Fruitless Attempts. the Kurdish Initiative and the Containment of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identity, Narrative and Frames: Assessing Turkey's Kurdish Initiatives

ARTICLE IDENTITY, NARRATIVE AND FRAMES: ASSESSING TURKEY’S KURDISH INITIATIVES Identity, Narrative and Frames: Assessing Turkey’s Kurdish Initiatives JOHANNA NYKÄNEN* ABSTRACT In 2009 the Turkish government launched a novel initiative to tackle the Kurdish question. The initiative soon ran into deadlock, only to be un- tangled towards the end of 2012 when a new policy was announced. This comparative paper adopts Michael Barnett’s trinity of identity, narratives and frames to show how a cultural space within which a peaceful engage- ment with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) would be deemed legiti- mate and desirable was carved out. Comparisons between the two policies reveal that the framing of policy narratives can have a formative impact on their outcomes. The paper demonstrates how the governing quality of firmness fluctuated between different connotations and references, finally leading back to a deep-rooted tradition in Turkish governance. ince 1984 when the PKK commenced its armed struggle against the Turkish state, Turkish security policies have been framed around the SKurdish question with the PKK presented as the primary security threat to be tackled. Turkey’s Kurdish question has its roots in the founding of the republic in 1923, which saw Kurdish ethnicity assimilated with Turkishness. In accordance with the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), only three minorities were and continue to be officially recognized in Turkey: Armenians, Jews and Greeks. These three groups were granted minority status on the basis of their religion. Kurdish identity – whether national, racial or ethnic – was not recognized by the republic, resulting in decades of uprisings by the Kurds and oppressive and * Department assimilative politics by the state. -

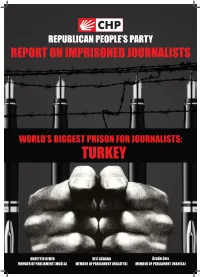

Report on Imprisoned Journalists

REPUBLICAN PEOPLE’S PARTY REPORT ON IMPRISONED JOURNALISTS WORLD’S BIGGEST PRISON FOR JOURNALISTS: TURKEY NURETTİN DEMİR VELİ AĞBABA ÖZGÜR ÖZEL MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT (MUĞLA) MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT (MALATYA) MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT (MANİSA) REPUBLICAN PEOPLE’S PARTY PRISON EXAMINATION AND WATCH COMMISSION REPORT ON IMPRISONED JOURNALISTS WORLD’S BIGGEST PRISON FOR JOURNALISTS: TURKEY NURETTİN DEMİR VELİ AĞBABA ÖZGÜR ÖZEL MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT (MUĞLA) (MALATYA) (MANİSA) CONTENTS PREFACE, Ercan İPEKÇİ, General Chairman of the Union of Journalists in Turkey ....... 3 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 11 2. JOURNALISTS IN PRISON: OBSERVATIONS AND FINDINGS .................. 17 3. JOURNALISTS IN PRISON .......................................................................... 21 3.1 Journalists Put on Trial on Charges of Committing an Off ence against the State and Currently Imprisoned ................................................................................ 21 3.1.1Information on a Number of Arrested/Sentenced Journalists and Findings on the Reasons for their Arrest ........................................................................ 21 3.2 Journalists Put on Trial in Association with KCK (Union of Kurdistan Communities) and Currently Imprisoned .................................... 32 3.2.1Information on a Number of Arrested/Sentenced Journalists and Findings on the Reasons for their Arrest ....................................................................... -

Global Turkey in Europe. Political, Economic, and Foreign Policy

ISSN 2239-2122 9 IAI Research Papers The EU is changing, Turkey too, and - above all - there is systemic change and crisis all G round, ranging from economics, the spread of democratic norms and foreign policy. LOBAL The IAI Research Papers are brief monographs written by one or N.1 European Security and the Future of Transatlantic Relations, This research paper explores how the EU and Turkey can enhance their cooperation in more authors (IAI or external experts) on current problems of inter- T edited by Riccardo Alcaro and Erik Jones, 2011 URKEY GLOBAL TURKEY national politics and international relations. The aim is to promote the political, economic, and foreign policy domains and how they can find a way out of the stalemate EU-Turkey relations have reached with the lack of progress in accession greater and more up to date knowledge of emerging issues and N. 2 Democracy in the EU after the Lisbon Treaty, IN trends and help prompt public debate. edited by Raaello Matarazzo, 2011 negotiations and the increasing uncertainty over both the future of the European project E after the Eurozone crisis and Turkey’s role in it. UROPE IN EUROPE N. 3 The Challenges of State Sustainability in the Mediterranean, edited by Silvia Colombo and Nathalie Tocci, 2011 A non-profit organization, IAI was founded in 1965 by Altiero Spinel- li, its first director. N. 4 Re-thinking Western Policies in Light of the Arab Uprisings, SENEM AYDIN-DÜZGIT is Assistant Professor at the Istanbul Bilgi University and Senior POLITICAL, ECONOMIC, AND FOREIGN POLICY edited by Riccardo Alcaro and Miguel Haubrich-Seco, 2012 Research Affiliate of the Istanbul Policy Centre (IPC). -

