From Rookie to Rocky? on Modernity, Identity and White-Collar Boxing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jarndyce Catalogue 224.Pdf

Jarndyce Antiquarian Booksellers 46, Great Russell Street Telephone: 020 7631 4220 (opp. British Museum) Fax: 020 7631 1882 Bloomsbury, Email: [email protected] London www.jarndyce.co.uk WC1B 3PA VAT.No.: GB 524 0890 57 CATALOGUE CCXXIV SUMMER 2017 A SUMMER MISCELLANY Catalogue & Production: Ed Lake & Carol Murphy. All items are London-published and in at least good condition, unless otherwise stated. Prices are nett. Items marked with a dagger (†) incur VAT (20%) to customers within the EU. A charge for postage and insurance will be added to the invoice total. We accept payment by VISA or MASTERCARD. If payment is made by US cheque, please add $25.00 towards the costs of conversion. High resolution images are available for all items, on request; please email: [email protected]. JARNDYCE CATALOGUES CURRENTLY AVAILABLE include (price £10.00 each unless otherwise stated): The Museum: A Jarndyce Miscellany; European Literature in Translation; Bloods & Penny Dreadfuls; The Dickens Catalogue; Conduct & Education (£5); The Romantics: A-Z with The Romantic Background (four catalogues, £20); JARNDYCE CATALOGUES IN PREPARATION include: Books & Pamphlets 1641-1825, with a Supplement of 18th Century Verse; Sex, Drugs & Popular Medicine; 19th Century Novels; Women Writers; English Language; Plays. PLEASE REMEMBER: If you have books to sell, please get in touch with Brian Lake at Jarndyce. Valuations for insurance or probate can be undertaken anywhere, by arrangement. A SUBSCRIPTION SERVICE is available for Jarndyce Catalogues for those who do not regularly purchase. Please send £30.00 (£60.00 overseas) for four issues, specifying the catalogues you would like to receive. -

The Abysmal Brute, by Jack London

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Abysmal Brute, by Jack London This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Abysmal Brute Author: Jack London Illustrator: Gordon Grant Release Date: November 12, 2017 [EBook #55948] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ABYSMAL BRUTE *** Produced by Jeroen Hellingman and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net/ for Project Gutenberg (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.) THE ABYSMAL BRUTE Original Frontispiece. Original Title Page. THE ABYSMAL BRUTE BY JACK LONDON Author of “The Call of the Wild,” “The Sea Wolf,” “Smoke Bellew,” “The Night Born,” etc. NEW YORK THE CENTURY CO. 1913 Copyright, 1913, by THE CENTURY CO. Copyright, 1911, by STREET & SMITH. New York Published, May, 1913 THE ABYSMAL BRUTE I Sam Stubener ran through his mail carelessly and rapidly. As became a manager of prize-fighters, he was accustomed to a various and bizarre correspondence. Every crank, sport, near sport, and reformer seemed to have ideas to impart to him. From dire threats against his life to milder threats, such as pushing in the front of his face, from rabbit-foot fetishes to lucky horse-shoes, from dinky jerkwater bids to the quarter-of-a-million-dollar offers of irresponsible nobodies, he knew the whole run of the surprise portion of his mail. -

Rules Shooto

Rules Shooto tournaments are held under a strict and comprehensive set of rules. Its objectives are to protect the athlete and to ensure dynamic and fair fights. A distinction is made between amateur (Class C), semi-pro (Class B) and professional (Class A) rules. Depending on the class, certain techniques are prohibited and the fight duration is adapted as well. The different classes in Shooto make it possible for athletes to improve in a controlled and safe environment. Weight classes Featherweight – 60kg Lightweight – 65kg Welterweight – 70kg Middleweight – 76kg Light-Heavyweight – 83kg Cruiserweight – 91kg Heavyweight – +91kg Rules – Brief Version — A pro fight consists of three 5-minute rounds with one-minute breaks in between. Amateurs fight two 3-minute rounds, semi-pros fight two 5-minute rounds. — A referee oversees the fight in the ring and controls adherence of the rules. — Three judges score the fight according to effective strikes, takedowns and aggressivity/activity whilst standing and dominant positions, submission attempts and defense whilst being on the floor. — A victory can be scored by judges decision, knock-out (KO), technical knock-out (TKO), by submission or by referee- or doctor-stoppage. — Fighters are divided by weight classes. — Before the fight, fighters have to attend a medical check and the doctor needs to approve the fight. — Protective equipment (gloves, cup, mouthguard) are mandatory. Amateurs (C-class) are allowed to fight with headgear and shinguards. — Illegal fouls are headbutts, elbow-strikes, biting, groin attacks of any kind, attacks on the back or the back of the head, attacks on small joints, attacks on the eyes or ears and further actions which oppose a fair fight. -

