Development of a Pro-Poor Tourism Industry in Mwanza, Tanzania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

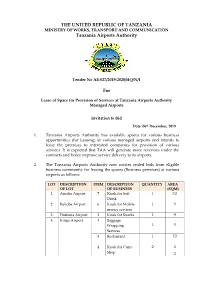

THE UNITED REPUBLIC of TANZANIA Tanzania Airports Authority

THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA MINISTRY OF WORKS, TRANSPORT AND COMMUNICATION Tanzania Airports Authority Tender No AE-027/2019-2020/HQ/N/1 For Lease of Space for Provision of Services at Tanzania Airports Authority Managed Airports Invitation to Bid Date: 06th December, 2019 1. Tanzania Airports Authority has available spaces for various business opportunities (for Leasing) at various managed airports and intends to lease the premises to interested companies for provision of various services. It is expected that TAA will generate more revenues under the contracts and hence improve service delivery to its airports. 2. The Tanzania Airports Authority now invites sealed bids from eligible business community for leasing the spaces (Business premises) at various airports as follows: LOT DESCRIPTION ITEM DESCRIPTION QUANTITY AREA OF LOT OF BUSINESS (SQM) 1. Arusha Airport 7 Kiosk for Soft 1 33 Drink 2. Bukoba Airport 6 Kiosk for Mobile 1 4 money services 3. Dodoma Airport 3 Kiosk for Snacks 1 4 4. Iringa Airport 1 Baggage Wrapping 1 4 Services 3 Restaurant 1 72 4 Kiosk for Curio 2 3 Shop 3 LOT DESCRIPTION ITEM DESCRIPTION QUANTITY AREA OF LOT OF BUSINESS (SQM) 5 Kiosk for Retail 1 3.5 shop 5. Kigoma Airport 1 Baggage Wrapping 1 4 Services 2 Restaurant 1 19.49 3 Kiosk for Retail 2 19.21 shop 4 Kiosk for Snacks 1 9 5 Kiosk for Curio 1 6.8 Shop 6. Kilwa Masoko 1 Restaurant 1 40 Airport 2 Kiosk for soft 1 9 drinks 7. Lake Manyara 2 Kiosk for Curio 10 84.179 Airport Shop 3 Kiosk for Soft 1 9 Drink 4 Kiosk for Ice 1 9 Cream and Beverage Outlet 5 Car Wash 1 49 6 Kiosk for Mobile 1 2 money services 8. -

Geography Teacher’S Guide Senior One

PROTOTYPE GEOGRAPHY TEACHER’S GUIDE SENIOR ONE LOWER SECONDARY CURRICULUM PROTOTYPE PROTOTYPE GEOGRAPHY TEACHER’S GUIDE SENIOR ONE LOWER SECONDARY CURRICULUM SENIOR ONE Published 2020 This material has been developed as a prototype for implementation of the revised Lower Secondary Curriculum and as a support for other textbook development interests. This document is restricted from being reproduced for any commercial gains. National Curriculum Development Centre P.O. Box 7002, Kampala- Uganda www.ncdc.co.ug TECHNOLOGY AND DESIGN PROTOTYPE Contents Preface ....................................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................... v Chapter One: Introduction to Geography ....................................................................................... 1 Chapter Two: Showing the Local Area on a Map .............................................................................. 9 Chapter Three: Maps and Their Use .............................................................................................. 15 Chapter Four: Ways of Studying Geography .................................................................................. 36 Chapter Five: The Earth and its Movements .................................................................................. 51 Chapter Six: Weather and Climate............................................................................................... -

Small-Scale Solar Power Systems for Rural Tanzania: Market Analysis and Opportunities