Turkey Page 1 of 29

2010 Human Rights Report: Turkey Page 1 of 29 Home » Under Secretary for Democracy and Global Affairs » Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor » Releases » Human Rights Reports » 2010 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices » Europe and Eurasia » Turkey 2010 Human Rights Report: Turkey BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR 2010 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices April 8, 2011 Turkey, with a population of approximately 74 million, is a constitutional republic with a multiparty parliamentary system and a president with limited powers. The Justice and Development Party (AKP) formed a parliamentary majority in 2007 under Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control of the security forces. There were reports of a number of human rights problems and abuses in the country. Security forces committed unlawful killings; the number of arrests and prosecutions in these cases was low compared to the number of incidents, and convictions remained rare. During the year human rights organizations reported cases of torture, beatings, and abuse by security forces. Prison conditions improved but remained poor, with overcrowding and insufficient staff training. Law enforcement officials did not always provide detainees immediate access to attorneys as required by law. There were reports that some officials in the elected government and state bureaucracy at times made statements that some observers believed influenced the independence of the judiciary. The overly close relationship between judges and prosecutors continued to hinder the right to a fair trial. Excessively long trials were a problem. The government limited freedom of expression through the use of constitutional restrictions and numerous laws. -

EU-Turkey Relations and the Stagnation of Turkish Democracy

EU-Turkey Relations and the Stagnation of Turkish Democracy Senem Aydın-Düzgit and E. Fuat Keyman Istanbul Bilgi University and Sabanci University WORKING PAPER 02 EU-Turkey Relations and the Stagnation of Turkish Democracy Senem Aydın-Düzgit and E. Fuat Keyman* Turkey EU Accession Process Democracy Deficit Abstract Introduction The current stagnation of Turkish democracy goes hand in hand with the current impasse in EU-Turkey relations. A combination of domestic Back in August 2004, we published a working paper on the role of factors with a loss of credibility of EU conditionality led to a situation Turkey’s relations with the EU in transforming Turkish democracy in which political reform is substantially stalled and in cases where it as part of a larger project on EU-Turkey relations conducted by the is realised, it is mostly conducted to serve the interests of the ruling Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) and the Economics and political elite and with no real reference to the EU. The virtuous cycle of Foreign Policy Forum (Aydın and Keyman 2004). The central argument reform that characterised the 1999-2005 period has been replaced by of the paper was that the strengthening credibility of EU conditionality a vicious cycle in which lack of effective conditionality feeds into po- towards Turkey, coupled with favourable domestic and international litical stagnation which in turn moves Turkey and the EU further away dynamics resulted in substantial reforms towards the consolidation from one another. of Turkish democracy. The paper, written prior to the EU’s decision to open accession negotiations with Turkey, concluded that the opening of accession talks with the country on the basis of a fair decision that rests on Turkey’s achievements in its modernity and democracy would constitute a crucial step in remedying the remaining problematic aspects of Turkish democracy. -

The Collapse of the Peace Process with the Kurds in Turkey

Back to Square One? The Collapse of the Peace Process with the Kurds in Turkey Gallia Lindenstrauss The Kurdish question is one of the fundamental problems, if not the most important, facing the Turkish republic. Since the 1980s, some 40,000 people have been killed in the violent struggle between Turkey’s central government and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, the PKK. Serious efforts were made to promote solutions during the tenure of President Turgut Ozal in the early 1990s, but since its rise to power in 2002, the Justice and Development Party has made the most progress on the issue compared to previous governments. Since 2008, and in greater intensity since the end of 2012, Turkey promoted a peace process between the government and the Kurdish minority. However, in July 2015, the process collapsed, leading to renewed violence between the sides, especially in the southeast of the country. Compared to the past, the PKK is putting more emphasis on urban warfare. Consequently, one of the Turkish army’s reactions to the renewed hostilities has been to impose an extended curfew on several neighborhoods and towns with a Kurdish majority, which severely disrupts the population’s routine of life. While past talks between the government and the Kurdish minority have also ended without a resolution and have seen the resumption of fighting, it seems that this time the escalation is more acute. Statements such as that made by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan that Turkey’s objective is “to annihilate” the armed Kurds 1 raise concern that it will be extremely difficult to revive the peace process anytime soon. -

