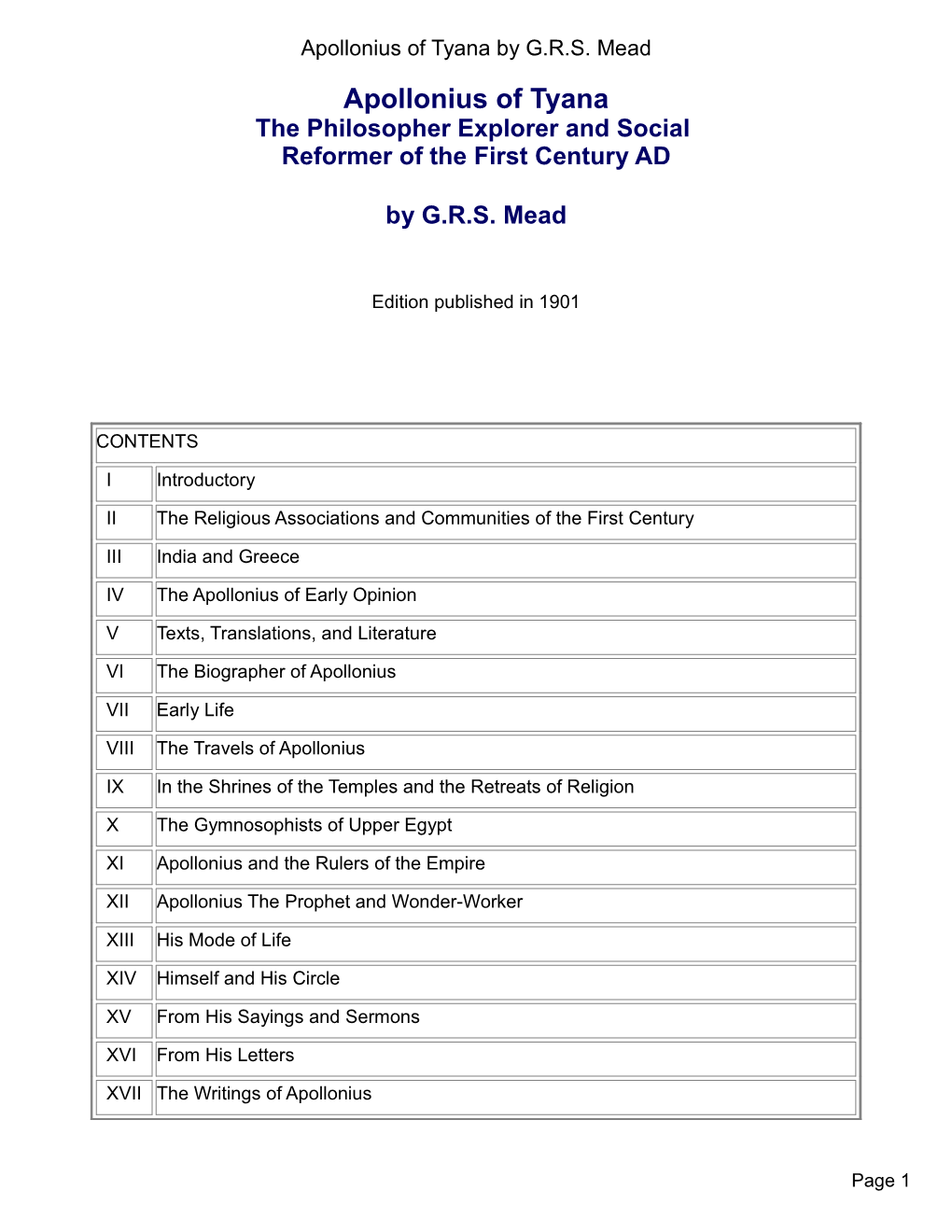

Apollonius of Tyana by GRS Mead

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Death in the Eastern Mediterranean (50–600 A.D.)

