Chinese Names of New Elements with Z = 113, 115, 117 &

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development of the Periodic Table and Its Consequences Citation: J

Firenze University Press www.fupress.com/substantia The Development of the Periodic Table and its Consequences Citation: J. Emsley (2019) The Devel- opment of the Periodic Table and its Consequences. Substantia 3(2) Suppl. 5: 15-27. doi: 10.13128/Substantia-297 John Emsley Copyright: © 2019 J. Emsley. This is Alameda Lodge, 23a Alameda Road, Ampthill, MK45 2LA, UK an open access, peer-reviewed article E-mail: [email protected] published by Firenze University Press (http://www.fupress.com/substantia) and distributed under the terms of the Abstract. Chemistry is fortunate among the sciences in having an icon that is instant- Creative Commons Attribution License, ly recognisable around the world: the periodic table. The United Nations has deemed which permits unrestricted use, distri- 2019 to be the International Year of the Periodic Table, in commemoration of the 150th bution, and reproduction in any medi- anniversary of the first paper in which it appeared. That had been written by a Russian um, provided the original author and chemist, Dmitri Mendeleev, and was published in May 1869. Since then, there have source are credited. been many versions of the table, but one format has come to be the most widely used Data Availability Statement: All rel- and is to be seen everywhere. The route to this preferred form of the table makes an evant data are within the paper and its interesting story. Supporting Information files. Keywords. Periodic table, Mendeleev, Newlands, Deming, Seaborg. Competing Interests: The Author(s) declare(s) no conflict of interest. INTRODUCTION There are hundreds of periodic tables but the one that is widely repro- duced has the approval of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and is shown in Fig.1. -

FRANCIUM Element Symbol: Fr Atomic Number: 87

FRANCIUM Element Symbol: Fr Atomic Number: 87 An initiative of IYC 2011 brought to you by the RACI KAYE GREEN www.raci.org.au FRANCIUM Element symbol: Fr Atomic number: 87 Francium (previously known as eka-cesium and actinium K) is a radioactive metal and the second rarest naturally occurring element after Astatine. It is the least stable of the first 103 elements. Very little is known of the physical and chemical properties of Francium compared to other elements. Francium was discovered by Marguerite Perey of the Curie Institute in Paris, France in 1939. However, the existence of an element of atomic number 87 was predicted in the 1870s by Dmitri Mendeleev, creator of the first version of the periodic table, who presumed it would have chemical and physical properties similar to Cesium. Several research teams attempted to isolate this missing element, and there were at least four false claims of discovery during which it was named Russium (after the home country of soviet chemist D. K. Dobroserdov), Alkalinium (by English chemists Gerald J. K. Druce and Frederick H. Loring as the heaviest alkali metal), Virginium (after Virginia, home state of chemist Fred Allison), and Moldavium (by Horia Hulubei and Yvette Cauchois after Moldavia, the Romanian province where they conducted their work). Perey finally discovered Francium after purifying radioactive Actinium-227 from Lanthanum, and detecting particles decaying at low energy levels not previously identified. The new product exhibited chemical properties of an alkali metal (such as co-precipitating with Cesium salts), which led Perey to believe that it was element 87, caused by the alpha radioactive decay of Actinium-227. -

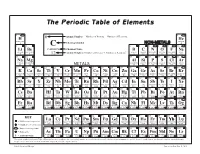

The Periodic Table of Elements

The Periodic Table of Elements 1 2 6 Atomic Number = Number of Protons = Number of Electrons HYDROGENH HELIUMHe 1 Chemical Symbol NON-METALS 4 3 4 C 5 6 7 8 9 10 Li Be CARBON Chemical Name B C N O F Ne LITHIUM BERYLLIUM = Number of Protons + Number of Neutrons* BORON CARBON NITROGEN OXYGEN FLUORINE NEON 7 9 12 Atomic Weight 11 12 14 16 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 SODIUMNa MAGNESIUMMg ALUMINUMAl SILICONSi PHOSPHORUSP SULFURS CHLORINECl ARGONAr 23 24 METALS 27 28 31 32 35 40 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 POTASSIUMK CALCIUMCa SCANDIUMSc TITANIUMTi VANADIUMV CHROMIUMCr MANGANESEMn FeIRON COBALTCo NICKELNi CuCOPPER ZnZINC GALLIUMGa GERMANIUMGe ARSENICAs SELENIUMSe BROMINEBr KRYPTONKr 39 40 45 48 51 52 55 56 59 59 64 65 70 73 75 79 80 84 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 RUBIDIUMRb STRONTIUMSr YTTRIUMY ZIRCONIUMZr NIOBIUMNb MOLYBDENUMMo TECHNETIUMTc RUTHENIUMRu RHODIUMRh PALLADIUMPd AgSILVER CADMIUMCd INDIUMIn SnTIN ANTIMONYSb TELLURIUMTe IODINEI XeXENON 85 88 89 91 93 96 98 101 103 106 108 112 115 119 122 128 127 131 55 56 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 CESIUMCs BARIUMBa HAFNIUMHf TANTALUMTa TUNGSTENW RHENIUMRe OSMIUMOs IRIDIUMIr PLATINUMPt AuGOLD MERCURYHg THALLIUMTl PbLEAD BISMUTHBi POLONIUMPo ASTATINEAt RnRADON 133 137 178 181 184 186 190 192 195 197 201 204 207 209 209 210 222 87 88 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 FRANCIUMFr RADIUMRa RUTHERFORDIUMRf DUBNIUMDb SEABORGIUMSg BOHRIUMBh HASSIUMHs MEITNERIUMMt DARMSTADTIUMDs ROENTGENIUMRg COPERNICIUMCn NIHONIUMNh -