Anatomy of a Civil War

Revised Pages Anatomy of a Civil War Anatomy of a Civil War demonstrates the destructive nature of war, rang- ing from the physical destruction to a range of psychosocial problems to the detrimental effects on the environment. Despite such horrific aspects of war, evidence suggests that civil war is likely to generate multilayered outcomes. To examine the transformative aspects of civil war, Mehmet Gurses draws on an original survey conducted in Turkey, where a Kurdish armed group, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), has been waging an intermittent insurgency for Kurdish self- rule since 1984. Findings from a probability sample of 2,100 individuals randomly selected from three major Kurdish- populated provinces in the eastern part of Turkey, coupled with insights from face-to- face in- depth inter- views with dozens of individuals affected by violence, provide evidence for the multifaceted nature of exposure to violence during civil war. Just as the destructive nature of war manifests itself in various forms and shapes, wartime experiences can engender positive attitudes toward women, create a culture of political activism, and develop secular values at the individual level. Nonetheless, changes in gender relations and the rise of a secular political culture appear to be primarily shaped by wartime experiences interacting with insurgent ideology. Mehmet Gurses is Associate Professor of Political Science at Florida Atlantic University. Revised Pages Revised Pages ANATOMY OF A CIVIL WAR Sociopolitical Impacts of the Kurdish Conflict in Turkey Mehmet Gurses University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © 2018 by Mehmet Gurses All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. -

The Unspoken Truth

THE UNSPOKEN TRUTH: DISAPPEARANCES ENFORCED One of the foremost obstacles As the Truth Justice Memory Center, we aim to, in the path of Turkey’s process ■ Carry out documentation work of democratization is the fact regarding human rights violations that have taken place in the past, to publish THE UNSPOKEN that systematic and widespread and disseminate the data obtained, and to demand the acknowledgement human rights violations are of these violations; not held to account, and ■ Form archives and databases for the use of various sections of society; victims of unjust treatments TRUTH: ■ Follow court cases where crimes are not acknowledged and against humanity are brought to trial and to carry out analyses and develop compensated. Truth Justice proposals to end the impunity of public officials; Memory Center contributes ■ Contribute to society learning ENFORCED to the construction of a the truths about systematic and widespread human rights violations, democratic, just and peaceful and their reasons and outcomes; and to the adoption of a “Never present day society by Again” attitude, by establishing a link between these violations and the supporting the exposure of present day; DISAPPEAR- systematic and widespread ■ Support the work of civil society organizations that continue to work human rights violations on human rights violations that have taken place in the past, and reinforce that took place in the past the communication and collaboration between these organizations; with documentary evidence, ANCES ■ Share experiences formed in the reinforcement of social different parts of the world regarding transitional justice mechanisms, and ÖZGÜR SEVGİ GÖRAL memory, and the improvement initiate debates on Turkey’s transition period. -

Trans Fatty Acid Composition of Southeastern Anatolia Region

Determination of the Accumulated Oil and (CIS)-Trans Fatty Acid Composition of Southeastern Anatolia Region Sirnak Province Olive Genotype Through Capillary Column Gas Chromatography Method 1 1 2 3 4 Ebru Sakar , Bekir Erol Ak , Mehmet Ulaş , Kürşat Alp Aslan Abidin Tatlı 1 Harran University Department of Horticulture, Faculty of Agriculture, Sanliurfa Turkey 2 3 Bornova Olive Research Station, Izmir -Turkey Gaziantep Peanut Research Station, 4 Gaziantep -Turkey Biological Combat Research Station, Adana -Turkey Many factors contribute to the production of a good quality olive oil, including the region olives are grown, the type of olives, climate and changes in its annual rate, harvest time, harvest method, transportation of olives to the processing facility and processing method itself. The primal effects of geographical location and climate rest in their contribution to the fat level the fruit can reach: olives grown in different regions yield oils of different fat levels, therefore creating a difference in the quality of the oil. Random olive fruits of 34 different olive genotypes from Silopi, Uludere and Cizre towns of Sirnak province were handpicked from all over the trees (which were designated at the time of harvest) and the samples placed in 250 gram polyethylene bags placed among ice cubes were transported to the lab on the same day, kept in store in -20 Celsius degrees until studied in a deep freezer. The thawed olives were studied in the same day and were not frozen again. Maximum accumulated fat was observed in N. hasko-9 type with a 8.8%, and lowest in N.hasko-3. -

