Historic Structure Report: the Stone House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WA-II-035 Ferry Hill Plantation (Ferry Hill Inn, Ferry Hill Place, Blackford's Plantation)

WA-II-035 Ferry Hill Plantation (Ferry Hill Inn, Ferry Hill Place, Blackford's Plantation) Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 03-12-2004 2-2.--0 z,e34-32-7 Copy 2 WA-II-035 MARYLAND HISTORICAL TRUST WORKSHEET NOMINATION FORM for the NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES, NATIONAL PARKS SERVICE Ferry Hill Inn AND/QR HISTORIC: f2.. LOCATtO_•N~.· _..__ _.._..._..._ _______ ~--~~--~-~----------'-~---"'"-'I STREET ANC' NUMBER: Maryland Route 34 at the Potomac River CITY OR TOWN: Sharpsburg CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS ACCESSIBLE (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC z Yes: 0 District ~ Building 0 Public Public Acquisition: ~ Occupied 0 .8) Restricted D Site 0 Structure 1¥1 Private 0 In Process D Unoccupied Unrestricted 0 Object O Both 0 Being Considered 0 Preservation work D in progress D No PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) 0 Agricultural 0 Government 0 Park 0 Transportation 0 Comments 0 Commercial 0 Industrial 0 Private Residence ~ Other (Specify) 0 Educational 0 Military 0 Religious inn/restaurant 0 Entertainment 0 Museum 0 Scientific z ti(. -

Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and the Fate of the Confederacy

Civil War Book Review Winter 2020 Article 15 The Great Partnership: Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and the Fate of the Confederacy Chris Mackowski Bonaventure University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Mackowski, Chris (2020) "The Great Partnership: Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and the Fate of the Confederacy," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 22 : Iss. 1 . DOI: 10.31390/cwbr.22.1.15 Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol22/iss1/15 Mackowski: The Great Partnership: Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and the Review Chris Mackowski Winter 2020 Keller, Christian B., The Great Partnership: Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and the Fate of the Confederacy. Pegasus Books, 2019. HARDCOVER. $18.89. ISBN: 978-1643131344 pp. 328. The cover of Christian Keller’s latest book, The Great Partnership, features a Mort Künstler painting titled Tactics and Strategy. A fatherly Robert E. Lee, seated on a crackerbox, rests a bare hand on the gloved forearm of Stonewall Jackson, crouching beside him and looking attentively at his commander. The 2002 painting captures a key moment in their partnership: the campfire-lit evening of May 1, 1863, at Chancellorsville. The painting’s title suggests their relationship: Jackson the tactician and Lee the strategist. Ironically, Keller’s book argues a different relationship between the two men. “Lee’s mind, like [Jackson’s], was not limited to the tactical or even the operational objectives in his immediate line of sight,” Keller writes. “The army commander thought more broadly, strategically, in ways that signified a clear understanding of what had to be done to win the war....” (10) In this, Keller argues, Lee and Jackson were in near-perfect synchronicity. -

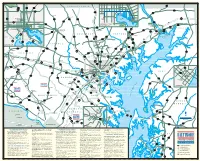

Brochure Design by Communication Design, Inc., Richmond, VA 8267 Main Street Destinations Like Chestertown, Port Deposit, Bel Air, Ellicott City, WASHINGTON, D.C

