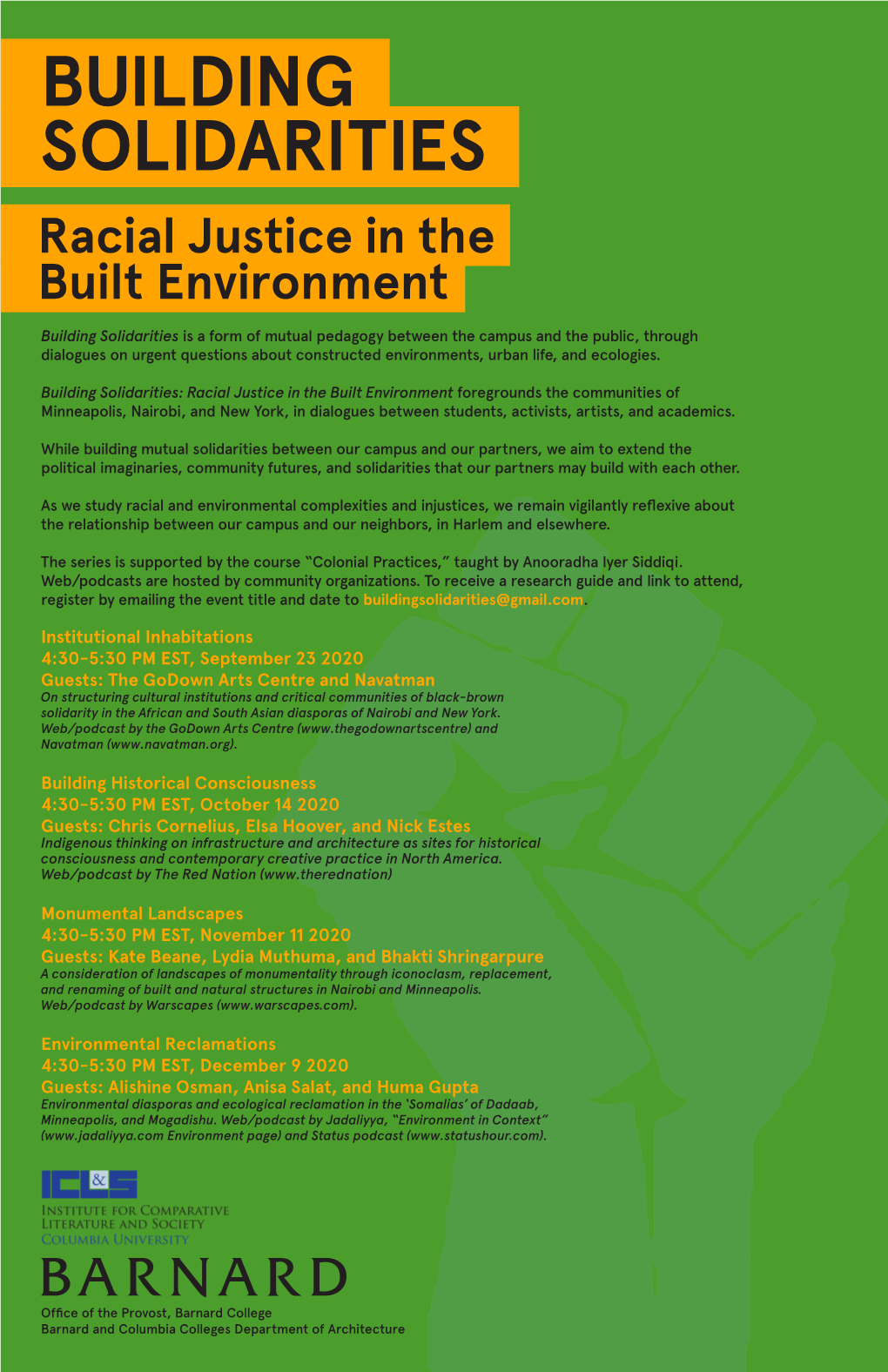

BUILDING SOLIDARITIES Racial Justice in the Built Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecovillaggi: Esperienze Comunitarie Tra Utopia E Realtà

