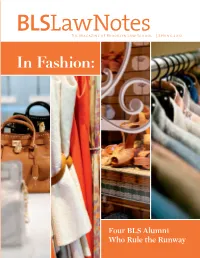

Spring 2012 Address Service Requested BLS Lawnotes Spring Spring

250 Joralemon Street, Brooklyn, New York 11201 BLSLawNotesThe Magazine of Brooklyn Law School | Spring 2012 address service requested BLS LawNotes Spring 2012 In Fashion: Upcoming Events MAY 10 CHICAGO ALUMNI RECEPTION JUNE 13 ALUMNI RECEPTION Hosted by Geoffrey Richards ’95 Lori Bookstein Fine Art Gallery The Chicago Club Chelsea MAY 17 CLASS REUNIONS AUGUST 12 CONVOCATION For the classes of 1952, 1957, 1962, 1967, 1972, 1977, 1982, 1987, 1992, 1997, 2002, and 2007 New York Public Library AUGUST 20 FALL SEMESTER CLASSES BEGIN SEPTEMBER 28 THEORY PRACTICE SEMINAR MAY 21 SUMMER SESSION CLASSES BEGIN Writing the Master Narrative for U.S. Health Policy In celebration of the Center for Health, Science JUNE 1 COMMENCEMENT and Public Policy’s 10th Anniversary speaker: Honorable Carol Bagley Amon, Chief Judge, United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York OCTOBER 11–12 SYMPOSIUM Avery Fisher Hall Forensic Authorship Identification Workshop Sponsored by the Center for Law, Language, and Cognition and the Journal of Law and Policy JUNE 7 RECENT GRADUATE RECEPTION Brooklyn Brewery Williamsburg NOVEMBER 2 ALUMNI ASSOCIATION LUNCHEON The Plaza Hotel JUNE 12 BARRY L. ZARETSKY ROUNDTABLE DINNER AND DISCUSSION Debtors in Play: Insider Trading, Claims For more information about events and dates, please visit Four BLS Alumni Regulation, and Safe Harbors in Chapter 11 our Web site at www.brooklaw.edu/NewsAndEvents. Who Rule the Runway jewelry. Food vendors include Cheeky BLSLawNotes Booklyn’s Finest Sandwiches, Joe, the Art of Coffee, Vol. 17, No. 1 Robicelli’s cupcakes, and Park Slope fro-yo fave Culture. The entertainment Editor-in-Chief Graphic Design space includes a roller-skating party on Linda S. -

How About Never Is Never Good for You?

Henry Holt and Company, LLC Publishers since 1866 175 Fifth Avenue New York, New York 10010 www .henryholt .com Henry Holt® and ® are registered trademarks of Henry Holt and Company, LLC. Copyright © 2014 by Bob Mankoff All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Mankoff , Robert. How about never— is never good for you? : my life in cartoons / Bob Mankoff . — First edition. pages cm ISBN 978- 0- 8050- 9590- 6 (hardback)—ISBN 978- 0- 8050- 9591- 3 (electronic book) 1. Mankoff , Robert. 2. Cartoonists— United States— Biography. 3. Periodical editors— United States— Biography. 4. New Yorker (New York, N.Y. : 1925) I. Title. NC1429.M358A2 2014 741.5′6973—dc23 [B] 2013021129 Henry Holt books are available for special promotions and premiums. For details contact: Director, Special Markets. First Edition 2014 Designed by Toshiya Masuda Printed in the United States of America 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 020-55629_ch00_7P.indd vi 1/23/14 6:11 AM Dedicated to everyone who has ever done a cartoon for Th e New Yorker Charles Addams, John Agee, Alain, Constantin Alajalov, Edward H. Allison, Gideon Amichay, C. W. An- derson, Geroge Annand, Robb Armstrong, Ed Arno, Peter Arno, Andrea Arroyo, Jose Arroyo, Jose Aruego, Niculae Asciu, Van Ass, T. K. Atherton, Aaron Bacall, Tom Bachtell, Peggy Bacon, Howard Baer, Bruce Bairnsfather, Ernest Hamlin Baker, Cyrus Baldridge, Perry Barlow, Bob Barnes, H. Barnes, Charles Bar- sotti, Donna Barstow, Ralph Barton, H. M. Bateman, Ross Bateup, Roland Baum, Glen Baxter, Ben Hur Baz, Alex Beam, Kate Beaton, Frank Beaven, Ludwig Bemelmans, Nora Benjamin, Bill Berg, Erik Berg- strom, Mike Berry, François Berthoud, Daniel Beyer, Michael Biddle, Reginald Birch, Kenneth Bird, Abe Birnbaum, Mahlon Blaine, Harry Bliss, Barry Blitt, A. -

