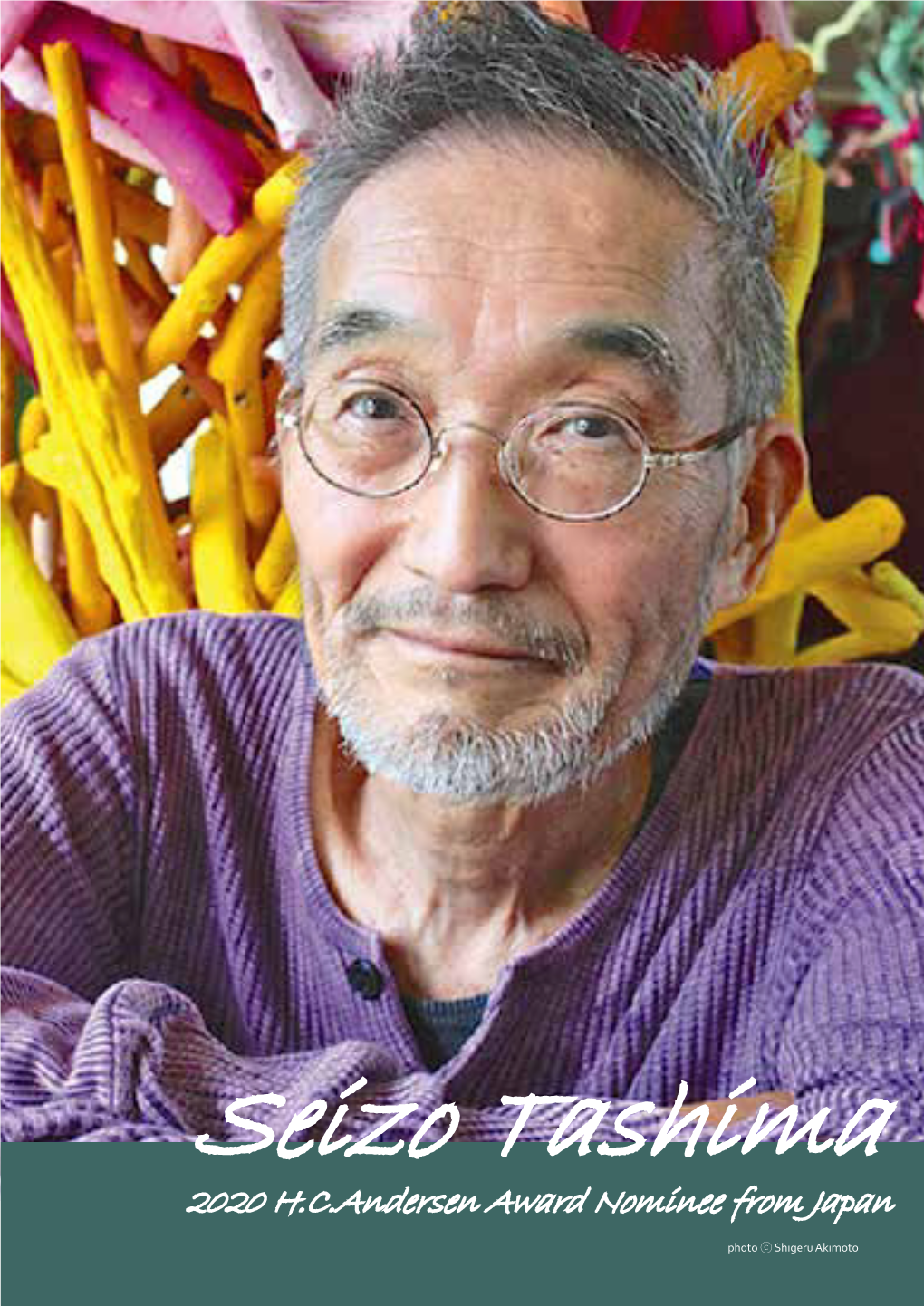

2020 H.C.Andersen Award Nominee from Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Master Keaton: Volume 10 Free

FREE MASTER KEATON: VOLUME 10 PDF Naoki Urasawa,Hokusei Katsushika | 322 pages | 06 Apr 2017 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781421585260 | English | San Francisco, United States Baka-Updates Manga - Master Keaton Remaster Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Master Keaton, Vol. Master Keaton, Vol. Takashi Nagasaki. Hokusei Katsushika Creator. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Master Keaton: Kanzenban 5. Other Editions 5. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Master Keaton, Vol. Be the first to Master Keaton: Volume 10 a question about Master Keaton, Vol. Lists with This Book. This book is not yet featured on Listopia. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 4. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Start your review of Master Keaton, Vol. Feb 15, Derek Royal rated it really liked it. Volume by volume, I'm making my way through Urasawa's Master Keaton series. A marked difference from his Monster is the episodic nature of this series. In the vast majority of its chapters, Keaton's adventures are stand-alone and can be appreciated outside of the context of the others. In some way, that's a strength of this title. On the other hand, I tend to appreciate more the longer-form stories involving Keaton, the ones that last two, three, or more segments. -

Pictures of an Island Kingdom Depictions of Ryūkyū in Early Modern Japan

PICTURES OF AN ISLAND KINGDOM DEPICTIONS OF RYŪKYŪ IN EARLY MODERN JAPAN A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ART HISTORY MAY 2012 By Travis Seifman Thesis Committee: John Szostak, Chairperson Kate Lingley Paul Lavy Gregory Smits Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter I: Handscroll Paintings as Visual Record………………………………. 18 Chapter II: Illustrated Books and Popular Discourse…………………………. 33 Chapter III: Hokusai Ryūkyū Hakkei: A Case Study……………………………. 55 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………. 78 Appendix: Figures …………………………………………………………………………… 81 Works Cited ……………………………………………………………………………………. 