Studien und Texte zu Antike und Christentum Studies and Texts in Antiquity and Christianity Herausgeber/Editor: CHRISTOPH MARKSCHIES (Heidelberg) Beirat/Advisory Board HUBERT CANCIK (Tübingen) • GIOVANNI CASADIO (Salerno) SUSANNA ELM (Berkeley) • JOHANNES HAHN (Münster) JÖRG RÜPKE (Erfurt) 12 Antigone Samellas Death in the Eastern Mediterranean (50-600 A.D.) The Christianization of the East: An Interpretation Mohr Siebeck ANTIGONE SAMELLAS, born 1966; 1987 B.A. in Sociology, Connecticut College; 1989 Master of Science in Sociology, London School of Economics; 1993 M.A. in History, Yale University; 1999 Ph.D. in History, Yale University. Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Samellas, Antigone: Death in the Eastern Mediterranean (50-600 A.D.) : the Christianization of the East: an interpretation / Antigone Samellas. - Tübingen : Mohr Siebeck, 2002 (Studies and texts in antiquity and Christianity ; 12) ISBN 3-16-147668-9 © 2002 by J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), P.O.Box 2040, D-72010 Tübingen. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was printed by Guide-Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound by Heinr. Koch in Tübingen. Printed in Germany. ISSN 1436-3003 Preface I am intrigued by subjects that defy the facile scholarly categorizations which assume that the universal and the particular, the objective and the personal, the diachronic and the contingent, belong necessarily to different fields of study. For that reason I chose to examine from a historical perspective phenomena that seem to be most resistant to change: beliefs about the afterlife, attitudes towards death, funerary and commemorative rituals, that is, acts which by definition are characterized by formalism, traditionalism and repetitiveness. -

Julian's Pagan Revival and the Decline of Blood Sacrifice Author(S): Scott Bradbury Source: Phoenix, Vol

Julian's Pagan Revival and the Decline of Blood Sacrifice Author(s): Scott Bradbury Source: Phoenix, Vol. 49, No. 4 (Winter, 1995), pp. 331-356 Published by: Classical Association of Canada Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1088885 . Accessed: 01/11/2013 14:32 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Classical Association of Canada is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Phoenix. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 146.245.216.150 on Fri, 1 Nov 2013 14:32:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions JULIAN'SPAGAN REVIVAL AND THE DECLINE OF BLOOD SACRIFICE SCOTT BRADBURY "This is the chieffruit of piety:to honorthe divinein the traditional ways."7 PorphyryAd Marcellam 18 IT HAS ALWAYS BEEN A PARADOX that in a predominantly pagan empire the EmperorJulian (A.D. 360-363) did not meet with immediatesuccess in his effortsto revivepaganism. Contemporarypagans feltuneasy with Julian'sattempt to make the gods live again in the public consciousness throughthe rebuildingof temples,the revival of pagan priesthoods,the restorationof ancient ceremonies, and most importantly,the revival of blood sacrifices. Historianshave long pointed out that Christianemperors had permittedother elementsof pagan festivalsto continuewhile forbidding blood on the altars, since blood sacrificewas the element of pagan cult most repugnantto Christians.Thus, blood sacrifice,although linked to the fate of pagan cults in general,poses special problemsprecisely because it was regardedas the most loathsomeaspect of cult and aroused the greatest amountof Christianhostility. -

Eunapius' Lives of the Philosophers and Sophists

Histos () liii–lvi REVIEW EUNAPIUS’ LIVES OF THE PHILOSOPHERS AND SOPHISTS Matthias Becker, Eunapios aus Sardes: Biographien über Philosophen und Sophisten. Einleitung, Übersetzung, Kommentar . Roma Aeterna I. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, . Pp. ISBN ----. Hardcover, €.. atthias Becker’s translation of Eunapius of Sardis’ Βίοι φιλοσόφων καὶ σοφιστῶν (hereafter VPS for Vitae philosophorum et sophistarum ) is the first into German, his commentary only the second in any M language on the whole of the work. In both, he has succeeded admirably. I suspect it will be a long time between Becker’s and the next commentary devoted to the VPS , though, as most of us know only too well, curiositas nihil recusat (SHA Aurelian .). As for his translation, I anticipate the story will be different, and that Becker’s version will stimulate the creation of another German translation, free-standing, moderately priced, and, consequently, accessible to a broader readership. Here though, as one would expect from a shortened and revised dissertation (Tübingen, ), Becker’s target is not so much a ‘readership’ as it is a ‘constituency’. This distinction, to the degree it is justified, applies far less to Becker’s translation (pp. –) than to his Commentary (pp. –) and lengthy Introduction (pp. –). The German of his version of the VPS is almost always a clear and accurate rendering of the Greek. But for scholars who will want to see just what it is that Becker has translated, he could have made things easier. As it is, to check the Greek behind his translation requires access to Giuseppe Giangrande’s edition—by far the best of the VPS —, the textual divisions of which Becker follows. -