SMALL-SCALE SOLAR POWER SYSTEMS FOR RURAL TANZANIA: MARKET ANALYSIS AND OPPORTUNITIES The Ohio State University GAP 2017 ENERGY BACKGROUND 3 PROJECT BACKGROUND 4 OVERVIEW OF SOLAR MARKET SEGMENTATION IN TANZANIA 5 EASE OF ADOPTION 9 OVERALL ANALYSIS 9 DEVERGY ANALYSIS 9 CAPITAL REQUIREMENTS 10 PROJECT RISK 10 SCALABILITY OF POWER CONSUMPTION 10 EASE OF ADOPTION 11 THE FAILURE OF MINI-GRIDS TO PROVIDE ELECTRICITY IN TANZANIA 12 THE BATTLE BETWEEN SUPPLY AND DEMAND 12 COMPLICATED PRICING STRUCTURES 12 DYNAMICS OF VILLAGE POLITICS 13 THREAT OF TANESCO 14 THE UKARA ISLAND PROJECT 15 OVERALL ANALYSIS 15 RECOMMENDATIONS 16 DO NOTHING, OR MORE CORRECTLY NEARLY NOTHING 16 CREATE AN ELECTRIC UTILITY 18 APPENDIX 21 1 SOLAR SEGMENTS 21 2 MARKET SEGMENTATION 21 3 PRESENT INSTALLED USER BASE 21 4 KEY FUNDS RAISED BY PAY-AS-YOU-GO COMPANIES 22 5 MEETING NOTES 23 ZOLA SOLAR IN ARUSHA 23 ZOLA – CORPORATE OFFICE 25 POWER PROVIDERS 27 MOBISOL 30 2 Energy Background Tanzania has a significant energy problem. At 15.5%, the country has one of the lowest access percentages in the world, a minor increase from 5.3% in 19901. While 68% of the country’s population resides in rural areas, it is estimated that only 2% of those citizens have access to energy of any form.2 Biomass fuel sources, such as firewood and charcoal, are the dominant energy sources, with kerosene and diesel shortly behind. The national grid, maintained by the parastatal Tanzania Electric Supply Company (TANESCO) under the direction of the Ministry of Energy and Minerals, provides electricity to 10% of the Tanzanian population through the form of petroleum, hydropower, and coal. -

The Somali Maritime Space

LEA D A U THORS: C urtis Bell Ben L a wellin CONTRIB UTI NG AU THORS: A l e x andr a A mling J a y Benso n S asha Ego r o v a Joh n Filitz Maisie P igeon P aige Roberts OEF Research, Oceans Beyond Piracy, and Secure Fisheries are programs of One Earth Future http://dx.doi.org/10.18289/OEF.2017.015 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS With thanks to John R. Hoopes IV for data analysis and plotting, and to many others who offered valuable feedback on the content, including John Steed, Victor Odundo Owuor, Gregory Clough, Jérôme Michelet, Alasdair Walton, and many others who wish to remain unnamed. Graphic design and layout is by Andrea Kuenker and Timothy Schommer of One Earth Future. © 2017 One Earth Future Stable Seas: Somali Waters | i TABLE OF CONTENTS STABLE SEAS: SOMALI WATERS .......................................................................................................1 THE SOMALI MARITIME SPACE ........................................................................................................2 COASTAL GOVERNANCE.....................................................................................................................5 SOMALI EFFORTS TO PROVIDE MARITIME GOVERNANCE ..............................................8 INTERNATIONAL EFFORTS TO PROVIDE MARITIME GOVERNANCE ..........................11 MARITIME PIRACY AND TERRORISM ...........................................................................................13 ILLEGAL, UNREPORTED, AND UNREGULATED FISHING ....................................................17 ARMS TRAFFICKING -