BALTIMOREST. P . R ESI . Druid Hill Park . 1 . D UL ST . E ST NT PENNSYLV ANIA PA WATER ST. ARD ST S VERT ST AW T 25 45 147 . EUT SAINT HOW HOPKINS PL LOMBARD ST. CHARLES ST CAL SOUTH ST MARKET PL M ASON AND DIXON LINE S . 83 U Y ST 273 PRATTST. COMMERCE ST GA S NORTH AVE. 1 Q Emmitsburg Greenmount 45 ST. U Cemetery FAWN E 1 H . T S A T H EASTERN AVE. N G USS Constellation I Union Mills L N SHARP ST CONWAYST. A Manchester R Taneytown FLEET ST. AY I Washington Monument/ Camden INNER V 1 E Mt. Vernon Place 97 30 25 95 Station R MONUMENT ST. BROADW HARBOR President Maryland . Street 27 Station LANCASTER ST. Historical Society . ORLEANS ST. ERT ST T . S Y 222 40 LV A Thurmont G Church Home CA Susquehanna Mt. Clare and Hospital KEY HWY Battle Monument 140 BALTIMORE RIOT TRAIL State Park Port Deposit ELKTON Mansion BALTIMORE ST. CHARLES ST (1.6-mile walking tour) 7 LOMBARD ST. Federal Hill James Archer L 77 Birthplace A PRATT ST. Middleburg Patterson P I Old Frederick Road D 40 R Park 138 U M (Loy’s Station) . EASTERN AVE. E R CONWAY ST. D V Mt. Clare Station/ B 137 Hereford CECIL RD ST USS O T. S I VE. FLEET ST. T 84 24 1 A B&O Railroad Museum WA O K TS RIC Constellation Union Bridge N R DE Catoctin S Abbott F 7 E HO FR T. WESTMINSTER A 155 L Monkton Station Furnance LIGH Iron Works L T (Multiple Trail Sites) S 155 RD 327 462 S 31 BUS A Y M 1 Federal O R A E K I Havre de Grace Rodgers R Hill N R S D T 22 Tavern Perryville E 395 BALTIMORE HARFORD H V K E Community Park T I Y 75 Lewistown H New Windsor W Bel Air Court House R R Y 140 30 25 45 146 SUSQUEHANNA O K N BUS FLATS L F 1 OR ABERDEEN E T A VE. -

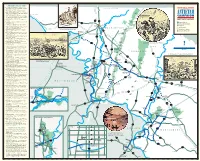

Antietam Map Side

★ ANTIETAM CAMPAIGN SITES★ ★ Leesburg (Loudoun Museum) – Antietam Campaign To ur begins here, where Lee rested the Army of Northern MASON/DIXON LINE Virginia before invading Maryland. ★ Mile Hill – A surprise attack led by Confederate Col. Thomas Munford on Sept. 2, 1862, routed Federal forces. ★ White’s Ferry (C&O Canal NHP) – A major part of Lee’s army forded the Potomac River two miles north of this mod- ern ferry crossing, at White’s Ford. To Cumberland, Md. ★ White’s Ford (C&O Canal NHP) – Here the major part of the Army of Northern Virginia forded the Potomac River into Maryland on September 5-6, 1862, while a Confederate band played “Maryland! My Maryland!” ★ Poolesville – Site of cavalry skirmishes on September 5 & 8, 1862. 81 11 ★ Beallsville – A running cavalry fight passed through town Campaign Driving Route on September 9, 1862. 40 ★ Barnesville – On September 9, 1862, opposing cavalry Alternate Campaign Driving Route units chased each other through town several times. Rose Hill HAGERSTOWN Campaign Site ★ Comus (Mt. Ephraim Crossroads) – Confederate cavalry Cemetery fought a successful rearguard action here, September 9-11, Other Civil War Site 1862, to protect the infantry at Frederick. The German Reformed Church in Keedysville W ASHINGTON ★ Sugarloaf Mountain – At different times, Union and was used as a hospital after the battle. National, State or County Park Confederate signalmen atop the mountain watched the 40 I L InformationInformation or Welcome Center opposing army. Williamsport R A T ★ Monocacy Aqueduct (C&O Canal NHP) – Confederate (C&O Canal NHP) troops tried and failed to destroy or damage the aqueduct South Mountain N on September 4 & 9, 1862. -

Summer 2004 Don Redman Heritage Awards & Concert Park Schedule of Musicians, Actors and Authors Events for 2004 Featured June 26

