Use of Auctions to Assess Consumer Value for Milk from Different Packaging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEW to the MARKET: TWO SPECIALTY BUTTERS Natrel

Press Release For immediate release NEW TO THE MARKET: TWO SPECIALTY BUTTERS Natrel, known for its high-quality dairy products, launches Canada’s first lactose free butter along with an organic butter Montreal, November 8th, 2016 – Natrel, the undisputed dairy market leader across several categories, continues to innovate with the launch of Canada’s first lactose free butter1 in addition to an organic butter. Made of natural ingredients by Agropur, the only dairy cooperative to offer butter made with sea salt, Natrel’s latest products will surely become a butter lover’s dream thanks to their high-quality ingredients. New speciality products An absolute must for anyone who loves authentic taste – nothing beats real butter! That’s exactly why Natrel is launching two new butters, both available in 250 g format, aimed to please lactose-intolerant consumers as well as the ever-growing organic food category. In fact, Canada’s very first lactose free butter was developed to offer a new, appetizing butter option to 7 million lactose intolerant Canadians2. Made with organic cream, Natrel’s new organic butter promises a creamy texture combined with rich taste! Lactose free Butter Organic Butter $4.99 - available in Quebec, Ontario and Atlantic $5.79 – available in Quebec and Ontario provinces Natrel presents the Greatest Dessert Exchange With the holidays fast approaching and just in time with the launch of its two new speciality butters, Natrel kicks off a campaign to spread joy this holiday season! Natrel invites consumers to make their favourite dessert with delicious Natrel products, its two new butters included, offer it to someone close to their heart, and encourage them to continue the dessert chain by doing the same for someone else! It’s a delicious way to celebrate the true values of the holidays. -

4. Key Organic Foods

16 |ORGANIC FOOD PROCESSING IN CANADA Table 4.2. Top Canadian processed organic foods and 4. Key organic foods beverages by number of processors Processed Product Number of In this section, we examine major organic food types Processors in order of sales value. Beverages led organic sales Maple products 227 in 2017 (Table 4.1). Non-alcoholic beverages ranked Non alcoholic beverages 184 first in overall sales, while dairy was the largest selling Baked goods 138 food segment, followed by bakery products and ready Fruits & vegetables 98 meals. Maple products were the number one product Meat products 92 processed by Canadian organic processors (227 Dairy products 71 processors), followed by non-alcoholic beverages Snack foods 70 (184), baked goods (138), fruit and vegetable products Edible oils 55 (98) and meat (88) (Table 4.2). Sauces, dressings & condiments 39 Alcoholic beverages 37 Table 4.1 Top organic packaged foods sold at retail in Breakfast cereals 35 2017, $CAN millions Spreads 28 Processed Product Value Rice & pasta 27 Non alcoholic beverages 779.0 Ready meals 23 Dairy 377.6 Soup 16 Bakery products 237.4 Aquaculture products 8 Alcoholic beverages 230.0 Baby food 6 Ready meals 192.3 Breakfast cereals 132.3 Canadian retail sales values for each of the types Processed fruits/vegetables 86.4 of non-alcoholic beverages are shown in Table 4.3. Snacks 72.6 There were 184 organic non-alcoholic beverage man- Baby food 68.0 ufacturers in 2018, with the majority located in ON. Table 4.4 shows the number of manufacturers for each Meat 64.3 non-alcoholic beverage type. -