HEAVYWEIGHT (OVER 200 LBS) CH Carlos Takam FRA 1 Derek Chisora ZWE 2 Agit Kabayel GER 3 Bogdan Dinu ROU 4 Adrian Granat SWE 5 Mi

HEAVYWEIGHT (OVER 200 LBS) CRUISERWEIGHT (200 LBS) LT. HEAVYWEIGHT (175 LBS) S. MIDDLEWEIGHT (168 LBS) CH Carlos Takam FRA CH Krzysztof Wlodarczyk POL CH VACANT CH Vincent Feigenbutz GER 1 Derek Chisora ZWE 1 Maxim Maslov RUS 1 Medhi Amar FRA 1 Roamer Angulo COL 2 Agit Kabayel GER 2 Craig Kennedy WLS 2 Umar Salamov UKR 2 Robin Krasniqi SRB 3 Bogdan Dinu ROU 3 Ryad Merhy BEL 3 Dariusz Sek POL 3 Mariano Hilario ESP 4 Adrian Granat SWE 4 Ismayl Syllakh UKR 4 Karo Murat GER 4 Ronald Gavril USA 5 Michael Wallisch GER 5 Imre Szello HUN 5 Hugo Kasperski FRA 5 Dominik Britsch GER 6 Otto Wallin SWE 6 Matty Askin ENG 6 Dmitrii Bivol KGZ 6 Jamie Cox ENG 7 Zhang Zhilei CHN 7 Enad Licina GER 7 Meng Fanlong CHN 7 Rohan Murdock AUS 8 Krzysztof Zimnoch POL 8 Issa Akberbayev KAZ 8 Egor Mekhontsev RUS 8 Yovany Lorenzo DOM 9 Edmund Gerber GER 9 NOT RATED 9 Frank Buglioni ENG 9 Francy Ntetu COD 10 Herve Hubeaux BEL 10 Olanrewasu Durodola NGA 10 Shefat Isufi SRB 10 Przemyslaw Opalach POL 11 Oscar Rivas CAN 11 Taylor Mabika GAB 11 Samy Enbom FIN 11 Dilmurod Satybaldiev KGZ 12 Tom Schwarz GER 12 Agron Dzila CHE 12 Hakim Zoulikha FRA 12 Juergen Doberstein KAZ 13 Odlanier Solis CUB 13 Roberto Bolonti ARG 13 Norbert Nemesapati HUN 13 Christopher Rebrasse FRA 14 Sergey Kuzmin RUS 14 Yves Ngabu BEL 14 Serdar Sahin GER 14 Luke Blackledge ENG 15 Franz Rill GER 15 Leon Harth GER 15 Bilal Laggoune BEL 15 Tim Robin Lihaug NOR Page 1/4 MIDDLEWEIGHT (160 LBS) JR. -

