Geography in Spain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spaniards & Their Country

' (. ' illit,;; !•' 1,1;, , !mii;t( ';•'';• TIE SPANIARDS THEIR COUNTRY. BY RICHARD FORD, AUTHOR OF THE HANDBOOK OF SPAIN. NEW EDITION, COMPLETE IN ONE VOLUME. NEW YORK: GEORGE P. PUTNAM, 155 BROADWAY. 1848. f^iii •X) -+- % HONOURABLE MRS. FORD, These pages, which she has been, so good as to peruse and approve of, are dedicated, in the hopes that other fair readers may follow her example, By her very affectionate Husband and Servant, Richard Ford. CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. PAOK. A General View of Spain—Isolation—King of the Spains—Castilian Precedence—Localism—Want of Union—Admiration of Spain—M. Thiers in Spain , . 1 CHAPTER II. The Geography of Spain—Zones—Mountains—The Pyrenees—The Gabacho, and French Politics . ... 7 CHAPTER in. The Rivers of Spain—Bridges—Navigation—The Ebro and Tagus . 23 CHAPTER IV. Divisions into Provinces—Ancient Demarcations—Modern Depart- ments—Population—Revenue—Spanish Stocks .... 30 CHAPTER V. Travelling in Spain—Steamers—Roads, Roman, Monastic, and Royal —Modern Railway—English Speculations 40 CHAPTER VI. Post Office in Spain—Travelling with Post Horses—Riding post—Mails and Diligences, Galeras, Coches de DoUeras, Drivers and Manner of Driving, and Oaths 53 CHAPTER VII. SpanishHorsea—Mules—Asses—Muleteers—Maragatos ... 69 — CONTENTS. CHAPTER VIII. PAGB. Riding Tour in Spain—Pleasures of it—Pedestrian Tour—Choice of Companions—Rules for a Riding Tour—Season of year—Day's • journey—Management of Horse ; his Feet ; Shoes General Hints 80 CHAPTER IX. The Rider's cos.tume—Alforjas : their contents—The Bota, and How to use it—Pig Skins and Borracha—Spanish Money—Onzas and smaller coins 94 CHAPTER X. -

United States International University – Africa

UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY – AFRICA COURSE SYLLABUS SPN 4000: CULTURE AND CIVILIZATION OF SPAIN PREREQUISITE: SPN 2500 CREDIT: 3 UNITS LECTURER: OFFICE HOURS: Co requisite: SPN 2500; Post requisite: SPN 3001, 5 page term paper; presentations to faculty and students. COURSE DESCRIPTION This course is a survey of the geography, history, dance, architecture, art, fine arts, science, culture and customs of Spain. The course is conducted in Spanish and includes a three week educational tour of Spain. All students are interviewed prior to acceptance into Windows to the World Program. COURSE OBJECTIVES ♦ To build up the confidence in the use of Spanish as communication by providing opportunities to share ideas on Spain, its culture and civilization. ♦ To provide a general idea and appreciation of Spain: The richness of its peoples, civilization and history. ♦ To provide a framework for Windows to the World - Spain Program. COURSE CONTENT (a) The geography of Spain 1. Extension, climate, population 2. Mountain ranges and principal rivers 3. Minerals and principal products 4. Territorial division of country 5. Extraterritorial possessions 6. Principal cities (b) The history of Spain 1. Primitive times 2. The Moors and the Reconquist 3. The greatness of Spain 4. Decadence 5. Eighteenth-twentieth century (c) The fine Arts and Science 1. Music 2. Composers, instrumentalists and singers 3. Dance 4. Arquitecture 5. Painting - El Greco, Ribera, Zurburán, Velásquez, Murillo, Goya, Sorolla, Zuluaga, Sert, Picasso, Miró, Dalí 6. Men of science - Ramón y Cajal, Juan de la Cierva, Severo Ochoa (d) The life and customs of Spain today 1. The house and family 2. -

Welcome Living in Spain

Welcome to Torrejon Welcome Living in Spain GEOGRAPHY OF SPAIN The Kingdom of Spain is located on the Iberian Peninsula in south-western Europe, with archipelagos in the Atlantic Ocean (Canary Islands) and Mediterranean Sea (Balearic Islands), and several small territories on and near the north African coast, Ceuta and Melilla, in continental North Africa. COMMUNITY OF MADRID The Community of Madrid is one of the seventeen autonomous communities (regions) of Spain. It is located at the centre of the country and the Castilian Central Plateau (Meseta Central). MADRID, CAPITAL OF SPAIN Madrid is the capital of Spain and the largest municipality, referred to as the Community of Madrid. The population of the city is almost 3.2 million with a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.5 million. The city is located on the Manzanares River in the centre of both the country and the Community of Madrid (which comprises the city of Madrid, and the extended suburbs and villages). As the capital city of Spain, seat of government, and residence of the Spanish monarch, Madrid is also the political, economic and cultural centre of Spain. Welcome LOCATION OF ACCOMMODATION Personnel who are accompanied by their families are accommodated in the Alcobendas area of Madrid. Some are located at the Encinar de los Reyes, and others at the Soto de la Moraleja. La Moraleja (El Encinar and El Soto) is a residential neighbourhood in the town of Alcobendas, northwest of Madrid. It is a very safe area where you can enjoy a relaxed atmosphere. British personnel serving unaccompanied are accommodated in Sanchinarro. -

