On Modernity, Identity and White-Collar Boxing. Phd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jarndyce Catalogue 224.Pdf

Jarndyce Antiquarian Booksellers 46, Great Russell Street Telephone: 020 7631 4220 (opp. British Museum) Fax: 020 7631 1882 Bloomsbury, Email: [email protected] London www.jarndyce.co.uk WC1B 3PA VAT.No.: GB 524 0890 57 CATALOGUE CCXXIV SUMMER 2017 A SUMMER MISCELLANY Catalogue & Production: Ed Lake & Carol Murphy. All items are London-published and in at least good condition, unless otherwise stated. Prices are nett. Items marked with a dagger (†) incur VAT (20%) to customers within the EU. A charge for postage and insurance will be added to the invoice total. We accept payment by VISA or MASTERCARD. If payment is made by US cheque, please add $25.00 towards the costs of conversion. High resolution images are available for all items, on request; please email: [email protected]. JARNDYCE CATALOGUES CURRENTLY AVAILABLE include (price £10.00 each unless otherwise stated): The Museum: A Jarndyce Miscellany; European Literature in Translation; Bloods & Penny Dreadfuls; The Dickens Catalogue; Conduct & Education (£5); The Romantics: A-Z with The Romantic Background (four catalogues, £20); JARNDYCE CATALOGUES IN PREPARATION include: Books & Pamphlets 1641-1825, with a Supplement of 18th Century Verse; Sex, Drugs & Popular Medicine; 19th Century Novels; Women Writers; English Language; Plays. PLEASE REMEMBER: If you have books to sell, please get in touch with Brian Lake at Jarndyce. Valuations for insurance or probate can be undertaken anywhere, by arrangement. A SUBSCRIPTION SERVICE is available for Jarndyce Catalogues for those who do not regularly purchase. Please send £30.00 (£60.00 overseas) for four issues, specifying the catalogues you would like to receive. -

The Abysmal Brute, by Jack London

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Abysmal Brute, by Jack London This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Abysmal Brute Author: Jack London Illustrator: Gordon Grant Release Date: November 12, 2017 [EBook #55948] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ABYSMAL BRUTE *** Produced by Jeroen Hellingman and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net/ for Project Gutenberg (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.) THE ABYSMAL BRUTE Original Frontispiece. Original Title Page. THE ABYSMAL BRUTE BY JACK LONDON Author of “The Call of the Wild,” “The Sea Wolf,” “Smoke Bellew,” “The Night Born,” etc. NEW YORK THE CENTURY CO. 1913 Copyright, 1913, by THE CENTURY CO. Copyright, 1911, by STREET & SMITH. New York Published, May, 1913 THE ABYSMAL BRUTE I Sam Stubener ran through his mail carelessly and rapidly. As became a manager of prize-fighters, he was accustomed to a various and bizarre correspondence. Every crank, sport, near sport, and reformer seemed to have ideas to impart to him. From dire threats against his life to milder threats, such as pushing in the front of his face, from rabbit-foot fetishes to lucky horse-shoes, from dinky jerkwater bids to the quarter-of-a-million-dollar offers of irresponsible nobodies, he knew the whole run of the surprise portion of his mail. -

HEAVYWEIGHT (OVER 200 LBS) CH Carlos Takam FRA 1 Derek Chisora ZWE 2 Agit Kabayel GER 3 Bogdan Dinu ROU 4 Adrian Granat SWE 5 Mi

