Wüster's View of Terminology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EPONYMS in DERMATOLOGY LITERATURE LINKED to GENITAL SKIN DISORDERS Khalid Al Aboud1, Ahmad Al Aboud2

Historical Article DOI: 10.7241/ourd.20132.60 EPONYMS IN DERMATOLOGY LITERATURE LINKED TO GENITAL SKIN DISORDERS Khalid Al Aboud1, Ahmad Al Aboud2 1Department of Public Health, King Faisal Hospital, Makkah, Saudi Arabia Source of Support: 2Dermatology Department, King Abdullah Medical City, Makkah, Saudi Arabia Nil Competing Interests: None Corresponding author: Dr. Khalid Al Aboud [email protected] Our Dermatol Online. 2013; 4(2): 243-246 Date of submission: 24.09.2012 / acceptance: 04.11.2012 Cite this article: Khalid Al Aboud, Ahmad Al Aboud: Eponyms in dermatology literature linked to genital skin disorders. Our Dermatol Online. 2013; 4(2): 243-246. There are numerous eponymous systemic diseases which of Nazi party membership, forced human experimentation may affect genital skin or sexual organs in both genders. For in the Buchenwald concentration camp, and subsequent example Behçet disease which is characterized by relapsing prosecution in Nuremberg as a war criminal, have come to oral aphthae, genital ulcers and iritis. light. This disease is named after Hulusi Behçet [1] (1889–1948), One more example is syphilis. In 1530, the name „syphilis” (Fig. 1), the Turkish dermatologist and scientist who was first used by the Italian physician and poet Girolamo first recognized the syndrome. This disease also called Fracastoro [4] (1478-1553), as the title of his Latin poem „Adamantiades’ syndrome” or „Adamandiades-Behçet in dactylic hexameter describing the ravages of the disease syndrome”, for the work done by Benediktos Adamantiades. in Italy. In his well-known poem „Syphilidis sive de morbo Benediktos Adamantiades (1875-1962), (Fig. 2) was a Greek gallico libri tres” (Three books on syphilis or the French ophthalmologist [2]. -

English and Translation in the European Union

English and Translation in the European Union This book explores the growing tension between multilingualism and mono- lingualism in the European Union in the wake of Brexit, underpinned by the interplay between the rise of English as a lingua franca and the effacement of translations in EU institutions, bodies and agencies. English and Translation in the European Union draws on an interdisciplinary approach, highlighting insights from applied linguistics and sociolinguistics, translation studies, philosophy of language and political theory, while also look- ing at official documents and online resources, most of which are increasingly produced in English and not translated at all – and the ones which are translated into other languages are not labelled as translations. In analysing this data, Alice Leal explores issues around language hierarchy and the growing difficulty in reconciling the EU’s approach to promoting multilingualism while fostering monolingualism in practice through the diffusion of English as a lingua franca, as well as questions around authenticity in the translation process and the bound- aries between source and target texts. The volume also looks ahead to the impli- cations of Brexit for this tension, while proposing potential ways forward, encapsulated in the language turn, the translation turn and the transcultural turn for the EU. Offering unique insights into contemporary debates in the humanities, this book will be of interest to scholars in translation studies, applied linguistics and sociolinguistics, philosophy and political theory. Alice Leal is Senior Lecturer at the Centre for Translation Studies of the Uni- versity of Vienna, Austria. Routledge Advances in Translation and Interpreting Studies Titles in this series include: 63 English and Translation in the European Union Unity and Multiplicity in the Wake of Brexit Alice Leal 64 The (Un)Translatability of Qur’anic Idiomatic Phrasal Verbs A Contrastive Linguistic Study Ali Yunis Aldahesh 65 The Qur’an, Translation and the Media A Narrative Account Ahmed S. -

Incidence of Reactive Arthritis & Other Musculoskeletal Sequelae of Enteric Bacterial Infection in Oregon: a Population-Base