Published for the Members and Friends IN THIS ISSUE: of the Harpers Ferry Association Annual Historical Association Meeting on June 26 Summer 2004 Don Redman Heritage Awards & Concert Park Schedule of Musicians, Actors and Authors Events for 2004 Featured June 26 n Saturday, June 26, Harpers Ferry National Historical Park will offer ovisitors a day full of cultural events to cel- ebrate Harpers Ferry’s rich history. Plan to join us for historic dramatic presentations, informal meetings with authors, and an evening of jazz music. Actors Bill Barker and Bill Sommerfield will return to the park to portray George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, signifi- cant figures in Harpers Ferry’s history. They will offer presentations at 12:00 noon, 1:00 p.m. and 3:30 p.m. in the Lower Town. Author Fest The Harpers Ferry Historical Association will host visiting authors signing books on the green across from the Bookshop. Visi- tors will have an opportunity to meet these authors and discuss their works between 1:00 p.m. and 4:00 p.m. Featured at this year’s author fest will Confederate Veterans, Jefferson County Gettysburg: This Hallowed be two ladies who have compiled historic Camp No. 123 for the purpose of serving as Ground features Chris photos which have been published in the a guide to the markers in the county that Heisey’s evocative and stir- Images of America Series by Arcadia Publica- identified locations of skirmishes or battles. ring images of the battlefield tions. Dolly Nasby has produced a book This new edition has a biographical sketch landscape. -

Heart of the Civil War Heritage Area Guide Page 1 on The

Scots-Irish families moved into these PENNSYLVANIA Heart of the OH counties from the south. These settlers Mason-Dixon Line from southeastern portions of Maryland NJ Civil War MARYLAND assimilated smoothly with their DC Dutch brethren. Heritage WEST VIRGINIA DE Slavery was found throughout this Area Guide VIRGINIA region but took on new meaning after Pennsylvania abolished the institution in The HCWHA is ideally positioned to serve 1781. The western part of the Mason-Dixon as your “base camp” for driving the popular Line and the Ohio River became a border Maryland Civil War Trails and visiting the between free and slave states, although battlefields and sites of Antietam, Gettysburg, The Mason-Dixon Line Delaware remained a slave state. By the Monocacy, South Mountain, Harpers Ferry, The Heart of the Civil War Heritage Area is 1850s, the Mason-Dixon Line symbolically Baltimore, and Washington, D.C. adjacent to the Mason-Dixon Line, generally viewed as the dividing line between North became the cultural boundary between and South. This geographic location offers the Northern and Southern United States. opportunities to discuss both sides of the The Potomac River marked the southern monumental conflict and to examine the At the Heart of it All… boundary of Washington County While the word “heart” denotes the center unique experience of “border states” and and southwestern Frederick County. or core of some thing or place, it also relates individual communities that were divided This famed waterway became the true to three major Civil War themes found in loyalty. within this geographic area, exemplified dividing line between North and South by the images on this brochure’s cover. -

C&O Canal Trail to History

C &O Canal {TRAIL to HISTORY} SHEPHERDSTOWN SHARPSBURG WILLIAMSPORT www.canaltrust.org C &O Canal {TRAIL to HISTORY} Take a journey into the rich history of our Canal Towns along the C&O Canal towpath. Explore our region in your car, ride a bike, raft the river or take a leisurely stroll in our Between Shepherdstown and Williamsport, historic towns. Visit our historical parks and learn about the Potomac River and the C&O Canal follow our region’s rich history. Pioneer settlement, transportation innovations, struggles for freedom—it all happened here. a 25-mile serpentine path through an area Visit, explore and enjoy! of pastoral landscapes and rich, historical heritage. The distance is significantly shorter by road. Bustling canal construction and trade helped form all three of these towns, but remembrances of September 1862 loom even larger today. Still, along with battlefields, aqueducts and historic houses, tourists in this region can also take in contemporary drama, fine dining, and some of the best local ice cream in the Mid-Atlantic. 2 3 Shepherdstown Covered Bridge SHEPHERDSTOWN } SHEPHERDSTOWN As you near Shepherdstown from the east along the C&O Canal, you will pass Boteler’s Ford, or Pack Horse Ford, an easy crossing of the Potomac during low or moderate water levels. Stonewall Jackson’s troops made the crossing Mellow Moods Café in September 1862 on their way from Harpers Ferry to the Battle of Antietam. After that watershed event, when Robert Today, Shepherdstown is a lively college town and cultural E. Lee’s Army retreated back into what was then Virginia, the center, and you can enjoy its restaurants and lodging or visit shelling and shooting across the river here were described by its bike shop without giving a thought to Civil War matters. -