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Archive - Università di Pisa UNIVERSITÀ DI PISA DIPARTIMENTO DI SCIENZE POLITICHE E SOCIALI CORSO DI DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN STORIA E SOCIOLOGIA DELLA MODERNITÀ Ecovillaggi: esperienze comunitarie tra utopia e realtà CANDIDATA Rossana Guidi TUTOR Prof. Mario Aldo Toscano Ciclo 2007-2009 1 L’utopia del futuro costruisce il presente. (Prigogine) 2 Indice: Introduzione…………………………………………………… p. 5. Parte I: Industrializzazione, capitalismo, modernità………...p. 12. 1.1 Nascita della società capitalistica moderna………………...p. 13. Parte II: Le avventure intellettuali e pratiche della comunità. ……………………………………………………………………p. 26. 2.2.1 Dissoluzione e resistenze della comunità………………... p. 26. 2.2.2 Tracce di comunità……………………………………..... p. 36. 2.2.3 Dalla comunità alla società: il pensiero degli autori classici della sociologia…………………………………..p. 41. Parte III: Il pensiero utopico e le sue realizzazioni……………p. 57 3.1 Socialisti utopisti……………………………………………..p. 57. 3.2 Comunitarismo americano…………………………………...p. 69. 3.3 Movimento Hippy……………………………………………p. 82. 3.4 Sviluppo sostenibile e nascita degli ecovillaggi…………….p. 86. Parte IV: Fenomenologia e geopolitica dell’ecovillaggio……p. 100. 4.1 Definizione di ecovillaggio…………………………… p. 100. 4.2 Ecovillaggi a confronto………………………………... p. 110. 4.2.1 Il metodo decisionale…………………………………...p. 113. 4.3.2 Organizzazione economica……………………………..p. 124. 4.3.3 Accorgimenti ecologici………………………………..p. 130. 3 4.3.4 Orientamento religioso………………………………...p. 138. 4.4 Ecovillaggi: tra utopia e realtà………………………....p. 140. 4.5 Contenuto razionalistico degli ecovillaggi…………….p. 151. 4.6 Breve quadro concettuale sulla disuguaglianza sociale..p. 168. Parte V: Punto applicativo e descrizione di un caso specifico: la comune di Bagnaia……………………………………….……p. -

ALEX DELGADO Production Designer

ALEX DELGADO Production Designer PROJECTS DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS THE KEYS OF CHRISTMAS David Meyers YouTube Red Feature OPENING NIGHTS Isaac Rentz Dark Factory Entertainment Feature Los Angeles Film Festival G.U.Y. Lady Gaga Rocket In My Pocket / Riveting Short Film Entertainment MR. HAPPY Colin Tilley Vice Short Film COMMERCIALS & MUSIC VIDEOS SOL Republic Headphones, Kraken Rum, Fox Sports, Wendy’s, Corona, Xbox, Optimum, Comcast, Delta Airlines, Samsung, Hasbro, SONOS, Reebok, Veria Living, Dropbox, Walmart, Adidas, Go Daddy, Microsoft, Sony, Boomchickapop Popcorn, Macy’s Taco Bell, TGI Friday’s, Puma, ESPN, JCPenney, Infiniti, Nicki Minaj’s Pink Friday Perfume, ARI by Ariana Grande; Nicki Minaj - “The Boys ft. Cassie”, Lil’ Wayne - “Love Me ft. Drake & Future”, BOB “Out of My Mind ft. Nicki Minaj”, Fergie - “M.I.L.F.$”, Mike Posner - “I Took A Pill in Ibiza”, DJ Snake ft. Bipolar Sunshine - “Middle”, Mark Ronson - “Uptown Funk”, Kelly Clarkson - “People Like Us”, Flo Rida - “Sweet Spot ft. Jennifer Lopez”, Chris Brown - “Fine China”, Kelly Rowland - “Kisses Down Low”, Mika - “Popular”, 3OH!3 - “Back to Life”, Margaret - “Thank You Very Much”, The Lonely Island - “YOLO ft. Adam Levine & Kendrick Lamar”, David Guetta “Just One Last Time”, Nicki Minaj - “I Am Your Leader”, David Guetta - “I Can Only Imagine ft. Chris Brown & Lil’ Wayne”, Flying Lotus - “Tiny Tortures”, Nicki Minaj - “Freedom”, Labrinth - “Last Time”, Chris Brown - “She Ain’t You”, Chris Brown - “Next To You ft. Justin Bieber”, French Montana - “Shot Caller ft. Diddy and Rick Ross”, Aura Dione - “Friends ft. Rock Mafia”, Common - “Blue Sky”, Game - “Red Nation ft. Lil’ Wayne”, Tyga “Faded ft. -

