Winter Journal 2017 – Issue No. 13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

On Modernity, Identity and White-Collar Boxing. Phd

From Rookie to Rocky? On Modernity, Identity and White-Collar Boxing Edward John Wright, BA (Hons), MSc, MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. September, 2017 Abstract This thesis is the first sociological examination of white-collar boxing in the UK; a form of the sport particular to late modernity. Given this, the first research question asked is: what is white-collar boxing in this context? Further research questions pertain to social divisions and identity. White- collar boxing originally takes its name from the high social class of its practitioners in the USA, something which is not found in this study. White- collar boxing in and through this research is identified as a practice with a highly misleading title, given that those involved are not primarily from white-collar backgrounds. Rather than signifying the social class of practitioner, white-collar boxing is understood to pertain to a form of the sport in which complete beginners participate in an eight-week boxing course, in order to compete in a publicly-held, full-contact boxing match in a glamorous location in front of a large crowd. It is, thus, a condensed reproduction of the long-term career of the professional boxer, commodified for consumption by others. These courses are understood by those involved to be free in monetary terms, and undertaken to raise money for charity. As is evidenced in this research, neither is straightforwardly the case, and white-collar boxing can, instead, be understood as a philanthrocapitalist arrangement. The study involves ethnographic observation and interviews at a boxing club in the Midlands, as well as public weigh-ins and fight nights, to explore the complex interrelationships amongst class, gender and ethnicity to reveal the negotiation of identity in late modernity. -

5. Calling for International Solidarity: Hanns Eisler’S Mass Songs in the Soviet Union

From Massenlieder to Massovaia Pesnia: Musical Exchanges between Communists and Socialists of Weimar Germany and the Early Soviet Union by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Bryan Gilliam, Supervisor ___________________________ Edna Andrews ___________________________ John Supko ___________________________ Jacqueline Waeber Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 i v ABSTRACT From Massenlieder to Massovaia Pesnia: Musical Exchanges between Communists and Socialists of Weimar Germany and the Early Soviet Union by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Bryan Gilliam, Supervisor ___________________________ Edna Andrews ___________________________ John Supko ___________________________ Jacqueline Waeber An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 Copyright by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry 2014 Abstract Group songs with direct political messages rose to enormous popularity during the interwar period (1918-1939), particularly in recently-defeated Germany and in the newly- established Soviet Union. This dissertation explores the musical relationship between these two troubled countries and aims to explain the similarities and differences in their approaches to collective singing. The discussion of the very complex and problematic relationship between the German left and the Soviet government sets the framework for the analysis of music. Beginning in late 1920s, as a result of Stalin’s abandonment of the international revolutionary cause, the divergences between the policies of the Soviet government and utopian aims of the German communist party can be traced in the musical propaganda of both countries. -

Bloomsbury Adult Catalog Fall 2020

BLOOMSBURY Fall 2020 September – December BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING SEPTEMBER 2020 The Apology Eve Ensler From the bestselling author of The Vagina Monologues—a powerful, life-changing examination of abuse and atonement. Like millions of women, Eve Ensler has been waiting much of her lifetime for an apology. Sexually and physically abused by her father, Eve has struggled her whole life from this betrayal, longing for an honest reckoning from a man who is long dead. After years of work as an anti-violence activist, she decided she would wait no longer; an apology could be imagined, by her, for her, to her. The Apology, written by Eve from her father’s point of view in the words she longed to hear, attempts to transform the abuse she suffered with unflinching truthfulness, compassion, and an expansive vision for the future. Through The Apology, Eve has set out to provide a new way for herself and a BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY possible road for others so that survivors of abuse may finally envision how to / LITERARY be free. She grapples with questions she has sought answers to since she first Bloomsbury Publishing | 9/15/2020 9781635575118 | $16.00 / $22.00 Can. realized the impact of her father’s abuse on her life: How do we offer a doorway Trade Paperback | 128 pages rather than a locked cell? How do we move from humiliation to revelation, from 8.3 in H | 5.5 in W curtailing behavior to changing it, from condemning perpetrators to calling Other Available Formats: them to reckoning? What will it take for abusers to genuinely apologize? Hardcover ISBN: 9781635574388 Remarkable and original, The Apology is an acutely transformational look at how, from the wounds of sexual abuse, we can begin to reemerge and heal. -

