Joseph Cook's Contribution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1835. EXECUTIVE. *L POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT

1835. EXECUTIVE. *l POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT. Persons employed in the General Post Office, with the annual compensation of each. Where Compen Names. Offices. Born. sation. Dol. cts. Amos Kendall..., Postmaster General.... Mass. 6000 00 Charles K. Gardner Ass't P. M. Gen. 1st Div. N. Jersey250 0 00 SelahR. Hobbie.. Ass't P. M. Gen. 2d Div. N. York. 2500 00 P. S. Loughborough Chief Clerk Kentucky 1700 00 Robert Johnson. ., Accountant, 3d Division Penn 1400 00 CLERKS. Thomas B. Dyer... Principal Book Keeper Maryland 1400 00 Joseph W. Hand... Solicitor Conn 1400 00 John Suter Principal Pay Clerk. Maryland 1400 00 John McLeod Register's Office Scotland. 1200 00 William G. Eliot.. .Chie f Examiner Mass 1200 00 Michael T. Simpson Sup't Dead Letter OfficePen n 1200 00 David Saunders Chief Register Virginia.. 1200 00 Arthur Nelson Principal Clerk, N. Div.Marylan d 1200 00 Richard Dement Second Book Keeper.. do.. 1200 00 Josiah F.Caldwell.. Register's Office N. Jersey 1200 00 George L. Douglass Principal Clerk, S. Div.Kentucky -1200 00 Nicholas Tastet Bank Accountant Spain. 1200 00 Thomas Arbuckle.. Register's Office Ireland 1100 00 Samuel Fitzhugh.., do Maryland 1000 00 Wm. C,Lipscomb. do : for) Virginia. 1000 00 Thos. B. Addison. f Record Clerk con-> Maryland 1000 00 < routes and v....) Matthias Ross f. tracts, N. Div, N. Jersey1000 00 David Koones Dead Letter Office Maryland 1000 00 Presley Simpson... Examiner's Office Virginia- 1000 00 Grafton D. Hanson. Solicitor's Office.. Maryland 1000 00 Walter D. Addison. Recorder, Div. of Acc'ts do.. -

Votes and Proceedings

129 129 1913. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. No. 48. VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. FRIDAY, 31ST OCTOBER, 1913. 1. The H[ou, mielt, at half-past ten o'clock a.m., puirsunt to adjourniiniit.Mr. Speaker took the Chair, .and read Prayers. 2. MESSAGES FROM THE GOVERNOR-GENERAL.-ASSENT TO BILLS.-The following Messages from His Excellency the Governor-General were presented, and the same were read by IMr.Speaker :- (Supply Bill (No. 4) 1913-14)-- DENMAN, Governor-General. Message No. 17. A Bill intituled " An Act to grant and apply a sum out of the Consolidated Revenue Fund for the service of the year ending the thirtieth day of June One thousand nine hundred and fourteen," as finally passed by the Senate and the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth, having been presented to the -Governor-General for the Royal Assent, His Excellency has, in the name and on behalf of His Majesty, assented to the said Act. Government House, Melbourne, 30th October, 1913. (Excise Tarif'[Sugar] Bill)- DENMAN, Governor-General. Message No. 18. A Bill intituled " An Act to impose a Duty of Excise upon certain Sugar," as finally passed by the Senate and the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth, having been presented to the Governor-General for the Royal Assent, His Excellency has, in the name and on behalf of His Majesty, assented to the said Act. Government House, Melbourne, 30th October, 1913. (Sugar Bounty Bill)- DENMAN, Governor-General. Message No. 19. A Bill intituled "An Act to provide for a Bounty to Growers of Sugar Cane and Beet," as finally passed by the Senate and the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth, having been presented to the Governor-General for the Royal Assent, His Excellency has, in the name and on behalf of His Majesty, assented to the said Act. -

The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918 Volume Xi Australia During the War

