A Crumbling Fortress Is Our God

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nederlandse Dagbladen En De Roma

Nederlandse dagbladen en de Roma Een onderzoek naar objectiviteit en beeldvorming Afstudeerscriptie Grytsje Anna Pietersma Journalistiek Christelijke Hogeschool Ede 2009 – 2010 Begeleider Hans Pfauth 2 Hoofdstukindeling Voorwoord Pag. 5 Hoofdstuk 1 De Roma Pag. 7 1.1 Een zwervend volk 1.2 Herkomst 1.4 Gebonden in de slavernij 1.5 Metaalbewerkers en muzikanten 1.6 Europese (on)gastvrijheid 1.7 Roma in Nederland 1.8 De Verzwelging – Porraimos Hoofdstuk 2 Anno nu Pag. 15 2.1 Feiten 2.2 Zigeuners in Nederland 2.3 Oost-Europa 2.4 Europese Unie 2.5 Christelijke betrokkenheid Hoofdstuk 3 Beeldvorming in de media Pag. 20 3.1 Wat is objectiviteit? 3.1.1. Bronnen 3.1.2. Hoofdrolspelers 3.1.3. Feiten 3.1.4. Selectie 3.2 Hoe werkt beeldvorming in de media? 3.2.1. Beeldvorming 3.2.2. Stereotiepe beeldvorming 3.3 Onderzoek in Nederlandse media Hoofdstuk 4 Onderzoek kwantitatieve berichtgeving Pag. 26 4.1 Onderzochte media 4.2 Tijdsperiode 4.3 Onderzoek 4.3.1 Selectie 4.3.2 Schema 4.4 De resultaten 4.4.1 Lengte berichtgeving 4.4.2 Bron 4.4.3 Plaats in de krant 3 4.4.4 Genre 4.4.5 Onderwerp Hoofdstuk 5 Onderzoek kwalitatieve berichtgeving Pag. 33 5.1 Methode 5.2 Gebeurtenissen 5.3 Thematiek 5.4 Lokale semantiek 5.5.1 Werkwijze 5.5 Stijl en retoriek 5.6 Relevantiestructuren Hoofdstuk 6 Interviews Pag. 54 met schrijfster Mariët Meester met chef buitenland van het Nederlands Dagblad Gerhard Wilts Hoofdstuk 7 Conclusies en aanbevelingen Pag. 60 7.1 Conclusies hoeveelheid aandacht 7.2 Conclusies praktijkonderzoek deel 1 7.3 Conclusies inhoud berichtgeving 7.4 Conclusies praktijkonderzoek deel 2 7.3 Aanbevelingen Literatuurlijst Pag. -

Beyond Pluralism?

RESEARCH MASTER POLITICAL SCIENCE AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION, LEIDEN UNIVERSITY Religious Pluralism A study on the declining protection of religion in the Netherlands Marthe A. Harkema S1153560 Leiden, 15 August, 2013 Master thesis Department of Political Science Leiden University Supervisor: Dr. F. de Zwart Second reader: Dr. F. Ragazzi Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Research topic ................................................................................................................................. 3 Research Approach .......................................................................................................................... 8 1. Religious pluralism in the Netherlands ............................................................................................. 10 The historical and institutional background of religious pluralism ............................................... 10 Principled pluralism ....................................................................................................................... 12 The protection of religion by the court and in parliament ........................................................... 15 The court’s protection of religion .................................................................................................. 16 Parliament’s protection of religion .............................................................................................. -

