The English in Sydney

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frequently Asked Questions & Answers Reopening East West

Frequently Asked Questions & Answers Reopening East West Runway Q: How many runways does Sydney Airport have? A: Sydney Airport has three runways: • East-west runway, also known as runway 07/25 • Main north-south runway, also known as runway 16R/34L • Parallel north-south runway, also known as runway 16L/34R Q: When are the three runways typically used? A: The Australian Government agency responsible for air traffic control – Airservices Australia – manages runway usage to ensure safety. Weather – especially wind direction and strength and rain – is a major factor in deciding which runways can be safely used for take-off and landing. Aircraft generally take-off and land into the wind, or with minimal tail wind. Based on wind direction, air traffic control will decide which runway is used at any given time. However, the decision to take-off or land ultimately rests with the pilot-in-command of the aircraft. Q: What is “noise sharing” and how is it implemented? A: At Sydney Airport, the Australian Government’s noise sharing policy – known as the Long Term Operating Plan, or LTOP – also influences when a particular runway is used. The LTOP is a program to manage aircraft noise from Sydney Airport. It aims to make sure flights are sent over water and non-residential land, as much as possible. Where this is not possible, it aims to share noise across communities in Sydney and provide periods of respite from noise. It provides ten different ways of using the airport’s three runways and associated flight paths, some of which involve use of the east-west runway. -

1835. EXECUTIVE. *L POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT

1835. EXECUTIVE. *l POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT. Persons employed in the General Post Office, with the annual compensation of each. Where Compen Names. Offices. Born. sation. Dol. cts. Amos Kendall..., Postmaster General.... Mass. 6000 00 Charles K. Gardner Ass't P. M. Gen. 1st Div. N. Jersey250 0 00 SelahR. Hobbie.. Ass't P. M. Gen. 2d Div. N. York. 2500 00 P. S. Loughborough Chief Clerk Kentucky 1700 00 Robert Johnson. ., Accountant, 3d Division Penn 1400 00 CLERKS. Thomas B. Dyer... Principal Book Keeper Maryland 1400 00 Joseph W. Hand... Solicitor Conn 1400 00 John Suter Principal Pay Clerk. Maryland 1400 00 John McLeod Register's Office Scotland. 1200 00 William G. Eliot.. .Chie f Examiner Mass 1200 00 Michael T. Simpson Sup't Dead Letter OfficePen n 1200 00 David Saunders Chief Register Virginia.. 1200 00 Arthur Nelson Principal Clerk, N. Div.Marylan d 1200 00 Richard Dement Second Book Keeper.. do.. 1200 00 Josiah F.Caldwell.. Register's Office N. Jersey 1200 00 George L. Douglass Principal Clerk, S. Div.Kentucky -1200 00 Nicholas Tastet Bank Accountant Spain. 1200 00 Thomas Arbuckle.. Register's Office Ireland 1100 00 Samuel Fitzhugh.., do Maryland 1000 00 Wm. C,Lipscomb. do : for) Virginia. 1000 00 Thos. B. Addison. f Record Clerk con-> Maryland 1000 00 < routes and v....) Matthias Ross f. tracts, N. Div, N. Jersey1000 00 David Koones Dead Letter Office Maryland 1000 00 Presley Simpson... Examiner's Office Virginia- 1000 00 Grafton D. Hanson. Solicitor's Office.. Maryland 1000 00 Walter D. Addison. Recorder, Div. of Acc'ts do.. -

Constructing Time and Space in the Garden Suburb

1 Constructing Time and Space in the Garden Suburb lon Hoskins Allan Ashbolt began his contribution to Me anj in' s 1,9 6 6' G o dzone' symposium with a portrayal of Australian 'reality': Behold the man-the Australian of today-on Sunday morn- ings in the suburbs, when the high decibel drone of the motor- mower is calling the faithful to worship. A block of land, a brick veneer, and the motor-mower beside him in the wilder- ness-what more does he want to sustain him. In Ashbolt's suburbia we have wilderness and garden, the pioneer and his Victa, linked-albeit ironically-to material and spiritual sustenance. The mowers proceed to drown out 'the plaintive clanging of the church-bells . [and] swell into a mechanised pagan chorus'.l They become both literally and symbolically the intrusive machines in the Edenic garden of Ausrralian radicalism, which Ashbolt maintains 'went up a cul-de-sac in the first decade of this century'. The growth and shaping of suburbia, rhen, becomes indicative of the hardening 'pattern of conformity', while the Victa-that symbol of 'personal property . demo- cratic rights . [and] power'-has subdued rhe pre-war ideal of 1 B¡nsrs or Su¡un¡n (orsrnucltc I llmr lto Srlc¡ rn rx¡ Glnor¡ Su¡un¡ 'Australian radicalism, mixed as itwas with the inchoate spirit of connected to a program of reform which is sophisticated nationalism'.2 but fundamentally conservative of capitalist social relations.5 For Allan Ashbolt, the developmenr of suburbia after'$íorld ,logic, IØar Il.represented the loss of something identifiably Austral- A key factor here is rhe element of which .rrrd"ríi'e, "rry ian-th'e healthy radicalism linked to the left-wing nationalism of metonymic and metaphoric relation between word and subject. -