THE OFFICIAL HISTORY OF AUSTRALIA IN THE WAR OF 1914-1918 VOLUME XI AUSTRALIA DURING THE WAR AUSTRALIA DURING THE WAR BY ERNEST SCOTT Pmfcsor of Histow in the Vniwuty of Mdhe With 67 illustrations Sezientli Edition AUSTRALIA ANGUS AND ROBERTSON LTD. 09 CASTLEREACH STREET, SYDNEY 1941 Printed and Bcund in Australia by Halstead Press Pty Limited, 9-19 Nickson Street. Sydney. Registered at the General Post Office, Melbourne, for trana- mission through the post as a book. Obtainable in Great Britain at Australia House and from all booksellers (sole agent for wholesale distribution-The Official Secretary for the Commonwealth of Australia, Australia House, Strand, London, W C.2); in Canada from the Australian Trade Commissioner, 15 King Street West, Toronto: in the United States from the Australian Government Trade Commissioner, International Building, 630 Fifth Avenue, New York; and in New Zealand from the Australian Trade Commissioner, D.1 C. Building, Wellington. First Edtliott . , . 1936 Srroitd Edition . , 1937 Third Editioii . , . 1938 Foiirth Edition . 1939 Fifth Edition . 1939 Sixth Edition . 1940 Sewnth Edition . 1941 PREFACE THISbook is a member of a series recording the participation of the Commonwealth of Australia in the Great European War, but it differs from its companion volumes in scope and subject-matter. They are concerned with battles-in Egypt, Gallipoli, France, and Palestine; with the activities of the young Australian navy; with medical services; with the occupation of territory formerly under German government. Substantially the greater part of those works relates to what was done by Australian soldiers, sailors, medical officers, and administrators outside their own country, though on duties vitally affecting Australia and the Empire to which she belongs. -

BOOK I-AUSTRALIA at WAR CHAPTER 1 If

BOOK I-AUSTRALIA AT WAR CHAPTER 1 THE OUTBREAK OF WAR ON the 30th of June, 1914, the Australian daily newspapers contained cablegrams announcing the startling fact that two days previously the heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian empire, the Archduke Frariz Ferdinand, together with the Archduchess, had been assassiiinted at Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia, by a Serbian political desperado. The news was, of course, published under large headlines in the journals. Obviously an important event in world politics had occurred. Some serious consequences might be expected to follow. But nobody in Australia dreamt that this crime committed in the Balkans was of momentous concern for this country. If anyone had suggested that nearly 60,000 men in the prime of life and physical capacity were marked for death, and that 140,000 more would suffer maiming, as a consequence of what had happened at Sarajevo, his prediction would have seemed too absurd for credence. Where was Sarajevo? It is likely that many Australians had never even heard of the place, though memories of a school geography lesson, or study of the map of Europe, may have brought the name to the minds of a few. Shakespeare did not know where Bohemia was: in a stage direction at the head of Act 3, Scene 3, of The IVinter’s Tale, he referred to it as “Bohemia, a desert country near the sea,” though it is an inland country with no seaboard whatever. Where Shakespeare tripped we shall intend no reproach if we assume that Australians were not very well informed about a remote town in a small Balkan state. -

Biography Joseph Cook (1860-1947) Member for Parramatta (New South

James Newton Haxton Hume Cook (1866-1942) Joseph Cook (1860-1947) Member for Bourke (Victoria) 1901-1910 Member for Parramatta (New South Wales) 1901-1921 orn in Kihikihi, New Zealand, After leaving Parliament, Cook assisted orn in Silverdale, Staffordshire, England, Representatives. He was solid in his BJames Hume Cook arrived in Australia in W.M. Hughes with political activities and held BJoseph Cook migrated to the Lithgow opposition to the Protectionist Government 1881. An estate agent, Cook became involved various high-ranking positions in industrial district of New South Wales in 1885 to work behind his leader, George Reid, and grew in politics through an association with the organisations. He was made a fellow of the in the coalmines. A Methodist lay preacher increasingly estranged from the Labor Party. Australian Natives Association (ANA), and Royal Economic Society in 1936 for his for much of his adult life, he believed it his In 1908 he became Leader of the Freetrade represented East Bourke in the Victorian services to Protectionist causes on the duty to improve conditions for the working Party and in 1909 became Deputy Leader Legislative Assembly 1894-1900. He was recommendation of J.M. Keynes. Cook class from which he originated. He became and Minister for Defence in the Deakin Fusion Mayor of Brunswick, Victoria, in 1896. He was was appointed CMG in 1941. involved in union and labour movement Government. When Deakin resigned as an advocate of federation and urged the ANA activities, serving on the Labor Defence Prime Minister in 1913, Cook became leader to support the Constitution Bill produced by Committee in Lithgow during the maritime of the Liberal Party and subsequently the Australasian Federal Convention of 1897. -