Page 1 H a R F O R D C E C I L K E N T Q U E E N a N N E's Tu C K

BALTIMORE ST. P R E S I 1 Druid Hill Park D E PENNSYLVANIA WATER ST. N T S T 25 45 147 . EUTAW ST. EUTAW ST. HOWARD HOPKINS PL. LOMBARD ST. CHARLES ST. ST. SAINT PAUL ST. CALVERT SOUTH ST. MARKET PL. MASON AND DIXON LINE S 83 U 273 PRATT ST. COMMERCE ST. ST. GAY S NORTH AVE. 1 Q Emmitsburg Greenmount 45 T. N S U Cemetery FAW E 1 H . T S A T H EASTERN AVE. N G USS Constellation I Union Mills L N SHARP ST. CONWAY ST. A Taneytown Manchester R FLEET ST. I Washington Monument/ Camden INNER V 1 Mt. Vernon Place 97 30 25 E 95 Station R MONUMENT ST. BROADWAY HARBOR President Maryland Street 27 Station LANCASTER ST. Historical Society . ORLEANS ST. ST 222 Y 40 A Thurmont G Church Home CALVERT ST. CALVERT KEY HWY Susquehanna Mt. Clare Battle Monument and Hospital BALTIMORE RIOT TRAIL State Park Port Deposit ELKTON Mansion 140 BALTIMORE ST. CHARLES ST. 7 (1.6-mile walking tour) Federal Hill James Archer LOMBARD ST. L 77 Birthplace A Middleburg Patterson P PRATT ST. I Old Frederick Road D 40 R Park 138 U (Loy’s Station) M E EASTERN AVE. R CONWAY ST. D 137 Hereford V CECIL Mt. Clare Station/ B USS O 24 1 I E. FLEET ST. S 84 AV B&O Railroad Museum Union Bridge TO ICK Constellation N 7 R ER Catoctin F D S Abbott WESTMINSTER A RE ST. HOWARD T 155 F . L Monkton Station L T Furnance LIGHT ST. -

The Development of a Legend: Stonewall Jackson As a Southern Hero

Stonewall Jackson 1 Running head: STONEWALL JACKSON The Development of a Legend: Stonewall Jackson as a Southern Hero Andrew Chesnut A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2008 Stonewall Jackson 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Brian Melton, Ph.D. Chairman of Thesis ______________________________ Cline Hall, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Charles Murphy, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ James Nutter, D.A. Honors Director ______________________________ Date Stonewall Jackson 3 Abstract Throughout history, most individuals have lived their lives, and then faded into oblivion with little to remember them by. Relatively few receive credit for significantly affecting the course of human history and obtain appropriate remembrance in accounts of the past. For those whose memories endure, due to the unrepeatable nature of past events, history remains vulnerable to the corrupting influence of myths and legends that distort historical realities. Confederate Lieutenant General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson (1824-1863) serves as a prime example of an historical figure, who, though deserving of his place in history, has been subsequently distorted by biographers and memory. The following discussion largely passes over the general’s already well-analyzed military career, and explores other factors that contributed to his incredible rise in fame to the exalted position of southern hero. Topics include Jackson’s well-documented eccentricities, the manner of his death, the social climate of the post-war South, and his subsequent treatment by early biographers. -