Minder Nieuws Voor Hetzelfde Geld? Van Broadsheet Naar Tabloid

www.nieuwsmonitor.net Minder nieuws voor hetzelfde geld? Van broadsheet naar tabloid Onderzoekers Nieuwsmonitor Carina Jacobi Meer weten? Meer Joep Schaper Kasper Welbers Kim Janssen Maurits Denekamp Nel Ruigrok 06 27 588 586 [email protected] www.nieuwsmonitor.net Twitter: @Nieuwsmonitor Inleiding Vanaf half april 2013 is alleen De Telegraaf nog op broadsheet te lezen. De laatste jaren hebben de landelijke dagbladen één voor één een ander formaat gekregen. Veelal ging dit gepaard met discussie. Zo zou het tabloid-formaat leiden tot minder en vooral kortere artikelen. In dit rapport gaan we na in hoeverre deze verwachting juist is gebleken. Van de landelijke dagbladen onderzoeken we of en in welke mate het aantal artikelen, de lengte van de artikelen, de lengte van de woorden en de lengte van de koppen is veranderd sinds de dagbladen op tabloid zijn overgegaan. Van broadsheet naar tabloid Het begrip tabloid verwijst niet alleen naar het formaat van de krant. In de andere betekenis ligt een kwalitatief oordeel over de journalistiek ten grondslag. De term is afkomstig uit Engeland waar ‘de tabloids’ overmatig veel aandacht besteden aan sensatieverhalen, roddel, sterren, seks, sport en andere human interest verhalen. Voor een toenemend aantal human interest artikelen in kwaliteitskranten is in de wetenschap de term ‘tabloidization’ bedacht. In Nederland hebben we de bekende roddelbladen, maar kennen we niet de tabloidkranten zoals in Engeland, die het tabloidformaat koppelen aan een berichtgeving zoals in de roddelpers. De overgang op het tabloidformaat door Trouw, AD, de Volkskrant en NRC Handelsblad was geen inhoudelijke keuze, maar was puur gebaseerd op het handzamer formaat. -

Concentratie En Pluriformiteit Van De Nederlandse Media 2006

mediaconcentratie in beeld concentratie en pluriformiteit van de nederlandse media 2006 © september 2007 Commissariaat voor de Media 01-03_colofon/inhoud.indd 1 12-09-2007 09:46:28 Colofon Het rapport Mediaconcentratie in Beeld is een uitgave van het Commissariaat voor de Media. Redactie Quint Kik Edmund Lauf Rini Negenborn Vormgeving FC Klap MediagraphiX Druk Roto Smeets GrafiServices Commissariaat voor de Media Hoge Naarderweg 78 lllll 1217 AH Hilversum Postbus 1426 lllll 1200 BK Hilversum T 035 773 77 00 lllll F 035 773 77 99 lllll [email protected] lllll www.cvdm.nl lllll www.mediamonitor.nl ISSN 1874-0111 01-03_colofon/inhoud.indd 2 12-09-2007 09:46:28 inhoud Voorwoord 4 Samenvatting 5 1. Trends 15 2. Mediabedrijven 21 2.1 Uitgevers en omroepen 22 2.2 Kabel- en telecomexploitanten 31 3. Mediamarkten 37 3.1 Dagbladen 37 3.2 Opiniebladen 42 3.3 Televisie 43 3.4 Radio 48 3.5 Internet 52 3.6 Reclame 56 4. Historische ontwikkeling dagbladenmarkt 61 4.1 Uitgevers 61 4.2 Titels 66 4.3 Kernkranten 69 5. Lokale dagbladedities in Nederland 77 5.1 Situatie 1987 en 2006 77 5.2 Lokale berichtgeving 1987 en 2006 79 5.3 Exclusiviteit van dagbladedities 83 5.4 Meer redactionele synergie, minder pluriformiteit 84 6. De gratis revolutie 87 Annex 99 A. Begrippen 99 B. Methodische verantwoording 103 C. Overige tabellen 113 Literatuur 122 01-03_colofon/inhoud.indd 3 12-09-2007 09:46:29 voorwoord Enkele maanden geleden trad een lang bepleite nieuwe wettelijke regeling voor media cross- ownership in werking. -

Monitor Ontwikkeling Mediagebruik 2018

Monitor Ontwikkeling Mediagebruik Rapport editie 2018 Dieter Verhue Bart Koenen Januari 2018 H4515 Inhoudsopgave 1. Doel en opzet onderzoek p. 3 2. Samenvatting p. 6 3. Politiek en overheidsbeleid: mediatrends p. 9 4. Impactscores p. 12 5. Via welke media kijkt, luistert en leest men? p. 27 6. Praten en het gebruik sociale media p. 42 7. Onderzoeksverantwoording p. 51 2 Hoofdstuk 1 Doel en opzet Achtergrond De Monitor Ontwikkeling Mediagebruik (MOM) geeft inzicht in het mediagebruik van het Nederlands publiek als het gaat om informatie over politiek en overheidsbeleid. De centrale vraag van het onderzoek is: Welke mediatitels hebben in Nederland onder het algemeen publiek en bij specifieke groepen de meeste impact als het gaat om informatie over politiek en overheidsbeleid? De Monitor Ontwikkeling Mediagebruik werd voor het eerst uitgevoerd in 2010. In 2012 en 2015 zijn een tweede en derde meting uitgevoerd. Omdat het medialandschap sterk aan verandering onderhevig is, is de vragenlijst dit jaar (2018) aangepast en meer ‘toekomstbestendig’ gemaakt. Door deze aanpassing is in veel gevallen een directe vergelijking met de eerdere onderzoeken niet meer te maken. De resultaten zijn gebaseerd op een online onderzoek onder een representatieve steekproef van 1.996 personen van 15 jaar en ouder, dat in de periode van 7 tot en met 16 december 2017 is uitgevoerd. In dit onderzoek is het mediagebruik in kaart gebracht door voor alle relevante titels (radio, televisie, online, dagbladen, tijdschriften, sociale media) het bereik en het belang in kaart te brengen. Op basis van een combinatie van deze criteria is de impact van de titels bepaald. -