10/29/2013 Oregon Health & Science University Wins the Knowledge Bowl ACR 2013: Go Portlandumabs!! REACTIVE ARTHRITIS IN 2013: WHAT HAVE WE LEARNT? Atul Deodhar MD Professor of Medicine Division of Arthritis & Rheumatic Diseases Oregon Health & Science University Portland, OR Disclosures Evidence-Based Medicine 1. Townes JM, Deodhar AA, Smith K, et al. Rheumatologic • Honoraria, Advisory Boards: Abbvie, MSD, Novartis, Sequelae of Enteric Bacterial Infection in Minnesota and Pfizer, UCB Oregon: A Population-based Study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1689-96. • Research Grants: Abbvie, Amgen, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB 2. On the difficulties of establishing a consensus on the definition of and diagnostic investigations for reactive arthritis. Results and discussion of a questionnaire prepared for the 4th International Workshop on Reactive Arthritis, Berlin, Germany, July 3-6, 1999.Braun J. et al. J Rheumatol. 2000 Sep;27(9):2185-92. 3. Comparison of sulfasalazine and placebo in the treatment of reactive arthritis (Reiter's syndrome). A Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study. Clegg DO. et al. Arthritis Rheum. 1996 Dec;39(12):2021- 7. What is Reactive Arthritis? Reactive Arthritis • “Arthritis associated with demonstrable infection at a distant site without traditional evidence of sepsis at the affected joint(s)” Andrew Keat, Adv Exp Med Biol 1999;455:201-6 • Classical Pathogens : Chlamydia trachomatis, Yersinia, Salmonella, Shigella & Campylobacter (perhaps Clostridium difficile, Chlamydia pneumoniae & BCG instillation in bladder) • Interval -

Roman Jakobson and the Birth of Linguistic Structuralism

Sign Systems Studies 39(1), 2011 Roman Jakobson and the birth of linguistic structuralism W. Keith Percival Department of Linguistics, The University of Kansas 3815 N. E. 89th Street, Seattle, WA 98115, U.S.A e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The term “structuralism” was introduced into linguistics by Roman Jakobson in the early days of the Linguistic Circle of Prague, founded in 1926. The cluster of ideas defended by Jakobson and his colleagues can be specified but differ considerably from the concept of structuralism as it has come to be understood more recently. That took place because from the 1930s on it became customary to equate structuralism with the ideas of Ferdinand de Saussure, as expounded in his posthumous Cours de linguistique générale (1916). It can be shown, however, that Jakobson’s group rejected Saussure’s theory for ideological reasons. As the term “structuralism” became more widely used it came to be associated with posi- tivist approaches to linguistics rather than with the original phenomenological orientation that had characterized the Linguistic Circle of Prague. The purpose of this paper is to clarify these different approaches and to suggest that because of its extreme porosity the word “structuralism” is an example of a “terminological pandemic”. More research on the varied uses to which the key terms “structure” and “structuralism” were put will undoubtedly further elucidate this important episode in 20th-century intellectual history. 1. Introduction In this article, I shall examine the early history of linguistic structu- ralism and the role played in it by the Russian philologist and linguist Roman Jakobson (1896–1982). -

The Function of Selection in Nazi Policy Towards University Students 1933- 1945

THE FUNCTION OF SELECTION IN NAZI POLICY TOWARDS UNIVERSITY STUDENTS 1933- 1945 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial hlfillment of the requirernents for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History York University North York, Ontario December 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliogaphic Services se~cesbibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada Your tlk Votre refénmce Our fi& Notre refdrence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of ths thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or elecîronic formats. la forme de microfiche/tilm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in ths thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be p~tedor othewise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author' s ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Towards a New Genus of Students: The Function of Selection in Nazi Policy Towards University Students 1933-1945 by Béla Bodo a dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of York University in partial fulfillment of the requirernents for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Permission has been granted to the LIBRARY OF YORK UNlVERSlrY to lend or seIl copies of this dissertation, to the NATIONAL LIBRARY OF CANADA to microfilm this dissertation and to lend or sel1 copies of the film. -

Otto Jespersen and 'The Woman', Then and Now

Otto Jespersen and 'The Woman', then and now Author: Margaret Thomas Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:107506 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Post-print version of an article published in Historiographia Linguistica 40(3): 377-408. doi:10.1075/hl.40.3.03tho. These materials are made available for use in research, teaching and private study, pursuant to U.S. Copyright Law. The user must assume full responsibility for any use of the materials, including but not limited to, infringement of copyright and publication rights of reproduced materials. Any materials used for academic research or otherwise should be fully credited with the source. The publisher or original authors may retain copyright to the materials. HL 40:3 (2013): Article Otto Jespersen and “The Woman”, then and now Margaret Thomas Boston College 1. Introduction The Danish linguist Otto Jespersen (1860–1943) published Language, its Nature, Development and Origin in 1922, more than 90 years ago. Written in English, it was apparently addressed to a readership of students of language (Jespersen 1995 [1938]: 208-210). Jespersen was by then deep into his career as a celebrated scholar of Germanic, historical, and descriptive linguistics. About midway through his book, an 18-page Chapter 13 appears, entitled “The Woman”. This article focuses on “The Woman”, a text that has served since the 1970s as a touchstone for feminist narratives of the history of the discussion of language and gender.1 Modern treatment of Jespersen’s Chapter 13 typically casts Jespersen into the role of mouthpiece for ideas about women and language that contemporary scholars have discredited. -