A Novel of Lee's Army in Maryland, 1862

Civil War Book Review Winter 2018 Article 19 Six Days In September: A Novel Of Lee's Army In Maryland, 1862 Meg Groeling Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Groeling, Meg (2018) "Six Days In September: A Novel Of Lee's Army In Maryland, 1862," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 20 : Iss. 1 . DOI: 10.31390/cwbr.20.1.24 Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol20/iss1/19 Groeling: Six Days In September: A Novel Of Lee's Army In Maryland, 1862 Review Groeling, Meg Winter 2018 Rossino, Alexander Six Days in September: A novel of Lee\'s Army in Maryland, 1862. Savas Beatie, $18.95 ISBN 9781611213454 A Different View from South Mountain Author Alexander B. Rossino, Ph.D. is not only an award-winning historian usually working in the area of WWII, but also a lifelong Civil War buff. He currently lives in western Maryland at the foot of South Mountain, and that geographic area has worked its magic once again, giving us Six Days in September, a novel of Lee's army in Maryland. Beginning on September 13, 1862, and continuing through the Battle of Antietam, Rossino reconstructs the Army of Northern Virginia from the top down. His "characters" are drawn from the letters, orders, and experiences of the men who were serving under General Robert E. Lee and include Lee himself. Lee's interactions with Longstreet are of particular interest. Most readers are familiar with the issues between both men that surfaced at Gettysburg. Rossino plants the seeds for the distance in their relationship as early as ‘62. -

S Antietam * Monuments

They stand like silent sentinels, vigilantly watching over the pastoral landscape. The monuments at Antietam National Battlefield are tangible reminders of a s Antietam Program from Lee costly war and America's bloodiest day. Whether they are grand sculptured Memorial dedication, columns or simple stones, granite or bronze, each monument has a story. A Veterans of the Blue and * Monuments permanent record of dedication, courage, and sacrifice that is reflected in each Gray, Ribbon from 130th monument's unique design and artistry. Pennsylvania Monument dedication. Souvenir book from 14th Connecticut The monuments were placed by veterans of the battle, and the states that Infantry reunion. participated. They are typically located where the soldiers, regiments, or brigades fought during the battle. There are currently ninety-six monuments at Antietam, the majority of which represent the Union army. After the war, the former Confederacy was so devastated it was difficult for the veterans to raise the needed money to build monuments. Nearby Pennsylvania has the most monuments in the park. There are six state monuments and eight dedicated to individuals. The time period that the majority of the monuments were erected was from 1890 to 1910. During these two decades there was a confluence of events that led to a rapid growth of monumentation, here at Antietam and at many other battlefields. First, the U.S. War Department created five national military parks, including Antietam, for the purpose of military study in the 1890s. This formalized the idea that the land was to be preserved and commemorated. Secondly, veterans of the Civil War had developed both the economic and political strength required to get monuments built. -

Maintaining Order in the Midst of Chaos: Robert E. Lee's

MAINTAINING ORDER IN THE MIDST OF CHAOS: ROBERT E. LEE’S USAGE OF HIS PERSONAL STAFF A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Robert William Sidwell May, 2009 Thesis written by Robert William Sidwell B.A., Ohio University, 2005 M.A., Ohio University, 2007 M.A., Kent State University, 2009 Approved by _____Kevin Adams____________________, Advisor _____Kenneth J. Bindas________________ , Chair, Department of History _____John R. D. Stalvey________________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………iv Chapter I. Introduction…………………………………………………………………….1 II. The Seven Days: The (Mis)use of an Army Staff…………………………….17 III. The Maryland Campaign: Improvement in Staff Usage……………………..49 IV. Gettysburg: The Limits of Staff Improvement………………………………82 V. Conclusion......................................................................................................121 BIBLIOGRAPHY...........................................................................................................134 iii Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank the history faculty at Kent State University for their patience and wise counsel during the preparation of this thesis. In particular, during a graduate seminar, Dr. Kim Gruenwald inspired this project by asking what topics still had never been written about concerning the American Civil War. Dr. Leonne Hudson assisted greatly with advice on editing and style, helping the author become a better writer in the process. Finally, Dr. Kevin Adams, who advised this project, was very patient, insightful, and helpful. The author also deeply acknowledges the loving support of his mother, Beverly Sidwell, who has encouraged him at every stage of the process, especially during the difficult or frustrating times, of which there were many. She was always there to lend a word of much-needed support, and she can never know how much her aid is appreciated.