106 ii Abstract This paper seeks to uncover early modern Japanese understandings of the Ryūkyū Kingdom through examination of popular publications, including illustrated books and woodblock prints, as well as handscroll paintings depicting Ryukyuan embassy processions within Japan. The objects examined include one such handscroll painting, several illustrated books from the Sakamaki-Hawley Collection, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library, and Hokusai Ryūkyū Hakkei, an 1832 series of eight landscape prints depicting sites in Okinawa. Drawing upon previous scholarship on the role of popular publishing in forming conceptions of “Japan” or of “national identity” at this time, a media discourse approach is employed to argue that such publications can serve as reliable indicators of understandings -

Isum 許諾楽曲一覧 更新日:2019/1/23

ページ:1/37 ISUM 許諾楽曲一覧 更新日:2019/1/23 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM-1880-0537 JASRAC あの紙ヒコーキ くもり空わって ISUM-8212-1029 JASRAC SUNSHINE ISUM-9896-0141 JASRAC IT'S GONNA BE ALRIGHT ISUM-3412-4114 JASRAC あの青をこえて ISUM-5696-2991 JASRAC Thank you ISUM-9456-6173 JASRAC LIFE ISUM-4940-5285 JASRAC すべてへ ISUM-8028-4608 JASRAC Tomorrow ISUM-6164-2103 JASRAC Little Hero ISUM-5596-2990 JASRAC たいせつなひと ISUM-3400-5002 NexTone V.O.L ISUM-8964-6568 JASRAC Music Is My Life ISUM-6812-2103 JASRAC まばたき ISUM-0056-6569 JASRAC Wake up! ISUM-3920-1425 JASRAC MY FRIEND 19 ISUM-8636-1423 JASRAC 果てのない道 ISUM-5968-0141 NexTone WAY OF GLORY ISUM-4568-5680 JASRAC ONE ISUM-8740-6174 JASRAC 階段 ISUM-6384-4115 NexTone WISHES ISUM-5012-2991 JASRAC One Love ISUM-8528-1423 JASRAC 水・陸・そら、無限大 ISUM-1124-1029 JASRAC Yell ISUM-7840-5002 JASRAC So Special -Version AI- ISUM-3060-2596 JASRAC 足跡 ISUM-4160-4608 JASRAC アシタノヒカリ ISUM-0692-2103 JASRAC sogood ISUM-7428-2595 JASRAC 背景ロマン ISUM-5944-4115 NexTone ココア by MisaChia ISUM-1020-1708 JASRAC Story ISUM-0204-5287 JASRAC I LOVE YOU ISUM-7456-6568 NexTone さよならの前に ISUM-2432-5002 JASRAC Story(English Version) 369 AAA ISUM-0224-5287 JASRAC バラード ISUM-3344-2596 NexTone ハレルヤ ISUM-9864-0141 JASRAC VOICE ISUM-9232-0141 JASRAC My Fair Lady ft. May J. "E"qual ISUM-7328-6173 NexTone ハレルヤ -Bonus Tracks- ISUM-1256-5286 JASRAC WA Interlude feat.鼓童,Jinmenusagi AI ISUM-5580-2991 JASRAC サンダーロード ↑THE HIGH-LOWS↓ ISUM-7296-2102 JASRAC ぼくの憂鬱と不機嫌な彼女 ISUM-9404-0536 JASRAC Wonderful World feat.姫神 ISUM-1180-4608 JASRAC Nostalgia -