A Case Study of Donana National Park, Andalucia, Spain and the Los Frailes Mine Toxic Spill of 1998

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1999 Volume VI: Human-Environment Relations: International Perspectives from History, Science, Politics, and Ethics Human-Environment Relations: A Case Study of Donana National Park, Andalucia, Spain and the Los Frailes Mine Toxic Spill of 1998 Curriculum Unit 99.06.01 by Stephen P. Broker Introduction. This curriculum unit on contemporary human-environment relations focuses on the interplay of cultural, ecological, environmental, and human health issues. It is a case study of an environmental disaster near Donana National Park, Andalucia, Spain. Donana is considered the most important wetland in Europe. Its marshes, mobile dunes, and forests are unique. In April 1998, a sudden burst in a zinc mine waste reservoir released a billion gallons of heavy metal contaminants into the Guadiamar River, a tributary of the Guadalquivir River, which forms the eastern boundary of Donana National Park. The toxic spill quickly was regarded as a national disaster in Spain, and it received extensive coverage in the press and in science journals. The highly acidic sludge, zinc, cadmium, arsenic, and lead pollutants that were released into the environment continue to threaten the ecology and the biota of this internationally significant wetland. I had the opportunity to visit Spain in the summer of 1998, just several months after the toxic spill occurred. The trip started and ended in Madrid, but the majority of time was spent traveling through the southern and southwestern regions of Spain, in Andalucia and Extremadura. A day excursion to Donana National Park gave me a chance to make first hand observations of the wetland (albeit during the dry season), to discuss ecological and environmental issues with park and tour group representatives, and to obtain some highly informative literature on the region. -

Basic Spanish for the Camino

BASIC SPANISH FOR THE CAMINO A Pilgrim’s Introduction to the Spanish Language and Culture American Pilgrims on the Camino www.americanpilgrims.org Northern California Chapter [email protected] February 1, 2020 Bienvenido peregrino Leaving soon on your Camino and need to learn some Spanish basics? Or perhaps you already know some Spanish and just need a refresher and some practice? In any case, here is a great opportunity to increase your awareness of the Spanish language and to prepare for your Camino and the transition into Spanish culture. Our meetings will focus on the language challenges that, as a pilgrim, you are likely to encounter on the Camino. While we will talk about culture, history, food, wine and many other day-to-day aspects of Spanish life, our objective will be to increase your language skills. Familiarity with the Spanish spoken in Spain will make the cultural transition easier for you and ultimately pay off with more satisfying human interactions along the Camino. Our meetings will be informal, in a comfortable environment and geared to making the review of Spanish an enjoyable experience. Buen Camino Emilio Escudero Northern California Chapter American Pilgrims on the Camino www.americanpilgrims.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Day 1 Agenda . i Day 2 Agenda . ii Day 3 Agenda . iii 01 - The Communities, Provinces and Geography of Spain . 1 02 - Spain - A Brief Introduction . 3 03 - A Brief History of Spain and the Camino de Santiago . 5 04 - Holidays and Observances in Spain 2020 . 11 05 - An Overview of the Spanish Language . 12 06 - Arabic Words Incorporated into Spanish . -

Geography in Spain

Belgeo 1 (2004) Special issue : 30th International Geographical Congress ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ Manuel Valenzuela, Manuel Mollá et Mª Luisa de Lázaro Geography in Spain ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ Avertissement Le contenu de ce site relève de la législation française sur la propriété intellectuelle et est la propriété exclusive de l'éditeur. Les œuvres figurant sur ce site peuvent être consultées et reproduites sur un support papier ou numérique sous réserve qu'elles soient strictement réservées à un usage soit personnel, soit scientifique ou pédagogique excluant toute exploitation commerciale. La reproduction devra obligatoirement mentionner l'éditeur, le nom de la revue, l'auteur et la référence du document. Toute autre reproduction est interdite sauf accord préalable de l'éditeur, en dehors des cas prévus par la législation en vigueur en France. Revues.org est un portail de revues en sciences humaines et sociales développé par le Cléo, Centre pour l'édition électronique ouverte (CNRS, EHESS, UP, UAPV). ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Course Information Teaching Staff Programme