Robert Scott

Family Home Page Contact Information Descendant Chart: Robert Scott Notes Persons known to be living and under age 100 are Private; only initials & surname are listed. ** indicates the source of duplication (related couple) when duplicate branches are removed from the chart. Capt. John Scott (1700-1749) & Jane Matchell (1700-?) • He was Captain of Scouts in General Wolf's army in the French and Indian War, killed while scouting disguised as Indians, by another party similarly disguised as indians under command of Lt. Washington. Caroline Lavinia Scott (1832-1892) & Pres. Benjamin Harrison (1833-1901) • He was the 23rd President of the United States, serving from 1889 to 1893. Capt. Matthew J. Scott (1739-1798) & Elizabeth Thompson (1745-1812) • He lived in the city of Philadelphia, PA, at the time of the Declaration of Independence, and was a soldier in the Revolutionary War. He was taken prisoner at the Battle of Trenton and confined on a British prison ship for 7 weeks. Louisa Welch (1842-1921) & Leopold Labrot (1842-1911) • He was the Labrot of Labrot and Graham Bourbon. In 1878, he and James Graham bought the distillery established by Elijah Pepper. They owned and operated it (except during Prohibition) until 1941, when it was sold to the Brown-Forman Corporation. Located in Versailles, KY, it is open for tours. Lucy Ware Webb (1831-1889) & Pres. Rutherford Birchard Hayes (1822-1893) • He was the 19th President of the United States, serving from 1877 to 1881. This information is provided for the use of persons engaged in non-commercial genealogical research and any commercial use whatsoever is strictly prohibited. -

Joseph Cook: the Reluctant Treasurer

Joseph Cook: the reluctant treasurer John Hawkins1 Sir Joseph Cook, somewhat reluctantly, served for 16 months as Treasurer near the end of his political career, one of two former Prime Ministers to hold the position. By then he had left his radical origins well behind him and was a very conservative Treasurer. He transferred the note issue to the Commonwealth Bank. Source: National Library of Australia. 1 At the time of writing, the author worked in the Domestic Economy Division, the Australian Treasury. The views in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Australian Treasury. 71 Joseph Cook: the reluctant treasurer Introduction Joseph Cook PC GCMG is one of only two Prime Ministers to serve as treasurer after he held the higher office.2 By some accounts he is one of the most obscure Prime Ministers.3 Cook was physically robust and hard-working, tall and strongly-built. He did not drink or swear and had ‘no time for frivolity’.4 He was uninterested in sport, dancing or music. He opposed Sunday opening of Taronga Zoo lest it distracted people from church.5 But he was known outside the parliamentary chamber for his good manners, with a cheery smile for friends and ‘a tranquillity of soul’.6 He was ‘devoted to self-improvement’.7 While from the humblest of origins, by the latter stages of his parliamentary career, ‘in manner and language, he comported himself as though born to a public school and Oxford’.8 Initially a poor speaker he trained himself to become a parliamentary dalek: it was said ‘when he started out to deal a blow to a minister … he will not desist until he has exterminated him utterly’.9 Spending most of his career in opposition, ‘the habit of a decade of criticism never left him and … he had not developed that constructive side which is so essential for both ministerial and cabinet life’10 and possessed ‘few skills in negotiation.’11 Cook spent most of his federal parliamentary career as a loyal deputy, first to Reid, then Deakin and finally Hughes. -

