BOOK I-AUSTRALIA at WAR CHAPTER 1 If

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joshua Thomas Bell Queensland and the Darling Downs 1889-1911 by D

Joshua Thomas Bell Queensland and the Darling Downs 1889-1911 by D. B. Waterson Received 27 September 1984 The pastoral, legal and political career of Joshua Thomas Bell niuminates certain aspects of Queensland in general and Darling Downs history in particular during a critical time in that region's evolution. When Bell first entered the Queensland Legislative Assembly for the Northem Downs constituency of Dalby in 1893 (a seat which he was to retain until his death nineteen years later), the colony, society and landscape of the Downs were about to undergo their third major transformation since the coming of European pastoralists and the hesitant establishment of selector-based agri culture during the 1860s and 1870s. Bell's personal origins and subsequent career - he was bom in 1863 - thus spans two of the most significant phases in the European history of the region.' Bell, scion of an old-established Queensland pastoral family, now in the hands of the financially unstable Darling Downs & Westem Land Company and its overdraft master, the Queensland National Bank, entered ParUament at the time of the massive financial crash in Queensland. Yet the DarUng Downs was about to embark on a thorough reconstmction and expansion of its mral enterprises. Bell's period in Parliament saw a rapid increase in mral productivity and population on the Downs - more than in other parts of Queensland, including Brisbane - and an acceleration of Toowoomba's rise to prominence as the regional capital. The application of new tech nology, particularly in refrigeration and plant breeding, the inter vention of the State in distributing old pastoral freehold estates to Professor Duncan Waterson is Professor of History, School of History, Philosophy and Politics, Macquarie University, Sydney. -

1835. EXECUTIVE. *L POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT

1835. EXECUTIVE. *l POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT. Persons employed in the General Post Office, with the annual compensation of each. Where Compen Names. Offices. Born. sation. Dol. cts. Amos Kendall..., Postmaster General.... Mass. 6000 00 Charles K. Gardner Ass't P. M. Gen. 1st Div. N. Jersey250 0 00 SelahR. Hobbie.. Ass't P. M. Gen. 2d Div. N. York. 2500 00 P. S. Loughborough Chief Clerk Kentucky 1700 00 Robert Johnson. ., Accountant, 3d Division Penn 1400 00 CLERKS. Thomas B. Dyer... Principal Book Keeper Maryland 1400 00 Joseph W. Hand... Solicitor Conn 1400 00 John Suter Principal Pay Clerk. Maryland 1400 00 John McLeod Register's Office Scotland. 1200 00 William G. Eliot.. .Chie f Examiner Mass 1200 00 Michael T. Simpson Sup't Dead Letter OfficePen n 1200 00 David Saunders Chief Register Virginia.. 1200 00 Arthur Nelson Principal Clerk, N. Div.Marylan d 1200 00 Richard Dement Second Book Keeper.. do.. 1200 00 Josiah F.Caldwell.. Register's Office N. Jersey 1200 00 George L. Douglass Principal Clerk, S. Div.Kentucky -1200 00 Nicholas Tastet Bank Accountant Spain. 1200 00 Thomas Arbuckle.. Register's Office Ireland 1100 00 Samuel Fitzhugh.., do Maryland 1000 00 Wm. C,Lipscomb. do : for) Virginia. 1000 00 Thos. B. Addison. f Record Clerk con-> Maryland 1000 00 < routes and v....) Matthias Ross f. tracts, N. Div, N. Jersey1000 00 David Koones Dead Letter Office Maryland 1000 00 Presley Simpson... Examiner's Office Virginia- 1000 00 Grafton D. Hanson. Solicitor's Office.. Maryland 1000 00 Walter D. Addison. Recorder, Div. of Acc'ts do.. -

