The 1914 Double Dissolution Election and Its Legacy. Helen Irving It Is Not

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1835. EXECUTIVE. *L POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT

1835. EXECUTIVE. *l POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT. Persons employed in the General Post Office, with the annual compensation of each. Where Compen Names. Offices. Born. sation. Dol. cts. Amos Kendall..., Postmaster General.... Mass. 6000 00 Charles K. Gardner Ass't P. M. Gen. 1st Div. N. Jersey250 0 00 SelahR. Hobbie.. Ass't P. M. Gen. 2d Div. N. York. 2500 00 P. S. Loughborough Chief Clerk Kentucky 1700 00 Robert Johnson. ., Accountant, 3d Division Penn 1400 00 CLERKS. Thomas B. Dyer... Principal Book Keeper Maryland 1400 00 Joseph W. Hand... Solicitor Conn 1400 00 John Suter Principal Pay Clerk. Maryland 1400 00 John McLeod Register's Office Scotland. 1200 00 William G. Eliot.. .Chie f Examiner Mass 1200 00 Michael T. Simpson Sup't Dead Letter OfficePen n 1200 00 David Saunders Chief Register Virginia.. 1200 00 Arthur Nelson Principal Clerk, N. Div.Marylan d 1200 00 Richard Dement Second Book Keeper.. do.. 1200 00 Josiah F.Caldwell.. Register's Office N. Jersey 1200 00 George L. Douglass Principal Clerk, S. Div.Kentucky -1200 00 Nicholas Tastet Bank Accountant Spain. 1200 00 Thomas Arbuckle.. Register's Office Ireland 1100 00 Samuel Fitzhugh.., do Maryland 1000 00 Wm. C,Lipscomb. do : for) Virginia. 1000 00 Thos. B. Addison. f Record Clerk con-> Maryland 1000 00 < routes and v....) Matthias Ross f. tracts, N. Div, N. Jersey1000 00 David Koones Dead Letter Office Maryland 1000 00 Presley Simpson... Examiner's Office Virginia- 1000 00 Grafton D. Hanson. Solicitor's Office.. Maryland 1000 00 Walter D. Addison. Recorder, Div. of Acc'ts do.. -

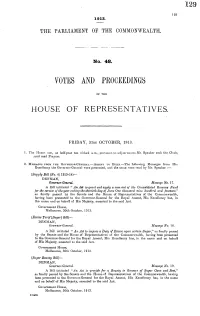

Votes and Proceedings

129 129 1913. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. No. 48. VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. FRIDAY, 31ST OCTOBER, 1913. 1. The H[ou, mielt, at half-past ten o'clock a.m., puirsunt to adjourniiniit.Mr. Speaker took the Chair, .and read Prayers. 2. MESSAGES FROM THE GOVERNOR-GENERAL.-ASSENT TO BILLS.-The following Messages from His Excellency the Governor-General were presented, and the same were read by IMr.Speaker :- (Supply Bill (No. 4) 1913-14)-- DENMAN, Governor-General. Message No. 17. A Bill intituled " An Act to grant and apply a sum out of the Consolidated Revenue Fund for the service of the year ending the thirtieth day of June One thousand nine hundred and fourteen," as finally passed by the Senate and the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth, having been presented to the -Governor-General for the Royal Assent, His Excellency has, in the name and on behalf of His Majesty, assented to the said Act. Government House, Melbourne, 30th October, 1913. (Excise Tarif'[Sugar] Bill)- DENMAN, Governor-General. Message No. 18. A Bill intituled " An Act to impose a Duty of Excise upon certain Sugar," as finally passed by the Senate and the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth, having been presented to the Governor-General for the Royal Assent, His Excellency has, in the name and on behalf of His Majesty, assented to the said Act. Government House, Melbourne, 30th October, 1913. (Sugar Bounty Bill)- DENMAN, Governor-General. Message No. 19. A Bill intituled "An Act to provide for a Bounty to Growers of Sugar Cane and Beet," as finally passed by the Senate and the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth, having been presented to the Governor-General for the Royal Assent, His Excellency has, in the name and on behalf of His Majesty, assented to the said Act. -