CEDAW, the Bible and the State of the Netherlands: the Struggle Over Orthodox Women’S Political Participation and Their Responses Oomen, B.M.; Guijt, J.; Ploeg, M

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) CEDAW, the Bible and the State of the Netherlands: the struggle over orthodox women’s political participation and their responses Oomen, B.M.; Guijt, J.; Ploeg, M. Published in: Utrecht Law Review DOI: 10.18352/ulr.129 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Oomen, B. M., Guijt, J., & Ploeg, M. (2010). CEDAW, the Bible and the State of the Netherlands: the struggle over orthodox women’s political participation and their responses. Utrecht Law Review, 6(2), 158-174. DOI: 10.18352/ulr.129 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: http://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (http://dare.uva.nl) Download date: 18 Jan 2019 CEDAW, the Bible and the State of the Netherlands: the struggle over orthodox women’s political participation and their responses Barbara M. -

Energy Justice and Smart Grid Systems Evidence from The

Applied Energy 229 (2018) 1244–1259 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Applied Energy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/apenergy Energy Justice and Smart Grid Systems: Evidence from the Netherlands and the United Kingdom T ⁎ Christine Milchrama, , Rafaela Hillerbrandb,a, Geerten van de Kaaa, Neelke Doorna, Rolf Künnekea a Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management, Delft University of Technology, Jaffalaan 5, 2628 BX Delft, The Netherlands b Institute for Technology Assessment and Systems Analysis, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, P.O. Box 3640, 76021 Karlsruhe, Germany HIGHLIGHTS • This paper broadens current conceptualizations of energy justice for smart grids. • The study explores values in the public debates on smart grids in two countries. • Value conflicts show the importance of distributive and procedural justice. • It is debated if the systems lead to more equity or reinforce injustices. • Energy justice needs to be broadened to include data privacy and security issues. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Smart grid systems are considered as key enablers in the transition to more sustainable energy systems. However, Smart grid systems debates reflect concerns that they affect social and moral values such as privacy and justice. The energy justice Energy justice framework has been proposed as a lens to evaluate social and moral aspects of changes in energy systems. This Sustainability paper seeks to investigate this proposition for smart grid systems by exploring the public debates in the Values Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Findings show that smart grids have the potential to effectively address Public debate justice issues, for example by facilitating small-scale electricity generation and transparent and reliable billing. -

2 March 2005 COURT of the HA

IN THE NAME OF THE QUEEN rvp\I + II Case number: 192880 Cause list number: 03-57 Date of judgement: 2 March 2005 COURT OF THE HAGUE Civil Law Sector & Full Court Judgement in the case under the case number and cause list number mentioned above of: 1. the foundation De Nederlandse Dagbladpers, domiciled in Amsterdam, 2. the private company with limited liability Koninklijke BDU Uitgeverij B.V., domiciled in Barneveld, 3. the private company with limited liability Het Financieele Dagblad B.V., domiciled in Amsterdam, 4. the private company with limited liability Friesch Dagblad Holding B.V., domiciled in Leeuwarden, 5. the private company with limited liability Nedag Beheer B.V., domiciled in Barneveld, 6. the private company with limited liability Nederlandse Dagblad B.V., domiciled in Barneveld, 7. the private company with limited liability NCD Holding B.V., domiciled in Groningen, 8. the private company with limited liability Friese Pers B.V., domiciled in Leeuwarden, 9. the private company with limited liability Hazewinkel Pers B.V., domiciled in Groningen, 10. the limited liability company PCM Uitgevers N.V., domiciled in Amsterdam, 11. the private company with limited liability PCM Landelijke Dagbladen B.V., domiciled in Amsterdam, 12. the private company with limited liability Algemeen Dagblad B.V., domiciled in Rotterdam, 13. the private company with limited liability NRC Handelsblad B.V., domiciled in Rotterdam, 14. the private company with limited liability Trouw B.V., domiciled in Amsterdam, 15. the private company with limited liability De Volkskrant B.V., domiciled in Amsterdam, 16. the private company with limited liability Het Parool B.V., domiciled in Amsterdam, 17. -

