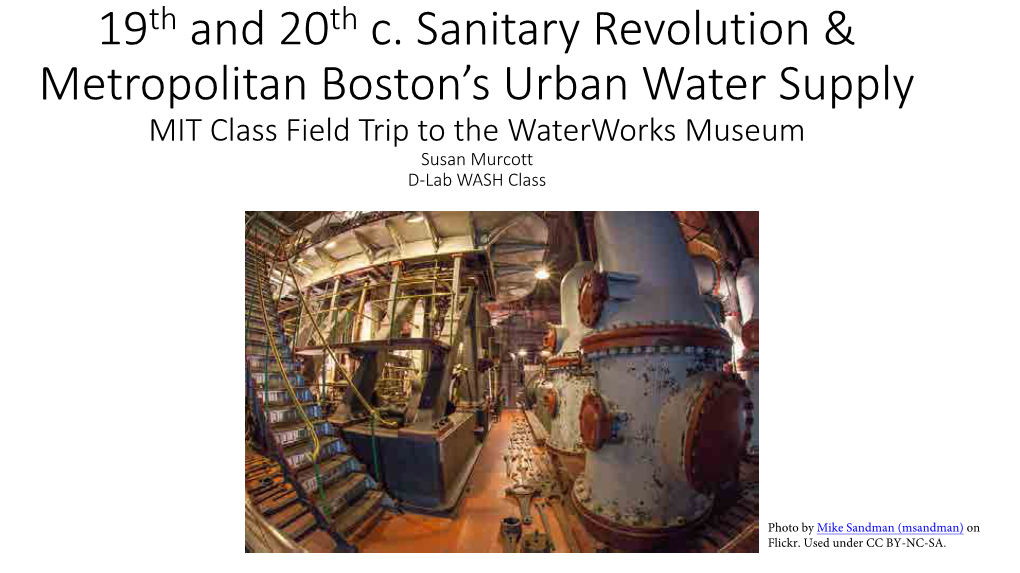

EC.715 D-Lab: Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene, Lecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drinking Water Treatment Systems

Drinking Water Facts….. Drinking Water Treatment Systems By: Barbara Daniels and Nancy Mesner Revised December 2010 If your home water comes from a public water supply, it has been tested and meets EPA standards for drinking water. If you use a private well, however, you are responsible for assuring that the water is safe to drink. This means that you should periodically have your water tested, make sure your well is in proper condition without faulty well caps or seals, and identify and remove potential sources of con- tamination to your well such as leaking septic systems or surface contamination. With a private well, you are also responsible for any treatment your water may need if it contains harm- ful pollutants or contaminants that affect the taste, odor, corrosiveness or hardness of the water. This fact sheet discusses different types of water treatment systems available to homeowners. Addressing the source of the problem is often less costly in the long run than installing and maintaining a water system. For more information on identifying pollutant sources, problems with your well, or help in testing your well water, see the references at the end of this fact sheet. There are many types of water treatment systems available. No one type of treatment can address every water quality problem, so make sure you purchase the type of equipment that can effectively treat your particular water quality issue. The table below can help direct you to the right solution for your prob- lem. Drinking Water Facts….. What type of water treatment is needed? The table below lists common water contamination problems. -

Waterworks System Improvements

Waterworks System Improvements Wachusett Reservoir Integrated Water Supply Improvement Program MWRA’s Integrated Water Supply Improvement Program is an initiative consisting of a series of projects to protect reservoir watersheds, build new water treatment and transmission facilities, upgrade distribution storage and MWRA and community pipelines and interim improvements to the Metropolitan Tunnel system redundancy. The program improves each aspect of the water system from the watersheds to the consumer to ensure that high quality water reliably reaches MWRA customers’ taps. The program began in 1995 with the initial components which were completed by 2005 and the program remains active as the scope was expanded to continue to improve the water system. The main program components are as follows: Watershed Protection The watershed areas around Quabbin and Wachusett Reservoirs are pristine areas with 85% of the land covered in forest or wetlands and about 75% protected from development by direct ownership or development restrictions. MWRA works in partnership with the Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) to manage and protect the watersheds. MWRA also finances all the operating and capital expenses for the watershed activities of DCR and on‐going land acquisition activities. MetroWest Water Supply Tunnel The 17‐mile‐long 14‐foot diameter tunnel connects the new Carroll Water Treatment Plant at Walnut Hill in Marlborough to the greater Boston area. It is now working in parallel with the rehabilitated Hultman Aqueduct to move water into the metropolitan Boston area. Construction began on the tunnel in 1996 and the completed tunnel was placed in service in October 2003. Carroll Water Treatment Plant The water treatment plant in Marlborough began operating in July 2005 and it has a maximum day capacity of 405 million gallons per day. -