Voting in AUSTRALIAAUSTRALIA Contents

Voting IN AUSTRALIAAUSTRALIA Contents Your vote, your voice 1 Government in Australia: a brief history 2 The federal Parliament 5 Three levels of government in Australia 8 Federal elections 9 Electorates 10 Getting ready to vote 12 Election day 13 Completing a ballot paper 14 Election results 16 Changing the Australian Constitution 20 Active citizenship 22 Your vote, your voice In Australia, citizens have the right and responsibility to choose their representatives in the federal Parliament by voting at elections. The representatives elected to federal Parliament make decisions that affect many aspects of Australian life including tax, marriage, the environment, trade and immigration. This publication explains how Australia’s electoral system works. It will help you understand Australia’s system of government, and the important role you play in it. This information is provided by the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC), an independent statutory authority. The AEC provides Australians with an independent electoral service and educational resources to assist citizens to understand and participate in the electoral process. 1 Government in Australia: a brief history For tens of thousands of years, the heart of governance for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples was in their culture. While traditional systems of laws, customs, rules and codes of conduct have changed over time, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples continue to share many common cultural values and traditions to organise themselves and connect with each other. Despite their great diversity, all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities value connection to ‘Country’. This includes spirituality, ceremony, art and dance, family connections, kin relationships, mutual responsibility, sharing resources, respecting law and the authority of elders, and, in particular, the role of Traditional Owners in making decisions. -

Table of Contents Chronology of Events

Table of Contents Chronology of Events .............................................................................................................................................................. 4 History- 1788 to 1900 .............................................................................................................................................. 5 Plenary ‘sovereign’ Parliaments ........................................................................................................................................ 5 History- Towards Federation- 1880 to 1990 ................................................................................................... 6 Federation (1901)...................................................................................................................................................... 7 Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 (Imp) ...................................................................................... 7 Post Federation- 1901 to 1986 (Parliamentary Sovereignty) ................................................................... 8 ‘Balfour Declaration 1926’ [1.3.9E] .................................................................................................................................. 8 Statute of Westminster 1931 (UK) [1.3.11E] ................................................................................................................ 8 The Australia Acts .................................................................................................................................................................. -

Australia's System of Government

61 Australia’s system of government Australia is a federation, a constitutional monarchy and a parliamentary democracy. This means that Australia: Has a Queen, who resides in the United Kingdom and is represented in Australia by a Governor-General. Is governed by a ministry headed by the Prime Minister. Has a two-chamber Commonwealth Parliament to make laws. A government, led by the Prime Minister, which must have a majority of seats in the House of Representatives. Has eight State and Territory Parliaments. This model of government is often referred to as the Westminster System, because it derives from the United Kingdom parliament at Westminster. A Federation of States Australia is a federation of six states, each of which was until 1901 a separate British colony. The states – New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and Tasmania - each have their own governments, which in most respects are very similar to those of the federal government. Each state has a Governor, with a Premier as head of government. Each state also has a two-chambered Parliament, except Queensland which has had only one chamber since 1921. There are also two self-governing territories: the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory. The federal government has no power to override the decisions of state governments except in accordance with the federal Constitution, but it can and does exercise that power over territories. A Constitutional Monarchy Australia is an independent nation, but it shares a monarchy with the United Kingdom and many other countries, including Canada and New Zealand. The Queen is the head of the Commonwealth of Australia, but with her powers delegated to the Governor-General by the Constitution. -

Bicameralism

Bicameralism International IDEA Constitution-Building Primer 2 Bicameralism International IDEA Constitution-Building Primer 2 Elliot Bulmer © 2017 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) Second edition First published in 2014 by International IDEA International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. The electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribute-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information on this licence visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/> International IDEA Strömsborg SE–103 34 Stockholm Sweden Telephone: +46 8 698 37 00 Email: [email protected] Website: <http://www.idea.int> Cover design: International IDEA Cover illustration: © 123RF, <http://www.123rf.com> Produced using Booktype: <https://booktype.pro> ISBN: 978-91-7671-107-1 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 3 Advantages of bicameralism..................................................................................... -

The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918 Volume Xi Australia During the War