The Desert of Wheat

1 The Desert of Wheat The Desert of Wheat CHAPTER I<p> CHAPTER I CHAPTER I CHAPTER II<p> CHAPTER II CHAPTER II CHAPTER III<p> CHAPTER III CHAPTER III CHAPTER IV<p> CHAPTER IV CHAPTER IV CHAPTER V<p> CHAPTER V CHAPTER V CHAPTER VI<p> CHAPTER VI CHAPTER VI CHAPTER VII<p> CHAPTER VII CHAPTER VII CHAPTER VIII<p> CHAPTER VIII CHAPTER VIII CHAPTER IX<p> CHAPTER IX CHAPTER IX CHAPTER X<p> CHAPTER X CHAPTER X CHAPTER XI<p> CHAPTER XI CHAPTER XI CHAPTER XII<p> CHAPTER XII 2 CHAPTER XII CHAPTER XIII<p> CHAPTER XIII CHAPTER XIII CHAPTER XIV<p> CHAPTER XIV CHAPTER XIV CHAPTER XV<p> CHAPTER XV CHAPTER XV CHAPTER XVI<p> CHAPTER XVI CHAPTER XVI CHAPTER XVII<p> CHAPTER XVII CHAPTER XVII CHAPTER XVIII<p> CHAPTER XVIII CHAPTER XVIII CHAPTER XIX<p> CHAPTER XIX CHAPTER XIX CHAPTER XX<p> CHAPTER XX CHAPTER XX CHAPTER XXI<p> CHAPTER XXI CHAPTER XXI CHAPTER XXII<p> CHAPTER XXII CHAPTER XXII CHAPTER XXIII<p> CHAPTER XXIII CHAPTER XXIII CHAPTER XXIV<p> CHAPTER XXIV CHAPTER XXIV CHAPTER XXV<p> CHAPTER XXV CHAPTER XXV CHAPTER XXVI<p> CHAPTER XXVI CHAPTER XXVI CHAPTER XXVII<p> CHAPTER XXVII CHAPTER XXVII CHAPTER XXVIII<p> CHAPTER XXVIII CHAPTER XXVIII CHAPTER XXIX<p> CHAPTER XXIX CHAPTER XXIX The Desert of Wheat 3 CHAPTER XXX<p> CHAPTER XXX CHAPTER XXX CHAPTER XXXI<p> CHAPTER XXXI CHAPTER XXXI CHAPTER XXXII<p> CHAPTER XXXII CHAPTER XXXII The Desert of Wheat The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Desert of Wheat, by Zane Grey This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. -

The Faerie Queene Study Guide

The Faerie Queene Study Guide © 2018 eNotes.com, Inc. or its Licensors. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. Summary The Faerie Queene is a long epic poem that begins and ends with Christian affirmations. In it, Edmund Spenser draws on both Christian and classical themes, integrating the two traditions with references to contemporary politics and religion. The poem begins with a representation of holiness in book 1, and the Mutabilitie Cantos (first printed with the poem in 1609 after Spenser’s death) conclude with a prayer. Book 1 is identified as the Legend of the Knight of the Red Cross (or Saint George) in canto 2, verses 11-12. Red Cross, as an individual, is the Protestant Everyman, but as Saint George, historically England’s patron saint, he also represents the collective people of England. He is a pilgrim who hopes to achieve the virtue holiness, and for the reader his adventures illustrate the path to holiness. Red Cross’s overarching quest, as an individual, is to behold a vision of the New Jerusalem, but he also is engaged in a holy quest involving the lady Una, who represents the one true faith. To liberate Una’s parents, the king and queen, Adam and Eve, Red Cross must slay the dragon, who holds them prisoner. The dragon represents sin, the Spanish Armada, and the Beast of the Apocalypse, and when Red Cross defeats the dragon he is in effect restoring Eden. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2017 The Laws of Fantasy Remix Matthew J. Dauphin Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE LAWS OF FANTASY REMIX By MATTHEW J. DAUPHIN A Dissertation submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2017 Matthew J. Dauphin defended this dissertation on March 29, 2017. The members of the supervisory committee were: Barry Faulk Professor Directing Dissertation Donna Marie Nudd University Representative Trinyan Mariano Committee Member Christina Parker-Flynn Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To every teacher along my path who believed in me, encouraged me to reach for more, and withheld judgment when I failed, so I would not fear to try again. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................................................................ v 1. AN INTRODUCTION TO FANTASY REMIX ...................................................................... 1 Fantasy Remix as a Technique of Resistance, Subversion, and Conformity ......................... 9 Morality, Justice, and the Symbols of Law: Abstract -