19. Water Treatment Plants. the Introduction (Chapter 1) for These

Chapter 4 – Specifications Designs 19. Water Treatment Plants 19. Water Treatment Plants. The Introduction (Chapter 1) for these design data collection guidelines contains additional information concerning: preparing a design data collection request, design data collection requirements, and coordinating the design data collection and submittal. The following is a list of possible data required for specifications design of water treatment facilities. The size and complexity of the process system and structures should govern the amount and detail of the design data required. A. General Map Showing: (1) A key map locating the general map area within the State. (2) The plant site and other applicable construction areas. (3) Existing towns, highways, roads, railroads, public utilities (electric power, telephone lines, pipelines, etc.), streams, stream-gauging stations, canals, drainage channels. (4) Existing or potential areas or features having a bearing on the design, construction, operation, or management of the project feature such as: recreation areas; fish and wildlife areas; building areas; and areas of archeological, historical, and mining or paleontological interest. The locations of these features should bear the parenthetical reference to the agency most concerned: for example Reclamation. (5) County lines, township lines, range lines, and section lines. (6) Locations of construction access roads, permanent roads, and sites for required construction facilities. (7) Sources of natural construction materials and disposal areas for waste material, including the extent of mitigation required. (a) Location of disposal areas for debris, sediment, sludge, and spent chemicals from cleaning or storage solutions. (8) Water sources to be treated such as surface water or underground water. (9) Location of potential waste areas (i.e., channels). -

Household Water Treatment Filters Product Guide Table of Contents

Household Water Treatment Filters Product Guide Table of contents 1. Introduction ...............................................................1 2. Key parameters ............................................................2 3. Filter categories ............................................................4 4. Validation methods .........................................................22 5. Local procurement .........................................................24 First edition, April 2020 Disclaimer: The use of this product guide is strictly for the internal purposes of the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and in no way warrants, represents or implies that it is a complete and thorough evaluation of any of the products mentioned. This guide does not constitute, and should not be considered as, a certification of any of the products. The models and products included in this guide are for information purposes only, the lists are not exhaustive, and they do not represent a catalogue of preferred products. This guide is not to be used for commercial purposes or in any manner that suggests, or could be perceived as, an endorsement, preference for, or promotion of, the supplier’s products by UNICEF or the United Nations. UNICEF bears no responsibility whatsoever for any claims, damages or consequences arising from, or in connection with, the product guide or use of any of the products by any third party. Cover photo: © UNICEF/UNI127727/Vishwanathan 1 Introduction The provision of safe drinking water for all, in an average family size of five persons per sufficient quantities, is a key priority for UNICEF household. Solar disinfection is discussed in this and other water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) guide, as the other main non-chemical method actors, be it at the onset of an emergency or in of water treatment (along with boiling). -

A Practical Guide to Implementing Integrated Water Resources Management and the Role for Green Infrastructure”, J