PAGAN HISTORIOGRAPHY and the DECLINE of the EMPIRE Wolf

CHAPTER SIX PAGAN HISTORIOGRAPHY AND THE DECLINE OF THE EMPIRE Wolf Liebeschuetz Eunapius and his Writings Eunapius1 was about twenty years—one generation—younger than Ammianus Marcellinus. Like Ammianus he was from the Greek- speaking part of the Empire, having been born at Sardis in 347, or more probably in 348,2 to a leading family of the city. But unlike Ammianus he never as far as we know held imperial office either civil or military. So he lacked the connections with court and army which a career in the imperial service might have gained for him. He was a civic notable pure and simple. Judging by what remains of his writings, he was not particularly interested in either administration or warfare, those two staples of classical historiography. He was how- ever highly educated in Greek rhetoric and philosophy and had a strong interest in medicine. His cousin Melite was married to the Neo-Platonist philosopher Chrysanthius, whom Eunapius revered as a teacher, and almost as a father. Chrysanthius was one in the suc- cession of Neo-Platonist philosophers commemorated by Eunapius in his Lives of the Philosophers and Sophists. Eunapius therefore had close personal links with that rather exclusive group of pagan intellectuals.3 Like them, Eunapius devoted his life to the preservation of the Hellenic tradition. In this respect one might compare him with Libanius, about whom we know so much more. It follows that Eunapius’ two works—the History as well as the Lives of the Philosophers and Sophists—were written from a strongly pagan point of view. -

Persecution and Response in Late Paganism The

Persecution and Response in Late Paganism: The Evidence of Damascius Author(s): Polymnia Athanassiadi Source: The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 113 (1993), pp. 1-29 Published by: The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/632395 . Accessed: 01/12/2013 12:02 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Hellenic Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 198.105.44.150 on Sun, 1 Dec 2013 12:02:11 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Journal of Hellenic Studies cxiii (1993) pp 1-29 PERSECUTIONAND RESPONSE IN LATE PAGANISM: THE EVIDENCE OF DAMASCIUS* THE theme of this paper is intolerance: its manifestation in late antiquity towards the pagans of the Eastern Mediterranean,and the immediate reactions and long-term attitudes that it provoked in them. The reasons why, in spite of copious evidence, the persecution of the traditional cults and of their adepts in the Roman empire has never been viewed as such are obvious: on the one hand no pagan church emerged out of the turmoil to canonise its dead and expound a theology of martyrdom, and on the other, whatever their conscious religious beliefs, late antique scholars in their overwhelming majority were formed in societies whose ethical foundations and logic are irreversibly Christian. -

The Cambridge History of Philosophy in Late Antiquity

THE CAMBRIDGE HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY IN LATE ANTIQUITY The Cambridge History of Philosophy in Late Antiquity comprises over forty specially commissioned essays by experts on the philosophy of the period 200–800 ce. Designed as a successor to The Cambridge History of Later Greek and Early Medieval Philosophy (ed. A. H. Armstrong), it takes into account some forty years of schol- arship since the publication of that volume. The contributors examine philosophy as it entered literature, science and religion, and offer new and extensive assess- ments of philosophers who until recently have been mostly ignored. The volume also includes a complete digest of all philosophical works known to have been written during this period. It will be an invaluable resource for all those interested in this rich and still emerging field. lloyd p. gerson is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Toronto. He is the author of numerous books including Ancient Epistemology (Cambridge, 2009), Aristotle and Other Platonists (2005)andKnowing Persons: A Study in Plato (2004), as well as the editor of The Cambridge Companion to Plotinus (1996). The Cambridge History of Philosophy in Late Antiquity Volume I edited by LLOYD P. GERSON cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo, Delhi, Dubai, Tokyo, Mexico City Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 8ru,UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521876421 C Cambridge University Press 2010 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. -