THE OFFICIAL HISTORY OF AUSTRALIA IN THE WAR OF 1914-1918 VOLUME XI AUSTRALIA DURING THE WAR AUSTRALIA DURING THE WAR BY ERNEST SCOTT Pmfcsor of Histow in the Vniwuty of Mdhe With 67 illustrations Sezientli Edition AUSTRALIA ANGUS AND ROBERTSON LTD. 09 CASTLEREACH STREET, SYDNEY 1941 Printed and Bcund in Australia by Halstead Press Pty Limited, 9-19 Nickson Street. Sydney. Registered at the General Post Office, Melbourne, for trana- mission through the post as a book. Obtainable in Great Britain at Australia House and from all booksellers (sole agent for wholesale distribution-The Official Secretary for the Commonwealth of Australia, Australia House, Strand, London, W C.2); in Canada from the Australian Trade Commissioner, 15 King Street West, Toronto: in the United States from the Australian Government Trade Commissioner, International Building, 630 Fifth Avenue, New York; and in New Zealand from the Australian Trade Commissioner, D.1 C. Building, Wellington. First Edtliott . , . 1936 Srroitd Edition . , 1937 Third Editioii . , . 1938 Foiirth Edition . 1939 Fifth Edition . 1939 Sixth Edition . 1940 Sewnth Edition . 1941 PREFACE THISbook is a member of a series recording the participation of the Commonwealth of Australia in the Great European War, but it differs from its companion volumes in scope and subject-matter. They are concerned with battles-in Egypt, Gallipoli, France, and Palestine; with the activities of the young Australian navy; with medical services; with the occupation of territory formerly under German government. Substantially the greater part of those works relates to what was done by Australian soldiers, sailors, medical officers, and administrators outside their own country, though on duties vitally affecting Australia and the Empire to which she belongs. -

Origins of the Royal Commission on Intelligence and Security

Origins of the Royal Commission on Intelligence and Security CJ Coventry LLB BA A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Research) School of Humanities and Social Sciences UNSW Canberra at ADFA 2018 i Table of Contents Acknowledgements iii Introduction & Methodology 1 Part I: ASIO before Whitlam 9 Chapter One: The creation of ASIO 9 Chapter Two: Bipartisan anti-communism 23 Chapter Three: ASIO’s anti-radicalism, 1950-1972 44 Part II: Perspectives on the Royal Commission 73 Chapter Four: Scholarly perspectives on the Royal Commission 73 Chapter Five: Contemporary perspectives on ASIO and an inquiry 90 Part III: The decision to reform 118 Chapter Six: Labor and terrorism 118 Chapter Seven: The decision and announcement 154 Part IV: The Royal Commission 170 Chapter Eight: Findings and recommendations 170 Conclusion 188 Bibliography 193 ii Acknowledgements & Dedication I dedicate this thesis to Rebecca and our burgeoning menagerie. Most prominently of all I wish to thank Rebecca Coventry who has been integral to the writing of this thesis. Together we seek knowledge, not assumption, challenge, not complacency. For their help in entering academia I thank Yunari Heinz, Anne-Marie Elijah, Paul Babie, the ANU Careers advisors, Clinton Fernandes and Nick Xenophon. While writing this thesis I received help from a number of people. I acknowledge the help of Lindy Edwards, Toni Erskine, Clinton Fernandes, Ned Dobos, Ruhul Sarkar, Laura Poole-Warren, Kylie Madden, Julia Lines, Craig Stockings, Deane-Peter -

Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Sixteen

Chapter Three The Answer to the Prime Minister’s Section 57 Dilemma Ray Evans1 I begin this paper with a quotation from Sir John Downer, who at the Adelaide Convention on March 29, 1897, when discussing the intractable issue of responsible government on the one hand, and the existence of a Senate with the power to deny supply to the Executive on the other, said this: “We only know responsible government through the evolution of centuries; but in this instance we will have evolved it not in centuries but in days. The result of this will be a good understanding between the two Houses, great mutual respect, and peace and happiness”. There hasn’t been much mutual respect, peace and happiness between the House of Representatives and the Senate in recent years. Paul Keating, who really didn’t have much to complain about as far as the Senate was concerned, famously described Senators as “unrepresentative swill”.2 In his statement of 25 February, 2004, entitled Australia’s Demographic Challenges, the current Treasurer, Peter Costello, discussed desired labour market reforms in the context of jobs for older people. He said: “A number of further workplace relations reforms are currently proposed: reform of unfair dismissal laws to minimise the impact on employment, particularly for small business; simplification of procedures for agreement-making; improvements to the remedies and sanctions against unprotected action; improvements to bargaining processes; and improvements to the processes for union right of entry to the workplace. These reforms have been blocked in the Senate”. Amendments to the Workplace Relations Act are one of the Bills which have been twice refused passage by the Senate. -