A Practical Guide to Implementing Integrated Water Resources Management & the Role of Green Infrastructure Prepared for: Prepared for: Funded by: Prepared by: May 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Environmental Consulting & Technology, Inc. (ECT), wishes to extend our sincere appreciation to the individuals whose work and contributions made this project possible. First of all, thanks are due to the Great Lakes Protection Fund for funding this project. At Great Lakes Commission, thanks are due to John Jackson for project oversight and valuable guidance, and to Victoria Pebbles for administrative guidance. At ECT, thanks are due to Sanjiv Sinha, Ph.D., for numerous suggestions that helped improve this report. Many other experts also contributed their time, efforts, and talent toward the preparation of this report. The project team acknowledges the contributions of each of the following, and thanks them for their efforts: Bill Christiansen, Alliance for Water Efficiency James Etienne, Grand River Conservation Christine Zimmer, Credit Valley Conservation Authority Authority Cassie Corrigan, Credit Valley Conservation Melissa Soline, Great Lakes & St. Lawrence Authority Cities Initiative Wayne Galliher, City of Guelph Clifford Maynes, Green Communities Canada Steve Gombos, Region of Waterloo Connie Sims – Office of Oakland County Water Julia Parzens, Urban Sustainability Directors Resources Commissioner Network Dendra Best, Wastewater Education For purposes of citation of this report, please use the following: “A Practical Guide to Implementing -

2016 Stormwater Management Report

Municipality/Organization: Boston Water and Sewer Commission EPA NPDES Permit Number: MASOI000I Report/Reporting Period: January 1. 2016-December 31, 2016 NPDES Phase I Permit Annual Report General Information Contact Person: Amy M. Schofield Title: Project Manager Telephone #: 617-989-7432 Email: [email protected] Certification: I certify under penalty of law that this document and all attachments were prepared under my direction or supervision in accordance with a system designed to assure that qualified personnel properly gather and evaluate the information submitted. Based on my inquiry of the person or persons who manage the system, or those persons directly responsible for gathering the information, the information submitted is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, true, accur’ and complete. I am aware that there are significant penalties for submitting fals in ormation thctuding the possibility of fine and imprisonment for knowing violai Title: Chief Engineer and Operations Officer Date: / TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Permit History…………………………………………….. ……………. 1-1 1.2 Annual Report Requirements…………………………………………... 1-1 1.3 Commission Jurisdiction and Legal Authority for Drainage System and Stormwater Management……………………… 1-2 1.4 Storm Drains Owned and Stormwater Activities Performed by Others…………………………………………………… 1-3 1.5 Characterization of Separated Sub-Catchment Areas….…………… 1-4 1.6 Mapping of Sub-Catchment Areas and Outfall Locations ………….. 1-4 2.0 FIELD SCREENING, SUB-CATCHMENT AREA INVESTIGATIONS AND ILLICIT DISCHARGE REMEDIATION 2.1 Field Screening…………………………………………………………… 2-1 2.2 Sub-Catchment Area Prioritization…………………………………..… 2-4 2.3 Status of Sub-Catchment Investigations……………………….…. 2-7 2.4 Illicit Discharge Detection and Elimination Plan ……………………… 2-7 2.5 Illicit Discharge Investigation Contracts……………….………………. -

CSR Guidelines for Rural Drinking Water Projects

Guide line For CSR Guideline for Rural Drinking Water Projects “Business has a responsibility to give back to CSR Guidelines community” For Rural Drinking Water Projects Government of India Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation 1 | P a g e Guide line For CSR Guideline for Rural Drinking Water Projects Table of Contents Page S.No Topic Number 1. Background 3 2. Why CSR for Drinking Water 3 3. Snapshot of CSR Guide Line 4 4. Objectives with regard to Water 5 5. Methodology 5 6. Type of Activities 5 7. Identification of Gram Panchayat for implementation of Water 6 projects 8. Role of Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation 6 9. Monitoring mechanism 6 10. Tri-partite agreement (TPA) 7 11. Operation and Maintenance 7 12. Conclusion 7 2 | P a g e Guide line For CSR Guideline for Rural Drinking Water Projects 1. Background Due to Poor quality of water and presence of chemical/ bacteriological contamination, many water borne diseases are spread, which causes untold misery, and in several cases even death, thereby adversely affecting the socio-economic progress of the country . From an estimate by WaterAid, it has come out that these diseases negatively effect health and education in children, and further what is worse, 180 million man days approximately are lost in the working population to India every year. Water-related diseases put an economic burden on both the household and the nation’s economy. At household levels, the economic loss includes cost of medical treatment and wage loss during sickness. Loss of working days affects national productivity. -