HEAVYWEIGHT (OVER 200 LBS) CRUISERWEIGHT (200 LBS) LT. HEAVYWEIGHT (175 LBS) S. MIDDLEWEIGHT (168 LBS) CH Carlos Takam FRA CH Krzysztof Wlodarczyk POL CH VACANT CH Vincent Feigenbutz GER 1 Derek Chisora ZWE 1 Maxim Maslov RUS 1 Medhi Amar FRA 1 Roamer Angulo COL 2 Agit Kabayel GER 2 Craig Kennedy WLS 2 Umar Salamov UKR 2 Robin Krasniqi SRB 3 Bogdan Dinu ROU 3 Ryad Merhy BEL 3 Dariusz Sek POL 3 Mariano Hilario ESP 4 Adrian Granat SWE 4 Ismayl Syllakh UKR 4 Karo Murat GER 4 Ronald Gavril USA 5 Michael Wallisch GER 5 Imre Szello HUN 5 Hugo Kasperski FRA 5 Dominik Britsch GER 6 Otto Wallin SWE 6 Matty Askin ENG 6 Dmitrii Bivol KGZ 6 Jamie Cox ENG 7 Zhang Zhilei CHN 7 Enad Licina GER 7 Meng Fanlong CHN 7 Rohan Murdock AUS 8 Krzysztof Zimnoch POL 8 Issa Akberbayev KAZ 8 Egor Mekhontsev RUS 8 Yovany Lorenzo DOM 9 Edmund Gerber GER 9 NOT RATED 9 Frank Buglioni ENG 9 Francy Ntetu COD 10 Herve Hubeaux BEL 10 Olanrewasu Durodola NGA 10 Shefat Isufi SRB 10 Przemyslaw Opalach POL 11 Oscar Rivas CAN 11 Taylor Mabika GAB 11 Samy Enbom FIN 11 Dilmurod Satybaldiev KGZ 12 Tom Schwarz GER 12 Agron Dzila CHE 12 Hakim Zoulikha FRA 12 Juergen Doberstein KAZ 13 Odlanier Solis CUB 13 Roberto Bolonti ARG 13 Norbert Nemesapati HUN 13 Christopher Rebrasse FRA 14 Sergey Kuzmin RUS 14 Yves Ngabu BEL 14 Serdar Sahin GER 14 Luke Blackledge ENG 15 Franz Rill GER 15 Leon Harth GER 15 Bilal Laggoune BEL 15 Tim Robin Lihaug NOR Page 1/4 MIDDLEWEIGHT (160 LBS) JR. -

The Safety of BKB in a Modern Age

The Safety of BKB in a modern age Stu Armstrong 1 | Page The Safety of Bare Knuckle Boxing in a modern age Copyright Stu Armstrong 2015© www.stuarmstrong.com Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 3 The Author .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Why write this paper? ......................................................................................................................... 3 The Safety of BKB in a modern age ................................................................................................... 3 Pugilistic Dementia ............................................................................................................................. 4 The Marquis of Queensbury Rules’ (1867) ......................................................................................... 4 The London Prize Ring Rules (1743) ................................................................................................. 5 Summary ............................................................................................................................................. 7 Bibliography ........................................................................................................................................ 8 2 | Page The Safety of Bare Knuckle Boxing in a modern age Copyright Stu Armstrong 2015© -

Human Dignity Issues in the Sports Business Industry

DEVELOPING RESPONSIBLE CONTRIBUTORS | Human Dignity Issues in the Sports Business Industry Matt Garrett is the chair of the Division of Physical Education and Sport Studies and coordinator of the Sport Management Program at Loras College. His success in the sport industry includes three national championships in sport management case study tournaments, NCAA Division III tournament appearances as a women’s basketball and softball coach, and multiple youth baseball championships. Developing Responsible Contributors draws on these experiences, as well as plenty of failures, to explore a host of issues tied to human dignity in the sport business industry. These include encounters with hazing and other forms of violence in sport, inappropriate pressures on young athletes, and the exploitation of college athletes and women in the sport business industry. Garrett is the author of Preparing the Successful Coach and Matt Garrett Timeless: Recollections of Family and America’s Pastime. He lives in Dubuque with his wife and three children. | Human Dignity Issues in the LORAS COLLEGE PRESS Sports Business Industry Matt Garrett PRESS i Developing Responsible Contributors: Human Dignity Issues in the Sport Business Industry Matthew Garrett, Ph.D. Professor of Physical Education and Sports Studies Loras College Loras College Press Dubuque, Iowa ii Volume 5 in the Frank and Ida Goedken Series Published with Funds provided by The Archbishop Kucera Center for Catholic Intellectual and Spiritual Life at Loras College. Published by the Loras College Press (Dubuque, Iowa), David Carroll Cochran, Director. Publication preparation by Helen Kennedy, Marketing Department, Loras College. Cover Design by Mary Kay Mueller, Marketing Department, Loras College. -