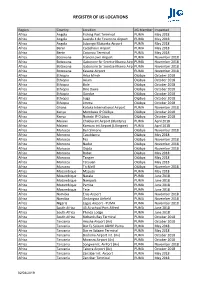

Register of IJS Locations V1.Xlsx

REGISTER OF IJS LOCATIONS Region Country Location JIG Member Inspected Africa Angola Fishing Port Terminal PUMA May 2018 Africa Angola Luanda 4 de Fevereiro Airport PUMA May 2018 Africa Angola Lubango Mukanka Airport PUMA May 2018 Africa Benin Cadjehoun Airport PUMA May 2018 Africa Benin Cotonou Terminal PUMA May 2018 Africa Botswana Francistown Airport PUMA November 2018 Africa Botswana Gaborone Sir Seretse Khama AirpoPUMA November 2018 Africa Botswana Gaborone Sir Seretse Khama AirpoPUMA November 2018 Africa Botswana Kasane Airport PUMA November 2018 Africa Ethiopia Arba Minch OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Axum OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Bole OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Dire Dawa OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Gondar OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Jijiga OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Jimma OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ghana Kotoka International Airport PUMA November 2018 Africa Kenya Mombasa IP OiLibya OiLibya October 2018 Africa Kenya Nairobi IP OiLibya OiLibya October 2018 Africa Malawi Chileka Int Airport (Blantyre) PUMA April 2018 Africa Malawi Kamuzu int.Airport (Lilongwe) PUMA April 2018 Africa Morocco Ben Slimane OiLibya November 2018 Africa Morocco Casablanca OiLibya May 2018 Africa Morocco Fez OiLibya November 2018 Africa Morocco Nador OiLibya November 2018 Africa Morocco Oujda OiLibya November 2018 Africa Morocco Rabat OiLibya May 2018 Africa Morocco Tangier OiLibya May 2018 Africa Morocco Tetouan OiLibya May 2018 Africa Morocco Tit Melil OiLibya November 2018 Africa Mozambique Maputo -

FOUNDATION PROGRAMME OFP 012 Geography

THE OPEN UNIVERSITY OF TANZANIA Institute of Continuing Education FOUNDATION PROGRAMME OFP 012 Geography Published by: The Open University of Tanzania Kawawa Road, P. O. Box 23409, Dar es Salaam. TANZANIA www.out.ac.tz First Edition: 2013 Second Edition: 2017 Copyright © 2013 All Rights Reserved ISBN 978 9987 00 252 8 2 Contents GENERAL INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 6 PART 1 EARTH’S STRUCTURE AND MATERIALS OF EARTH Lecture 1: The Meaning and Branches of Geography ................................................................... 8 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 8 1.2 Geography: An Overview .......................................................................................... 8 Lecture 2: Structure of Earth ....................................................................................................... 12 2.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 12 2.2 The Structure of Earth .............................................................................................. 13 Lecture 3: Origin of Earth ............................................................................................................ 16 3.1 Continental Drifting Theory ..................................................................................... 16 3.2 The Plate Tectonic Theory ...................................................................................... -

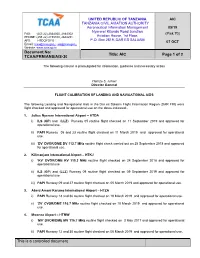

Flight Calibration of Landing and Navigation Aids

UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA AIC TANZANIA CIVIL AVIATION AUTHORITY Aeronautical Information Management 05/19 Nyerere/ Kitunda Road Junction FAX: (255 22) 2844300, 2844302 (Pink 70) Aviation House, 1st Floor, PHONE: (255 22) 2198100, 2844291. P.O. Box 2819, DAR ES SALAAM AFS: HTDQYOYO 07 OCT Email: [email protected], [email protected] Website: www.tcaa.go.tz Document No: Title: AIC Page 1 of 2 TCAA/FRM/ANS/AIS-30 The following circular is promulgated for information, guidance and necessary action Hamza S. Johari Director General FLIGHT CALIBRATION OF LANDING AND NAVIGATIONAL AIDS The following Landing and Navigational Aids in the Dar es Salaam Flight Information Region (DAR FIR) were flight checked and approved for operational use on the dates indicated:- 1. Julius Nyerere International Airport – HTDA i) ILS (GP) and (LLZ) Runway 05 routine flight checked on 11 September 2019 and approved for operational use. ii) PAPI Runway 05 and 23 routine flight checked on 11 March 2019 and approved for operational use. iii) ‘DV’ DVOR/DME DV 112.7 MHz routine flight check carried out on 25 September 2018 and approved for operational use. 2. Kilimanjaro International Airport – HTKJ i) ‘KV’ DVOR/DME KV 115.3 MHz routine flight checked on 24 September 2018 and approved for operational use. ii) ILS (GP) and (LLZ) Runway 09 routine flight checked on 09 September 2019 and approved for operational use. iii) PAPI Runway 09 and 27 routine flight checked on 05 March 2019 and approved for operational use. 3. Abeid Amani Karume International Airport – HTZA i) PAPI Runway 18 and 36 routine flight checked on 10 March 2019 and approved for operational use. -