List of the Top Dairy Processors in the Dairy 100

DAIRY 100 In Millions Code to Type: C=Cooperative; Pr=Privately-held company; Pu=Publicly-traded company; S=Subsidiary; An asterisk on a sales figure denotes a Dairy Foods estimate. SALES SALES COMPANY LOCATION DAIRY EXECUTIVE TYPE PARENT COMPANY, LOCATION FY END ‘11 ‘10 1. Dean Foods Co. Dallas, TX Gregg Engles, Chairman/CEO Pu 12/31/2011 $12,700 $12,123 Brands: Alpro (Europe), Alta Dena, Arctic Splash, Atlanta Dairies, Barbers, Barbe’s, Berkeley Farms, Broughton, Borden (licensed brand), Brown Cow, Brown’s Dairy, Bud’s Ice Cream, Chug, Country Charm, Country Churn, Country Delite, Country Fresh, Country Love, Creamland, Dairy Fresh, Dean’s, Dipzz, Fieldcrest, Foremost (licensed brand), Friendship, Gandy’s, Garelick Farms, Hershey’s (licensed brand), Horizon Organic, Hygeia, International Delight, Jilbert, Knudsen (licensed brand), LAND O LAKES (licensed brand), Land-O-Sun & design, Lehigh Valley Dairy Farms, Liberty, Louis Trauth Dairy Inc, Maplehurst, Mayfield, McArthur, Meadow Brook, Meadow Gold, Mile High Ice Cream, Model Dairy, Morning Glory, Nature’s Pride, Nurture, Nutty Buddy, Oak Farms, Over the Moon, Pet (licensed brand), Pog (licensed brand), Price’s, Provamel (Europe), Purity, Reiter, Robinson, Saunders, Schenkel’s All*Star, Schepps, Shenandoah’s Pride, Silk, Silk Pure Almond, Silk Pure Coconut, Stok, Stroh’s, Swiss Dairy, Swiss Premium, Trumoo, T.GLee, Tuscan, Turtle Tracks, Verifine, Viva. Products: Milk, cultured dairy, juice/drinks, water, creamers, whipping cream, ice cream mix, ice cream novelties. Plants: Fresh Dairy -

Enhancing the Value of Milk

01 Enhancing the value of milk A vocation for Agropur Each waking day, Agropur cooperative responds to the call of some 4,200 dairy farmers who rely on this organization, which they jointly own, to enhance the fruit of their labour. Over 1.7 billion litres of milk are processed annually in 19 plants, one in the United States and the others in four Canadian provinces. The resulting products grace the tables of thousands of Canadians from coast to coast. But before these products reach their tables, 3,000 employees and many contract agents assigned to milk collection and distribution combine their efforts and expertise to ensure that the final product meets all expectations. OUR PRODUCTS GR EET YOU AT THE CRACK OF DAWN. Tradition and progress co-exist in perfect harmony at Agropur. Their interaction generates amazing results for this Cooperative, which was founded in 1938 and remains rooted in its original values. Its success is, above all, a human story. It is reflected in the quality of services offered and a highly diversified product line, which is in keeping with the latest trends and makes milk, this indispensable resource, ever more enjoyable. Sense of values 02 Nature is our source Closely involved in its members’ activities, Agropur cooperative has made a vocation of enhancing the value of their product, milk. Derived straight from nature, milk comes to the Cooperative full of richness and freshness. Charged with generating a return on this asset, thousands of people invest their genius and talents in this major group project, which is reinvented on a daily basis to respond to needs, expectations and market signals. -

Generations Team Cooperation Variety Satisfaction Innovation Health Legacy Products Evolution Unity Transmission Know-How Employees Foundation Members Values Pure

pride food future authenticity line productivity wisdom challenges consumers knowledge history security friendship guarantee tradition expertisefreshness health needs taste knowledge variety future generations team cooperation variety satisfaction innovation health legacy PRODUCTS evolution unity transmission know-how EMPLOYEES foundation MEMBERS values pure Agropur cooperative 2009 ANNUAL REPORT agropur A look at our roots, our strengths and our future. Every day, the natural goodness of milk improves the lives of consumers by meeting their daily nutritional requirements. An increasing number of people are discovering the Cooperative’s wide range of popular products. To ensure a prosperous future for the Agropur family, the organization relies on its experienced members, passionate employees and incomparable products. These three “families” beat to the rhythm of a single heart, the Cooperative, to the great benefit of everyone involved. The key to its success lies in the strong ties that bind generations of members, the employees and the products that unite them. Today, Agropur has facilities in Canada, the United States and Argentina, and processes over 2.6 billion litres of milk annually. Thanks to the unwavering commitment of its 3,533 members, its 5,225 employees in 27 plants, the Cooperative boasts sales of close to $3.1 billion. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Chairman’s MESSAGE Protect the interests of the Cooperative and its members. At Agropur, a sense of family can be felt throughout the organization. Our members’ know-how is passed down from generation to generation, with several people of the same family working for the Cooperative, and several product families offered to consumers. -