Microdosimetry of Astatine-211 and Xa0102708 Comparison with That of Iodine-125

MICRODOSIMETRY OF ASTATINE-211 AND XA0102708 COMPARISON WITH THAT OF IODINE-125 T. UNAK Ege University, Bomova, Izmir, Turkey Abstract.' 21lAt is an alpha and Auger emitter radionuclide and has been frequently used for labeling of different kind of chemical agents. 125I is also known as an effective Auger emitter. The radionuclides which emit short range and high LET radiations such as alpha particles and Auger electrons have high radiotoxic effectiveness on the living systems. The microdosimetric data are suitable to clarify the real radiotoxic effectiveness and to get the detail of diagnostic and therapeutic application principles of these radionuclides. In this study, the energy and dose absorptions by cell nucleus from alpha particles and Auger electrons emitted by 211At have been calculated using a Monte Carlo calculation program (code: UNMOC). For these calculations two different model corresponding to the cell nucleus have been used and the data obtained were compared with the data earlier obtained for I25I. As a result, the radiotoxicity of 21lAt is in the competition with 125I. In the case of a specific agent labelled with 2I1At or 125I is incorporated into the cell or cell nucleus, but non-bound to DNA or not found very close to it, 2llAt should considerably be much more radiotoxic than i25I, but in the case of the labelled agent is bound to DNA or take a place very close to it, the radiotoxicity of i25I should considerably be higher than 21'At. 1. INTRODUCTION 21'At as an alpha and Auger emitter radionuclide has an extremely high potential application in cancer therapy; particularly, in molecular radiotherapy. -

Classification of Elements and Periodicity in Properties

74 CHEMISTRY UNIT 3 CLASSIFICATION OF ELEMENTS AND PERIODICITY IN PROPERTIES The Periodic Table is arguably the most important concept in chemistry, both in principle and in practice. It is the everyday support for students, it suggests new avenues of research to After studying this Unit, you will be professionals, and it provides a succinct organization of the able to whole of chemistry. It is a remarkable demonstration of the fact that the chemical elements are not a random cluster of • appreciate how the concept of entities but instead display trends and lie together in families. grouping elements in accordance to An awareness of the Periodic Table is essential to anyone who their properties led to the wishes to disentangle the world and see how it is built up development of Periodic Table. from the fundamental building blocks of the chemistry, the understand the Periodic Law; • chemical elements. • understand the significance of atomic number and electronic Glenn T. Seaborg configuration as the basis for periodic classification; • name the elements with In this Unit, we will study the historical development of the Z >100 according to IUPAC Periodic Table as it stands today and the Modern Periodic nomenclature; Law. We will also learn how the periodic classification • classify elements into s, p, d, f follows as a logical consequence of the electronic blocks and learn their main configuration of atoms. Finally, we shall examine some of characteristics; the periodic trends in the physical and chemical properties • recognise the periodic trends in of the elements. physical and chemical properties of elements; 3.1 WHY DO WE NEED TO CLASSIFY ELEMENTS ? compare the reactivity of elements • We know by now that the elements are the basic units of all and correlate it with their occurrence in nature; types of matter. -

