Governments, Parliaments and Parties (Australia) | International

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Attitudes to Conscription: 1914–1918

RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2016–17 27 OCTOBER 2016 Political attitudes to conscription: 1914–1918 Dr Nathan Church Foreign Affairs, Defence and Security Section Contents Introduction ................................................................................................ 2 Attitudes of the Australian Labor Party ........................................................ 2 Federal government ......................................................................................... 2 New South Wales ............................................................................................. 7 Victoria ............................................................................................................. 8 Queensland ...................................................................................................... 9 Western Australia ........................................................................................... 10 South Australia ............................................................................................... 11 Political impact on the ALP ............................................................................... 11 Attitudes of the Commonwealth Liberal Party ............................................. 12 Attitudes of the Nationalist Party of Australia ............................................. 13 The second conscription plebiscite .................................................................. 14 Conclusion ................................................................................................ -

1835. EXECUTIVE. *L POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT

1835. EXECUTIVE. *l POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT. Persons employed in the General Post Office, with the annual compensation of each. Where Compen Names. Offices. Born. sation. Dol. cts. Amos Kendall..., Postmaster General.... Mass. 6000 00 Charles K. Gardner Ass't P. M. Gen. 1st Div. N. Jersey250 0 00 SelahR. Hobbie.. Ass't P. M. Gen. 2d Div. N. York. 2500 00 P. S. Loughborough Chief Clerk Kentucky 1700 00 Robert Johnson. ., Accountant, 3d Division Penn 1400 00 CLERKS. Thomas B. Dyer... Principal Book Keeper Maryland 1400 00 Joseph W. Hand... Solicitor Conn 1400 00 John Suter Principal Pay Clerk. Maryland 1400 00 John McLeod Register's Office Scotland. 1200 00 William G. Eliot.. .Chie f Examiner Mass 1200 00 Michael T. Simpson Sup't Dead Letter OfficePen n 1200 00 David Saunders Chief Register Virginia.. 1200 00 Arthur Nelson Principal Clerk, N. Div.Marylan d 1200 00 Richard Dement Second Book Keeper.. do.. 1200 00 Josiah F.Caldwell.. Register's Office N. Jersey 1200 00 George L. Douglass Principal Clerk, S. Div.Kentucky -1200 00 Nicholas Tastet Bank Accountant Spain. 1200 00 Thomas Arbuckle.. Register's Office Ireland 1100 00 Samuel Fitzhugh.., do Maryland 1000 00 Wm. C,Lipscomb. do : for) Virginia. 1000 00 Thos. B. Addison. f Record Clerk con-> Maryland 1000 00 < routes and v....) Matthias Ross f. tracts, N. Div, N. Jersey1000 00 David Koones Dead Letter Office Maryland 1000 00 Presley Simpson... Examiner's Office Virginia- 1000 00 Grafton D. Hanson. Solicitor's Office.. Maryland 1000 00 Walter D. Addison. Recorder, Div. of Acc'ts do.. -

Strategy-To-Win-An-Election-Lessons

WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 i The Institute of International Studies (IIS), Department of International Relations, Universitas Gadjah Mada, is a research institution focused on the study on phenomenon in international relations, whether on theoretical or practical level. The study is based on the researches oriented to problem solving, with innovative and collaborative organization, by involving researcher resources with reliable capacity and tight society social network. As its commitments toward just, peace and civility values through actions, reflections and emancipations. In order to design a more specific and on target activity, The Institute developed four core research clusters on Globalization and Cities Development, Peace Building and Radical Violence, Humanitarian Action and Diplomacy and Foreign Policy. This institute also encourages a holistic study which is based on contempo- rary internationalSTRATEGY relations study scope TO and WIN approach. AN ELECTION: ii WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 By Dafri Agussalim INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS UNIVERSITAS GADJAH MADA iii WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 Penulis: Dafri Agussalim Copyright© 2011, Dafri Agussalim Cover diolah dari: www.biogenidec.com dan http:www.foto.detik.com Diterbitkan oleh Institute of International Studies Jurusan Ilmu Hubungan Internasional, Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik Universitas Gadjah Mada Cetakan I: 2011 x + 244 hlm; 14 cm x 21 cm ISBN: 978-602-99702-7-2 Fisipol UGM Gedung Bulaksumur Sayap Utara Lt. 1 Jl. Sosio-Justisia, Bulaksumur, Yogyakarta 55281 Telp: 0274 563362 ext 115 Fax.0274 563362 ext.116 Website: http://www.iis-ugm.org E-mail: [email protected] iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book is a revised version of my Master of Arts (MA) thesis, which was written between 1994-1995 in the Australian National University, Canberra Australia. -