Tv Shows, Feature Films & Documentaries

TV SHOWS, FEATURE FILMS & DOCUMENTARIES TITLES AVAILABLE DUBBED AND SUBTITLED IN SPANISH. INDEX INDEX TITLES AVAILABLE DUBBED ...And It’s Snowing Outside! 6 Grand Torino (The) 27 Storm (The) 14 Angel Of Sarajevo (The) 6 Hidden Vatican (The) 7 Terra Sancta: Guardians Of Salvation’s Source 25 Assault (The) 10 Imperium: Nero 19 Third Secret Of Fatima (The) 27 Bartali, The Iron Man 16 Imperium: Pompeii 19 Third Truth (The) 28 Borsellino, The 57 Days 12 Imperium: Saint Augustine 20 Turin’s Butterfly 11 Boss In The Kitchen (A) 9 Imperium: Saint Peter 20 Wannabe Widowed 12 Bright Flight 13 Lady Of The Camellias 21 Caravaggio 16 Long Lasting Youth 21 Claire & Francis 17 Maria Goretti 28 Countess Of Castiglione (The) 25 Marriage (A) 8 Curfew - Don Pappagallo (The) 26 Mearshes Intrique (The) 22 Displaced Child (The) 11 My House Is Full Of Mirrors 15 Don Zeno 17 Oro Di Scampia (L’) 7 Fear Of Loving 1, 2 9 Over The Shop 13 Francesco 22 Pompeii, Stories From An Eruption 23 Frederick Barbarossa 15 Resurrection 23 Giovanni Falcone, The Judge 18 Saint Bakhita 24 Girls Of San Frediano (The) 26 Scent Of Love 14 Giuseppe Moscati, 18 Song’e Napule 10 Good Season (A) 8 Star Of Bethlehem 24 Credits not contractual Credits INDEX TITLES AVAILABLE SUBTITLED Anija 36 Lonely Hero (A) 42 Away From Me 33 Smile Of The Leader (The) 35 Balancing Act (The) 37 Song’e Napule 34 Black Souls 31 Triplet (The) 39 Caesar Must Die 36 Viva La Libertà 35 Cardboard Village (The) 40 Chair Of Happiness (The) 34 Darker Than Midnight 31 Dinner (The) 32 Easy 40 Entrepreneur (The) 41 -

Introduction: Indigenous Peoples and the Politics of Water

Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society Vol 7., No 1, 2018, pp. 1-18 Introduction: Indigenous peoples and the politics of water Melanie K. Yazzie University of New Mexico Cutcha Risling Baldy Humboldt State University Abstract In recent history, we have seen water assume a distinct and prominent role in Indigenous political formations. Indigenous peoples around the world are increasingly forced to formulate innovative and powerful responses to the contamination, exploitation, and theft of water, even as our efforts are silenced or dismissed by genocidal schemes reproduced through legal, corporate, state, and academic means. The articles in this issue offer multiple perspectives on these pressing issues. They contend that struggles over water figure centrally in concerns about self-determination, sovereignty, nationhood, autonomy, resistance, survival, and futurity. Together, they offer us a language to challenge and resist the violence enacted through and against water, as well as a way to envision and build alternative futures where water is protected and liberated from enclosures imposed by settler colonialism, capitalism, and heteropatriarchy. Keywords: water, decolonization, Indigenous feminism, relationality ã M. Yazzie & C. Baldy. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0), permitting all non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium provided the original work is properly cited. Yazzie & Baldy 1 Introduction The now popular discourse “Water Is Life” has become almost ubiquitous across multiple decolonization struggles in North America and the Pacific over the past five years. Its rise in popularity reflects how Indigenous people are (re)activating water as an agent of decolonization, as well as the very terrain of struggle over which the meaning and configuration of power is determined (Yazzie, 2017). -