Download a PDF Copy

2016 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 ANNUAL REPORT MEMORIAL SLOAN KETTERINGMEMORIAL CANCER SLOAN CENTER GENERAL INFORMATION 212.639.2000 1275 YORK AVENUE MAKE AN APPOINTMENT NEW YORK, NY 10065 800.525.2225 VISIT US ONLINE WWW.MSKCC.ORG FACEBOOK.COM/SLOANKETTERING TWITTER.COM/SLOAN_KETTERING YOUTUBE.COM/MSKCC INSTAGRAM.COM/SLOANKETTERING WWW.MSKCC.ORG/ANNUALREPORT 2016: A YEAR OF I N N O VAT I O N I N N O VAT I O N INNOVATION Cancer will never have a one-size-fits-all solution. This intricate, challenging, ever- shifting disease is nothing if not complex. And though it’s often described with a single word — cancer — there are actually more than 400 distinct types, each with its own unique characteristics and vulnerabilities. The doctors, nurses, and scientists at Memorial around the world. We unearthed new answers Sloan Kettering are experts at matching cancer’s to old questions about fundamental biological complexity with an equally nuanced understanding processes. We tested and perfected novel of all its varieties. We strive to choose the optimal technologies and brought them directly to treatment for every patient, and we’re always patients. We led the development of drugs searching for better ways to do so. for cancers that haven’t seen new therapies in decades — and brought them through to FDA We address cancer’s intricacy from every approval. And we opened new locations and possible angle, both by thinking creatively refreshed existing ones to better accommodate and by utilizing the latest, most pioneering the needs of our unique patients. advances in technology, basic and clinical research, treatment, and patient care. -

Theory and Interpretation of Narrative James Phelan and Peter J

Theory and Interpretation of Narrative James Phelan and Peter J. Rabinowitz, Series Editors Acknowledgments | ii the real, the true, THE REAL, THE TRUE, AND THE TOLD Postmodern Historical Narrative and the Ethics of Representation ERIC L. BERLATSKY theTHE OHIO ST ATE UNIVERtoldSITY PRESS • COLUMBUS For Jennie, Katie, and Julia Copyright © 2011 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Berlatsky, Eric L., 1972– The real, the true, and the told : postmodern historical narrative and the ethics of representa- tion / Eric L. Berlatsky. p. cm. — (Theory and interpretation of narrative series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1153-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1153-4 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-9254-9 (cd) 1. Historical fiction—History and criticism. 2. Postmodernism (Literature) 3. History—Phi- losophy. 4. Historiography. 5. Woolf, Virginia, 1882–1941—Criticism and interpretation. 6. Swift, Graham, 1949—Criticism and interpretation. 7. Rushdie, Salman—Criticism and interpretation. 8. Spiegelman, Art—Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. II. Series: Theory and interpretation of narrative series. PN3441.B47 2011 809.3’81—dc22 2010033740 This book is available in the following editions Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1153-3) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9254-9 Cover design by Jeffrey Smith. Text design by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe. Type set in Adobe Minion Pro. Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992.