Annual Report 2018-2019

2018-2019 ANNUAL REPORT Digital copy of this report is available online on Council’s website at www.bayside.nsw.gov.au/your-council/corporate-planning-and-reporting Content IntroDuctION StatutorY StateMentS 4 Mayor’s Message 79 Local Government Act 1993 5 General Manager’s Message 83 Local Government (General) Regulation 2005 6 About Bayside 102 Companion Animals Act 1998 8 About Council 103 Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 105 Government Information (Public Access) Act 2009 ProGress ReportING 110 Privacy and Personal Information Protection Act 12 Major Projects Update 111 Public Interest Disclosures Act 1994 22 Capital Expenditure for 2018-2019 112 Capital Expenditure Guidelines 2010 26 Community Strategic Plan Themes 112 Fisheries Management Act 1994 31 2018-2019 Action Reporting 113 Swimming Pools Act 1992 114 Carer (Recognition) Act 2010 115 Disability Inclusion Act 2014 120 Transport Corridor Outdoor Advertising and Signage Guidelines (2017) – RMS FINANCIAL StateMentS 122 Financial Report Mayor’s Message As the newly elected Mayor I am proud to present Bayside Council’s Annual Report 2018/19 outlining our activities and expenditures. I am proud to be part of a team of Councillors and staff who work hard to deliver quality services and facilities for our community. This Annual Report is a testament to our commitment to the successful renewal of Bayside. The report provides a snapshot of our projects, achievements services and initiatives. It also provides accountability on the strategic matters and gives Council an opportunity to reflect on future challenges. I have attended many events and had the opportunity to meet with many residents. -

The Making of White Australia

The making of White Australia: Ruling class agendas, 1876-1888 Philip Gavin Griffiths A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University December 2006 I declare that the material contained in this thesis is entirely my own work, except where due and accurate acknowledgement of another source has been made. Philip Gavin Griffiths Page v Contents Acknowledgements ix Abbreviations xiii Abstract xv Chapter 1 Introduction 1 A review of the literature 4 A ruling class policy? 27 Methodology 35 Summary of thesis argument 41 Organisation of the thesis 47 A note on words and comparisons 50 Chapter 2 Class analysis and colonial Australia 53 Marxism and class analysis 54 An Australian ruling class? 61 Challenges to Marxism 76 A Marxist theory of racism 87 Chapter 3 Chinese people as a strategic threat 97 Gold as a lever for colonisation 105 The Queensland anti-Chinese laws of 1876-77 110 The ‘dangers’ of a relatively unsettled colonial settler state 126 The Queensland ruling class galvanised behind restrictive legislation 131 Conclusion 135 Page vi Chapter 4 The spectre of slavery, or, who will do ‘our’ work in the tropics? 137 The political economy of anti-slavery 142 Indentured labour: The new slavery? 149 The controversy over Pacific Islander ‘slavery’ 152 A racially-divided working class: The real spectre of slavery 166 Chinese people as carriers of slavery 171 The ruling class dilemma: Who will do ‘our’ work in the tropics? 176 A divided continent? Parkes proposes to unite the south 183 Conclusion -

South Eastern Sydney Local Priorities

Targeted Earlier Intervention Program Sydney, South Eastern Sydney and Northern Sydney South Eastern Sydney District Local Priorities We will take a local approach We know that every local community is different and has distinct needs and priorities. Local knowledge is crucial to identifying and addressing these needs. That’s why we’re taking a local approach to recommissioning for Targeted Earlier Intervention (TEI). The new TEI program will focus on collecting data so you can learn more about your local community. This will help you to identify needs, as they change, in your area. As the evidence grows, you’ll be able to adapt your service to what works in your community. This is crucial to supporting children, young people, families and communities experiencing, or at risk of experiencing, vulnerability in NSW. Department of Communities and Justice (DCJ) Districts will work with you to identify the needs and priorities of your community. We will look at: local priority groups – who needs the services most in your community? location – where in your local area are the services needed most? service type – what kinds of services will work in your area? This evidence-based snapshot outlines the main priority groups in your District. This will help you to plan services that can make a real difference in your local area. Local Priorities for South Eastern Sydney District In no particular order 1. Children, young people and families or carers affected by mental ill-health, substance misuse, separation, or domestic and family violence 2. Children, young people and families with multiple risk factors 3. -