China Wanning Cup 2014 Wku - World Championships 29

CHINA WANNING CUP 2014 WKU - WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS 29. OCTOBER – 02. NOVEMBER 2014 PROGRAM – MEDIA - SPONSORING PROGRAM MEDIA SPONSORING CHINA WANNING CUP 2014 WKU - WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS 12. – 18. AUGUST 2014 02 Dear members, friends and partners of WKU, All athletes will find perfect and professional Dear all, conditions at Wanning to perform great moments of combat sports. Welcome to CHINA WANNING CUP 2014 WKU CHINA WANNING CUP 2014 WKU - WORLD - WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS at the beautiful CHAMPIONSHIPS is the global tournament of tropical island of Hainan at the south coast of national teams in the disciplines of Free Style China. Forms, MMA, Thai Boxing, Pointfighting & Light Contact within selected weight classes. The success story of modern combat sports started in China! Chinese martial arts THE CHAMPIONS CLUB! the Mixed Pro World originated during the Xia Dynasty more than Championship Fight Night will be another 4000 years ago. It is said the Yellow Emperor highlight. The strongest men and women of Huangdi (legendary date of ascension 2698 BC) professional martial arts will challenge the introduced the earliest fighting systems to finest fighters from China. China. We are looking forward to see you in Wanning It was very logic and consequent to me, to between 29. October. – 02. November 2014. organize WKU - World Championships in China one day. I always wanted to give fighters from Klaus Nonnemacher all over the world, the opportunity to compete World President GCO/WKU at this holly ground of martial arts. With my experience and passion for organizing combat sports World Championships for more than 15 years, I make sure, this will be a new chapter in the history book of WKU. -

Boxing Lessons Download Apple App Boxing Lessons Download Apple App

boxing lessons download apple app Boxing lessons download apple app. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67d94de379b815dc • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Best boxing training apps for Android and iOS. Boxing is one of the most popular sports. If you’ve purchased a punching bag recently or you’re a wannabe boxer, you can learn the sport of boxing from the comfort of your home without spending a dime with the following applications: Best boxing training apps for Android and iOS Kickboxing Fitness Trainer Boxhitt – Boxing / Kickboxing workouts and more Boxtastic: Bag / Shadow Boxing Home HIIT Workouts Boxing Trainer Boxing Round Interval Timer Boxing Training – Offline Videos. Best boxing training apps for Android and iOS. Kickboxing Fitness Trainer. This application teaches kickboxing to its users for free by making them go through various challenges. The challenges are designed for amateur as well as experienced boxers. -

This Is a Terrific Book from a True Boxing Man and the Best Account of the Making of a Boxing Legend.” Glenn Mccrory, Sky Sports