Chicana/Os Disarticulating Euromestizaje By

(Dis)Claiming Mestizofilia: Chicana/os Disarticulating Euromestizaje By Agustín Palacios A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Laura E. Pérez, Chair Professor José Rabasa Professor Nelson Maldonado-Torres Universtiy of California, Berkeley Spring 2012 Copyright by Agustín Palacios, 2012 All Rights Reserved. Abstract (Dis)Claiming Mestizofilia: Chicana/os Disarticulating Euromestizaje by Agustín Palacios Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Laura E. Pérez, Chair This dissertation investigates the development and contradictions of the discourse of mestizaje in its key Mexican ideologues and its revision by Mexican American or Chicana/o intellectuals. Great attention is given to tracing Mexico’s dominant conceptions of racial mixing, from Spanish colonization to Mexico’s post-Revolutionary period. Although mestizaje continues to be a constant point of reference in U.S. Latino/a discourse, not enough attention has been given to how this ideology has been complicit with white supremacy and the exclusion of indigenous people. Mestizofilia, the dominant mestizaje ideology formulated by white and mestizo elites after Mexico’s independence, proposed that racial mixing could be used as a way to “whiten” and homogenize the Mexican population, two characteristics deemed necessary for the creation of a strong national identity conducive to national progress. Mexican intellectuals like Vicente Riva Palacio, Andrés Molina Enríquez, José Vasconcelos and Manuel Gamio proposed the remaking of the Mexican population through state sponsored European immigration, racial mixing for indigenous people, and the implementation of public education as a way to assimilate the population into European culture. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

The War with the Sioux: Norwegians Against Indians 1862-1863 Translation of Karl Jakob Skarstein Krigen Mot Siouxene: Nordmenn Mot Indianerne 1862-1863

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Digital Press Books The Digital Press at the University of North Dakota 2015 The aW r with the Sioux Karl Jakob Skarstein Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/press-books Recommended Citation Skarstein, Karl Jakob, "The aW r with the Sioux" (2015). Digital Press Books. 3. https://commons.und.edu/press-books/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The Digital Press at the University of North Dakota at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Press Books by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE WAR WITH THE SIOUX: NORWEGIANS AGAINST INDIANS 1862-1863 Translation of Karl Jakob Skarstein Krigen mot siouxene: nordmenn mot indianerne 1862-1863. Copyright © 2015 by The Digital Press at The University of North Dakota Norwegian edition published by Spartacus Forlag AS, Oslo © Spartacus Forlag AS 2008 Published by Agreement with Hagen Agency, Oslo “Translators’ Preface” by Danielle Mead Skjelver; “Historical Introduction” by Richard Rothaus, “Becoming American: A Brief Historiography of Norwegian and Native Interactions” by Melissa Gjellstad, and “The Apple Creek Fight and Killdeer Mountain Conflict Remembered” by Dakota Goodhouse, are available with a CC-By 4.0 license. The translation of this work was funded with generous support from a NORLA: Norwegian Literature Abroad grant. www.norla.no The book is set in Janson Font by Linotype except for Dakota Goodhouse’s contribution which is set in Times New Roman. -

Nome DE VREESE LUC PIETER Indirizzo 210/1, VIA DON ZENO

F ORMATO EUROPEO PER IL CURRICULUM VITAE INFORMAZIONI PERSONALI Nome DE VREESE LUC PIETER Indirizzo 210/1, VIA DON ZENO SALTINI, 41123 MODENA, ITALIA Telefono +39 3396447373 E-mail [email protected]; [email protected] Nazionalità Belga (con residenza anagrafica e fiscale in Italia) Data di nascita 23/02/1958 ESPERIENZA LAVORATIVA • Date (da – a) DA MARZO 2016 (ANCORA IN CORSO) • Nome e indirizzo del datore di Fondazione Luigi Boni Onlus, Viale Luigi Cadorna, 4 46029 Suzzara (MN lavoro • Tipo di azienda o settore Terzo Settore: Servizi (semi)residenziali e domiciliari socio-sanitari • Tipo di impiego Medico Libero professionista (fino al 30/09/2016) - Dirigente Medico (CCNL Dirigenti Sanità Pubblica Area IV a tempo indeterminato e a tempo parziale 30 ore settimanali) • Principali mansioni e responsabilità − Medico Referente RSA 2 (p.l. 80) e del Centro Diurno Integrato (20 posti) della Fondazione Luigi Boni Onlus (fino al 31/05/2018) − Direttore Sanitario della Fondazione Luigi Boni Onlus che ha le seguenti U.d.O.: RSA1 (85 p.l.); RSA2 (p.l. 80); CDI (20 posti); ADI; RSA aperta e Poliambulatorio (dal 1/06/2018) Referente COVID (da Aprile 2020) − − Visite psicogeriatriche ambulatoriali o domiciliari in libera professione • Date (da – a) DAL 1/03/2018 AL 31/12/2020 • Nome e indirizzo del datore di Cooperativa Sociale Villa Maria (Disabilità Intellettiva Adulta e Anziana), Via Castelbeseno, 8 lavoro 38060 Calliano (TN) • Tipo di azienda o settore Terzo Settore: Residenze Socio-Sanitarie • Tipo di impiego Direttore Sanitario con contratto libero professionale (fino al 06/01/2020) – Direttore Sanitario a tempo determinato “acausale” – categoria “Q” (Quadri) per una prestazione media complessiva di 8 ore settimanali • Principali mansioni e responsabilità Direttore Sanitario delle 2 residenze socio-sanitarie (Villa Maria a Calliano 42 p.l. -