Behind the Mask: My Autobiography

Contents 1. List of Illustrations 2. Prologue 3. Introduction 4. 1 King for a Day 5. 2 Destiny’s Child 6. 3 Paris 7. 4 Vested Interests 8. 5 School of Hard Knocks 9. 6 Rolling with the Punches 10. 7 Finding Klitschko 11. 8 The Dark 12. 9 Into the Light 13. 10 Fat Chance 14. 11 Wild Ambition 15. 12 Drawing Power 16. 13 Family Values 17. 14 A New Dawn 18. 15 Bigger than Boxing 19. Illustrations 20. Useful Mental Health Contacts 21. Professional Boxing Record 22. Index About the Author Tyson Fury is the undefeated lineal heavyweight champion of the world. Born and raised in Manchester, Fury weighed just 1lb at birth after being born three months premature. His father John named him after Mike Tyson. From Irish traveller heritage, the“Gypsy King” is undefeated in 28 professional fights, winning 27 with 19 knockouts, and drawing once. His most famous victory came in 2015, when he stunned longtime champion Wladimir Klitschko to win the WBA, IBF and WBO world heavyweight titles. He was forced to vacate the belts because of issues with drugs, alcohol and mental health, and did not fight again for more than two years. Most thought he was done with boxing forever. Until an amazing comeback fight with Deontay Wilder in December 2018. It was an instant classic, ending in a split decision tie. Outside of the ring, Tyson Fury is a mental health ambassador. He donated his million dollar purse from the Deontay Wilder fight to the homeless. This book is dedicated to the cause of mental health awareness. -

Fighters and Fathers: Managing Masculinity in Contemporary Boxing Cinema

Fighters and Fathers: Managing Masculinity in Contemporary Boxing Cinema JOSH SOPIARZ In Antoine Fuqua’s film Southpaw (2015), just as Jake Gyllenhaal’s character Billy Hope attempts suicide by crashing his luxury sedan into a tree in the front yard, his ten-year-old daughter, Leila, sends him a text message asking: “Daddy. Where are you?” (00:46:04). Her answer comes seconds later when, upon hearing a crash, she finds her father in a heap concussed and bleeding badly on the white marble floor of their home’s entryway. Upon waking, Billy’s first and only concern is Leila. Hospital workers, in an effort to calm him, tell Billy that Leila is safe “with child services” (00:48:08-00:48:10) This news does not comfort Billy. Instead, upon learning that Leila is in the state’s custody, the former light heavyweight champion of the world, with face bloodied and muscles rippling, makes his most concerted effort to get up and leave—presumably, to find his daughter. Before he can rise, however, a doctor administers a large dose of sedative and the heretofore unrestrainable Billy fades into unconsciousness as the scene ends. Leila’s simple question—“Daddy. Where are you?”—is central not only to Southpaw but is also relevant for most major boxing films of the 21st century.1 This includes Clint Eastwood’s Million Dollar Baby (2004), David O. Russell’s The Fighter (2010), Ryan Coogler’s Creed (2015), Jonathan Jakubowic’s Hands of Stone (2016), and Stephen Caple, Jr.’s Creed II (2018). These films establish fighter/trainer relationships as alternatives to otherwise biological or “traditional” father/son relationships. -

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS of OCTOBER 2005 Created on November 04Rd, 2005 MEMBERS CHAIRMAN P.O

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS OF OCTOBER 2005 Created on November 04rd, 2005 MEMBERS CHAIRMAN P.O. BOX 377 JOSE OLIVER GOMEZ E-mail: [email protected] JOSE EMILIO GRAGLIA (ARGENTINA) MARACAY 2101 -A ALAN KIM (KOREA) EDO. ARAGUA - VENEZUELA SHIGERU KOJIMA (JAPAN) PHONE: + (58-244) 663-1584 VICE CHAIRMAN GONZALO LOPEZ SILVERO (USA) + (58-244) 663-3347 GEORGE MARTINEZ E-mail: [email protected] MEDIA ADVISORS FAX: + (58-244) 663-3177 E-mail: [email protected] SEBASTIAN CONTURSI (ARGENTINA) Web site: www.wbaonline.com UNIFIED CHAMPION: JEAN MARC MORMECK FRA World Champion: JOHN RUIZ USA Won Title: 04-02-05 World Champion: FABRICE TIOZZO FRA Won Title: 12-13 -03 Last Defense: Won Title: 03-20- 04 Last Mandatory: 04-30 -05 _________________________________ Last Mandatory: 02-26- 05 Last Defense: 04-30 -05 World C hampion: VACANT Last Defense: 02-26- 05 WBC: VITALI KLITSCHKO - IBF: CHRIS BYRD WBC: JEAN MARC MORMECK- IBF: O’NEIL BELL WBC: THOMAS ADAMEK - IBF: CLINTON WOODS WBO : LAMON BREWSTER WBO : JOHNNY NELSON WBO : ZSOLT ERDEI 1. NICOLAY VALUEV (OC) RUS 1. VALERY BRUDOV RUS 1. JORGE CASTRO (LAC) ARG 2. NOT RATED 2. VIRGIL HILL USA 2. SILVIO BRANCO (OC) ITA 3. WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO UKR 200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) 3. GUILLERMO JONES (0C) PAN 3. MANNY SIACA (LAC-INTERIM) P.R. ( Over 200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) 4. RAY AUSTIN (LAC) USA 4. STEVE CUNNINGHAM USA (175 Lbs / 79.38 Kgs) 4. GLEN JOHNSON USA ( 5. CALVIN BROCK USA 5. LUIS PINEDA (LAC) PAN 5. PIETRO AURINO ITA l 6. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 4, 2020 [email protected] PANCRASE 316, July 24, 2020 – Studio Coast, Tokyo Bout Hype A