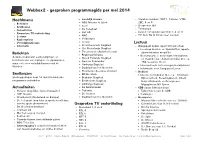

Gesproken Programmagids Webbox2

Webbox2 - gesproken programmagids per mei 2014 Hoofdmenu Landelijk nieuws Vlaamse zenders: VRT1, Canvas, VTM, NOS Nieuws & Sport 2BE, 4 en 5 Berichten nu.nl Gesproken tijd Snelkeuzes De Telegraaf Testkanaal Actualiteiten Het AD Luister TV (geluid van Ned.1, 2 en 3) Gesproken TV-ondertiteling NRC TV Gids Nu & Straks (per zender) Lectuur Radiostations Volkskrant Verenigingsnieuws Trouw Lectuur Informatie Reformatorisch Dagblad Aangepast Lezen (apart lidmaatschap) Het Nederlands Dagblad Leesmap kranten en tijdschriften (aparte Berichten Tweakers (technisch nieuws) abonnementen mogelijk) Regionaal nieuws Boekenplank (+toevoegen/verwijderen Actuele (regionale) aankondigingen en Noord Hollands Dagblad berichten van verenigingen en organisaties, uit maandelijkse Aanwinstenlijst met ca. Gooi en Eemlander 150 nieuwste titels) maar ook over ontwikkelingen rond de Limburgs Dagblad Webbox Hoorspelhoek (+toevoegen/verwijderen) Dagblad van het Noorden Informatie over Aangepast Lezen Provinciale Zeeuwse Courant Dedicon Snelkeuzes BN De Stem Diverse periodieken met o.a. Informatie Snelkoppelingen naar 10 laatst beluisterde Brabants Dagblad Rijksoverheid, Belastingdienst, Albert programma-onderdelen Eindhovens Dagblad Heijn Allerhande en Greenpeace Limburgs Dagblad Magazine en NS Spoor. Actualiteiten De Gelderlander CBB (apart lidmaatschap) Horizon (dagelijkse luistermagazine) Tubantia Tijdschriften van de CBB ANP nieuws De Stentor Catalogus Weerbericht (Nederland en Europa) Dagblad van het Noorden Hoorspelen De Telegraaf (dagelijks gesproken volledige Maandelijkse selectie van ca. 10 titels versie; apart abonnement) Gesproken TV ondertiteling Commissaris Van In (10 series) De Slechtziendenkrant Nederland 1,2 en 3 Bonita Avenue Journaal 24 RTL 4 Sprong in het heelal Met het oog op morgen RTL 5 Pekelvlees Politiek 24 NET 5 De Spin Tweede Kamer (verschillende zalen) SBS 6 De Moker NOS Teletekst RTL 7 AVRO Radiotheater Internetpagina's actuele nieuwsberichten RTL 8 Het Bureau, van J.J. -

Christenen Nigeria Vluchten

nederlands dagblad christelijk betrokken 9° 4 jaargang 68 nr. 17.886 www.nd.nl [email protected] 0342 411711 dinsdag 27 december 2011 nd prijs € 1,50 zaterdag € 2,50 geloof Nederland Leert wil niet de zoveelste missionaire truc lanceren pagina 2 buitenland Terugblik vanuit 5 continenten. Vandaag voorbeeldig Estland pagina 4 reportage Tsjetsjeense moeders, ‘zwartkonten’ leven voor hun kinderen pagina 8 voetbalclub FairPlay op 20 opinie Er is niets mis met verhuisplicht voor werklozen pagina 11 * redactie buitenland nd.nl/buitenland beeld epa Christenen Nigeria vluchten Ruurd Ubels nd.nl/economie Geen boef, toch een dikke boete … Via hoge boetes voor werkgevers wil de overheid illegale arbeid uitbannen. Ondernemers zoals bouwers, tuinders en krantenuitgevers hebben al voor miljoenen euro’s opgelegd gekregen. … Maar is elke beboete werkgever wel zo’n schurk? ‘Zó heeft de wetgever het nooit bedoeld.’ ▶Amsterdam Vrijdag 10 juni 2010. Vader Rob en zoon Danny Verheijen van Driehoek Meubels laten de ramen van hun Am- sterdamse bedrijf wassen. Al elf jaar ge- beurt dat door een Zaans glazenwasser- bedrijf. Plotseling staat er iemand van de Arbeidsinspectie voor Danny’s neus, die hem vraagt even mee naar buiten te lopen, waar de inspecteur hem wijst op een soppende Bulgaar zonder werkver- gunning. Enkele maanden later valt bij Driehoek Meubels een boete op de deurmat: 8000 euro. Het schoonmaakbedrijf krijgt bovendien eenzelfde boete voor het in dienst hebben van de illegale werknemer. De rooms-katholieke St. Theresa Kerk in Madalla, nabij de Nigeriaanse hoofdstad Abjuja, werd op eerste kerstdag verwoest Rob Verheijen is met stomheid gesla- door een bomaanslag. -