Michele Ranchetti

Archivio Michele Ranchetti Biografia Marco Pacioni Elenco analitico dei documenti Rita Romanelli Archivio Michele Ranchetti Biografia Marco Pacioni Elenco analitico dei documenti Rita Romanelli SOMMARIO Biografia di Michele Ranchetti (M. Pacioni)1* pag. 7 Bibliografia (M. Pacioni) pag. 15 L’archivio di Michele Ranchetti (R. Romanelli) pag. 21 Elenco analitico dei documenti (R. Romanelli) pag. 23 Corrispondenza pag. 23 Poesie pag. 24 Appunti manoscritti pag. 25 Testi dattiloscritti e a stampa pag. 28 Dattiloscritti su storia e cristianesimo pag. 28 Dattiloscritti su autori e testi pag. 29 Dattiloscritti su Freud e psicanalisi pag. 30 Saggi e articoli di Michele Ranchetti pag. 31 Saggi su Michele Ranchetti e interviste pag. 31 Testi di e su Ranchetti degli ultimi anni pag. 33 Temi di studio pag. 35 Diodati pag. 35 Padri della chiesa pag. 36 Antico e nuovo testamento pag. 37 Storia della Chiesa - Papi, concilii pag. 37 Pascal pag. 38 Catechismi – Schelling – S. Paolo pag. 39 Lutero pag. 41 Modernismo pag. 43 Pensiero religioso – ebraismo pag. 43 Storia della chiesa – Università pag. 45 Legislazione ecclesiastica pag. 45 Filosofia, logica e teologia – autori A-Z pag. 45 Benjamin e Scholem pag. 50 Taubes e Schmidt pag. 51 Heidegger pag. 51 Bultmann e Barth pag. 52 Bonhoeffer pag. 52 Fonti di filosofia e logica pag. 52 Wittgenstein pag. 53 Freud e psicoanalisi pag. 56 Dattiloscritti su Freud pag. 57 Freud e Fliess pag. 58 Freud e Ranck pag. 58 Psicologia e psicoanalisi pag. 58 Copie di saggi editi su Freud pag. 59 1 * La biografia è la versione più estesa della voce Michele Ranchetti scritta da Marco Pacioni per il Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani – Treccani. -

And the Stress Begins... the More, the Minier in a Galaxy Far, Far

The Lambert Post Volume IV, Issue III Lambert High School December 2012 Hannah Quire Staff Writer And The Stress Begins... The weather is getting colder, and winter break is just around the corner, but before we can all celebrate the two and a half weeks of school-less bliss, we must all suffer through one thing: midterms. Contrary to popular belief, however, there is a way to sift through the stress, tears, and chaos of midterms and live to tell the tale. I. Take advantage of study times. There are multiple study periods allotted throughout the week, during the classes that do not have any exams that day. By utilizing those block periods to study, it can ease the stress of cramming until the early hours the night before. “When you see that you have your sixth period exam after IF, don’t stress about that one the night before,” Mr. Wason, the AP department head, recommends. He adds, “Use the schedule to your advantage.” II. Be specific with questions. Ask your teachers what the test will be like. Will it be a cumulative test, or just over one unit? How many questions are there? What style of questions will be asked? By knowing what’s coming, you can better prepare for the tests, rather than going into them blindly. III. Don’t wait until the week before. “Most teachers will make the midterm cumulative,” Mr. Wason says. “You need to be preparing early for your more difficult classes” because of the amount of information that the exam will cover, he advises. -