The Cross and the Crescent in East Africa

The Cross and the Crescent in East Africa An Examination of the Reasons behind the Change in Christian- Muslim Relations in Tanzania 1984-1994 Tomas Sundnes Drønen TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ...................................................................................................................................... 0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION OF THE TOPIC. ............................................................................................................................ 3 PERSONAL INTEREST ........................................................................................................................................... 4 OBJECT AND SCOPE ............................................................................................................................................. 5 APPROACH AND SOURCES ................................................................................................................................... 7 CHAPTER ONE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................... 10 1.1 PRE-COLONIAL TIMES ................................................................................................................................. 10 1.1.1 Early Muslim Settlements .................................................................................................................. -

The Foreign Military Presence in the Horn of Africa Region

SIPRI Background Paper April 2019 THE FOREIGN MILITARY SUMMARY w The Horn of Africa is PRESENCE IN THE HORN OF undergoing far-reaching changes in its external security AFRICA REGION environment. A wide variety of international security actors— from Europe, the United States, neil melvin the Middle East, the Gulf, and Asia—are currently operating I. Introduction in the region. As a result, the Horn of Africa has experienced The Horn of Africa region has experienced a substantial increase in the a proliferation of foreign number and size of foreign military deployments since 2001, especially in the military bases and a build-up of 1 past decade (see annexes 1 and 2 for an overview). A wide range of regional naval forces. The external and international security actors are currently operating in the Horn and the militarization of the Horn poses foreign military installations include land-based facilities (e.g. bases, ports, major questions for the future airstrips, training camps, semi-permanent facilities and logistics hubs) and security and stability of the naval forces on permanent or regular deployment.2 The most visible aspect region. of this presence is the proliferation of military facilities in littoral areas along This SIPRI Background the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa.3 However, there has also been a build-up Paper is the first of three papers of naval forces, notably around the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, at the entrance to devoted to the new external the Red Sea and in the Gulf of Aden. security politics of the Horn of This SIPRI Background Paper maps the foreign military presence in the Africa. -

Environment and Society in Tanzania – Summer 2018 Page 2 Natural Environment

Environment and Society in Tanzania May 14 - 30, 2018 This study abroad program is coordinated by the Northern Illinois University Study Abroad Office (SAO), in cooperation with the NIU Department of Geography at Northern Illinois University, and in collaboration with the University of North Alabama. PROGRAM DATES: The program will officially begin with departure of the group from Chicago O’Hare Airport on May 14, 2018 and will end with the return of the group from Dar es Salam, Tanzania to Chicago on May 30, 2018. PROGRAM DIRECTORS: This program will operate in conjunction with an existing program at the University of North Alabama so there will be one program director from each institution: Courtney Gallaher, from NIU and Francis Koti, from UNA. Dr. Greg Gaston (UNA) will also serve as an instructor for this program. (See Appendix A for more information) Courtney Gallaher is a jointly-appointed Assistant Professor in Geography and Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies at NIU. She has a background in environmental management, natural resource conservation and agriculture and has spent more than fifteen years working in Sub- Saharan Africa. She co-directed a non-profit in Kenya for more than a decade and has traveled and conducted extensive research in East Africa, including Kenya, Tanzania and Malawi. Her research interests focus primarily on sustainable agriculture and food security. As a student she studied abroad in France, Senegal, Kenya and Tanzania so she has a deep appreciation for the benefits of studying abroad. Francis Koti serves as department chair for the Department of Geography at the University of North Alabama. -