Julian, Paideia and Education

The Culture and Political World of the Fourth Century AD: Julian, paideia and Education Victoria Elizabeth Hughes Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of History, Classics and Archaeology April 2018 Abstract This thesis examines the role of education and paideia in the political and cultural landscape of the mid-fourth century, focusing on the Greek East and the reign of Julian, particularly his educational measures. Julian’s edict and rescript on education are often understood (not least in light of the invectives of Gregory of Nazianzus) as marking an attempt on his part to ban Christians from teaching and, by extension, from engaging in elite public life. They have been used by some scholars as evidence to support the hypothesis that Julian, a committed pagan, implemented an anti-Christian persecution. This thesis reconsiders that hypothesis: it re-evaluates the reign of Julian and his educational measures, and considers the political role of paideia as the culmination and public expression of rhetorical education. Chapter one introduces the topic and provides a brief ‘literature review’ of the key items for a study of Julian and education in the fourth century. Chapter two addresses rhetorical education in the fourth century: it offers a survey of its methods and content, and explores the idea of a ‘typical’ student in contrast with ‘culture heroes’. Chapter three investigates the long-standing Christian debate on the compatibility of a traditional Greek education with Christian belief, and considers the role of Julian in this connection. Chapter four discusses the enhanced status of Latin and of law studies in light of the enlarged imperial administration in the fourth century, and considers the extent to which this development worked to the detriment of rhetorical studies. -

1 UNIT 4 NEOPLATONISM Contents 4. 0. Objectives 4. 1. Introduction 4. 2

UNIT 4 NEOPLATONISM Contents 4. 0. Objectives 4. 1. Introduction 4. 2. The Life and Writings of Plotinus 4. 3. The Philosophy of Plotinus 4. 4. Neoplatonism after Plotinus 4. 5. Let Us Sum Up 4. 6. Key Words 4. 7. Further Readings and References 4. 8. Answers to Check Your Progress 4.0. OBJECTIVES The originality of Plotinus lies basically in the elaboration of a harmonious system out of the main insights that he took from his predecessors. After the death of Plotinus, Neoplatonism continued to flourish in the Syrian School especially, in the School of Athens, in the School at Pergamum and in the Alexandrian school. The influences of Platonism can be seen in the early Christian theologians like St. Augustine. In this unit we shall briefly examine • the life and writings of Plotinus, the founder of Neoplatonism, • the central themes of his philosophical system, • the earlier philosophies from which his system borrows ideas • some philosophical problems of the system and • The post-Plotinian developments of the system in various Schools of the ancient world. 4.1. INTRODUCTION Neoplatonism was the last flowering of the Greek thought in late antiquity. Its birth place was Alexandria, that great city which was founded by Alexander the Great in Egypt and which became a major centre of intellectual activity of the ancient world. Situated at the intersection between the East and the West, Alexandria became the crucible in which the Eastern religious and mystical tendencies freely intermingled with Greek philosophical thought. This cross-cultural fecundation had given birth to Jewish Hellenistic philosophy (founded by Philo) and Neopythagoreanism. -

The Experiences and Education of the Emperor Julian and How It

COMPANION TO THE GODS, FRIEND TO THE EMPIRE: THE EXPERIENCES AND EDUCATION OF THE EMPEROR JULIAN AND HOW IT INFLUE NCED HIS REIGN Marshall Lilly Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2014 APPROVED: Christopher Fuhrmann, Major Professor Laura Stern, Committee Member Robert Citino, Committee Member Richard McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Lilly, Marshall. Companion to the Gods, Friend to the Empire: The Experiences and Education of the Emperor Julian and How It Influenced His Reign 361-363 A.D. Master of Arts (History), August 2014, 108 pp., bibliography, 114 titles. This thesis explores the life and reign of Julian the Apostate the man who ruled over the Roman Empire from A.D. 361-363. The study of Julian the Apostate’s reign has historically been eclipsed due to his clash with Christianity. After the murder of his family in 337 by his Christian cousin Constantius, Julian was sent into exile. These emotional experiences would impact his view of the Christian religion for the remainder of his life. Julian did have conflict with the Christians but his main goal in the end was the revival of ancient paganism and the restoration of the Empire back to her glory. The purpose of this study is to trace the education and experiences that Julian had undergone and the effects they it had on his reign. Julian was able to have both a Christian and pagan education that would have a lifelong influence on his reign. -

Mark Masterson (Victoria University of Wellington)