The Oganesson Odyssey Kit Chapman Explores the Voyage to the Discovery of Element 118, the Pioneer Chemist It Is Named After, and False Claims Made Along the Way

in your element The oganesson odyssey Kit Chapman explores the voyage to the discovery of element 118, the pioneer chemist it is named after, and false claims made along the way. aving an element named after you Ninov had been dismissed from Berkeley for is incredibly rare. In fact, to be scientific misconduct in May5, and had filed Hhonoured in this manner during a grievance procedure6. your lifetime has only happened to Today, the discovery of the last element two scientists — Glenn Seaborg and of the periodic table as we know it is Yuri Oganessian. Yet, on meeting Oganessian undisputed, but its structure and properties it seems fitting. A colleague of his once remain a mystery. No chemistry has been told me that when he first arrived in the performed on this radioactive giant: 294Og halls of Oganessian’s programme at the has a half-life of less than a millisecond Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR) before it succumbs to α -decay. in Dubna, Russia, it was unlike anything Theoretical models however suggest it he’d ever experienced. Forget the 2,000 ton may not conform to the periodic trends. As magnets, the beam lines and the brand new a noble gas, you would expect oganesson cyclotron being installed designed to hunt to have closed valence shells, ending with for elements 119 and 120, the difference a filled 7s27p6 configuration. But in 2017, a was Oganessian: “When you come to work US–New Zealand collaboration predicted for Yuri, it’s not like a lab,” he explained. that isn’t the case7. -

Of the Periodic Table

of the Periodic Table teacher notes Give your students a visual introduction to the families of the periodic table! This product includes eight mini- posters, one for each of the element families on the main group of the periodic table: Alkali Metals, Alkaline Earth Metals, Boron/Aluminum Group (Icosagens), Carbon Group (Crystallogens), Nitrogen Group (Pnictogens), Oxygen Group (Chalcogens), Halogens, and Noble Gases. The mini-posters give overview information about the family as well as a visual of where on the periodic table the family is located and a diagram of an atom of that family highlighting the number of valence electrons. Also included is the student packet, which is broken into the eight families and asks for specific information that students will find on the mini-posters. The students are also directed to color each family with a specific color on the blank graphic organizer at the end of their packet and they go to the fantastic interactive table at www.periodictable.com to learn even more about the elements in each family. Furthermore, there is a section for students to conduct their own research on the element of hydrogen, which does not belong to a family. When I use this activity, I print two of each mini-poster in color (pages 8 through 15 of this file), laminate them, and lay them on a big table. I have students work in partners to read about each family, one at a time, and complete that section of the student packet (pages 16 through 21 of this file). When they finish, they bring the mini-poster back to the table for another group to use. -

About That Atomic Weight

BOOKS & ARTS All about that atomic weight creating and proving the existence of these ele- Shaughnessy was involved in the discovery of ments, the stories in the book almost certainly all the recently discovered elements, and was would have been rejected as implausible fiction also the undisputed champion of the unoffi- were they included in a script for a blockbuster cial LLNL contest to see who could watch Star movie on the Transfermium Wars. Wars: The Force Awakens the most times in Chapman’s book is part science, part his- theatres. These stories will undoubtedly make tory, part multi-subject biography told chrono- Superheavy more accessible to audiences with logically with his travelogue interspersed limited knowledge of nuclear chemistry, such throughout. When he reaches Berkeley, he as high school and college chemistry students. realizes, as I once did, that one should pack a Although Chapman demonstrates a deep sweatshirt or two when visiting the Bay Area knowledge of science fiction, one might expect during the summer. Chapman also makes stops the next meeting of the Avengers to be a little in Sweden, Japan, Italy and several other coun- awkward when Thor cites Chapman’s asser- tries to trace the steps of the element hunters tion that thorium is the only comic book char- who pushed the limits of nuclear chemistry to acter to appear on the periodic table. Captain fill in the periodic table. In particular, Chapman America and Iron Man might disagree with Superheavy: Making and Breaking the spends time at the Joint Institute for Nuclear that claim. Chapman should be prepared as Periodic Table Research in Dubna, Russia, interviewing Yuri Titanium Man, Cobalt Man and all the Metal Edited by Kit Chapman Oganessian, who lends his name to element Men also might pay him a visit in the not too Bloomsbury Sigma, 2019, 304pp, £16.99. -

Enigmatic Astatine D

in your element Enigmatic astatine D. Scott Wilbur points out the difficulty in studying the transient element astatine, and the need to understand its basic chemical nature to help in the development of targeted radiotherapy agents. ince the discovery of astatine The other ‘long’-lived isotope, 210At, is not of labelling reagents containing more over 70 years ago1, many of its suitable because it decays into polonium-210 stable aromatic astatine–boron bonds Scharacteristics have remained elusive. — the notorious radiation poison used to has improved that situation, and studies Unlike the other halogens, abundant and kill the Russian Federal Security Service evaluating bonding with other elements ubiquitous in nature, astatine is one of officer Alexander Litvinenko in 2006, may further advance it. the rarest of all elements. This arises from after he took political asylum in the To determine in vivo stability, the the fact that it has no stable isotopes; the United Kingdom. same cancer-targeting molecule can longest lived of its 32 known radioisotopes, Although some chemical data has be labelled with 211At and (stably) with 210At, has a half-life of only 8.1 hours. been compiled for astatine isotopes, radioiodine (125I, 123I or 131I), and the two The rarity and radioactive nature of many physical properties have only been co-injected. The concentrations of 211At element 85 lends to its mystery, as it cannot extrapolated. Similar to other halogens, in various tissues (higher lung, spleen, be observed or weighed in a conventional astatine undergoes nucleophilic and stomach and thyroid) indicate whether it is sense. Even its colour is unknown; based electrophilic reactions. -