2016 Delegated Authority for the Environmental Services

Document 1 2018 Delegated Authority for the Environmental Services Department under Schedule “I” – Public Works and Environmental Services of Bylaw 2018-397 Section 5 - Discharge Agreements Special Discharge Agreements ($550,565) 1. Algonquin College (Ongoing) 2. Beyond The Pale Brewer (Ongoing) 3. Bicycle Craft Brewery (Ongoing) 4. Broadhead Brewing Company (Ongoing) 5. Big Rig Brewing Company (Ongoing) 6. Canadian Food Inspection Agency- Ottawa Lab Fallowfield (Ongoing) 7. Canadian Linen and Uniform Services Inc. (Ongoing) 8. Cintas (former G&K Services Canada Inc.) (Ongoing) 9. Cleanwear (Independent Linen) (Ongoing) 10. Costco Warehouse #541, Gloucester, Ontario (Ongoing) 11. Costco Warehouse, Kanata, Ontario (Ongoing) 12. Costco Warehouse #540, 1849 Merivale Rd., Ottawa (Ongoing) 13. Costco Warehouse #1263, Barrhaven (New) 14. Deb’s Food Production (Ongoing) 15. Dominion City Brewing Co. (New) 16. DRS Technologies (New) 17. Dustbane Products Ltd. (Ongoing) 18. Dynacare Gamma Laboratory Partnership Revised (Ongoing) 19. Eurofins Environmental Testing Canada Inc. (former Exova) (Ongoing) 20. FarmBoy Central (Ongoing) 21. Flora Hall Brewing (New) 22. Gate Gourmet Canada (Ongoing) 23. Hospital Food Services (Ongoing) 24. Iogen Corporation (Ongoing) 25. Kitchissippi Beer Company (Ongoing) 26. La Cité Collegiale (Ongoing) 27. Lowe-Martin Group Inc. (Ongoing) 28. Lowertown Brewery (New) 29. Mill Street Brew Pub (Ongoing) 30. Municipality of North Grenville, WPCP, Kemptville (Ongoing) 31. NATREL (New: AULT FOODS) (Ongoing) 1 Document 1 32. Nita Beer Company (Ongoing) 33. Novozymes Canada Limited (Ongoing) 34. OC Transpo – 164 Colonnade (Ongoing) 35. OC Transpo – 2550 Queensview (Ongoing) 36. OC Transpo – 1500 St. Laurent (Ongoing) 37. Ottawa Citizen (Oxford Dev Group) (Ongoing) 38. Ottawa Hospital General Campus (Ongoing) 39. -

Layout Concept 2

2006 Annual Report Agropur cooperative Just for you! Agropur For nearly 70 years, Agropur cooperative has worked daily to offer consumers pure, healthy products that can be distinguished by their good taste, authenticity and superior quality. Strengthened by the support of its 3,939 members and 4,000 employees, the Cooperative annually processes nearly 1.9 billion litres of milk in its 20 plants spread throughout Canada and one plant in the United States. With sales of $2.3 billion, Agropur occupies a prime position among the leaders of the Canadian dairy industry. Connected to its milieu, Agropur is constantly in tune with the needs and expectations of its consumers, customers, employees and members, as well as the markets. Agropur. Products just for you. 2 - Agropur cooperative Agropur. Products just for you. Agropur cooperative - 3 Message from the Chairman “Agropur cooperative is an organization in tune with its members.” Since 1938, Agropur has been in tune with its consumers, customers and employees, as well as the market place, and has always strived to respond to the needs and requirements of each. As a cooperative, Agropur is also in tune with its members. In 2002, the latter went through a major reflection process, which paved the way for the adoption, in 2003, of a proposal outlining the organization’s main strategic orientations. Discussions regarding membership subsequently helped bring out members’ reluctance regarding this issue and some requested that reflection on this topic continue over the medium term. Since then, the Canadian and global economic and dairy environments have undergone considerable change. -