Wednesday, February 15, 2017 Bridgewater-Raynham Regional

Wednesday, February 15, 2017 Bridgewater-Raynham Regional School Committee Meeting Bridgewater-Raynham Regional High School 415 Center Street Bridgewater, Massachusetts Lecture Hall Regular Meeting 7:00 P.M. Agenda 7:00 P.M. I. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE II. APPROVAL OF MINUTES— January 25, 2017 III. CORRESPONDENCE/RECOGNITION A. Nancy Kirk, WIS Principal B. TJ2 C. BRRHS Track Coaches IV. PUBLIC COMMENT V. EDUCATIONAL REPORTS A. Student Advisory Council Report B. Wellness Advisory Report-Mrs. Fahey VI. ADMINISTRATIVE AND SCHOOL COMMITTEE REPORTS A. MSBA Update-Mr. Swenson B. Special Education Parent Advisory Council Report-Mrs. Scleparis C. Budget Subcommittee Update- Dr. Prewandowski D. Policy Subcommittee Report-Mr. Dolan E. Personnel Update- Ms. Gormley VII. UNFINISHED BUSINESS VIII. NEW BUSINESS A. Course Selection Booklet-Ms. Watson B. Proposal of 2017-2018 School Calendar(First Reading)-Mr. Powers C. School Choice for 2017-2018 School Year-Ms. Macedo D. Request to Incur Debt for the Purpose of the MASC Feasibility Study-Mr. Connolly E. Acceptance of Gifts- Mr. Swenson *Ocean State Job Lot Books to GMES * Gift Card Donation to Raynwater Players-$500.00 *$1,200. BSU Grant to Fund BMS MCAS Boost Program IX. ADJOURNMENT January 25, 2017 Bridgewater-Raynham Regional School Committee Open Session Minutes c.30A, § 22) Date: January 25, 2017 Time: 7:30 PM Location: Library of Raynham Middle School located at 420 Titicut Road, Raynham, MA. The Meeting was called to order by Chairperson Riley at 7:30 PM The following Committee Members were present: Mr. Michael Dolan, Member Mrs. Lorraine Levy, Member Mr. L. Anthony Ghelfi, Member Mrs. -

Don Zeno Saltini

DON ZENO SALTINI Fossoli, 30 agosto 1900 - Grosseto, 15 gennaio 1981 è stato il presbitero italiano, fondatore della comunità Nomadelfia. a cura di Lucio Bregoli Circolo Acli - Vittorio Loda - Villaggio Prealpino 1900 - LA FAMIGLIA DI DON ZENO 30 agosto 1900. A Fossoli di Carpi (MO), in una benestante famiglia patriarcale, da Cesare Saltini e Filomena Righi nasce Zeno. È il nono di dodici figli. La famiglia di don Zeno Saltini nel 1916. Zeno è il primo seduto a sinistra Tra questi Marianna, conosciuta come Mamma Nina (1889-1957), farà nascere a Carpi la Casa della Divina Provvidenza che si occupa di ragazze in stato di abbandono. Marianna Saltini con in braccio una piccola abbandonata Il fratello don Vincenzo (1896-1961) darà vita all’Istituto degli Oblati, per formare sacerdoti in grado di divenire educatori nei seminari; Anita entrerà nel monastero delle Clarisse di Carpi con il nome di suor Scolastica. Don Vincenzo Saltini Monastero delle Clarisse di Carpi 1914 - IL RIFIUTO DELLA SCUOLA A 14 anni e mezzo Zeno rifiuta di andare a scuola, strappando il permesso al padre con l’intervento del parroco, don Sisto Campagnoli, che sempre lo comprenderà e lo aiuterà. Sostiene che a scuola inse- gnano cose che non incidono sulla vita. 1912. Zeno in mezzo alla sua classe in 5ª elementare (al centro) Il padre lo manda a lavorare nei poderi della famiglia, vive in mezzo ai braccianti e ne condivide le giuste aspirazioni. Ha così modo di entrare a contatto con la dura realtà dei braccianti da cui imparò le teorie socialiste. Zeno al lavoro nei campi Una delle numerose cooperative agricole dell’Emilia Romagna Mezzo di trasporto preferito dal giovane Zeno 1920 - LA DISCUSSIONE CON L’ANARCHICO A 17 anni è chiamato sotto le armi, durante la prima guerra mondiale, e presta servizio militare fino al marzo del 1919.