Paolo Giorza and Music at Sydney's 1879 International Exhibition

‘Pleasure of a High Order:’ Paolo Giorza and Music at Sydney’s 1879 International Exhibition Roslyn Maguire As Sydney’s mighty Exhibition building took shape, looking to the harbour from an elevated site above the Botanic Gardens, anxiety and excitement mounted. This was to be the first International Exhibition held outside Europe or America and musical entertainment was to be its greatest attraction.1 An average of three thousand people would attend each week day and as recent studies have shown, Sydney’s International Exhibition helped initiate reforms to education, town planning, technologies, photography, manufacturing and patronage of the arts, music and literature.2 Although under construction since January 1879, it was mid May before the Exhibition’s influential Executive Commissioner Patrick Jennings3 announced the appointment of his friend, Milanese composer Paolo Giorza4 as musical director: [H]is credentials are of such a nature both as a conductor, composer and artist, that I could not justly pass them over. I think that he should also be authorised to compose a march and cantata for the opening ceremony … Signor Giorza offers to give his exclusive services as composer and director and performer on the organ and to organise a competent orchestra of local artists for promenade concerts, and to conduct the same.5 The extent of Jennings’s personal interest in Exhibition music is evident in this report publicising Giorza’s appointment. It amounts to one of the colony’s most interesting cultural documents for the ideas, attitudes and objectives it reveals, including consideration of whether an ‘Australian School of Music, as distinguished from any of the well-defined schools’ existed. -

Votes and Proceedings

129 129 1913. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. No. 48. VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. FRIDAY, 31ST OCTOBER, 1913. 1. The H[ou, mielt, at half-past ten o'clock a.m., puirsunt to adjourniiniit.Mr. Speaker took the Chair, .and read Prayers. 2. MESSAGES FROM THE GOVERNOR-GENERAL.-ASSENT TO BILLS.-The following Messages from His Excellency the Governor-General were presented, and the same were read by IMr.Speaker :- (Supply Bill (No. 4) 1913-14)-- DENMAN, Governor-General. Message No. 17. A Bill intituled " An Act to grant and apply a sum out of the Consolidated Revenue Fund for the service of the year ending the thirtieth day of June One thousand nine hundred and fourteen," as finally passed by the Senate and the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth, having been presented to the -Governor-General for the Royal Assent, His Excellency has, in the name and on behalf of His Majesty, assented to the said Act. Government House, Melbourne, 30th October, 1913. (Excise Tarif'[Sugar] Bill)- DENMAN, Governor-General. Message No. 18. A Bill intituled " An Act to impose a Duty of Excise upon certain Sugar," as finally passed by the Senate and the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth, having been presented to the Governor-General for the Royal Assent, His Excellency has, in the name and on behalf of His Majesty, assented to the said Act. Government House, Melbourne, 30th October, 1913. (Sugar Bounty Bill)- DENMAN, Governor-General. Message No. 19. A Bill intituled "An Act to provide for a Bounty to Growers of Sugar Cane and Beet," as finally passed by the Senate and the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth, having been presented to the Governor-General for the Royal Assent, His Excellency has, in the name and on behalf of His Majesty, assented to the said Act. -

Bruce Smith and Anglo-Australian Liberalism

The Historical Journal (2021), 1–21 doi:10.1017/S0018246X21000522 ARTICLE Bruce Smith and Anglo-Australian Liberalism Alastair Paynter School of Humanities (History), University of Southampton, Southampton, UK Email: [email protected] Abstract Bruce Smith (1851–1937) was the most prominent Australian exponent of classical or ‘old’ liberalism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Although his polit- ical career was not particularly successful, he was notable as the foremost defender of individualism as the authentic liberal creed, exemplified by his 1887 work Liberty and liberalism. He consistently attacked new liberalism, with its acceptance of extensive state interference, and socialism, as inimical to individual liberty and national prosper- ity. Although he is now recognized as an important figure in the Australian liberal pan- theon, there has been relatively little attention to his thought outside Australia itself, despite his extensive connections to Britain. The general trajectory of Australian liber- alism from ‘individualism’ to ‘collectivism’ was mirrored in Britain from the 1880s, especially during Prime Minister William Gladstone’s second and third administrations, when the radicals within the Liberal party grew in influence and the aristocratic whig moderates waned. Smith maintained close links with the British Liberty and Property Defence League, which dedicated itself to fighting against collectivism, as well as with his personal hero, the philosopher Herbert Spencer, from whom his own politics derived much influence. This article considers Smith’s thought through the prism of Anglo-Australian politics. As a political culture, Australia did not make much impression on British minds until relatively late in the nineteenth century. -