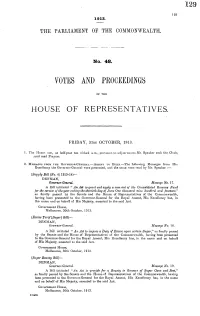

Votes and Proceedings

129 129 1913. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. No. 48. VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. FRIDAY, 31ST OCTOBER, 1913. 1. The H[ou, mielt, at half-past ten o'clock a.m., puirsunt to adjourniiniit.Mr. Speaker took the Chair, .and read Prayers. 2. MESSAGES FROM THE GOVERNOR-GENERAL.-ASSENT TO BILLS.-The following Messages from His Excellency the Governor-General were presented, and the same were read by IMr.Speaker :- (Supply Bill (No. 4) 1913-14)-- DENMAN, Governor-General. Message No. 17. A Bill intituled " An Act to grant and apply a sum out of the Consolidated Revenue Fund for the service of the year ending the thirtieth day of June One thousand nine hundred and fourteen," as finally passed by the Senate and the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth, having been presented to the -Governor-General for the Royal Assent, His Excellency has, in the name and on behalf of His Majesty, assented to the said Act. Government House, Melbourne, 30th October, 1913. (Excise Tarif'[Sugar] Bill)- DENMAN, Governor-General. Message No. 18. A Bill intituled " An Act to impose a Duty of Excise upon certain Sugar," as finally passed by the Senate and the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth, having been presented to the Governor-General for the Royal Assent, His Excellency has, in the name and on behalf of His Majesty, assented to the said Act. Government House, Melbourne, 30th October, 1913. (Sugar Bounty Bill)- DENMAN, Governor-General. Message No. 19. A Bill intituled "An Act to provide for a Bounty to Growers of Sugar Cane and Beet," as finally passed by the Senate and the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth, having been presented to the Governor-General for the Royal Assent, His Excellency has, in the name and on behalf of His Majesty, assented to the said Act. -

House of Representatives By-Elections 1902-2002

INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND ADVICE FOR THE PARLIAMENT INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES Current Issues Brief No. 15 2002–03 House of Representatives By-elections 1901–2002 DEPARTMENT OF THE PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY ISSN 1440-2009 Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2003 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department of the Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament in the course of their official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribution to Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced, the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian government document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staff but not with members of the public. Published by the Department of the Parliamentary Library, 2003 I NFORMATION AND R ESEARCH S ERVICES Current Issues Brief No. 15 2002–03 House of Representatives By-elections 1901–2002 Gerard Newman, Statistics Group Scott Bennett, Politics and Public Administration Group 3 March 2003 Acknowledgments The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Murray Goot, Martin Lumb, Geoff Winter, Jan Pearson, Janet Wilson and Diane Hynes in producing this paper. -

Earle Page and the Imagining of Australia

‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA ‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA STEPHEN WILKS Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, Or what’s a heaven for? Robert Browning, ‘Andrea del Sarto’ The man who makes no mistakes does not usually make anything. Edward John Phelps Earle Page as seen by L.F. Reynolds in Table Talk, 21 October 1926. Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760463670 ISBN (online): 9781760463687 WorldCat (print): 1198529303 WorldCat (online): 1198529152 DOI: 10.22459/NPM.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This publication was awarded a College of Arts and Social Sciences PhD Publication Prize in 2018. The prize contributes to the cost of professional copyediting. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: Earle Page strikes a pose in early Canberra. Mildenhall Collection, NAA, A3560, 6053, undated. This edition © 2020 ANU Press CONTENTS Illustrations . ix Acknowledgements . xi Abbreviations . xiii Prologue: ‘How Many Germans Did You Kill, Doc?’ . xv Introduction: ‘A Dreamer of Dreams’ . 1 1 . Family, Community and Methodism: The Forging of Page’s World View . .. 17 2 . ‘We Were Determined to Use Our Opportunities to the Full’: Page’s Rise to National Prominence . -

The Importance of Boundaries

The importance of boundaries Colin Hughes Emeritus Professor of Politic Science, University of Queensland Research Paper 1 (November 2007) Democratic Audit of Australia Australian National University Canberra, ACT 0200 Australia http://democratic.audit.anu.edu.au The views expressed are the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Democratic Audit of Australia. If elections are to be thought fair, their outcomes should correspond as closely as possible to the inputs of voter preferences. A particular percentage of the votes counted for a party should produce close to the same percentage of the seats won by that party. Down that path lie the topics of partisan bias and proportional representation with multi-member electoral districts as the most common solution. But there is a second criterion of fairness which is that outcomes should correspond to the numbers of electors or people to be represented. That criterion is often called equality, and down that path lie the topics of malapportionment and enforced equality as a solution. The two criteria may not work in the same direction.1 In Australia the problem of equality has been debated mainly with respect to the dichotomy of town and country, ‘town’ usually meaning the State capital(s) which have been invariably by far the largest urban center in each State and ‘country’ the rest, though sometimes the larger provincial cities and towns get lumped in with their local metropolis. Should town voters have the same quantity of representation, measured by the number of electors in the electoral districts, as country voters? There has also been a sub-plot, which is what this paper is about, that concerns the existence of a small number of electoral districts spread over exceptionally large areas in which the population, and consequently the numbers of electors, is relatively thin on the ground and widely scattered. -