COURSE INFORMATION GEOGRAPHY OF SPAIN Code number: 101010105 Degree in History Academic Year: 2018-2019 Compulsory course. 2nd year First semestre: 3 hours a week, 2 days a week 6 credits TEACHING STAFF Prof.: Ph. Dr. Alfonso M. Doctor Cabrera Department: History, Geography and Anthropology Office: Deanery, Faculty of Humanities Phone: 959 219046 E-mail: [email protected] Office hours: First Semester: Tuesday 16:00-19:00 / Wednesday 9:00-12:00 Second Semester: Tuesday 16:00-19:00 / Wednesday 9:00-12:00 PROGRAMME 1. DESCRIPTION Study and interpretation of physical, human and regional diversity of Geography of Spain: nature, population, countryside, cities, environment, landscapes, land planning and economic development, all in an European and global territorial framework. Characteristics and historical conformation of Spanish regions. 2. PREREQUISITES No requirements. Recommendation: use of print or digital maps and atlas. 3. OBJECTIVES/LEARNING OUTCOMES Generic skills: CG03. Ability to understand the geographical/historical and cultural diversity, and to promote tolerance and respect for each other’s values, which derive from different historical and cultural traditions. CG06. Ability to use resources for information survey, identification, array and gathering, and to use them to study and research in History and Geography. CG09. Proper use of geographical and historical vocabulary, and knowledge of other languages. CG10. Leading to skill training and professional practice of different potential outlets. Campus El Carmen Tel.: (+34) 959 21 94 94 [email protected] Avda. 3 de marzo, s/n 21007 Huelva Fax: (+34) 959 21 93 59 www.uhu.es/sric Specific skills: CE1. Ability to interprete and analyse societies in time and space dimension. -

Praise for a Child's Geography: Explore Medieval Kingdoms

䄀 䌀䠀䤀䰀䐀✀匀 䜀䔀伀䜀刀䄀倀䠀夀㨀 䔀堀倀䰀伀刀䔀 䴀吀 ⸀ 䔀䐀䤀䔀嘀䄀䰀 䬀䤀一䜀䐀伀䴀 䨀 伀 䠀 一 匀 伀 一 匀 Praise for A Child’s Geography: Explore Medieval Kingdoms... My eleven year old daughter and I were delighted to read through A Child’s Geography: Medieval Kingdoms. We both learned so very much! Reading this book really ignites the imagination and helps you feel like you are THERE, walking through the streets of the country being studied, tasting the local foods, and meeting new friends. My daughter was so interested in what we were reading that she begged to finish the book in one day! I am a trained classroom teacher that has been homeschooling for the past 18 years, and I would definitely place the Child’s Geography books up there with the very best resources—ones you and your child will return to over and over again. ~ Susan Menzmer This was my first time reading any books in the A Child’s Geography series and it will now be our new cur- riculum for geography as well as history. Beautifully written. The story pulls you in and allows you to fully immerse yourself in the places, sights, sounds, and scents of our world. The photographs are wonderful; beautiful, bright, and full of color. The book title says geography, but it is so much more. There is history and not boring text book history either. It’s edge of your seat history that you, as well as your children, will enjoy. I have learned so much and I am excited to get the whole collection to begin our journey around the world! ~ Stephanie Sanchez I really enjoyed getting some more indepth research about several areas that I have visited in person, either as a child or an adult. -

Spain Passport.Pdf

11 de febrero 2016 PROGRAMME OF EVENTS CATERING remain open all evening. Please do The Programme Centre Point Room not bring buggies, prams or push The International Evening will chairs into school but use the commence with a Fiesta Parade. outside routes. This is in the interest Pupils will meet in classrooms at of everyone’s safety particularly to 5:15pm and the parade will weave avoid a fire escape blockage. Please around the building to the South only use the internal routes to get to Chicken & Chorizo Playground. Pupils will be making the Hall and catering. masks etc. for the event, and we shall Paella - £2.50 be providing most of the costume The Hall requirements. Each class has a There will be six opportunities to watch different fiesta. and join in with flamenco in the hall. As FY: El dia de los Reyes / The day of in previous years we are inviting The Pupil Kitchen the three kings. guests by Family Surname. The order Year 1: La Tomatina " The World's of these is changed every year in Biggest Food Fight! order to be fair. Year 2: Spanish Food! 6:00pm Families with Surname Year 3: Noite dos Calacus: Night of beginning with S to Z the Pumpkins: 6:20pm Families with Surname Year 4: Las Fiestas de San Fermin. beginning with A to D Tapas Samples Celebrating the Bull. 6:40pm Families with Surname Year 5: La Feria del Caballo: Horse beginning with E to H Fair 7:00pm Families with Foundation (Each of the above will be led by a Stage Children with surnames I Mr Williams’ Room group of ten Year 6 pupils who will to R be creating the central float.) 7:20pm Families with Surname Parents are invited to stand beginning with I to L 7:40pm Families with Surname along the route which will be beginning with M to R Freshly Squeezed identified nearer the date. -