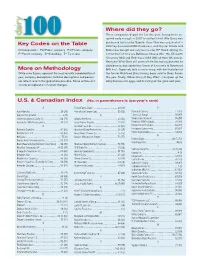

Key Codes on the Table More on Methodology Where Did They

Where did they go? Three companies depart the list this year, having been ac- quired early enough in 2007 to not be listed. Alto Dairy was Key Codes on the Table purchased last year by Saputo, Cass Clay was acquired at in 2007 by Associated Milk Producers, and Crystal Cream and C=Cooperative Pu=Public company Pr=Private company Butter was bought out early last year by HP Hood. Joining the P=Parent company S=Subsidiary T= Tie in rank list for the first time are BelGioso Cheese (No. 75), Ellsworth Creamery (84) and Roth Kase USA (96) all from Wisconsin. Next year Winn-Dixie will come off the list, having divested its dairy processing capabilities (some of it recently to Southeast More on Methodology Milk Inc.). Supervalu tells a similar story, with the final plant of While sales figures represent the most recently completed fiscal the former Richfood Dairy having been sold to Dean Foods year, company descriptions, facilities descriptions and person- this year. Finally, Wilcox Dairy of Roy, Wash., has given up the nel reflect recent changed where possible. Some entries will dairy business for eggs, and its listing will be gone next year. include an explanation of recent changes. U.S. & Canadian Index (No. in parentheses is last year’s rank) A Foster Farms Dairy ....................................... 50 (48) P Agri-Mark Inc. .............................................. 29 (29) Friendly Ice Cream Corp. ...............................55 (56) Parmalat Canada .........................................12 (13) Agropur Cooperative .........................................6 (9) G Perry’s Ice Cream ........................................ 97 (97) Anderson Erickson Dairy Co. ......................... 66 (71) Glanbia Foods Inc. ........................................ 23 (32) Plains Dairy Products ....................................95 (99) Associated Milk Producers Inc. -

CFIA Registered Dairy Establishments

Reg. # Agr. Establishment Name - Nom de l'établissment Also Doing Business Telephone - Téléphone Location Address - Location City - Ville Location Province - Location Postal As (ADBA) - Fait Adresse de lieu de lieu Province de lieu Code Code postal affaires aussi de lieu 37 PARMALAT CANADA INC. (613) 774-2310 490 GORDON STREET WINCHESTER ON K0C 2K0 44 KRAFT HEINZ CANADA ULC (613) 537-8001 70 DICKINSON DR. INGLESIDE ON K0C 1MO 62 GRIFFITH FOODS LIMITED (416) 288-5655 757 PHARMACY AVE. TORONTO ON M1L 3J8 76 BRIGHT CHEESE & BUTTER MANUFACTURING COMPANY LIMITED 519-454-4810 816503 County Rd. #22 BRIGHT ON N0J 1B0 86 GAY LEA FOODS CO-OPERATIVE LIMITED (519) 392-6864 21 CLINTON STREET TEESWATER ON N0G 2S0 92 PARMALAT CANADA INC. (519) 348-8414 100 ST. GEORGE STREET MITCHELL ON N0K 1N0 215 OAK GROVE CHEESE FACTORY LIMITED (519) 662-2539 29 BLEAMS ROAD EAST HAMBURG ON N3A 1G6 277 PARMALAT CANADA INC. 905-641-8151 461 STEWART ROAD NIAGARA ON THE ON L0S-1J0 LAKE 441 GAY LEA FOODS CO-OPERATIVE LIMITED 647-277-4320 100 CLAYSON ROAD TORONTO ON M9M-2G7 511 SAPUTO DAIRY PRODUCTS CANADA G.P. (519) 655-2337 284 HOPE STREET WEST TAVISTOCK ON N0B 2R0 512 THE STIRLING CREAMERY LIMITED 905-283-5220 1 FRONT STREET STIRLING ON K0K-3E0 524 GAY LEA FOODS CO-OPERATIVE LIMITED (519) 822-5530 21 SPEEDVALE AVENUE GUELPH ON N1H 1J5 WEST 541 THE ALLISTON CREAMERY & DAIRY LIMITED (705) 435-6751 26 DOMINION STREET ALLISTON ON L9R 1L5 578 PINE RIVER CHEESE AND BUTTER COOPERATIVE (519) 395-2638 LOT 36, CON. -