Papers of Sir Edmund Barton Ms51

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA PAPERS OF SIR EDMUND BARTON MS51 Manuscript Collection 1968-70, 1996 and last amended 2001 PAPERS OF EDMUND BARTON MS51 TABLE OF CONTENTS Overview 3 Biographical Note 6 Related Material 8 Microfilms 9 Series Description 10 Series 1: Correspondence 1827-1921 10 Series 2: Diaries, 1869, 1902-03 39 Series 3: Personal documents 1828-1939, 1844 39 Series 4: Commissions, patents 1891-1903 40 Series 5: Speeches, articles 1898-1901 40 Series 6: Papers relating to the Federation Campaign 1890-1901 41 Series 7: Other political papers 1892-1911 43 Series 8: Notes, extracts 1835-1903 44 Series 9: Newspaper cuttings 1894-1917 45 Series 10: Programs, menus, pamphlets 1883-1910 45 Series 11: High Court of Australia 1903-1905 46 Series 12: Photographs (now in Pictorial Section) 46 Series 13: Objects 47 Name Index of Correspondence 48 Box List 61 2 PAPERS OF EDMUND BARTON MS51 Overview This is a Guide to the Papers of Sir Edmund Barton held in the Manuscript Collection of the National Library of Australia. As well as using this guide to browse the content of the collection, you will also find links to online copies of collection items. Scope and Content The collection consists of correspondence, personal papers, press cuttings, photographs and papers relating to the Federation campaign and the first Parliament of the Commonwealth. Correspondence 1827-1896 relates mainly to the business and family affairs of William Barton, and to Edmund's early legal and political work. Correspondence 1898-1905 concerns the Federation campaign, the London conference 1900 and Barton's Prime Ministership, 1901-1903. -

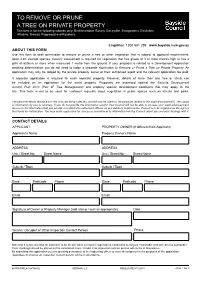

To Remove Or Prune a Tree on Private

TO REMOVE OR PRUNE A TREE ON PRIVATE PROPERTY This form is for the following suburbs only: Banksmeadow, Botany, Daceyville, Eastgardens, Eastlakes, Hillsdale, Mascot, Pagewood and Rosebery. Enquiries: 1300 581 299 www.bayside.nsw.gov.au ABOUT THIS FORM Use this form to seek permission to remove or prune a tree or other vegetation that is subject to approval requirements. Apart from exempt species, Council assessment is required for vegetation that has grown to 3 or more metres high or has a girth of 600mm or more when measured 1 metre from the ground. If your proposal is related to a Development Application awaiting determination you do not need to lodge a separate Application to Remove or Prune a Tree on Private Property. An application may only be lodged by the private property owner or their authorised agent and the relevant application fee paid. A separate application is required for each separate property. However, details of more than one tree or shrub can be included on an application for the same property. Proposals are assessed against the Bayside Development Control Plan 2013 (Part 3F Tree Management) and property specific development conditions that may apply to the site. This form is not to be used for customer requests about vegetation in public spaces such as streets and parks. The personal details requested on this form are being collected, and will only be used for, the purposes related to this application/payment. The supply of information by you is voluntary. If you do not provide the information sought, then Council will not be able to process your application/payment. -

3 Dunstan Woolner

Thomas Woolner’s “Bad Times for Sculpture”: Framing Victorian Sculpture in Vocabularies of Neglect Angela Dunstan In 1890, one of the Victorian era’s most successful sculptors, Thomas Woolner, bemoaned what he perceived to be the declining cultural value of his profession, writing that “people do not care for sculpture very much” (Letter to Henry Parkes 8 December 1890). Perhaps little has changed.1 As Jason Edwards recently observed, “In spite of the sustained re-investigation of Victorian culture in recent decades nineteenth century British sculpture continues to be neglected” (201). This article will revisit this history of neglect, considering the second half of the nineteenth century as a key era for sculpture; a time of fluctuating cultural, aesthetic and economic value for the art. Drawing on the case study of Pre-Raphaelite sculptor, Thomas Woolner, I will show how he pragmatically cast and recast his profession as both high art and a popular art form in order to defend the dignity and technical complexity of sculpture whilst maintaining a living by it. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, capitalising on cultural developments as varied as British imperialism, growing opportunities for travel and the phenomenon of celebrity became increasingly imperative to a sculptor’s success. By necessity, Woolner’s generation of sculptors had to modify their methods to remain competitive in a mass market rapidly crowded by replicas, statuettes and the ephemera which were invading everyday life and becoming characteristic of modernity. Woolner’s rhetorical moulding of sculpture as an art appealing both to the elite and to the popular markets makes a useful case study in the plasticity of Victorian sculptors themselves as they responded to the changes in the aesthetic and economic value of their art, adapting their methods and adopting new approaches in ways which would reframe the cultural value of the profession by the end of the nineteenth century.