Název Prezentace

7. Tourist attractions in the Southern European. countries Předmět: The Tourist Attractions in the Czech Republic and in the World Opavě Geography of Portugal Mountains and high hills cover the northern third of Portugal, including an extension of the Cantabrian Mountains from Spain. The mainland's highest point is a peak in the Serra da Estrela, at 6,532 ft. (1,991m). Portugal's lowest point is along the Atlantic Ocean coastline. Portugal's overall highest point (Pico Volcano ) is located in the Azores (an autonomous region) on the island of Pico. It stands at (2,351 m). Further south and west, the land slopes to rolling hills and lowlands, and a broad coastal plain. The Algarve region in the far-south features mostly rolling plains, a few scattered mountains and some islands and islets. It's coastline is notable for limestone caves and grottoes. Major rivers in Portugal include the Douro, Guadiana, Mondego and the Tagus. There are no inland lakes, as water surfaces of size are dam-originated reservoirs. The main tourist attractions in Portugal Mosteiro dos Jerónimos, Lisbon - The Mosteiro dos Jerónimos is one of the country's most cherished and revered buildings, and a "must see' on every tourist's agenda. The church and monastery embody the spirit of the age, and feature some of the finest examples of Manueline architecture found anywhere in Portugal; the beautifully embellished decoration found on the South Portal is breathtaking. Arguably Portugal's most popular and family-friendly visitor attraction, Lisbon's oceanarium is brilliantly conceived to highlight the world's diverse ocean habitats. -

Everything You Never Wanted to Know About Spanish Wines (And a Few Things You Did) John Phillips Wacker University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected]

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Senior Theses Honors College Spring 2019 Everything You Never Wanted to Know About Spanish Wines (and a Few Things You Did) John Phillips Wacker University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses Part of the Basque Studies Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Food and Beverage Management Commons, and the Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Wacker, John Phillips, "Everything You Never Wanted to Know About Spanish Wines (and a Few Things You Did)" (2019). Senior Theses. 277. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses/277 This Thesis is brought to you by the Honors College at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Thesis Summary The Spanish wine scene is incredibly diverse, and an immense number of different wines are made in the country. Likewise, Spain is incredibly rich in culture, with a wide array of languages, histories, cultures, and cuisines found throughout the nation. The sheer number and variety of Spanish wines and the incredible variety of cultures found in Spain may be daunting to the uninitiated. Thus, a guide to Spanish wine and culture, which not only details the two but links them, as well, may prove very helpful to the Spanish wine newcomer or perhaps even a sommelier. This thesis-guide was compiled through the research of the various Denominaciones de Origen of Spain, the history of Spain, the regions of Spain and their individual histories and cultures, and, of course, the many, many wines of Spain. -

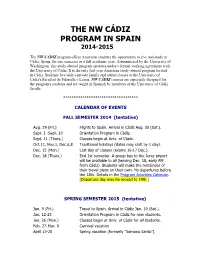

The Nw Cádiz Program in Spain

THE NW CÁDIZ PROGRAM IN SPAIN 2014-2015 The NW CÁDIZ program offers American students the opportunity to live and study in Cádiz, Spain, for one semester or a full academic year. Administered by the University of Washington, this study-abroad program operates under a formal working agreement with the University of Cádiz. It is the only full-year American study-abroad program located in Cádiz. Students live with a private family and attend classes at the University of Cádiz's Facultad de Filosofía y Letras. NW CÁDIZ courses are especially designed for the program's students and are taught in Spanish by members of the University of Cádiz faculty. *********************************** CALENDAR OF EVENTS FALL SEMESTER 2014 (tentative) Aug. 29 (Fri.) Flights to Spain. Arrival in Cádiz Aug. 30 (Sat.). Sept. 1 -Sept. 10 Orientation Program in Cádiz. Sept. 11 (Thurs.) Classes begin at Univ. of Cádiz. Oct.12, Nov.1, Dec.6,8 Traditional holidays (dates may shift by 1 day). Dec. 15 (Mon.) Last day of classes (exams 16-17 Dec.). Dec. 18 (Thurs.) End 1st semester. A group bus to the Jerez airport will be available to all (leaving Dec. 18, early AM from Cádiz). Students will make the remainder of their travel plans on their own. No departures before the 18th. Details in the Program Activities Calendar. [Departure day may be moved to 19th.] SPRING SEMESTER 2015 (tentative) Jan. 9 (Fri.) Travel to Spain. Arrival in Cádiz Jan. 10 (Sat.). Jan. 12-23 Orientation Program in Cádiz for new students. Jan. 26 (Mon.) Classes begin at Univ.