Ontario Agropur Cooperative Operating As Natrel Inc

CONTENT COPY OF ORIGINAL Ministry Ministère AMENDED CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL of the de AIR Environment l’Environnement NUMBER 6513-6BSKNX Ontario Agropur Cooperative operating as Natrel Inc. 1001 Dairy Drive Orleans, Ontario K4A 3N3 Site Location: 1001 Dairy Drive Ottawa City, Ontario You have applied in accordance with Section 9 of the Environmental Protection Act for approval of: - two (2) natural gas fired steam boilers having an aggregate thermal input of 11,183,592 kilojoules per hour, exhausting into the atmosphere through two separate stacks, having an exit diameter of 0.35 and 0.40 metre, respectively, each extending 4 metres above the roof and 10.6 metres above grade; - one (1) natural gas fired unit heater, having a maximum thermal input of 261,654 kilojoules per hour, exhausting into the atmosphere through an exhaust having an exit diameter of 0.10 metre, extending 1.21 metres above the roof and 7.21 metres above grade; - three (3) natural gas fired heating, ventilation and air conditioning units for comfort heating purposes, having an aggregate thermal input of 3,667,374 kilojoules per hour, serving the milk pasteurization plant; - ten (10) natural gas fired unit heaters having an aggregate thermal input of 2,637,500 kilojoules per hour, exhausting the products of combustion through ten separate vent stacks each having an exit diameter of 0.1 metre, each extending 1.0 metre above the roof and 7.6 metres above grade; and - one (1) laboratory fume hood exhaust system in the quality control laboratory, having a volumetric flowrate of 0.4 normal cubic metre per second, exhausting through a stack having an exit diameter of 0.2 metre, extending 0.8 metre above the roof and 7.2 metres above grade; all in accordance with the Application for Approval (Air) dated January 7, 2005 and signed by John Baarda, Maintenance Manager of Natrel Inc., and all supporting information associated with the application including additional information provided by Hudon Desbiens St-Germain Environnement inc., dated August 2005, and signed by Jean-Francois Raoult, B.Eng. -