The Ideological Discourse of the Islamist Humor Magazines in Turkey: the Case of Misvak

THE IDEOLOGICAL DISCOURSE OF THE ISLAMIST HUMOR MAGAZINES IN TURKEY: THE CASE OF MISVAK A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY NAZLI HAZAL TETİK IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF MEDIA AND CULTURAL STUDIES JULY 2020 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Yaşar Kondakçı Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Barış Çakmur Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Dr. Necmi Erdoğan Supervisor Examining Committee Members Assist. Prof. Dr. Özgür Avcı (METU, PADM) Prof. Dr. Necmi Erdoğan (METU, PADM) Prof. Dr. Lütfi Doğan Tılıç (Başkent Uni., ILF) PLAGIARISM I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name: Nazlı Hazal Tetik Signature: iii ABSTRACT THE IDEOLOGICAL DISCOURSE OF THE ISLAMIST HUMOR MAGAZINES IN TURKEY: THE CASE OF MISVAK Tetik, Nazlı Hazal M.S., Department of Media and Cultural Studies Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Necmi Erdoğan July 2020, 259 pages This thesis focuses on the ideological discourse of Misvak, one of the most popular Islamist humor magazines in Turkey in the 2000s. -

Turkey: End Abusive Operations Under Indefinite Curfews

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL BRIEFING AI Index: EUR 44/3230/2016 Turkey: End abusive operations under indefinite curfews Amnesty International calls on the Turkish government to end the indefinite curfews in Kurdish neighbourhoods across east and south-east Turkey. For several months, Amnesty International has been urging the government to end disproportionate restrictions on movement, including round-the- clock curfews, and other arbitrary measures which have left residents without access to emergency health care, food, water and electricity for extended periods. The draconian restrictions imposed during indefinite curfews, some of which have been in place for over a month, increasingly resemble collective punishment, and must end. Operations by police and the military in these areas have been characterised by abusive use of force, including firing heavy weaponry in residential neighbourhoods. The Turkish government must ensure that any use of firearms is human rights compliant, and doesn’t lead to the deaths and injuries of unarmed residents. More than 150 residents have reportedly been killed as state forces have clashed with Revolutionary Patriotic Youth Movement (YDG-H), the youth wing of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). The dead include women, young children and the elderly casting serious doubt over the government’s claims that very few of the dead were unarmed. The battles take place in the context of armed clashes taking place between the security services and the PKK, following the breakdown in July 2015 of a peace process that had held in place since 2013. PKK attacks have resulted in the deaths of civilians. On 13 January an attack by the PKK left one police officer and five civilians, including two young children, dead when they planted a car bomb outside the Çınar police headquarters in Diyarbakır province. -

Towards a Resolution: an Assessment of Possibilities, Opportunities and Problems

TURKEY PEACE ASSEMBLY TOWARDS A RESOLUTION: AN ASSESSMENT OF POSSIBILITIES, OPPORTUNITIES AND PROBLEMS Assoc. Dr. Ayşe Betül Çelik Sabancı University, Department Member Murat Çelikkan Journalist-Centre for Truth Justice Memory Assoc.Prof. Evren Balta Yıldız Technical University, Department Member Assist.Prof. Nil Mutluer Nişantaşı University, Department Member Assoc. Prof. Levent Korkut Medipol University, Department Member Turkey Peace Assembly NOVEMBER 2015 [email protected] | [email protected] +90 (212) 249 2654 www.turkiyebarismeclisi.com /Baris_Meclisi 1 TOWARDS A RESOLUTION AN ASSESSMENT OF POSSIBILITIES, OPPORTUNITIES AND PROBLEMS This report covers the resolution/peace process that took place between the years of 2013 and 2015 in Turkey. It was the first time that the Turkish army and the PKK experienced bilateral ceasefire. This work aimed to contribute to the peace process in the transformation of the ceasefire into a negotiation process. After this report had been written, in President Erdoğan’s words the peace process has been put into deep freeze. And now, peace process had changed into a violent process in Turkey. There have been street clashes, deaths, bombings and all-out massacres. Local mayors and politicians were arrested by the state. More then hundred people were killed in Ankara and Suruç blasts. Diyarbakır Bar President Tahir Elçi was killed while he was making a press statement asking an end to violence. This violent atmosphere under- mined the efforts of democratic powers, NGOs, and peace groups. The report which was written before the start of the violence tried to draw the attention of the actors to the shortcomings and dangers in the peace process.