“This is a terrific book from a true boxing man and the best account of the making of a boxing legend.” Glenn McCrory, Sky Sports Contents About the author 8 Acknowledgements 9 Foreword 11 Introduction 13 Fight No 1 Emanuele Leo 47 Fight No 2 Paul Butlin 55 Fight No 3 Hrvoje Kisicek 6 3 Fight No 4 Dorian Darch 71 Fight No 5 Hector Avila 77 Fight No 6 Matt Legg 8 5 Fight No 7 Matt Skelton 93 Fight No 8 Konstantin Airich 101 Fight No 9 Denis Bakhtov 10 7 Fight No 10 Michael Sprott 113 Fight No 11 Jason Gavern 11 9 Fight No 12 Raphael Zumbano Love 12 7 Fight No 13 Kevin Johnson 13 3 Fight No 14 Gary Cornish 1 41 Fight No 15 Dillian Whyte 149 Fight No 16 Charles Martin 15 9 Fight No 17 Dominic Breazeale 16 9 Fight No 18 Eric Molina 17 7 Fight No 19 Wladimir Klitschko 185 Fight No 20 Carlos Takam 201 Anthony Joshua Professional Record 215 Index 21 9 Introduction GROWING UP, boxing didn’t interest ‘Femi’. ‘Never watched it,’ said Anthony Oluwafemi Olaseni Joshua, to give him his full name He was too busy climbing things! ‘As a child, I used to get bored a lot,’ Joshua told Sky Sports ‘I remember being bored, always out I’m a real street kid I like to be out exploring, that’s my type of thing Sitting at home on the computer isn’t really what I was brought up doing I was really active, climbing trees, poles and in the woods ’ He also ran fast Joshua reportedly ran 100 metres in 11 seconds when he was 14 years old, had a few training sessions at Callowland Amateur Boxing Club and scored lots of goals on the football pitch One season, he scored -

Cambridge University Amateur Boxing Club Code of Conduct

Cambridge University Amateur Boxing Club Code of Conduct INTRODUCTION Cambridge University Amateur Boxing Club ("CUABC") is fully committed to safeguarding and promoting the well being of all its members to ensure a positive and enjoyable experience. All those involved in CUABC activities, whether they are involved as participants, coaches, officials or spectators, are therefore required to adhere to the standards of behaviour – set out within this Code of Conduct - and to support the mission of the CUABC. This Code of Conduct has been developed to ensure the highest possible standards of competition and sportsmanship as well as promoting fairness, honesty and positive behaviour in relation to the conduct of all those representing CUABC. OUR COMMITMENT CUABC respect the rights, dignity and worth of every person involved in its activities. CUABC is committed to its members enjoying boxing in an environment free from discrimination, intimidation, harassment and abuse. CUABC believes that it is the responsibility of all of all its members to challenge discriminatory behaviour and promote equality of opportunity. AFFILIATIONS CUABC is governed by its constitution in line with England Boxing, and is registered with the University of Cambridge Sports Service. This Code of Conduct is in addition, and by no means replaces, the standards set by England Boxing, the student’s individual college and the overarching Proctor regulations. CUABC is also affiliated to England Boxing and abides by their regulations regarding their respective competitions. -

Boxing Edition

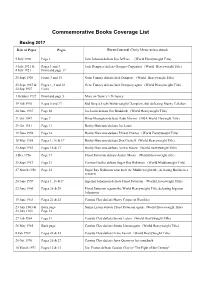

Commemorative Books Coverage List Boxing 2017 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 5 July 1910 Page 3 Jack Johnson defeats Jim Jeffries (World Heavyweight Title) 3 July 1921 & Pages 1 and 3 Jack Dempsey defeats Georges Carpentier (World Heavyweight Title) 4 July 1921 Front and page 17 25 Sept 1926 Front, 3 and 15 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1927 & Pages 1, 3 and 18 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey again (World Heavyweight Title) 24 Sep 1927 Front 1 October 1927 Front and page 5 More on Tunney v Dempsey 19 Feb 1930 Pages 5 and 22 Kid Berg is Light Welterweight Champion after defeating Mushy Callahan 24 June 1937 Page 30 Joe Louis defeats Jim Braddock (World Heavyweight Title) 21 Oct 1947 Page 7 Rinty Monaghan defeats Dado Marino (NBA World Flyweight Title) 29 Oct 1951 Page 11 Rocky Marciano defeats Joe Louis 19 June 1954 Page 14 Rocky Marciano defeats Ezzard Charles (World Heavyweight Title) 18 May 1955 Pages 1, 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Don Cockell (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1955 Pages 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight Title) 3 Dec 1956 Page 17 Floyd Patterson defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight title) 25 Sept 1957 Page 23 Carmen Basilio defeats Sugar Ray Robinson (World Middleweight Title) 27 March 1958 Page 23 Sugar Ray Robinson wins back the Middleweight title, defeating Basilio in a rematch 28 June 1959 Pages 1, 16 &17 Ingemar Johansson defeats Floyd Patterson (World Heavyweight Title) 22 June 1960 Pages 28 & 29 Floyd Patterson -