Stardigio Program

スターデジオ チャンネル:408 J-POPピックアップアーティスト 放送日:2019/07/15~2019/07/21 「番組案内 (8時間サイクル)」 開始時間:4:00〜/12:00〜/20:00〜 楽曲タイトル 演奏者名 ■MAN WITH A MISSION 特集(1) NEVER FXXKIN' MIND THE RULES MAN WITH A MISSION 1997 MAN WITH A MISSION DANCE EVERYBODY MAN WITH A MISSION Smells Like Teen Spirit MAN WITH A MISSION Feel and Think MAN WITH A MISSION distance MAN WITH A MISSION フォーカスライト MAN WITH A MISSION FROM YOUTH TO DEATH MAN WITH A MISSION Get Off of My Way MAN WITH A MISSION Emotions MAN WITH A MISSION database ~アニメ「ログ・ホライズン」OPテーマ~ MAN WITH A MISSION feat. TAKUMA (10-FEET) higher MAN WITH A MISSION Seven Deadly Sins ~アニメ「七つの大罪」OPテーマ~ MAN WITH A MISSION Dive MAN WITH A MISSION ■MAN WITH A MISSION 特集(2) Out of Control MAN WITH A MISSION×Zebrahead Raise your flag ~アニメ「機動戦士ガンダム MAN WITH A MISSION 鉄血のオルフェンズ」OPテーマ~ Memories MAN WITH A MISSION Survivor MAN WITH A MISSION Dead End in Tokyo MAN WITH A MISSION My Hero MAN WITH A MISSION Find You MAN WITH A MISSION Take Me Under MAN WITH A MISSION Winding Road ~アニメ「ゴールデンカムイ」OPテーマ~ MAN WITH A MISSION Freak It! MAN WITH A MISSION feat. 東京スカパラダイスオーケストラ Remember Me MAN WITH A MISSION Left Alive MAN WITH A MISSION スターライト・シンドローム MAN WITH A MISSION FLY AGAIN 2019 MAN WITH A MISSION ■Superfly 特集(1) ハロー・ハロー Superfly マニフェスト Superfly i spy i spy Superfly×JET 愛をこめて花束を Superfly Hi-Five Superfly How Do I Survive? Superfly My Best Of My Life Superfly 恋する瞳は美しい Superfly やさしい気持ちで Superfly Alright!! Superfly Dancing On The Fire Superfly Wildflower Superfly タマシイレボリューション Superfly You & Me Superfly ■Superfly 特集(2) Eyes On Me ~ゲーム「The 3rd Birthday」テーマソング~ -

