Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and the Fate of the Confederacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Follow in Lincoln's Footsteps in Virginia

FOLLOW IN LINCOLN’S FOOTSTEPS IN VIRGINIA A 5 Day tour of Virginia that follows in Lincoln’s footsteps as he traveled through Central Virginia. Day One • Begin your journey at the Winchester-Frederick County Visitor Center housing the Civil War Orientation Center for the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District. Become familiar with the onsite interpretations that walk visitors through the stages of the local battles. • Travel to Stonewall Jackson’s Headquarters. Located in a quiet residential area, this Victorian house is where Jackson spent the winter of 1861-62 and planned his famous Valley Campaign. • Enjoy lunch at The Wayside Inn – serving travelers since 1797, meals are served in eight antique filled rooms and feature authentic Colonial favorites. During the Civil War, soldiers from both the North and South frequented the Wayside Inn in search of refuge and friendship. Serving both sides in this devastating conflict, the Inn offered comfort to all who came and thus was spared the ravages of the war, even though Stonewall Jackson’s famous Valley Campaign swept past only a few miles away. • Tour Belle Grove Plantation. Civil War activity here culminated in the Battle of Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864 when Gen. Sheridan’s counterattack ended the Valley Campaign in favor of the Northern forces. The mansion served as Union headquarters. • Continue to Lexington where we’ll overnight and enjoy dinner in a local restaurant. Day Two • Meet our guide in Lexington and tour the Virginia Military Institute (VMI). The VMI Museum presents a history of the Institute and the nation as told through the lives and services of VMI Alumni and faculty. -

Historic Structure Report: the Stone House

Historic Structure Report The Stone House (Misnamed the Salty Dog Saloon) Opposite C & O Canal Lock 33 Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park Historical Data Harpers Ferry National Historical Park W.Va.–Va.–Md. By Edward D. Smith Denver Service Center National Capital Team National Park Service United States Department Of The Interior Denver, Colorado March 25, 1980 Original Version 1980 Electronic/PDF Version 2012 Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park 1850 Dual Highway, Suite 100 Hagerstown, MD 21740 ii Preface to the 2012 Edition The 2012 edition was prepared as a volunteer project for publication as a pdf document available to the public on the National Park Service history website. See: (http://www.nps.gov/history/history/park_histories/index.htm#choh). Only stylistic, grammatical, and format changes were made to the core text, but several footnotes were added and identified as mine by including “—kg” at the end. These all include new information or research that supplements the original text. Also additional images, including the Historic American Buildings Survey’s measured drawing, have been added to the Illustrations. The document is formatted with a gutter to facilitate two-sided printing and binding. The page number is at the bottom of the initial pages of major sections and on the upper out- side corner of all other pages. Karen M. Gray, Ph.D. Volunteer, Headquarters Library C&O Canal National Historical Park Hagerstown, MD June 19, 2012 iii Preface to the 1980 Edition The abandoned stone house at the base of Maryland Heights opposite Canal Lock 33 is perhaps the most talked-about house along the canal. -

WA-II-035 Ferry Hill Plantation (Ferry Hill Inn, Ferry Hill Place, Blackford's Plantation)

WA-II-035 Ferry Hill Plantation (Ferry Hill Inn, Ferry Hill Place, Blackford's Plantation) Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 03-12-2004 2-2.--0 z,e34-32-7 Copy 2 WA-II-035 MARYLAND HISTORICAL TRUST WORKSHEET NOMINATION FORM for the NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES, NATIONAL PARKS SERVICE Ferry Hill Inn AND/QR HISTORIC: f2.. LOCATtO_•N~.· _..__ _.._..._..._ _______ ~--~~--~-~----------'-~---"'"-'I STREET ANC' NUMBER: Maryland Route 34 at the Potomac River CITY OR TOWN: Sharpsburg CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS ACCESSIBLE (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC z Yes: 0 District ~ Building 0 Public Public Acquisition: ~ Occupied 0 .8) Restricted D Site 0 Structure 1¥1 Private 0 In Process D Unoccupied Unrestricted 0 Object O Both 0 Being Considered 0 Preservation work D in progress D No PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) 0 Agricultural 0 Government 0 Park 0 Transportation 0 Comments 0 Commercial 0 Industrial 0 Private Residence ~ Other (Specify) 0 Educational 0 Military 0 Religious inn/restaurant 0 Entertainment 0 Museum 0 Scientific z ti(. -

Brochure Design by Communication Design, Inc., Richmond, VA 8267 Main Street Destinations Like Chestertown, Port Deposit, Bel Air, Ellicott City, WASHINGTON, D.C