Some Aspects of the Federal Political Career of Andrew Fisher

SOME ASPECTS OF THE FEDERAL POLITICAL CAREER OF ANDREW FISHER By EDWARD WIL.LIAM I-IUMPHREYS, B.A. Hans. MASTER OF ARTS Department of History I Faculty of Arts, The University of Melbourne Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degr'ee of Masters of Arts (by Thesis only) JulV 2005 ABSTRACT Andrew Fisher was prime minister of Australia three times. During his second ministry (1910-1913) he headed a government that was, until the 1940s, Australia's most reformist government. Fisher's second government controlled both Houses; it was the first effective Labor administration in the history of the Commonwealth. In the three years, 113 Acts were placed on the statute books changing the future pattern of the Commonwealth. Despite the volume of legislation and changes in the political life of Australia during his ministry, there is no definitive full-scale biographical published work on Andrew Fisher. There are only limited articles upon his federal political career. Until the 1960s most historians considered Fisher a bit-player, a second ranker whose main quality was his moderating influence upon the Caucus and Labor ministry. Few historians have discussed Fisher's role in the Dreadnought scare of 1909, nor the background to his attempts to change the Constitution in order to correct the considered deficiencies in the original drafting. This thesis will attempt to redress these omissions from historical scholarship Firstly, it investigates Fisher's reaction to the Dreadnought scare in 1909 and the reasons for his refusal to agree to the financing of the Australian navy by overseas borrowing. -

To the William Howard Taft Papers. Volume 1

THE L I 13 R A R Y 0 F CO 0.: G R 1 ~ ~ ~ • P R I ~ ~ I I) I ~ \J T ~' PAP E R ~ J N 1) E X ~ E R IE S INDEX TO THE William Howard Taft Papers LIBRARY OF CONGRESS • PRESIDENTS' PAPERS INDEX SERIES INDEX TO THE William Ho-ward Taft Papers VOLUME 1 INTRODUCTION AND PRESIDENTIAL PERIOD SUBJECT TITLES MANUSCRIPT DIVISION • REFERENCE DEPARTMENT LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON : 1972 Library of Congress 'Cataloging in Publication Data United States. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. Index to the William Howard Taft papers. (Its Presidents' papers index series) 1. Taft, William Howard, Pres. U.S., 1857-1930. Manuscripts-Indexes. I. Title. II. Series. Z6616.T18U6 016.97391'2'0924 70-608096 ISBN 0-8444-0028-9 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $24 per set. Sold in'sets only. Stock Number 3003-0010 Preface THIS INDEX to the William Howard Taft Papers is a direct result of the wish of the Congress and the President, as expressed by Public Law 85-147 approved August 16, 1957, and amended by Public Laws 87-263 approved September 21, 1961, and 88-299 approved April 27, 1964, to arrange, index, and microfilm the papers of the Presidents in the Library of Congress in order "to preserve their contents against destruction by war or other calamity," to make the Presidential Papers more "readily available for study and research," and to inspire informed patriotism. Presidents whose papers are in the Library are: George Washington James K. -

Andrew FISHER, PC Prime Minister 13 November 1908 to 2 June 1909; 29 April 1910 to 24 June 1913; 17 September 1914 to 27 October 1915

5 Andrew FISHER, PC Prime Minister 13 November 1908 to 2 June 1909; 29 April 1910 to 24 June 1913; 17 September 1914 to 27 October 1915. Andrew Fisher became the 5th prime minister when the Liberal- Labor coalition government headed by Alfred Deakin collapsed due to loss of parliamentary Labor support. Fisher’s first period as prime minister ended when the new Fusion Party of Deakin and Joseph Cook defeated the government in parliament. His second term resulted from an overwhelming Labor victory at elections in 1910. However, Labor lost power by one seat at the 1913 elections. Fisher was prime minister again in 1914, as a result of a double-dissolution election. Fisher resigned from office in October 1915, his health affected by the pressures of political life. Member of the Australian Labor Party c1901-28. Member of the House of Representatives for the seat of Wide Bay (Queensland) 1901-15; Minister for Trade and Customs 1904; Treasurer 1908-09, 1910-13, 1914-15. Main achievements (1904-1915) Under his prime ministership, the Commonwealth Government issued its first currency which replaced bank and State currency as the only legal tender. Also, the Commonwealth Bank was established. Strengthened the Conciliation and Arbitration Act. Introduced a progressive land tax on unimproved properties. Construction began on the trans-Australian railway, linking Port Augusta and Kalgoorlie. Established the Australian Capital Territory and brought the Northern Territory under Commonwealth control. Established the Royal Australian Navy. Improved access to invalid and aged pensions and brought in maternity allowances. Introduced workers’ compensation for federal public servants. -