Unit 6 the Periodic Table How to Group Elements Together? Elements of Similar Properties Would Be Group Together for Convenience

Unit 6 The periodic table How to group elements together? Elements of similar properties would be group together for convenience. The periodic table Chemists group elements with similar chemical properties together. This gives rise to the periodic table. In the periodic table, elements are arranged according to the following criteria: 1. in increasing order of atomic numbers and 2. according to the electronic arrangement The diagram below shows a simplified periodic table with the first 36 elements listed. Groups The vertical columns in the periodic table are called groups . Groups are numbered from I to VII, followed by Group 0 (formerly called Group VIII). [Some groups are without group numbers.] The table below shows the electronic arrangements of some elements in some groups. Group I Group II Group VII Group 0 He (2) Li (2,1) Be (2,2) F (2,7) Ne (2,8) Na (2,8,1) Mg (2,8,2) Cl (2,8,7) Ar (2,8,8) K (2,8,8,1) Ca (2,8,8,2) Br (2,8,18,7) Kr (2,8,18,8) What is the relationship between the group numbers and the electronic arrangements of the elements? Group number = the number of outermost shell electrons in an atom of the element The chemical properties of an element depend mainly on the number of outermost shell electrons in its atoms. Therefore, elements within the same group would have similar chemical properties and would react in a similar way. However, there would be a gradual change of reactivity of the elements as we move down the group. -

No. It's Livermorium!

in your element Uuh? No. It’s livermorium! Alpha decay into flerovium? It must be Lv, saysKat Day, as she tells us how little we know about element 116. t the end of last year, the International behaviour in polonium, which we’d expect to Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry have very similar chemistry. The most stable A(IUPAC) announced the verification class of polonium compounds are polonides, of the discoveries of four new chemical for example Na2Po (ref. 8), so in theory elements, 113, 115, 117 and 118, thus Na2Lv and its analogues should be attainable, completing period 7 of the periodic table1. though they are yet to be synthesized. Though now named2 (no doubt after having Experiments carried out in 2011 showed 3 213 212m read the Sceptical Chymist blog post ), that the hydrides BiH3 and PoH2 were 9 we shall wait until the public consultation surprisingly thermally stable . LvH2 would period is over before In Your Element visits be expected to be less stable than the much these ephemeral entities. lighter polonium hydride, but its chemical In the meantime, what do we know of investigation might be possible in the gas their close neighbour, element 116? Well, after phase, if a sufficiently stable isotope can a false start4, the element was first legitimately be found. reported in 2000 by a collaborative team Despite the considerable challenges posed following experiments at the Joint Institute for by the short-lived nature of livermorium, EMMA SOFIA KARLSSON, STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN STOCKHOLM, KARLSSON, EMMA SOFIA Nuclear Research (JINR) in Dubna, Russia. -

Periodic Table 1 Periodic Table

Periodic table 1 Periodic table This article is about the table used in chemistry. For other uses, see Periodic table (disambiguation). The periodic table is a tabular arrangement of the chemical elements, organized on the basis of their atomic numbers (numbers of protons in the nucleus), electron configurations , and recurring chemical properties. Elements are presented in order of increasing atomic number, which is typically listed with the chemical symbol in each box. The standard form of the table consists of a grid of elements laid out in 18 columns and 7 Standard 18-column form of the periodic table. For the color legend, see section Layout, rows, with a double row of elements under the larger table. below that. The table can also be deconstructed into four rectangular blocks: the s-block to the left, the p-block to the right, the d-block in the middle, and the f-block below that. The rows of the table are called periods; the columns are called groups, with some of these having names such as halogens or noble gases. Since, by definition, a periodic table incorporates recurring trends, any such table can be used to derive relationships between the properties of the elements and predict the properties of new, yet to be discovered or synthesized, elements. As a result, a periodic table—whether in the standard form or some other variant—provides a useful framework for analyzing chemical behavior, and such tables are widely used in chemistry and other sciences. Although precursors exist, Dmitri Mendeleev is generally credited with the publication, in 1869, of the first widely recognized periodic table.