A Thesis Entitled Yoshimoto Taka'aki, Communal Illusion, and The

A Thesis entitled Yoshimoto Taka’aki, Communal Illusion, and the Japanese New Left by Manuel Yang Submitted as partial fulfillment for requirements for The Master of Arts Degree in History ________________________ Adviser: Dr. William D. Hoover ________________________ Adviser: Dr. Peter Linebaugh ________________________ Dr. Alfred Cave ________________________ Graduate School The University of Toledo (July 2005) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is customary in a note of acknowledgments to make the usual mea culpa concerning the impossibility of enumerating all the people to whom the author has incurred a debt in writing his or her work, but, in my case, this is far truer than I can ever say. This note is, therefore, a necessarily abbreviated one and I ask for a small jubilee, cancellation of all debts, from those that I fail to mention here due to lack of space and invidiously ungrateful forgetfulness. Prof. Peter Linebaugh, sage of the trans-Atlantic commons, who, as peerless mentor and comrade, kept me on the straight and narrow with infinite "grandmotherly kindness" when my temptation was always to break the keisaku and wander off into apostate digressions; conversations with him never failed to recharge the fiery voltage of necessity and desire of historical imagination in my thinking. The generously patient and supportive free rein that Prof. William D. Hoover, the co-chair of my thesis committee, gave me in exploring subjects and interests of my liking at my own preferred pace were nothing short of an ideal that all academic apprentices would find exceedingly enviable; his meticulous comments have time and again mercifully saved me from committing a number of elementary factual and stylistic errors. -

A Historical Analysis of the Traditional Japanese Decision-Making Process in Contrast with the U.S

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1976 A historical analysis of the traditional Japanese decision-making process in contrast with the U.S. system and implications for intercultural deliberations Shoji Mitarai Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Mitarai, Shoji, "A historical analysis of the traditional Japanese decision-making process in contrast with the U.S. system and implications for intercultural deliberations" (1976). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 2361. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.2358 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Shoji Mitarai for the Master of Arts in Speech Conununication presented February 16, 1976. Title: A Historical Analysis of the Traditional Japanese Decision-Maki~g Process in Contrast with the U.S. System and Implications for Intercultural Delibera tions. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEES: The purpose of this research.is to (1) describe and analyze the different methods used by Japanese ·and by U.S. persons to reach ~greement in small. group deliberations, (2) discover the depth of ·conunitment and personal involvement with th~se methods by tracing their historical b~ginni~gs, and (3) draw implications 2 from (1) and (2) as to probability of success of current problem solving deliberations involving members of both ·groups. -

Childbearing in Japanese Society: Traditional Beliefs and Contemporary Practices

Childbearing in Japanese Society: Traditional Beliefs and Contemporary Practices by Gunnella Thorgeirsdottir A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Social Sciences School of East Asian Studies August 2014 ii iii iv Abstract In recent years there has been an oft-held assumption as to the decline of traditions as well as folk belief amidst the technological modern age. The current thesis seeks to bring to light the various rituals, traditions and beliefs surrounding pregnancy in Japanese society, arguing that, although changed, they are still very much alive and a large part of the pregnancy experience. Current perception and ideas were gathered through a series of in depth interviews with 31 Japanese females of varying ages and socio-cultural backgrounds. These current perceptions were then compared to and contrasted with historical data of a folkloristic nature, seeking to highlight developments and seek out continuities. This was done within the theoretical framework of the liminal nature of that which is betwixt and between as set forth by Victor Turner, as well as theories set forth by Mary Douglas and her ideas of the polluting element of the liminal. It quickly became obvious that the beliefs were still strong having though developed from a person-to- person communication and into a set of knowledge aquired by the mother largely from books, magazines and or offline. v vi Acknowledgements This thesis would never have been written had it not been for the endless assistance, patience and good will of a good number of people. -