And Where He Did

Vol. 2 No. 9 October 1992 $4.00 and where he did Volume 2 Number 9 I:URI:-KA STRI:-eT October 1992 A m agazine of public affairs, the arts and theology 21 CoNTENTS TOPGUN Michael McGirr reports on gun laws and the calls for capital punishment in the 4 Philippines. COMMENT In this year of elections we are only as good 22 as our choices, says Peter Steele. Andrew DON'T KISS ME, HARDY Hamilton looks at the Columbus quin James Griffin concludes his series on the centary, and decides that the past must be Wren-Evatt letters. owned as well as owned up to (pS). 6 25 ORIENTATIONS LETTERS Peter Pierce and Robin Gerster take their pens to Shanghai and Saigon; Emmanuel 7 Santos and Hwa Goh take their cameras to COMMISSIONS AND OMISSIONS Tianjin. ICAC chief Ian Temby Margaret Simons talks to Australia's top speaks for himself: p 7 crime-busters. 34 11 BOOKS AND ARTS Cover photo: A member of Was the oldest part of the Pentateuch CAPITAL LETTER the Tianjing city planning office written by a woman? Kevin Hart reviews in Jei Fang Bei Road, three books by Harold Bloom, who thinks the 'Wall Street' of Tianjin. 12 it was; Robert Murray sizes up Columbus BLINDED BY THE LIGHT and colonialism (p38 ). Cover photo and photos pp25, 29 and 30 Bruce Williams visits the Columbus light by Emmanuel Santos; house in Santo Domingo, and wonders who Photo p27 by Hwa Goh; will be enlightened. 40 Photos p12 by Belinda Bain; FLASH IN THE PAN Photo p41 by Bill Thomas; 15 Reviews of the films Patriot Games Cartoons pp6, 36 and 3 7 by Dean Moore; Zentropa, Edward II, and Deadly. -

Ben Chifley: the True Believer1

1 Ben Chifley: the true believer John Hawkins2 Chifley was a ‘true believer’ in the Labor Party and in the role that government could play in stabilising the economy and keeping unemployment low. He was an active treasurer, initially working well with Prime Minister Curtin and then serving as both Prime Minister and Treasurer himself. He managed the war economy competently and achieved a smooth transition to a peacetime economy, although he allowed inflationary pressures to build up in the post-war years. Among his economic reforms were increased welfare payments, uniform income taxation and developing central banking powers (through direct controls rather than market mechanisms) for the Commonwealth Bank. Source: National Library of Australia.3 1 Arthur Fadden served almost a year as treasurer before Chifley, but as Chifley was Treasurer for most of the 1940s and Fadden for most of the 1950s, the essay on Chifley is being presented first in this series. 2 The author formerly worked in the Domestic Economy Division, the Australian Treasury. This article has benefited from comments provided by Selwyn Cornish, Robin McLachlan, Sam Malloy and Richard Grant. Thanks are also extended to the staff of the Chifley Home in Bathurst. The views in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Australian Treasury. 103 Ben Chifley: the true believer Introduction The Right Honorable Joseph Benedict Chifley was a ‘true believer’ in the Labor cause.4 While an idealist, remembered for coining the term 'light on the hill' to capture -

CHAPTER SI1 IF the Prime Minister's Assertion of The

CHAPTER SI1 THE LAST MONTHS OF THE WAR IF the Prime Minister’s assertion of the intention of his Government-to “ decline to take responsibility for the conduct of public affairs ” unless given power to secure re- inforcements by compulsion-had been less emphatic, and had contained a convenient conditional phrase, the political predicaiiient caused by the referendum of 1917 would have been avoided. But it was a peculiarly hard and fast declara- tion, without the semblance of a limitation. Similar declara- tions were made by other members of the ministry. hir. Hughes’s “ Merry Christmas,” at his country home in the Dandenong Ranges a few days after the referendum, was therefore marred by the prospect of having to carry out his pledge by placing his resignation in the hands of the Governor-General. Ministers and members of Parliament spent the traditional Season of “peace and good will,” both of which were con- spicuously deficient at this time, at their homes, but in the first week of a hot Melbourne January they began to gather at the seat of government. Parliament was to meet in the second week of that month. Speculation as to what would happen kept political circles agog. Would Mr. Hughes resign after all ? Would the Nationalist party insist upon keeping him to his undertaking? Would the whole ministry retire and give place to a fresh combination? If so, who would succeed as Prime Minister? During the opening days of thc new year there glimmered upon the horizon a streak which seemed to preqage storm. Sir John Forrest was reported--and the report was not afterwards denied--to be in disagreement with his colleagues, and there were com- mentators in the Nationalist journals who expressed doubts about Mr. -