Pdf Document

Zuilen in de Polder? Een verkenning van de institutionalisering van de islam in Nederland Ewoud Butter Roemer van Oordt Colofon Auteurs: Ewoud Butter & Roemer van Oordt Coverontwerp: Hamid Oujaha ISBN: 9789402178852 Opdrachtgever: Ministerie van Sociale Zaken en Werkgelegenheid. Het ministerie van SZW heeft als auteursrechthebbende toestemming gegeven het rapport te laten publiceren. September 2017 Alle rechten voorbehouden. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand en/of openbaar gemaakt in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch, door fotokopieën, opnamen of op enige andere manier zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de auteurs. Inhoudsopgave 1. Inleiding 11 2. Moslims in Nederland: aantallen en stromingen 19 2.1. Korte geschiedenis van moslims in Nederland 19 2.2. Aantal moslims 21 2.3. Etnische diversiteit 24 2.4. Religieuze diversiteit; islamitische stromingen 26 3. Organisatievorming in historisch en maatschappelijk perspectief 33 3.1. Inleiding 34 3.2. Moskee en staat in Nederland 35 3.3. Het Nederlandse islamdebat. De periode voor 1989 41 3.4. Fatwa van Khomeini tegen Salman Rushdie (1989) 44 3.5. Eerste Golfoorlog (1990) 48 3.6. Botsende beschavingen 50 3.7. De wereld na 11 september 2001 58 3.8. Twee politieke moorden en de opkomst van Hirsi Ali 64 3.9. Preventie van radicalisering 73 3.10. De Deense cartoon-affaire 76 3.11. Ex-moslims en seculiere moslims 79 3.12. Geert Wilders, de PVV en Fitna 89 3.13. Geert Wilders (2): proces, gedoogpartner en cartoons 96 3.14. Verbod op ritueel slachten 102 3.15. Anders Behring Breivik en de Eurabië theorie 104 3.16. -

FRAMING RIO 2016 an Analysis of Media Coverage and Framing of Rio As Host of the Olympics 2016 in Belgian and Dutch Newspapers

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lirias FRAMING RIO 2016 An analysis of media coverage and framing of Rio as host of the Olympics 2016 in Belgian and Dutch newspapers Sarah Van den Broucke Project management: Tine Van Regenmortel FRAMING RIO 2016 An analysis of media coverage and framing of Rio as host of the Olympics 2016 in Belgian and Dutch newspapers Sarah Van den Broucke Project management: Tine Van Regenmortel Research commissioned by FWO – Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek Gepubliceerd door KU Leuven HIVA ONDERZOEKSINSTITUUT VOOR ARBEID EN SAMENLEVING Parkstraat 47 bus 5300, 3000 LEUVEN, België [email protected] www.hiva.be D/2017/4718/003 – ISBN 9789055506200 © typ het jaartal HIVA KU Leuven Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvuldigd en/of openbaar gemaakt door middel van druk, fotokopie, microfilm of op welke andere wijze ook, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by mimeograph, film or any other means, without permission in writing from the publisher. Contents List of tables 5 List of figures 7 Introduction 9 1 | Methodology 11 1.1 Data Sources 11 1.2 Data collection 12 1.3 Coverage analysis 12 1.4 Framing analysis 13 2 | Coverage analysis 16 2.1 Research Questions 1 16 2.2 Topics covered 16 2.3 Comparison of coverage by country and source (quality vs. popular press) 21 2.4 Tone of coverage 23 2.5 Evolution through time 25 3 | Framing analysis 29 3.1 Research Questions 2 29 3.2 Use of frames in Rio 2016 coverage 29 3.3 Comparison of frames by country and source (quality vs.