Read More in the Xylem 2019 Sustainability Report

Water for a Healthy World 1 | Xylem 2019 Sustainability Report Table of Contents 1. Message from Patrick Decker, President & CEO .... 3 2. Message from Claudia Toussaint, SVP, General Counsel & Chief Sustainability Officer . 6 3. How We Think About Sustainability ............... 9 4. How We Make Progress ........................ 24 5. Serving Our Customers ........................ 33 6. Building a Sustainable Company ................ 47 7. Empowering Communities ..................... 80 8. GRI Content Index ............................. 88 ABOUT THIS REPORT We are pleased to present Xylem’s ninth annual Sustainability Report, which describes our efforts in 2019 to solve global water challenges and support a healthy world. The How We Think About Sustainability section of this report explains the connection between current and emerging issues of water scarcity, water systems resilience to climate change and other water challenges and water affordability, and Xylem’s pivotal role in addressing these issues. We close out our goals set in 2014 and share our initial progress report against our 2025 goals, which we introduced in 2019, including Signature Goals designed to tackle some of the world’s most pressing water issues. We have also produced a set of General Disclosures that contain relevant data and information to meet requirements of the GRI Standards: Core Option. This report is available at https://www.xylem.com/en-us/sustainability/ in a downloadable PDF format. 2 | Xylem 2019 Sustainability Report CHAPTER 1 Message from Patrick Decker, President & CEO Water is key to public health and to sustainability. At Xylem, we define sustainability broadly, as responsible practices that strengthen the environment, global economy and society, creating a safer and more equitable world. -

School Idea in Prisons for Adults Albert C

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 5 | Issue 1 Article 7 1914 School Idea in Prisons for Adults Albert C. Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Albert C. Hill, School Idea in Prisons for Adults, 5 J. Am. Inst. Crim. L. & Criminology 52 (May 1914 to March 1915) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE SCHOOL IDEA IN PRISONS FOR ADULTS. ALBERT C. HILL.' The attitude of the public towards its criminals has never been very kindly, just or intelligent. Hatred, revenge, cruelty, indifference, Pharisaism, exploitation have characterized the conduct of society to- wards those, who, for one reason or another, have been branded as crim- inals. Badness has often been tolerated and even condoned, so long as it did not end in conviction by a court, but the convict and the ex- convict have always suffered from the neglect and inhumanity of man. A change in public sentiment, however, is now in progress. Society -is becoming more and more sensitive to the sad cry of neglected chil- dren and to the despairing appeals of helpless and hopeless adults. The sentiment of human brotherhood is growing stronger and the call for help meets with more ready response than formerly. -

Annual Report of the Metropolitan District Commission

Public Document No. 48 W$t Commontoealtfj of iWa&sacfmsfetta ANNUAL REPORT OF THE Metropolitan District Commission For the Year 1935 Publication or this Document Approved by the Commission on Administration and Finance lm-5-36. No. 7789 CONTENTS PAGE I. Organization and Administration . Commission, Officers and Employees . II. General Financial Statement .... III. Parks Division—Construction Wellington Bridge Nonantum Road Chickatawbut Road Havey Beach and Bathhouse Garage Nahant Beach Playground .... Reconstruction of Parkways and Boulevards Bridge Repairs Ice Breaking in Charles River Lower Basin Traffic Control Signals IV. Maintenance of Parks and Reservations Revere Beach Division .... Middlesex Fells Division Charles River Lower Basin Division . Bunker Hill Monument .... Charles River Upper Division Riverside Recreation Grounds . Blue Hills Division Nantasket Beach Reservation Miscellaneous Bath Houses Band Concerts Civilian Conservation Corps Federal Emergency Relief Activities . Public Works Administration Cooperation with the Municipalities . Snow Removal V. Special Investigations VI. Police Department VII. Metropolitan Water District and Works Construction Northern High Service Pipe Lines . Reinforcement of Low Service Pipe Lines Improvements for Belmont, Watertown and Arlington Maintenance Precipitation and Yield of Watersheds Storage Reservoirs .... Wachusett Reservoir . Sudbury Reservoir Framingham Reservoir, No. 3 Ashland, Hopkinton and Whitehall Reservoirs and South Sud- bury Pipe Lines and Pumping Station Framingham Reservoirs Nos. 1 and 2 and Farm Pond Lake Cochituate . Aqueducts Protection of the Water Supply Clinton Sewage Disposal Works Forestry Hydroelectric Service Wachusett Station . Sudbury Station Distribution Pumping Station Distribution Reservoirs . Distribution Pipe Lines . T) 11 P.D. 48 PAGE Consumption of Water . 30 Water from Metropolitan Water Works Sources used Outside of the Metropolitan Water District VIII. -