House of Representatives By-Elections 1901-2005

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services Parliamentary Library RESEARCH BRIEF Information analysis and advice for the Parliament 16 August 2005, no. 1, 2005–06, ISSN 1832-2883 House of Representatives by-elections 1901–2005 The first part of this revised brief discusses the 141 by-elections for the House of Representatives since Federation, including the most recent for the New South Wales division of Werriwa. The brief’s appendices give a full set of by-election figures. Gerard Newman, Statistics Section Scott Bennett, Politics and Public Administration Section Contents Party abbreviations ................................................... 1 Executive summary ................................................... 2 Contests ......................................................... 2 Causes .......................................................... 2 Outcomes ........................................................ 2 The organisation of Commonwealth by-elections.............................. 3 The reasons why by-elections have been held .............................. 3 The timing of by-elections ............................................ 4 By-elections 1994–05 ............................................. 5 Vacancies for which no by-election was held 1901–2005 ................... 6 Number of nominations .............................................. 6 Candidates per by-election ......................................... 7 Voter turnout ..................................................... 7 Party performance ................................................... -

The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918 Volume Xi Australia During the War

THE OFFICIAL HISTORY OF AUSTRALIA IN THE WAR OF 1914-1918 VOLUME XI AUSTRALIA DURING THE WAR AUSTRALIA DURING THE WAR BY ERNEST SCOTT Pmfcsor of Histow in the Vniwuty of Mdhe With 67 illustrations Sezientli Edition AUSTRALIA ANGUS AND ROBERTSON LTD. 09 CASTLEREACH STREET, SYDNEY 1941 Printed and Bcund in Australia by Halstead Press Pty Limited, 9-19 Nickson Street. Sydney. Registered at the General Post Office, Melbourne, for trana- mission through the post as a book. Obtainable in Great Britain at Australia House and from all booksellers (sole agent for wholesale distribution-The Official Secretary for the Commonwealth of Australia, Australia House, Strand, London, W C.2); in Canada from the Australian Trade Commissioner, 15 King Street West, Toronto: in the United States from the Australian Government Trade Commissioner, International Building, 630 Fifth Avenue, New York; and in New Zealand from the Australian Trade Commissioner, D.1 C. Building, Wellington. First Edtliott . , . 1936 Srroitd Edition . , 1937 Third Editioii . , . 1938 Foiirth Edition . 1939 Fifth Edition . 1939 Sixth Edition . 1940 Sewnth Edition . 1941 PREFACE THISbook is a member of a series recording the participation of the Commonwealth of Australia in the Great European War, but it differs from its companion volumes in scope and subject-matter. They are concerned with battles-in Egypt, Gallipoli, France, and Palestine; with the activities of the young Australian navy; with medical services; with the occupation of territory formerly under German government. Substantially the greater part of those works relates to what was done by Australian soldiers, sailors, medical officers, and administrators outside their own country, though on duties vitally affecting Australia and the Empire to which she belongs. -

Private LITTLETON CAMPBELL GROOM

In Memory of Private LITTLETON CAMPBELL GROOM 1843, 42nd Bn Australian Infantry, A.I.F. who died age 28 on 10th June 1917 Son of Frederick William and Fanny Matilda Groom, of "Lorriane," Herries St., Toowoomba, Queensland. Remembered with honour BETHLEEM FARM EAST CEMETERY, BELGIUM PRIVATE LITTLETON CAMPBELL GROOM 42ND BN, AUSTRALIAN INFANTRY SERVICE NUMBER: 1843 Littleton Campbell Groom enlisted in Toowoomba on 19 February 1916 two months after his twenty-seventh birthday. He gave his occupation as newspaper reporter and was employed on the family- owned Toowoomba Chronicle. After the war his father stated he was the paper’s sub-editor. Littleton carried one of the family names, his uncle Littleton Ernest Groom being Member for the Darling Downs (MHR) and a minister in the Federal Government. Following a custom of the time, the name “Littleton” was from his grandmother’s maiden name. Littleton junior’s parents were Frederick William and Fanny Matilda Groom of Herries Street, Toowoomba. He was born and educated in the city, attending state schools and the Christian Brothers College. Littleton was of the Church of England religion. He was 5’8” tall, weighed 140 pounds and had a fair complexion, brown eyes and brown hair. After basic training he was posted to the new 42nd Battalion at the Artillery Camp at Enoggera and embarked for overseas service in Brisbane aboard A42 Boorara on 10 June 1916. Littleton continued training in England where the 42nd was based as part of the 3rd Division, the newest and last of five divisions to join the AIF on the Western Front. -