This Is a Controlled Document

UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA AIRAC TANZANIA CIVIL AVIATION AUTHORITY AIP Aeronautical Information Services Supplement FAX: (255 22) 2844300, 2844302 Nyerere /Kitunda Road Junction 21/19 PHONE: (255 22) 2198100 AFS: HTDQYOYO Aviation House, 1st Floor, Email: [email protected], [email protected] Website: www.tcaa.go.tz P.O. Box 2819, DAR ES SALAAM 01 August 2019 Document No: Title: AIP Supplement Page 1 of 3 TCAA/FRM/ANS/AIS - 56 Effective Date: 12 September 2019 EN-ROUTE (ENR) S21 MWANZA TERMINAL CONTROL AREA (TMA) 1. OBJECTIVES 1.1. Mwanza Terminal Control Area (TMA) has being established to encompass traffic operating in the area in order to improve safety as well as to reduce workload to DAR ACC. 2. AIRSPACE DIMENSIONS 2.1. Lateral limits 2.1.1. Area bounded by a straight line starting from the Tanzania and Kenya International boundary at a point 01 06 36.59S 034 14 13.00E to; 02 34 58.00S 034 15 35.00E clockwise along an arc of 80NM radius centred at Mwanza Aerodrome Reference Point (ARP) 02 26 38.86S 032 55 54.96E to, 03 46 16.00S 032 37 53.00E along a straight line joining International boundary between Tanzania and Burundi at a point 03 15 21.00S 030 50 22.00E then along the International boundaries of Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda and Kenya to point 01 06 36.59S 034 14 13.00E 2.2. Vertical limits 2.2.1. From 1500 FT AGL to FL245. Note: Mwanza CTR extends from the surface to 10500FT AGL, with 30NM radius centered on the Aerodrome Reference Point (ARP) 02 26 38.86S 032 55 54.96E. -

Liquid Biofuels for Transportation in Tanzania

Liquid Biofuels for Transportation in Tanzania Potential and Implications for Sustainable Agriculture and Energy in the 21st Century Study commissioned by the German Technical Cooperation (GTZ) August 2005 Study funded by BMELV through FNR The views and opinions of the author expressed in this study do not necessarily reflect those of the BMELV Biofuels for Transportation in Tanzania Preface The work was commissioned by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) in Eschborn and makes a contribution to a more comprehensive project on international level that investigates the possible opportunities of biofuels especially in developing countries. Reviewers: Elke Foerster (GTZ), Dirk Assmann (GTZ), Christine Clashausen (GTZ), Birger Kerckow (FNR), Uwe Fritsche (Oeko-Institut). Partnership WIP – Renewable Energies Dr. Rainer Janssen Sylvensteinstrasse 2, 81369 Munich, Germany email: [email protected] http://wip-munich.de Themba Technology Dr. Jeremy Woods Gareth Brown Linden Square, Coppermill Lock, Harefield, Uxbridge UB9 6TQ, United Kingdom email: [email protected] http://www.thembatech.co.uk Tanzania Traditional Energy Development and Environment Organisation (TaTEDO) Estomih N. Sawe P.O. Box 32794, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania Tel. +255 22 2700 –771 (- 438 Fax) email: [email protected] http://www.tatedo.org Integration Umwelt und Energie GmbH Ralph Pförtner Bahnhofstr. 9, 91322 Gräfenberg, Germany Tel. +49 9192 9959 -0 (-10 Fax) email: [email protected] http://www.integration.org 2 Biofuels for Transportation in Tanzania Executive Summary The successful growth of African economies hinges on their modern energy, of which liquid fuel plays an important role. Sharp fluctuations in oil prices have thwarted development plans in Africa and forced many countries to review their development and services project, their overall expenditure and their external trade relations.