CONTEMPORARY COLLECTION Bolero Music by Maurice Ravel Video Link Choreography by Anatoly Emelianov

The Crown of Russian Ballet CONTEMPORARY COLLECTION Bolero Music by Maurice Ravel Video Link Choreography by Anatoly Emelianov. 10-12 dancers The premiere took place on February 10, 2011 in Queretaro (Mexico) And we are born from one, and we are similar to each other, and at first there is no difference between us. But over time, between us their are features of a completely different, incomprehensible nature , which grows into mistrust and irritation, eventually becoming a confrontation that ends in death. And this can all happen again ... Video Link Carmen Music by Bizet – Shchedrin - 40 min. 12-16 dancers Carmen Music by Bizet – Shchedrin - 40 min. 12-16 dancers Video Link “Carmen” by Georges Bizet. For almost a century and a half the image of Carmen irresistibly attracts many artists who embody it in verse and prose, in music and theatre, in painting and cinema. For the first time the plot about the most famous and passionate gypsy became a fact-art in 1845, when the French writer Prosper Merimee wrote his novel. A year later the young choreographer Marius Petipa created a one-act ballet “Carmen and Toreador” on stage at the Madrid Theatre, 29 years later one of the most famous opera masterpieces - “Carmen” of Georges Bizet appears. Since then, the image of the Spanish gypsy is inextricably linked with the music of the great Frenchman. In the XX century ballets using the score of Bizet, appeared regularly. Among the most famous are Carmen by Roland Petit, created by him in 1949 for Zizi Jeanmaire, and a 1971 performance in Stuttgart by John Cranko where Marcia Heide danced. -

The Hero's Adventure

THEHERO'S ADVENTURE Fwtlwrmore,we hauenot evento risk theadcJenture alone, f- tln heroesof all time hnvegone before us. The labyrinth is tharoughlyknown. We have only to follow thethread of the lwro path,and, wllere we had thoughtto find an abomination, we slwllfirrd a god, And wherewe had thoughtto slay another, we shall slay owselvel Where we had thoughtto trauel outwmd,we will cometo thecenter of our own existence.And wlvre we had thoughtrc be alone,we will be withall the twrW. -JosrrH CRNapsrLL MoYERS:\DUhy are there so many storiesof the hero in mythologyl cAMPBELL,Because that's what'sworth writing about. Evenin popular rcls, the main character is a hero or heroine rho h"r found or iorr" beyondthe normal rangeof achievementand experience.A hero who hasgiven his or her life to somethingbigger than oneself. YERS:soin all of thesecultures, whatever the localcostumethe hero be wearing,what is the deed? MPBELL:well, there are rwo typesof deed.one is the physicaldeed, ich the hero performsa courageousact in battle or saves'alife. The kind is the spiritual deed, in which the hero leams to experiencethe prmal range of human spiritual life and rhen comes 6ack with a FACING PAGE: usualhero adventurebegins with someone from whom something Martin L. King, Jr., r taken, or who feels there's something lacking in the .ro*"'i 1963. availableor permittedto the membersof his soCiety.This person off on a seriesof adventuresbeyond the ordinary, Alwo is sonvonewlwhas either to giwn hisarlwkfe what hasbeen lost or n to discoversome life-giving elixir. It's usually somethingbigger tlwn a goingand a retuming. -