December 11, 2018 201 W

A G E N D A CITY OF AZTEC CITY COMMISSION WORKSHOP December 11, 2018 201 W. Chaco, City Hall 5:15 p.m. 5:15 p.m. A. Aztec Municipal Golf Course Discussion ATTENTION PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES: The meeting room and facilities are fully accessible to persons with mobility disabilities. If you plan to attend the meeting and will need an auxiliary aid or service, please contact the City Clerk's Office at 334-7600 prior to the meeting so that arrangements can be made. Note: A final agenda will be posted 72 hours prior to the meeting. Copies of the agenda may be obtained from City Hall, 201 W. Chaco, Aztec, NM 87410. Staff Summary Report MEETING DATE: December 11, 2018 AGENDA ITEM: Workshop AGENDA TITLE: Aztec Municipal Golf Course Discussion ACTION REQUESTED BY: ACTION REQUESTED: None – Discussion Only SUMMARY BY: PROJECT DESCRIPTION / FACTS The City of Aztec entered into an agreement to operate the Aztec Municipal Golf Course, formerly known as Hidden Valley Golf Course, in February 2015. The lease agreement for the course between HVCC and the City was initially executed in February 2015 and was a two year agreement. A new agreement was executed in April 2017. The City was the primary operator of the course until December 2016 at which time the City executed an agreement with Randy Hodge dba Ruby’s in the Valley to provide management services. Golf Course Discussion Summary Hidden Valley Golf Course: Current Golf Course Lease Agreement summary between HVCC and City of Aztec Agreement commenced on May 1, 2017 and expires February 28, 2019 with renewal options. -

The Symbol of the Dragon and Ways to Shape Cultural Identities in Institute Working Vietnam and Japan Paper Series

2015 - HARVARD-YENCHING THE SYMBOL OF THE DRAGON AND WAYS TO SHAPE CULTURAL IDENTITIES IN INSTITUTE WORKING VIETNAM AND JAPAN PAPER SERIES Nguyen Ngoc Tho | University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vietnam National University – Ho Chi Minh City THE SYMBOL OF THE DRAGON AND WAYS TO SHAPE 1 CULTURAL IDENTITIES IN VIETNAM AND JAPAN Nguyen Ngoc Tho University of Social Sciences and Humanities Vietnam National University – Ho Chi Minh City Abstract Vietnam, a member of the ASEAN community, and Japan have been sharing Han- Chinese cultural ideology (Confucianism, Mahayana Buddhism etc.) and pre-modern history; therefore, a great number of common values could be found among the diverse differences. As a paddy-rice agricultural state of Southeast Asia, Vietnam has localized Confucianism and absorbed it into Southeast Asian culture. Therefore, Vietnamese Confucianism has been decentralized and horizontalized after being introduced and accepted. Beside the local uniqueness of Shintoism, Japan has shared Confucianism, the Indian-originated Mahayana Buddhism and other East Asian philosophies; therefore, both Confucian and Buddhist philosophies should be wisely laid as a common channel for cultural exchange between Japan and Vietnam. This semiotic research aims to investigate and generalize the symbol of dragons in Vietnam and Japan, looking at their Confucian and Buddhist absorption and separate impacts in each culture, from which the common and different values through the symbolic significances of the dragons are obviously generalized. The comparative study of Vietnamese and Japanese dragons can be enlarged as a study of East Asian dragons and the Southeast Asian legendary naga snake/dragon in a broader sense. The current and future political, economic and cultural exchanges between Japan and Vietnam could be sped up by applying a starting point at these commonalities. -

Amaterasu-Ōmikami (天照大御神), in His Quest to Slay the Eight-Headed Serpent Demon Yamata-No-Orochi (八岐大蛇) in Izumo Province (出雲国)