BOOK I-AUSTRALIA at WAR CHAPTER 1 If

BOOK I-AUSTRALIA AT WAR CHAPTER 1 THE OUTBREAK OF WAR ON the 30th of June, 1914, the Australian daily newspapers contained cablegrams announcing the startling fact that two days previously the heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian empire, the Archduke Frariz Ferdinand, together with the Archduchess, had been assassiiinted at Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia, by a Serbian political desperado. The news was, of course, published under large headlines in the journals. Obviously an important event in world politics had occurred. Some serious consequences might be expected to follow. But nobody in Australia dreamt that this crime committed in the Balkans was of momentous concern for this country. If anyone had suggested that nearly 60,000 men in the prime of life and physical capacity were marked for death, and that 140,000 more would suffer maiming, as a consequence of what had happened at Sarajevo, his prediction would have seemed too absurd for credence. Where was Sarajevo? It is likely that many Australians had never even heard of the place, though memories of a school geography lesson, or study of the map of Europe, may have brought the name to the minds of a few. Shakespeare did not know where Bohemia was: in a stage direction at the head of Act 3, Scene 3, of The IVinter’s Tale, he referred to it as “Bohemia, a desert country near the sea,” though it is an inland country with no seaboard whatever. Where Shakespeare tripped we shall intend no reproach if we assume that Australians were not very well informed about a remote town in a small Balkan state. -

Biography Joseph Cook (1860-1947) Member for Parramatta (New South

James Newton Haxton Hume Cook (1866-1942) Joseph Cook (1860-1947) Member for Bourke (Victoria) 1901-1910 Member for Parramatta (New South Wales) 1901-1921 orn in Kihikihi, New Zealand, After leaving Parliament, Cook assisted orn in Silverdale, Staffordshire, England, Representatives. He was solid in his BJames Hume Cook arrived in Australia in W.M. Hughes with political activities and held BJoseph Cook migrated to the Lithgow opposition to the Protectionist Government 1881. An estate agent, Cook became involved various high-ranking positions in industrial district of New South Wales in 1885 to work behind his leader, George Reid, and grew in politics through an association with the organisations. He was made a fellow of the in the coalmines. A Methodist lay preacher increasingly estranged from the Labor Party. Australian Natives Association (ANA), and Royal Economic Society in 1936 for his for much of his adult life, he believed it his In 1908 he became Leader of the Freetrade represented East Bourke in the Victorian services to Protectionist causes on the duty to improve conditions for the working Party and in 1909 became Deputy Leader Legislative Assembly 1894-1900. He was recommendation of J.M. Keynes. Cook class from which he originated. He became and Minister for Defence in the Deakin Fusion Mayor of Brunswick, Victoria, in 1896. He was was appointed CMG in 1941. involved in union and labour movement Government. When Deakin resigned as an advocate of federation and urged the ANA activities, serving on the Labor Defence Prime Minister in 1913, Cook became leader to support the Constitution Bill produced by Committee in Lithgow during the maritime of the Liberal Party and subsequently the Australasian Federal Convention of 1897. -

Australian Elections Timetable As at 1 September 2016

RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2016–17 1 SEPTEMBER 2016 ‘So when is the next election?’: Australian elections timetable as at 1 September 2016 Rob Lundie Politics and Public Administration Section Contents Introduction ................................................................................................ 2 The Commonwealth .................................................................................... 2 The rules ............................................................................................................. 2 House of Representatives election ..................................................................... 3 Half-Senate election ........................................................................................... 3 Simultaneous half-Senate and House of Representatives election ................... 3 Double dissolution election ................................................................................ 4 Next Commonwealth election ............................................................................ 4 States and territories ................................................................................... 6 Northern Territory ............................................................................................ 6 Australian Capital Territory .............................................................................. 6 Western Australia ............................................................................................. 6 South Australia ................................................................................................