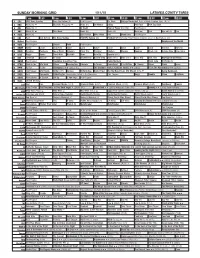

Sunday Morning Grid 1/11/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/11/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Dr. Chris College Basketball Duke at North Carolina State. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) On Money Skiing PGA Tour PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football NFC Divisional Playoff Dallas Cowboys at Green Bay Packers. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Employee of the Month 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Revenge of the Nerds 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Pablo Montero Hotel Todo Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

Docs for Sale Shortlist Films A-Z Docs for Sale 22Nd International Documentary Market Amsterdam Docs for Sale 22Nd International Documentary Market Amsterdam

523 films Shortlisted by alphabet Docs for Sale Shortlist Films A-Z nd International Documentary Market Amsterdam nd International Documentary Market Amsterdam Docs for Sale 22 Docs for Sale 22 Human Interest / Social Issues Art / Music / Culture Human Interest / Social Issues 14 Cases Adieu à G. A Documentary on An Almost Impossible Friendship Marianna Kaat, Estonia, 85’, p.6 the Dutch Artist Ger van Elk – Rabbi, Priester and Imam Film follows different age present- Djoeke Veeninga, Marlou van den Berge, Peter Beringer, Austria, 46’, p.22 day Estonian Russians who are facing Jeroen Visser, The Netherlands, 64’, p.14 The documentary followed the three men difficulties with their identities. The film Adieu à G… follows the artist from Austria to the Holy Land, where together Baltic Film Production – Marianna Kaat – [email protected] towards the end of his life, when in Venice he they visited the most significant places of Youth performed a Replacement Piece and designed pilgrimage for their religions and discussed the 17 his last work: 12 Automatic Landscapes. similarities and differences between them. At the same time, the films zigzags through ORF - Enterprise – Armin Luttenberger Widad Shafakoj, Jordan, United Kingdom, 74’, p.7 his whole oeuvre and Ger van Elk talks – [email protected] The Jordanian under-17 women’s football about his ideas and how he put them team embarks to compete in the FIFA U17 Politics / Society into practice. Adieu à G… allows us to look Women’s World Cup Jordan 2016 - in a sport beyond the horizon, at what we don’t see. -

Ideology and Pedagogical Practices of Literacy Teaching in the First Grade of Israeli Primary Schools - an Ethnographic Study

THE CHILDREN OF THE BOOK. Ideology and Pedagogical Practices of Literacy Teaching in the First Grade of Israeli Primary Schools - An Ethnographic Study liana Zailer THESIS SUBMITTED FOR the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY University of London, Institute of Education August 1992 ABSTRACT In this thesis it is argued that, beneath the surface modernity of literacy education in Israel, lie age-old mechanisms that are being used to instil into young readers an unquestioning adherence to the voice of a single cultural text. Children in the modern Israeli State are the latest heirs of an ancient religio-cultural tradition. Throughout its 'longue duree', the Jewish community has sought its identity and striven for continued existence by dedication to ideals of literacy and to a single Text. A review of the whole course of Jewish history which focuses on the role of literacy reveals that this is the case. Close inspection of the approach of the contemporary Israeli State to the teaching of literacy in primary schools shows that these ancient imperatives are still present and active, albeit in transformed ways. The ideology of the Israeli State, embodied in its 'Discourse of Nation-Building' shapes and moves the centralised school-system and its pedagogy. The main themes of the 'discourse' - solidarity, cohesion and defence - lie beneath the apparently neutral surface of standard reading-scheme texts. During the first hours of learning to read in school, the Israeli child is also being invited to set out on the road to being a soldier. An ethnographic study of what actually takes place when literacy is being taught in Israeli first grades establishes that, for the young Israeli, the first encounter with school literacy is a moment in her personal and social life when she is initiated both into the ancient Text and into the modern national/political discourse.