Biography Joseph Cook (1860-1947) Member for Parramatta (New South

James Newton Haxton Hume Cook (1866-1942) Joseph Cook (1860-1947) Member for Bourke (Victoria) 1901-1910 Member for Parramatta (New South Wales) 1901-1921 orn in Kihikihi, New Zealand, After leaving Parliament, Cook assisted orn in Silverdale, Staffordshire, England, Representatives. He was solid in his BJames Hume Cook arrived in Australia in W.M. Hughes with political activities and held BJoseph Cook migrated to the Lithgow opposition to the Protectionist Government 1881. An estate agent, Cook became involved various high-ranking positions in industrial district of New South Wales in 1885 to work behind his leader, George Reid, and grew in politics through an association with the organisations. He was made a fellow of the in the coalmines. A Methodist lay preacher increasingly estranged from the Labor Party. Australian Natives Association (ANA), and Royal Economic Society in 1936 for his for much of his adult life, he believed it his In 1908 he became Leader of the Freetrade represented East Bourke in the Victorian services to Protectionist causes on the duty to improve conditions for the working Party and in 1909 became Deputy Leader Legislative Assembly 1894-1900. He was recommendation of J.M. Keynes. Cook class from which he originated. He became and Minister for Defence in the Deakin Fusion Mayor of Brunswick, Victoria, in 1896. He was was appointed CMG in 1941. involved in union and labour movement Government. When Deakin resigned as an advocate of federation and urged the ANA activities, serving on the Labor Defence Prime Minister in 1913, Cook became leader to support the Constitution Bill produced by Committee in Lithgow during the maritime of the Liberal Party and subsequently the Australasian Federal Convention of 1897. -

Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Twenty-Four

Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Twenty-four Proceedings of the Twenty-fourth Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society Traders Hotel Brisbane, 159 Roma Street, Hobart — August 2012 © Copyright 2014 by The Samuel Griffith Society. All rights reserved. Contents Introduction Julian Leeser The Fourth Sir Harry Gibbs Memorial Oration Senator the Honourable George Brandis In Defence of Freedom of Speech Chapter One The Honourable Ian Callinan Defamation, Privacy, the Finkelstein Report and the Regulation of the Media Chapter Two Michael Sexton Flights of Fancy: The Implied Freedom of Political Communication 20 Years On Chapter Three The Honourable Justice J. D. Heydon Sir Samuel Griffith and the Making of the Australian Constitution Chapter Four The Honourable Christian Porter Federal-State Relations and the Changing Economy Chapter Five The Honourable Richard Court A Federalist Agenda for Coast to Coast Liberal (or Labor) Governments Chapter Six Keith Kendall The Case for a State Income Tax Chapter Seven Josephine Kelly The Constitutionality of the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act i Chapter Eight The Honourable Gary Johns Native Title 20 Years On: Beyond the Hyperbole Chapter Nine Lorraine Finlay Indigenous Recognition – Some Issues Chapter Ten J. B. Paul Speaker of the House Contributors ii Introduction Julian Leeser The 24th Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society was held in Brisbane during the weekend of 17-19 August 2012. It marked the 20th anniversary of the Society’s birth. 1992 was undoubtedly a momentous year in Australia’s constitutional history. On 2 January 1992 the perspicacious John and Nancy Stone decided to incorporate the Samuel Griffith Society thirteen days after Paul Keating was appointed Prime Minister. -

Selected Australian Political Records

RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2013–14 UPDATED 5 MARCH 2014 Selected political records of the Commonwealth Parliament Martin Lumb and Rob Lundie Politics and Public Administration Contents Introduction ................................................................................................ 6 Governor-General ....................................................................................... 6 First Governor-General..................................................................................... 6 First Australian-born Governor-General .......................................................... 6 Prime Ministers ........................................................................................... 6 First Prime Minister .......................................................................................... 6 First Leader of the Opposition .......................................................................... 6 Youngest person to become Prime Minister .................................................... 6 Oldest person to become Prime Minister ........................................................ 6 Longest serving Prime Minister ........................................................................ 6 Shortest serving Prime Minister ....................................................................... 6 Oldest serving Prime Minister .......................................................................... 6 Prime Ministers who served separate terms as Prime Minister ...................... 6 Prime Ministers who