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 4, 2020 PANCRASE 316, July 24, 2020 – Studio Coast, Tokyo Bout Hype After a five-month hiatus, the legendary promotion Pancrase sets off the summer fireworks with a stellar mixed martial card. Studio Coast plays host to 8 main card bouts, 3 preliminary match ups, and 12 bouts in the continuation of the 2020 Neo Blood Tournament heats on July 24th in the first event since February. Reigning Featherweight King of Pancrase Champion, Isao Kobayashi headlines the main event in a non-title bout against Akira Okada who drops down from Featherweight to meet him. The Never Quit gym ace and Bellator veteran, Kobayashi is a former Pancrase Lightweight Champion. The ripped and powerful Okada has a tough welcome to the Featherweight division, but possesses notoriously frightening physical power. “Isao” the reigning Featherweight King of Pancrase Champion, has been unstoppable in nearly three years. He claimed the interim title by way of disqualification due to a grounded knee at Pancrase 295, and following orbital surgery and recovery, he went on to capture the undisputed King of Pancrase belt from Nazareno Malagarie at Pancrase 305 in May 2019. Known to fans simply as “Akira”, he is widely feared as one of the hardest hitting Pancrase Lightweights, and steps away from his 5th ranked spot in the bracket to face Kobayashi. The 33-year-old has faced some of the best from around the world, and will thrive under the pressure of this bout. A change in weight class could be the test he needs right now. The co-main event sees Emiko Raika collide with Takayo Hashi in what promises to be a test of skills and experience, mixed with sheer will-to-win guts and determination. -

Boxing Lessons Download Apple App Boxing Lessons Download Apple App

boxing lessons download apple app Boxing lessons download apple app. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67d94de379b815dc • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Best boxing training apps for Android and iOS. Boxing is one of the most popular sports. If you’ve purchased a punching bag recently or you’re a wannabe boxer, you can learn the sport of boxing from the comfort of your home without spending a dime with the following applications: Best boxing training apps for Android and iOS Kickboxing Fitness Trainer Boxhitt – Boxing / Kickboxing workouts and more Boxtastic: Bag / Shadow Boxing Home HIIT Workouts Boxing Trainer Boxing Round Interval Timer Boxing Training – Offline Videos. Best boxing training apps for Android and iOS. Kickboxing Fitness Trainer. This application teaches kickboxing to its users for free by making them go through various challenges. The challenges are designed for amateur as well as experienced boxers. -

On Modernity, Identity and White-Collar Boxing. Phd

From Rookie to Rocky? On Modernity, Identity and White-Collar Boxing Edward John Wright, BA (Hons), MSc, MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. September, 2017 Abstract This thesis is the first sociological examination of white-collar boxing in the UK; a form of the sport particular to late modernity. Given this, the first research question asked is: what is white-collar boxing in this context? Further research questions pertain to social divisions and identity. White- collar boxing originally takes its name from the high social class of its practitioners in the USA, something which is not found in this study. White- collar boxing in and through this research is identified as a practice with a highly misleading title, given that those involved are not primarily from white-collar backgrounds. Rather than signifying the social class of practitioner, white-collar boxing is understood to pertain to a form of the sport in which complete beginners participate in an eight-week boxing course, in order to compete in a publicly-held, full-contact boxing match in a glamorous location in front of a large crowd. It is, thus, a condensed reproduction of the long-term career of the professional boxer, commodified for consumption by others. These courses are understood by those involved to be free in monetary terms, and undertaken to raise money for charity. As is evidenced in this research, neither is straightforwardly the case, and white-collar boxing can, instead, be understood as a philanthrocapitalist arrangement. The study involves ethnographic observation and interviews at a boxing club in the Midlands, as well as public weigh-ins and fight nights, to explore the complex interrelationships amongst class, gender and ethnicity to reveal the negotiation of identity in late modernity. -