Northeast Asian Shamanism 神道, 신도, 御嶽信仰, 神教, & ᡝᡝᡝᡝ ‘Lady’ Minami “Danni” Kurosaki (黒崎美波、お巫女様) ⛩ My Personal History & Involvement The Kurosaki Clan (黒崎の一族) ● Our earliest ancestor was directly involved with assisting the warrior god Susanō-no-Mikoto (須佐之 男命), the disgraced brother of sun goddess Amaterasu-Ōmikami (天照大御神), in his quest to slay the eight-headed serpent demon Yamata-no-Orochi (八岐大蛇) in Izumo Province (出雲国) ● Since then, the Kurosaki clan has been one of a few influential families in the history of Shintoism throughout Ancient and Feudal Japan ● We are a part of the Ten Sacred Treasures (十種の神宝) of Japanese history; our treasure that was offered to Susanō is the Dragon-repelling Shawl (大蛇ノ比礼) Inheritance of Kannushi/Miko-ship ● Because of our family’s status in traditional Japan after that event, heirship and training is passed down through the branches of the family on who will be the next Danshi kannushi (男子神主, Male Priest), Joshi kannushi (女子神主, Female Priestess), Miko (巫女, Female Shaman/Shrine Maiden) or Danfu (男巫, Male Shaman/Shrine Valet) in that generational line ● Not all kannushi and miko come from a long family line - anyone can be a part of the Shintō clergy granted they apply and go through proper training! ● I belong to a branch of the family, and as the oldest child in my generational line, I am next to succeed the title of (matriarch/patriarch) for my immediate family ● The current matriarch of our entire the clan is Miu Kurosaki, and the current matriarch of my direct immediate family is Hikaru Kurosaki (Luz -

Introduction to Manga for Librarians

PRESENTS AN INTRODUCTION TO MANGA FOR LIBRARIANS In cooperation with Hello, we’re We’re extremely excited to now have our entire digital book list available to libraries through OverDrive. Kodansha is one of the leading publishers in Japan, and one of the largest in the world. While we are a general publisher, we are also one of the major publishers of Japanese comics, or manga, with a long and distinguished history of releasing some the most popular titles in the world, including such classics as Sailor Moon, Akira, and most recently, Attack on Titan. This brief introduction covers manga titles available from our U.S.-based manga imprint, Kodansha Comics, which publishes selected manga from our broader Japanese list into the English-reading world. While the wide variety of genres (for all audiences) and long, complex storylines of manga can be bewildering for the uninitiated, we hope to break down some basic concepts here. In particular, we hope you take away from here a few key points about manga, and in particular digital manga, if you’re not familiar with them already: MANGA ARE THE KIND OF COMICS YOUNG WOMEN LIKE TO READ. Unlike most Western comics, manga is made for all categories, catering to all audiences, from young children to adults, girls and boys. In particular, manga has exposed the stereotype in North America that girls don’t like comics and are often the preferred type of comics young women like to read. MANGA SPEAKS TO TEENS. That said, teenagers are the core demographic of manga in the West. -

A Study of Proposition and Modality Focusing on Epistemic Modals in the Japanese Language

A Study of Proposition and Modality Focusing on Epistemic Modals in the Japanese Language Kazuyuki Matsushita A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University March 2006 Declaration Except where it is otherwise acknowledged in the text, this thesis is entirely my own work Kazuyuki Matsushita March, 2006 Acknowledgements I would like to express my deepest thanks to my supervisor Dr. Peter Hendriks. He has given precious advice, and encouragement throughout my candidature. In particular, he has provided me with suitable terms to solve semantic gaps between English and Japanese. I am grateful for the time he has spent on my behalf. I wish to thank my associate supervisor Dr. Nicolette Bramley of the University of Canberra, who has provided excellent advice and criticism to improve my draft. I could not have done without Dr. Gail Craswell, at the Academic Skills and Learning Centre, who reviewed my thesis and made significant comments on my drafts. I am also grateful to Dr. Meredith McKinney, who has carefully proofread my draft. I would like to thank Prof. Junsaku Fundō and the late Prof. Kazuo Suzuki, who have given me encouragement to continue my studies since I studied at Tokyo Kyōiku University. Finally, I want to express my gratitude to my wife Sachiko, who read my draft conscientiously, pointed out inappropriate examples, and has supported me through hard times and good times. Canberra, Australia March 2006 Kazuyuki Matsushita ii Abstract This study discusses proposition and modality in the Japanese language, focusing on epistemic modals. In the literature of modality recently, detailed discussions of individual modals have been made to clarify their function.