BALTIMOREST. P . R ESI . Druid Hill Park . 1 . D UL ST . E ST NT PENNSYLV ANIA PA WATER ST. ARD ST S VERT ST AW T 25 45 147 . EUT SAINT HOW HOPKINS PL LOMBARD ST. CHARLES ST CAL SOUTH ST MARKET PL M ASON AND DIXON LINE S . 83 U Y ST 273 PRATTST. COMMERCE ST GA S NORTH AVE. 1 Q Emmitsburg Greenmount 45 ST. U Cemetery FAWN E 1 H . T S A T H EASTERN AVE. N G USS Constellation I Union Mills L N SHARP ST CONWAYST. A Manchester R Taneytown FLEET ST. AY I Washington Monument/ Camden INNER V 1 E Mt. Vernon Place 97 30 25 95 Station R MONUMENT ST. BROADW HARBOR President Maryland . Street 27 Station LANCASTER ST. Historical Society . ORLEANS ST. ERT ST T . S Y 222 40 LV A Thurmont G Church Home CA Susquehanna Mt. Clare and Hospital KEY HWY Battle Monument 140 BALTIMORE RIOT TRAIL State Park Port Deposit ELKTON Mansion BALTIMORE ST. CHARLES ST (1.6-mile walking tour) 7 LOMBARD ST. Federal Hill James Archer L 77 Birthplace A PRATT ST. Middleburg Patterson P I Old Frederick Road D 40 R Park 138 U M (Loy’s Station) . EASTERN AVE. E R CONWAY ST. D V Mt. Clare Station/ B 137 Hereford CECIL RD ST USS O T. S I VE. FLEET ST. T 84 24 1 A B&O Railroad Museum WA O K TS RIC Constellation Union Bridge N R DE Catoctin S Abbott F 7 E HO FR T. WESTMINSTER A 155 L Monkton Station Furnance LIGH Iron Works L T (Multiple Trail Sites) S 155 RD 327 462 S 31 BUS A Y M 1 Federal O R A E K I Havre de Grace Rodgers R Hill N R S D T 22 Tavern Perryville E 395 BALTIMORE HARFORD H V K E Community Park T I Y 75 Lewistown H New Windsor W Bel Air Court House R R Y 140 30 25 45 146 SUSQUEHANNA O K N BUS FLATS L F 1 OR ABERDEEN E T A VE. -

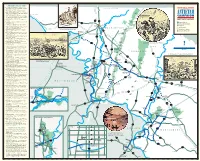

Antietam Map Side

★ ANTIETAM CAMPAIGN SITES★ ★ Leesburg (Loudoun Museum) – Antietam Campaign To ur begins here, where Lee rested the Army of Northern MASON/DIXON LINE Virginia before invading Maryland. ★ Mile Hill – A surprise attack led by Confederate Col. Thomas Munford on Sept. 2, 1862, routed Federal forces. ★ White’s Ferry (C&O Canal NHP) – A major part of Lee’s army forded the Potomac River two miles north of this mod- ern ferry crossing, at White’s Ford. To Cumberland, Md. ★ White’s Ford (C&O Canal NHP) – Here the major part of the Army of Northern Virginia forded the Potomac River into Maryland on September 5-6, 1862, while a Confederate band played “Maryland! My Maryland!” ★ Poolesville – Site of cavalry skirmishes on September 5 & 8, 1862. 81 11 ★ Beallsville – A running cavalry fight passed through town Campaign Driving Route on September 9, 1862. 40 ★ Barnesville – On September 9, 1862, opposing cavalry Alternate Campaign Driving Route units chased each other through town several times. Rose Hill HAGERSTOWN Campaign Site ★ Comus (Mt. Ephraim Crossroads) – Confederate cavalry Cemetery fought a successful rearguard action here, September 9-11, Other Civil War Site 1862, to protect the infantry at Frederick. The German Reformed Church in Keedysville W ASHINGTON ★ Sugarloaf Mountain – At different times, Union and was used as a hospital after the battle. National, State or County Park Confederate signalmen atop the mountain watched the 40 I L InformationInformation or Welcome Center opposing army. Williamsport R A T ★ Monocacy Aqueduct (C&O Canal NHP) – Confederate (C&O Canal NHP) troops tried and failed to destroy or damage the aqueduct South Mountain N on September 4 & 9, 1862. -

Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign

Civil War Book Review Spring 2009 Article 17 Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign Judkin Browning Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Browning, Judkin (2009) "Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 11 : Iss. 2 . Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol11/iss2/17 Browning: Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign Review Browning, Judkin Spring 2009 Cozzens, Peter Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson’s Valley Campaign. University of North Carolina Press, $35.00 hardcover ISBN 9780807832006 The Shenandoah Campaign and Stonewall Jackson In his fascinating monograph, Peter Cozzens, an independent scholar and author of The Darkest Days of the War: The Battles of Iuka and Corinth (1997), sets out to paint a balanced portrait of the 1862 Shenandoah Valley campaign and offer a corrective to previous one-sided or myth-enshrouded historical interpretations. Cozzens points out that most histories of the campaign tell the story exclusively from the perspective of Stonewall Jackson’s army, neglecting to seriously analyze the decision making process on the Union side, thereby simply portraying the Union generals as the inept foils to Jackson’s genius. Cozzens skillfully balances the accounts, looking behind the scenes at the Union moves and motives as well as Jackson’s. As a result, some historical characters have their reputations rehabilitated, while others who receive deserved censure, often for the first time. After a succinct and useful environmental and geographical overview of the Shenandoah region, Cozzens begins his narrative with the Confederate army during Jackson’s early miserable forays into the western Virginia Mountains in the winter of 1861, where he made unwise strategic decisions and ordered foolish assaults on canal dams near the Potomac River that accomplished nothing. -

1860 Stephen Douglas John Breckinridge Abraham Lincoln John

1860 Circle the winner ______________, Stephen Douglas , Northern Democrat __________________John Breckinridge , Abraham________________ Lincoln , ____________John Bell Southern Democrat Republican Constitutional Union Platform: Platform: Platform: Platform: • enforce the Fugitive Slave • unrestricted • no expansion of slavery • preserve the Union Act expansion of slavery • protective tariffs • allow territories to vote on • annexation of Cuba • internal improvements practice of slavery CRITTENDEN COMPROMISE, December 1860 • In an attempt to ____________________________________________________,keep the nation together Senator John J. Crittenden proposed a compromise that ___________________________________________________offered concessions to the South including: • ________________________________Guaranteeing the existence of slavery in the South • Extending the ______________________________Missouri Compromise to the western territories • The compromise _______________failed • December 20, 1860 - _______________________South Carolina voted to secede from the Union • Many Southerners in ______________________________________President Buchanan’s cabinet resigned and his administration fell apart. • When Buchanan became president, there were _______32 states in the Union. • When he left, there were ______.25 Jefferson Davis, 1861 CONFEDERATE STATES OF AMERICA • ______________________________________________________________________Florida, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas joined South Carolina in voting to secede. • Together -

The Battle of Antietam U.S

National Park Service The Battle of Antietam U.S. Department of the Interior Antietam National Battlefield P. O. Box 158 Sharpsburg, MD 21782 Dawn approached slowly through the fog on September 17, 1862. As soldiers tried to wipe away the dampness, cannons began to roar and sheets of flame burst forth from hundreds of rifles, opening a twelve hour tempest that swept across the rolling farm fields in western Maryland. A clash between North and South that changed the course of the Civil War, helped free over four million Americans, devastated Sharpsburg, and still ranks as the bloodiest one-day battle in American history. “…we are driven to protect our “The present seems to be the own country by transferring the most propitious time since the seat of war to that of an enemy commencement of the war for who pursues us with a relentless the Confederate army to enter and apparently aimless hostility.” Maryland.” Jefferson Davis General R.E. Lee September 7, 1862 3 September1862 The Battle of Antietam was the culmination of the Maryland Campaign of 1862, the first invasion of the North by Confederate General Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia. In Kentucky and Missouri, Southern armies were also advancing as the tide of war flowed north. After Lee’s dramatic victory at the Second Battle of Manassas during the last two days of August, he wrote to Confederate President Jefferson Davis that “we cannot afford to be idle.” Lee wanted to keep the offensive and secure Southern independence through victory in the North; influence the fall mid-term elections; obtain much needed supplies; move the war out of Virginia, possibly into Pennsylvania; and to liberate Maryland, a Union state, but a slave-holding border state divided in its sympathies. -

James Longstreet and His Staff of the First Corps

Papers of the 2017 Gettysburg National Military Park Seminar The Best Staff Officers in the Army- James Longstreet and His Staff of the First Corps Karlton Smith Lt. Gen. James Longstreet had the best staff in the Army of Northern Virginia and, arguably, the best staff on either side during the Civil War. This circumstance would help to make Longstreet the best corps commander on either side. A bold statement indeed, but simple to justify. James Longstreet had a discriminating eye for talent, was quick to recognize the abilities of a soldier and fellow officer in whom he could trust to complete their assigned duties, no matter the risk. It was his skill, and that of the officers he gathered around him, which made his command of the First Corps- HIS corps- significantly successful. The Confederate States Congress approved the organization of army corps in October 1862, the law approving that corps commanders were to hold the rank of lieutenant general. President Jefferson Davis General James Longstreet in 1862. requested that Gen. Robert E. Lee provide (Museum of the Confederacy) recommendations for the Confederate army’s lieutenant generals. Lee confined his remarks to his Army of Northern Virginia: “I can confidently recommend Generals Longstreet and Jackson in this army,” Lee responded, with no elaboration on Longstreet’s abilities. He did, however, add a few lines justifying his recommendation of Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson as a corps commander.1 When the promotion list was published, Longstreet ranked as the senior lieutenant general in the Confederate army with a date of rank of October 9, 1862. -