Supplement to the Rhode Island Colonial Records

Gc 974.5 R34ba 1774667 GENEALOGY CQLLE:CTiON ALLEN COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY 3 1833 01145 8772 SUPPLEMENT RHODE ISLAND COLONIAL RECORDS COMPRISING A LIST OF THE FREEMEN ADMITTED I AY, 174;, TO MAY, 1754. I^KOVIDENCE: SIDNEY S . RID E R 1T71667 1 1 F RHODE ISLAND (Colony) Records... 1856-65. 845 (Supplement card] .74 — \L^ Supplement to the Rhode I;island colonial ' /il\''^\l records, comprising a list of the freemen ad- mitted from. May, 1747, to May, 1754. Provi- \ L •. dence, Rider, 18^5. '! E 6975 another copy of the supplement. j ) .735 O-C^^-, i ^"^4^ tU cr^^ 8,x- NL 55-5151 RHODE ISLAND RECORDS. — RHODE ISLAND. RECORDS. LIST or. FREEMKI\: ADMITTED TO THE COLONY. TUESDAY, MAY 5tL,. 1747. The persons whose names here follow, having taken the oath or affirmation prescribed by the law of this colony against bribery and corruption, are hereby admitted to give their votes to choose officers for their respective towns, and also to give their votes for the choice of the general officers in the colony : NEWPORT. Peleg Brown, Walter Chaloner, Hczeldah Carpenter, Samuel Wickham, John Channing, Robert Carr, Walter Cranston, Nathan- iel Potter, Daniel Updike, Peter Bonrs, Godfrey Mallbone, James Honeyman, Jun'r., William Pvead, Thomas Freebody, IMathew Robinson, Lodowick Updike, Job Bennet, Jun'r., William Djre, Jim'r., Daniel Dunham, Thomas Cranston, Gideon Wanton, Sam- uel Rodman, John Easton, Serg't Daniel Goddard, Stephen Tripp, James Sheffield, Henry Taggart, Job Bennet, John Tillinghast, Thomas Wickham, Samuel Freebody, George Wanton, Philip Wil- kinson, Jonathan Tillingliast, Benjamin Hall, William Benson, Ca- leb Peckham, Joseph Wanton, Elisha Johnson, John Cranston, Thomas Richardson, Clarke Rodman, Benjamin Haszard, Kiclip- las Kaston, Jonathan Easton, Samuel Collins, Abraham Redwood, Charles Whitefield, Stephen Wanton, Peter Easton, Peleg Wood, 4 RECORDS OF THE COLONY OF RHODE ISLAND [1747. -

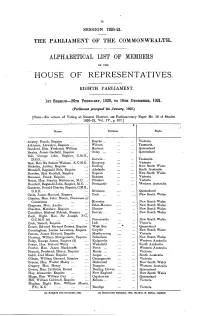

House of Representatives

SESSION 1920-21. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. ALPHABETICAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. EIGHTH PARLIAMENT. 1ST SESSION-2 6TH FEBRUARY, 1920, TO 10TH DECEMBER, 1921. (Parliament prorogued 6th January, 1922.) [NOTE-For return of Voting at General Election, see Parliamentary Paper No. 18 of Session 1920-21, Vol. IV., p. 307.] - -- ---- I--~--- ---- --- -- i- --- Name. Division. State. I--~---------------- I Anstey, Frank, Esquire Bourke ... Victoria Atkinson, Llewelyn, Esquire ... Wilmot Tasmania Bamford, Hon. Frederick William ... Herbert Queensland Bayley, James Garfield, Esquire Oxley ... Queensland Bell, George John, Esquire, C.M.G., D.S.O. ... Darwin ... Tasmania Best, Hon. Sir Robert Wallace, K.C.M.G. Kooyong Victoria Blakeley, Arthur, Esquire... Darling New South Wales Blundell, Reginald Pole, Esquire Adelaide South Australia Bowden, Eric Kendall, Esquire Nepean New South Wales Brennan, Frank, Esquire ... Batman SVictoria Bruce, Hon. Stanley Melbourne, M.C.... Flinders Victoria Burchell, Reginald John, Esquire, M.C ... Fremantle Western Australia Cameron, Donald Charles, Esquire, C.M.G., D.S.O. ... Brisbane Queensland Catts, James Howard, Esquire ... Cook ... New South Wales Chanter, Hon. John Moore, Chairman of Committees ... ... Riverina New South Wales Chapman, Hon. Austin Eden-Monaro New South Wales Charlton, Matthew, Esquire ... Hunter New South Wales Considine, Michael Patrick, Esquire ... Barrier ... New South Wales Cook, Right Hon. Sir Joseph, P.C., G.C.M.G. (a) ... ... Parramatta New South Wales Cook, Robert, Esquire ... Indi ... Victoria Corser, Edward Bernard Cresset, Esquire Wide Bay Queensland Cunningham, Lucien Lawrence, Esquire Gwydir New South Wales Fenton, James Edward, Esquire Maribyrnong Victoria Fleming, William Montgomerie, Esquire Robertson New South Wales Foley, George James, Esquire (b) Kalgoorlie Western Australia Foster, lion. -