Report of the Board of Metropolitan Park Commissioners (1898)

A Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/reportofboardofm00mass_4 PUBLIC DOCUMENT No. 48. REPORT ~ Board of Metropolitan Park Commissioners. J^ANUARY, 1899. BOSTON : W RIGHT & POTTER PRINTING CO., STATE PRINTERS, 18 Post Office Square. 1899. A CONTENTS. PAGE Report of the Commissioners, 5 Report of the Secretary, 18 Report of the Landscape Architects, 47 Report of the Engineer, 64 Financial Statement, . 86 Analysis of Payments, 99 Claims (chapter 366 of the Acts of 1898), 118 KEPOKT. The Metropolitan Park Commission presents herewith its sixth annual report. At the presentation of its last report the Board was preparing to continue the acquirement of the banks of Charles River, and was engaged in the investigation of avail- able shore frontages and of certain proposed boulevards. Towards the close of its last session the Legislature made an appropriation of $1,000,000 as an addition to the Metropolitan Parks Loan, but further takings were de- layed until the uncertainties of war were clearly passed. Acquirements of land and restrictions have been made or provided for however along Charles River as far as Hemlock Gorge, so that the banks for 19 miles, except where occu- pied by great manufacturing concerns, are in the control either of this Board or of some other public or quasi public body. A noble gift of about 700 acres of woods and beau- tiful intervales south of Blue Hills and almost surroundingr Ponkapog Pond has been accepted under the will of the late ' Henry L. Pierce. A field in Cambridge at the rear of « Elm- wood," bought as a memorial to James Russell Lowell, has been transferred to the care of this Board, one-third of the purchase price having been paid by the Commonwealth and the remaining two-thirds by popular subscription, and will be available if desired as part of a parkway from Charles River to Fresh Pond. -

Tracing the Aqueducts Through Newton

Working to preserve open space in Newton for 45 years! tthhee NNeewwttoonn CCoonnsseerrvvaattoorrss NNEEWWSSLLEETTTTEERR Spring Issue www.newtonconservators.org April / May 2006 EXPLORING NEWTON’S HISTORIC AQUEDUCTS They have been with us for well over a century, but the Cochituate and Sudbury Aqueducts remain a PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE curiosity to most of us. Where do they come from and where do they go? What are they used for? Why Preserving Echo Bridge are they important to us now? In this issue, we will try to fill in some of the blanks regarding these As part of our planning for the aqueducts in fascinating structures threading their way through our Newton, we cannot omit Echo Bridge. This distinctive city, sometimes in clear view and then disappearing viaduct carried water for decades across the Charles into hillsides and under homes. River in Newton Upper Falls from the Sudbury River to To answer the first question, we trace the two Boston. It is important to keep this granite and brick aqueducts from their entry across the Charles River structure intact and accessible for the visual beauty it from Wellesley in the west to their terminus in the provides. From a distance, the graceful arches cross the east near the Chestnut Hill Reservoir (see article on river framed by hemlocks and other trees. From the page 3). Along the way these linear strands of open walkway at the top of the bridge, you scan the beauty of space connect a series of parks and playgrounds. Hemlock Gorge from the old mill buildings and falls th The aqueducts were constructed in the 19 upriver to the meandering water and the Route 9 century to carry water from reservoirs in the overpass downstream.