No Heavyweight Rumor: Ruiz-Arreola, Parker-Chisora Are

No Heavyweight Rumor: Ruiz- Arreola, Parker-Chisora are for real By Norm Frauenheim- The heavyweight division, once revered, has been reduced to a rumor. Only Tyson Fury-Anthony Joshua seems to matter, despite mounting doubts about reported negotiations full of promises and short on specifics. Joshua promoter Eddie Hearn says it will happen this summer. Fury co-promoter Frank Warren says it won’t. That’s where it started months ago. That’s where it still is, although there’s a growing chorus of frustration from Fury and his American promoter Bob Arum, whose skepticism about a $150 million offer from Saudi Arabia was evident in multiple media reports this week. A deal hinges on whether the money is really there. A deal – date and place – has yet to be announced, hence deepening suspicions that the offer is bupkis, just more dust in a Haboob. Meanwhile, Fury has taken to social media and Hearn is his target. Fury, whose trash talk is as deadly as his jab, is ripping Hearn, saying that the UK promoter has cozied up to Canelo Alvarez in the Mexican’s title fight against UK super- middleweight Billy Joe Saunders on May 8 in Arlington, Tex. For the May fight, at least, Hearn is the promoter of record for both. But Fury is questioning his allegiances, which means Hearn is probably as popular as a piñata back home in Britain. Such is that state of the heavyweights, a flagship as rudderless as ever. Yet, chaos at the top hasn’t silenced it. Andy Ruiz Jr. and Chris Arreola, Joe Parker and Derek Chisora will do what Fury and Joshua may — may not — do. -

A Situational Analysis of Boxing. International Journal of Sport and Society, 11 (1)

Fulton, John (2019) A Situational Analysis of Boxing. International Journal of Sport and Society, 11 (1). pp. 24-42. ISSN 2152-7857 Downloaded from: http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/id/eprint/11386/ Usage guidelines Please refer to the usage guidelines at http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. VOLUME 11 ISSUE 1 The International Journal of Sport and Society _________________________________________________________________________ Downloaded on Thu Oct 31 2019 at 08:42:47 UTC A Situational Analysis of Boxing JOHN FULTON SPORTANDSOCIETY.COM EDITOR Dr. Jörg Krieger, Aarhus University, Denmark ACTING DIRECTOR OF PUBLISHING Jeremy Boehme, Common Ground Research Networks, USA MANAGING EDITOR Helen Repp, Common Ground Research Networks, USA ADVISORY BOARD The Sport & Society Research Network recognizes the contribution of many in the evolution of the Research Network. The principal role of the Advisory Board has been, and is, to drive the overall intellectual direction of the Research Network. A full list of members can be found at https://sportandsociety.com/about/advisory-board. PEER REVIEW Articles published in The International Journal of Sport and Society re peer reviewed using a two-way anonymous peer review model. Reviewers are active participants of the Sport & Society Research Network or a thematically related Research Network. The publisher, editors, reviewers, and authors all agree upon the following standards of expected ethical behavior, which are based on the Committee on THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF Publication Ethics (COPE) Core Practices. More information can be SPORT AND SOCIETY found at: https://sportandsociety.com/journal/model. https://sportandsociety.com ISSN: 2152-7857 (Print) ARTICLE SUBMISSION ISSN: 2152-7865 (Online) The International Journal of Sport and Society publishes quarterly https://doi.org/10.18848/2152-7857/CGP (Journal) (March, June, September, December).