Part 6 Combined.Pdf

MINISTRIES Showing the different Ministries since the establishment of Responsible Government; also Date of Appointment to and Retirement from Office. Name Office From To Remarks DONALDSON MINISTRY—No. 1. (6 June, 1856, to 25 August, 1856.) Stuart A. Donaldson1 .................... Colonial Secretary ...................... 6 June, 1856 25 Aug., 1856 Also referred to as Prime Minister. Thomas Holt ............................... Colonial Treasurer ..................... 6 June, 1856 25 Aug., 1856 William M. Manning1 .................. Attorney-General ....................... 6 June, 1856 25 Aug., 1856 John Bayley Darvall1 ................... Solicitor-General ........................ 6 June, 1856 25 Aug., 1856 George R. Nicholls ...................... Auditor-General ......................... 6 June, 1856 25 Aug., 1856 Also Secretary for Lands and Works during same period. William C. Mayne ....................... ................................................... 6 Aug., 1856 25 Aug., 1856 Representative of Government in Legislative Council. COWPER MINISTRY—No. 2. (26 August, 1856, to 2 October, 1856.) Charles Cowper ........................... Colonial Secretary ...................... 26 Aug., 1856 2 Oct., 1856 Also referred to as Prime Minister. Robert Campbell ......................... Colonial Treasurer ..................... 26 Aug., 1856 2 Oct., 1856 Terence A. Murray ....................... Secretary for Lands and Works .. 26 Aug., 1856 2 Oct., 1856 Also Auditor-General from 26 August to 17 September, 1856. James Martin .............................. -

DOUBLE DISSOLUTION of FEDERAL PARLIAMENT the FIFTH DOUBLE DISSOLUTION by DENIS P

DOUBLE DISSOLUTION OF FEDERAL PARLIAMENT THE FIFTH DOUBLE DISSOLUTION By DENIS P. O'BRIEN* [In this article, Mr 0'Brien examines issues arising from the recent double dissolution of Federal Parliament. First, he examines the Senate's action'. of pressing requests to the House of Representatives for amendments to Bills, and considers that this consti tutes a 'failure to pass' the Bills; and suggests that a Bill submitted to the Senate for a second time will be 'the same proposed law' as when first submitted, notwithstanding minor alterations such as the date of commencement. Secondly, he suggests that the Prime Minister'S reference to economic issues in his advice to the Governor-General that Parliament be dissolved was not properly relevant to the exercise of the Governor General's power. Finally, he examines in depth the question of whether the Governor General can exercise any independent discretion in the granting of a double dissolution, and concludes that he cannot.] A. INTRODUCTION The official correspondence between the Prime Minister, Mr Fraser, and the Governor-General, Sir Ninian Stephen, which led to the simultaneous dissolution of both Houses of the Federal Parliament on 4 February 1983 was made public by Mr Fraser on 7 February 1983 and was reproduced in the daily press on the following day. In this article an examination is made of the issues of the double dissolution. The first issue examined concerns the package of nine Sales Tax Bills which were among the thirteen Bills referred to in the Governor-General's proclamation of dissolution.1 The questions concerning the sales tax package are essentially of a legal nature. -

The Australian Standard)

(The Australian Standard) “The Standard”: The Early Years ‘A Journal to Advocate the Rights of the People in the Land.’ By Alan Katen Dunstan / November, 2005 ‘…And then, alas! The growler’s wrath most meekly sank to rest, And all his other glorious plans lay buried in his chest: Like many other growling souls, he couldn’t stand the rub, Of such a low-down, straight remark as ‘Send along a sub.’ ‘The Growler,’ or ‘Send along a sub,’ – John Farrell, 1896. With the number November 15, 1910, The Standard completed five years of publication. This was number sixty. The first issue appeared in December, 1905. To mark the event a competition was opened to find the three most successful canvassers for annual subscriptions to the paper; first prize was a copy of The Ethics of Democracy, by Louis F. Post; valued at 7s and 6d. In a second offer it was made possible to purchase every copy from No. 1 to No. 60, in bound volumes for 10s. per volume. In a flourish, not uncommon on such occasions, A.G. Huie, the editor, who first made his name with John Farrell at the Single Tax, was lavish in his praise of Joseph Hector Carruthers, an old boy of the Rockdale Branch who was then leader of the Liberal Party. Huie described Carruthers as a ‘Premier of more than ordinary courage and ability.’ The Premier’s efforts notwithstanding, when that first number appeared figures confirmed how little things had changed since the 1890s when it was first reported that New South Wales had nearly ten million acres of land locked up in the hands of just one hundred-and-eleven holders.