Boxing Edition

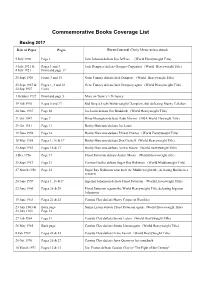

Commemorative Books Coverage List Boxing 2017 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 5 July 1910 Page 3 Jack Johnson defeats Jim Jeffries (World Heavyweight Title) 3 July 1921 & Pages 1 and 3 Jack Dempsey defeats Georges Carpentier (World Heavyweight Title) 4 July 1921 Front and page 17 25 Sept 1926 Front, 3 and 15 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1927 & Pages 1, 3 and 18 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey again (World Heavyweight Title) 24 Sep 1927 Front 1 October 1927 Front and page 5 More on Tunney v Dempsey 19 Feb 1930 Pages 5 and 22 Kid Berg is Light Welterweight Champion after defeating Mushy Callahan 24 June 1937 Page 30 Joe Louis defeats Jim Braddock (World Heavyweight Title) 21 Oct 1947 Page 7 Rinty Monaghan defeats Dado Marino (NBA World Flyweight Title) 29 Oct 1951 Page 11 Rocky Marciano defeats Joe Louis 19 June 1954 Page 14 Rocky Marciano defeats Ezzard Charles (World Heavyweight Title) 18 May 1955 Pages 1, 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Don Cockell (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1955 Pages 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight Title) 3 Dec 1956 Page 17 Floyd Patterson defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight title) 25 Sept 1957 Page 23 Carmen Basilio defeats Sugar Ray Robinson (World Middleweight Title) 27 March 1958 Page 23 Sugar Ray Robinson wins back the Middleweight title, defeating Basilio in a rematch 28 June 1959 Pages 1, 16 &17 Ingemar Johansson defeats Floyd Patterson (World Heavyweight Title) 22 June 1960 Pages 28 & 29 Floyd Patterson -

No Heavyweight Rumor: Ruiz-Arreola, Parker-Chisora Are

No Heavyweight Rumor: Ruiz- Arreola, Parker-Chisora are for real By Norm Frauenheim- The heavyweight division, once revered, has been reduced to a rumor. Only Tyson Fury-Anthony Joshua seems to matter, despite mounting doubts about reported negotiations full of promises and short on specifics. Joshua promoter Eddie Hearn says it will happen this summer. Fury co-promoter Frank Warren says it won’t. That’s where it started months ago. That’s where it still is, although there’s a growing chorus of frustration from Fury and his American promoter Bob Arum, whose skepticism about a $150 million offer from Saudi Arabia was evident in multiple media reports this week. A deal hinges on whether the money is really there. A deal – date and place – has yet to be announced, hence deepening suspicions that the offer is bupkis, just more dust in a Haboob. Meanwhile, Fury has taken to social media and Hearn is his target. Fury, whose trash talk is as deadly as his jab, is ripping Hearn, saying that the UK promoter has cozied up to Canelo Alvarez in the Mexican’s title fight against UK super- middleweight Billy Joe Saunders on May 8 in Arlington, Tex. For the May fight, at least, Hearn is the promoter of record for both. But Fury is questioning his allegiances, which means Hearn is probably as popular as a piñata back home in Britain. Such is that state of the heavyweights, a flagship as rudderless as ever. Yet, chaos at the top hasn’t silenced it. Andy Ruiz Jr. and Chris Arreola, Joe Parker and Derek Chisora will do what Fury and Joshua may — may not — do.