Whitlam's Children? Labor and the Greens in Australia (2007-2013

Whitlam’s Children? Labor and the Greens in Australia (2007-2013) Shaun Crowe A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University March 2017 © Shaun Crowe, 2017 1 The work presented in this dissertation is original, to the best of my knowledge and belief, except as acknowledged in the text. The material has not been submitted, in whole or in part, for a degree at The Australian National University or any other university. This research is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship. 2 Acknowledgments Before starting, I was told that completing a doctoral thesis was rewarding and brutal. Having now written one, these both seem equally true. Like all PhD students, I never would have reached this point without the presence, affirmation and help of the people around me. The first thanks go to Professor John Uhr. Four and half years on, I’m so lucky to have stumbled into your mentorship. With such a busy job, I don’t know how you find the space to be so generous, both intellectually and with your time. Your prompt, at times cryptic, though always insightful feedback helped at every stage of the process. Even more useful were the long and digressive conversations in your office, covering the world between politics and philosophy. I hope they continue. The second round of thanks go to the people who aided me at different points. Thanks to Guy Ragen, Dr Jen Rayner and Alice Workman for helping me source interviews. Thanks to Emily Millane, Will Atkinson, Dr Lizzy Watt, and Paul Karp for editing chapters. -

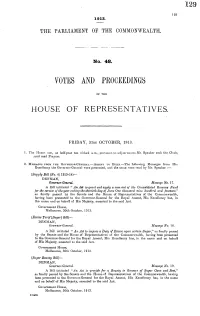

Votes and Proceedings

129 129 1913. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. No. 48. VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. FRIDAY, 31ST OCTOBER, 1913. 1. The H[ou, mielt, at half-past ten o'clock a.m., puirsunt to adjourniiniit.Mr. Speaker took the Chair, .and read Prayers. 2. MESSAGES FROM THE GOVERNOR-GENERAL.-ASSENT TO BILLS.-The following Messages from His Excellency the Governor-General were presented, and the same were read by IMr.Speaker :- (Supply Bill (No. 4) 1913-14)-- DENMAN, Governor-General. Message No. 17. A Bill intituled " An Act to grant and apply a sum out of the Consolidated Revenue Fund for the service of the year ending the thirtieth day of June One thousand nine hundred and fourteen," as finally passed by the Senate and the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth, having been presented to the -Governor-General for the Royal Assent, His Excellency has, in the name and on behalf of His Majesty, assented to the said Act. Government House, Melbourne, 30th October, 1913. (Excise Tarif'[Sugar] Bill)- DENMAN, Governor-General. Message No. 18. A Bill intituled " An Act to impose a Duty of Excise upon certain Sugar," as finally passed by the Senate and the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth, having been presented to the Governor-General for the Royal Assent, His Excellency has, in the name and on behalf of His Majesty, assented to the said Act. Government House, Melbourne, 30th October, 1913. (Sugar Bounty Bill)- DENMAN, Governor-General. Message No. 19. A Bill intituled "An Act to provide for a Bounty to Growers of Sugar Cane and Beet," as finally passed by the Senate and the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth, having been presented to the Governor-General for the Royal Assent, His Excellency has, in the name and on behalf of His Majesty, assented to the said Act. -

Economic Roundup

Economic Roundup Issue 4, 2008 © Commonwealth of Australia 2008 ISBN 978-0-642-74489-0 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Commonwealth Copyright Administration Attorney-General’s Department Robert Garran Offices National Circuit CANBERRA ACT 2600 Or posted at: http://www.ag.gov.au/cca The views expressed in the Economic Roundup are commentary only, and should not be considered as advice. You should not act in reliance upon the views expressed in the publication, but should seek independent professional advice in relation to these issues and any proposed actions. The Commonwealth and the authors disclaim responsibility for loss or damage suffered by any person relying, directly or indirectly, on this publication, including in relation to negligence or any other default. Internet A copy of this document appears on the Treasury website at: www.treasury.gov.au Purchasing copies Over the counter at: 16 Nyrang Street, Fyshwick ACT Canprint Telesales: Toll Free 1300 889 873 (Operator service available between 8 am and 5 pm AEST weekdays. Message facility available for after hours calls.) Canprint Mail Order Sales: PO Box 7456 Canberra MC ACT 2610 By email at: [email protected] Printed by Canprint Communications Pty Limited CONTENTS Towards a tax and transfer system of human scale 1 The smarter use of data 11