THE VISIBILITY OF ‘QUEER’ DESIRE IN EUNAPIUS’ LIVES OF THE PHILOSOPHERS Mark Masterson (Victoria University of Wellington) In this talk, I consider the visibility of male homosexual desire that is excessive of age-discrepant and asymmetrical pederasty within a late fourth-century CE Greek text: Eunapius’ Lives of the Philosophers, section 5.2.3-7 (Civiletti/TLG); Wright 459 (pp. 368-370). I call this desire ‘queer’ and I do so because desire between men was not normative in the way pederastic desire was. I engage in the anachronism of saying the word queer to mark this desire as adversarial to normative modes of desire. Its use is an economical signal as to what is afoot and indeed marks an adversarial mode of reading on my part, a reading against some grains then and now. My claim is that desire between adult men is to be found in this text from the late- Platonic milieu. Plausible reception of Eunapius’ work by an educated readership, which was certainly available, argues for this visibility and it is the foundation for my argument. For it is my assertion that the portion of Eunapius’ text I am discussing today is intertextual with Plato’s Phaedrus (255B-E). In his text, Eunapius shows the philosopher Iamblichus (third to the fourth century) calling up two spirits (in the form of handsome boys) from two springs called, respectively, erōs and anterōs. Since this passage is obviously intertextual with the Phaedrus, interpreting it in light of its relation with Plato makes for interesting reading as the circuits of desire uncovered reveal that Iamblichus is both a subject and object of desire. -

History of Philosophy in Late Antiquity

THE CAMBRIDGE HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY IN LATE ANTIQUITY EDITED BY LLOYD GERSON 19 IAMBLICHUS OF CHALCIS AND HIS SCHOOL JOHN DILLON ι LIFE AND WORKS The sources available for our knowledge of Iamblichus' life are highly unsatis factory, consisting as they do primarily of a hagiographical and ill-informed Life by the sophist Eunapius, who was a pupil of Chrysanthius, who was himself a pupil of Iamblichus' pupil Aedesius; nevertheless, enough evidence can be gathered to give a general view of his life-span and activities. The evidence points to a date of birth around 245, in the town of Chalcis-ad- Belum, modern Qinnesrin, in northern Syria. Iamblichus' family were promi nent in the area, and the retention of an old Aramaic name (yamliku-[El]) in the family points to some relationship with the dynasts of Emesa in the previous centuries, one of whose family names this was. This noble ancestry does seem to colour somewhat Iamblichus' attitude to tradition — he likes to appeal on occasion for authority to 'the most ancient of the priests' (e.g., De an. §37), and was plainly a recognized authority on Syrian divinities (cf. Julian, Hymn to King Helios i50cd). As teachers, Eunapius provides (VP 457—8) two names: first, a certain Ana- tolius, described as 'second in command' to the distinguished Platonic philoso pher Porphyry, the pupil of Plotinus, and then Porphyry himself. We are left quite uncertain as to where these contacts took place, but we may presume in Rome, at some time in the 270s or 280s, when Porphyry, on his return from Sicily, had reconstituted Plotinus' school (whatever that involved). -

Astrology in the Early Byzantine Empire and the Anti-Astrology Stance of the Church Fathers

European Journal of Science and Theology, June 2012, Vol.8, No.2, 7-24 _______________________________________________________________________ ASTROLOGY IN THE EARLY BYZANTINE EMPIRE AND THE ANTI-ASTROLOGY STANCE OF THE CHURCH FATHERS Efstratios Theodossiou1, Vassilios Manimanis1 and Milan S. Dimitrijevic2* 1 National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, School of Physics, Department of Astrophysics, Astronomy and Mechanics, Panepistimiopolis, Zografos 15784, Athens, Greece 2 Astronomical Observatory, Volgina 7, 11160 Belgrade, Serbia (Received 7 March 2011) Abstract The peoples of the Roman Empire in the 4th century AD were very superstitious. Sorcery and astrology were widespread in the early Byzantine period. Astrologers, guided by Ptolemy‟s Tetrabiblos, were compiling horoscopes and dream-books, while a common literature were the seismologia, selenodromia and vrontologia, with which people tried to predict the future. It was natural that in this environment many astrologers were famous and they flourished especially in the court of the Emperor Julian (361-363). The Fathers of the Church, however, were clearly against astrology and they were condemning those who wanted to learn about the future events from astrology and other occult practices and pseudo-sciences. Here are presented astrologers Maximus of Ephesus, Paul of Alexandria, Hephaestion of Thebes, Ioannis Laurentius of Lydia and Rhetorius of Byzantium, as well as the Emperor Julian the Apostate, together with the condemnation of astrology by Emperor Honorius and Church Fathers Basil the Great of Cesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, Gregory of Nazianzus, John Chrysostom, the bishop of Jerusalem Cyril I, Epiphanius of Cyprus, Eusebius of Alexandria, Nemesius of Emesa, and Synesius of Cyrene. Keywords: astrology, occult, Byzantine Empire, Tetrabiblos, foretelling, Emperor Julian 1.