Public Works and Environmental Services of By-Law 2016-369

Document 1 2017 Delegated Authority for the Environmental Services Department under Schedule “I” – Public Works and Environmental Services of By-law 2016-369 Section 5 Discharge Agreements Special Discharge Agreements ($729,144.93) 1. Algonquin College – (Ongoing) 2. Beyond The Pale Brewer - (Ongoing) 3. Bicycle Craft Brewery - (Ongoing) 4. Broadhead Brewing Company – (Ongoing) 5. Big Rig Brewing Company – (Ongoing) 6. Canadian Food Inspection Agency- Ottawa Lab Fallowfield - (Ongoing) 7. Cintas (former G&K Services Canada Inc.) - (New) 8. Cleanwear (Independent Linen) - (Ongoing) 9. Costco Warehouse #541, Gloucester, Ontario - (Ongoing) 10. Costco Warehouse, Kanata, Ontario - (Ongoing) 11. Costco Warehouse #540, 1849 Merivale Rd., Ottawa - (Ongoing) 12. Deb’s Food Production – (Ongoing) 13. DRS Technologies (New) 14. Dustbane Products Ltd. - (Ongoing) 15. Dynacare - Gamma Laboratory Partnership Revised - (Ongoing) 16. Eurofins Environmental Testing Canada Inc. (former Exova) - (New) 17. Exova Canada – (Ongoing) 18. FarmBoy – (New) 19. Gate Gourmet Canada - (Ongoing) 20. G &K Services Canada Inc. – (Ongoing) 21. Hospital Food Services - (Ongoing) 22. Iogen Corporation - (Ongoing) 23. Kitchissippi Beer Company - (Ongoing) 24. La Cité Collegiale – (Ongoing) 25. Lowe-Martin Group Inc. - (Ongoing) 26. Mill Street Brew Pub – (Ongoing) 27. Municipality of North Grenville, WPCP, Kemptville – (Ongoing) 28. NATREL (New: AULT FOODS) - (Ongoing) 29. Nita Beer Company - (Ongoing) 30. Novozymes Canada Limited – (Ongoing) 31. Ottawa Citizen (Oxford Dev Group) – (Ongoing) 32. Ottawa Hospital General Campus – (Ongoing) 33. Professional Mobile Wash – (Ongoing) 2 34. PWGSC Parliamentary Precinct Branch – (Ongoing) 35. Royal Canadian Mint – (New) 36. Saputu Foods Ltd. - (Ongoing) 37. St. Joseph Print Group Inc. - (Ongoing) 38. Surgenor Truck Centre - (Ongoing) 39. Tooth and Nail Brewing Company - (Ongoing) 40. -

DECISÃO DA COMISSÃO De 25 De Março De 1997 Que Estabelece As Listas Provisórias De Estabelecimentos De Países Terceiros

1997D0252 — PT — 09.03.2001 — 009.001 — 1 Este documento constitui um instrumento de documentação e não vincula as instituições " B DECISÃO DA COMISSÃO de 25 de Março de 1997 que estabelece as listas provisórias de estabelecimentos de países terceiros a partir dos quais os Estados-membros autorizam a importação de leite e de produtos à base de leite destinados ao consumo humano (Texto relevante para efeitos do EEE) (97/252/CE) (JO L 101 de 18.4.1997, p. 46) Alterada por: Jornal Oficial n.o página data "M1 Decisão 97/480/CE da Comissão de 1 de Julho de 1997 L 207 1 1.8.1997 "M2 Decisão 97/598/CE da comissão de 25 de Julho de 1997 L 240 8 2.9.1997 "M3 Decisão 97/617/CE da Comissão de 29 de Julho de 1997 L 250 15 13.9.1997 "M4 Decisão 97/666/CE da Comissão de 17 de Setembro de 1997 L 283 1 15.10.1997 "M5 Decisão 98/71/CE da Comissão de 7 de Janeiro de 1998 L 11 39 17.1.1998 "M6 Decisão 98/87/CE da Comissão de 15 de Janeiro de 1998 L 17 28 22.1.1998 "M7 Decisão 98/88/CE da Comissão de 15 de Janeiro de 1998 L 17 31 22.1.1998 "M8 Decisão 98/89/CE da Comissão de 16 de Janeiro de 1998 L 17 33 22.1.1998 "M9 Decisão 98/394/CE da Comissão de 29 de Maio de 1998 L 176 28 20.6.1998 "M10 Decisão 1999/52/CE da Comissão de 8 de Janeiro de 1999 L 17 51 22.1.1999 "M11 Decisão 2001/177/CE da Comissão de 15 de Fevereiro de 2001 L 68 1 9.3.2001 1997D0252 — PT — 09.03.2001 — 009.001 — 2 !B DECISÃO DA COMISSÃO de 25 de Março de 1997 que estabelece as listas provisórias de estabelecimentos de países terceiros a partir dos quais os Estados-membros autorizam a