Gettysburg Campaign

MARYLAND CIVIL WAR TRAILS How to Use this Map-Guide This guide depicts four scenic and historic driving tours that follow the routes taken by Union and Confederate armies during the June-July 1863 Gettysburg Campaign. Information contained here and along the Trail tells stories that have been hidden within the landscape for more than 140 years. Follow the bugle trailblazer signs to waysides that chronicle the day-to-day stories of soldiers who marched toward the Civil War’s most epic battles and civilians who, for a second time in nine months, watched their countryside trampled by the boots of the “Blue and Gray.” The Trail can be driven in one, two or three days depending on traveler preference. Destinations like Rockville, Westminster, Frederick, Hagerstown and Cumberland offer walking tours that can be enjoyed all-year long. Recreational activities such as hiking, biking, paddling and horseback riding add a different, yet powerful dimension to the driving experience. Amenities along the Trail include dining, lodging, shopping, and attractions, which highlight Maryland’s important role in the Civil War. For more detailed travel information, stop by any Maryland Welcome Center, local Visitor Center or contact any of the organizations listed in this guide. For additional Civil War Trails information, visit www.civilwartrails.org. For more travel information, visit www.mdwelcome.org. Tim Tadder, www.tadderphotography.com Tadder, Tim Biking through C&O Canal National Historical Park. Follow these signs to more than 1,000 Civil War sites. Detail of painting “Serious Work Ahead” by Civil War Artist Dale Gallon, www.gallon.com, (717) 334-0430. -

“Stonewall” Jackson: a Biography

The Stonewall Jackson House, Lexington, Virginia Discovering Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson: A Biography Thomas Jonathan Jackson was born on January 21, 1824, in Clarksburg, Virginia (now West Virginia). Thomas’ father died when Thomas was two years old, leaving Thomas’ mother widowed with little money and many debts. To support her three surviving children, Thomas’ mother became a teacher and also sewed. Mounting financial problems forced her to sell all her property, even the family home in Clarksburg. Four years later, Thomas’ mother re-married and moved the family to a neighboring county. When Thomas was seven she became very ill and sent the children to live with relatives. Later that year Thomas returned home to be at his mother’s side when she died. Thomas loved his mother deeply, and he remembered her with appreciation all his life. After their mother’s death, Thomas and his sister Laura lived with their Uncle Cummins on Jackson’s Mill. The young Thomas quickly grew to like to his uncle and enjoyed working on the farm. But Thomas lived a lonely and independent life with his uncle, and received only three years of formal schooling. Worse, Thomas did not begin school until he was thirteen. When he was eighteen, Thomas entered the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. Lacking the financial and educational advantages of his classmates, Jackson ranked at the bottom of his class his first year, though he improved with each year. When he was graduated in 1846, Thomas ranked seventeenth out of the fifty-nine graduates in his class. -

Summer 2004 Don Redman Heritage Awards & Concert Park Schedule of Musicians, Actors and Authors Events for 2004 Featured June 26

Published for the Members and Friends IN THIS ISSUE: of the Harpers Ferry Association Annual Historical Association Meeting on June 26 Summer 2004 Don Redman Heritage Awards & Concert Park Schedule of Musicians, Actors and Authors Events for 2004 Featured June 26 n Saturday, June 26, Harpers Ferry National Historical Park will offer ovisitors a day full of cultural events to cel- ebrate Harpers Ferry’s rich history. Plan to join us for historic dramatic presentations, informal meetings with authors, and an evening of jazz music. Actors Bill Barker and Bill Sommerfield will return to the park to portray George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, signifi- cant figures in Harpers Ferry’s history. They will offer presentations at 12:00 noon, 1:00 p.m. and 3:30 p.m. in the Lower Town. Author Fest The Harpers Ferry Historical Association will host visiting authors signing books on the green across from the Bookshop. Visi- tors will have an opportunity to meet these authors and discuss their works between 1:00 p.m. and 4:00 p.m. Featured at this year’s author fest will Confederate Veterans, Jefferson County Gettysburg: This Hallowed be two ladies who have compiled historic Camp No. 123 for the purpose of serving as Ground features Chris photos which have been published in the a guide to the markers in the county that Heisey’s evocative and stir- Images of America Series by Arcadia Publica- identified locations of skirmishes or battles. ring images of the battlefield tions. Dolly Nasby has produced a book This new edition has a biographical sketch landscape.