Reiter's Disease*

Br J Vener Dis: first published as 10.1136/sti.35.2.101 on 1 June 1959. Downloaded from Brit. J. vener. Dis. (1959), 35, 101. REITER'S DISEASE* BY HAMILTON BAILEY AND W. J. BISHOP Reiter's disease is characterized by non-gonococcal purulent urethritis followed in 2 to 14 days by arthritis and conjunctivitis. The arthritis is very painful, and is punctuated by remissions and exacer- bations. The knees, the great toe joints, and the interphalangeal joints are affected most often, but other joints are frequently involved. The con- junctivitis is severe and long-lasting. Complications such as iritis are not uncommon. Intermittent pyrexia, night sweats, and secondary anaemia are the rule. The disease often continues for months or years, and in spite of intensive research, neither the cause nor any effective treatment has yet been found. Hans Reiter was born in 1881 in Leipzig, the son of a manufacturer and owner of a factory. After FIG. 1.-Hans Reiter, b. 1881. Reiter had matriculated from the Thomas Gym- nasium at the age of 20, he commenced his medical Western Front, and in September, while stationed at http://sti.bmj.com/ studies in the University of Leipzig, and continued Chauny, France, he was called upon to care for a them in Breslau and Tubingen. In 1906 he graduated number of soldiers suffering from Weil's disease. It M.D. Leipzig, and then undertook post-graduate was here that he made his first great discovery-he training in bacteriology and hygiene. This prolonged found the causative organism of Weil'st disease, the study was exceptionally thorough and highly cos- Leptospira icterohaemorrhagiae, by inoculating in- mopolitan. -

Reiter's Syndrome

ARCHIWUM HISTORII I FILOZOFII MEDYCYNY 2011, 74, 91-93 GEORGE M. WEISZ “Reiter’s Syndrome” — Ignorance or Plagiarism „Syndrom Reitera” — brak wiedzy czy plagiat School of History (Program in History of Medicine), University of New South Wales, Sydney, and School of Humanities, University of New England, Armidale, NSW, Australia Streszczenie Summary Reaktywne zapalenie stawów to najnowsza nazwa okreś Reactive arthritis is the latest and the final name accorded lająca zapalną, surowiczo-ujemną chorobę stawów, będą to an inflammatory, sero-negative joint disease, a reac cą reakcją na różnego rodzaju choroby żołądkowo-jelito- tion to various gastrointestinal diseases. Introduced by we. Wspomniany syndrom, przedstawiony początkowo Hans Reiter in 1916 and parallel by Fiessinger and Leroy, przez Hansa Reitera w 1916 roku i równocześnie przez the syndrome was adopted in the medical literature as Fiessingera i Leroya, przyjął się w literaturze medycznej “Reiters disease”. Reviewing the past however, it shows jako „choroba Reitera”. W rzeczywistości syndrom zo that the syndrome was in detailed published by B. Brodie stał już szczegółowo opisany przez B. Brodiego sto lat a century before. Reiter s name was compromised by his wcześniej. Sam Reiter skompromitował się, popełniając medical crimes during the Nazi and he was convicted zbrodnie medyczne w okresie nazistowskim, za które in Nuremberg. Was this plagiarism or ignorance? In any został skazany w procesie norymberskim. Czy był to event, Reiter s name ought to be removed both for prob plagiat, czy też brak wiedzy? Tak czy inaczej nazwisko able plagiarism and for medical crimes and credit should Reitera powinno zostać usunięte z nazewnictwa me be accorded to the first describer. -

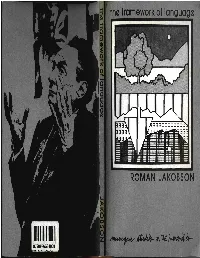

The Framework of Language

© 1980 by Roman Jakobson CONTENTS Michigan Studies in the Humanities VI Horace H. Rackham School ofGraduate Studies Preface Introduction (by Ladislav Matejka) vii Board ofEditors A Glance at the Development of Semiotics Richard Bailey (English), Judith Becker (Music), Arthur Burks (Philosophy), Oscar Blide! (Italian), Vern Carroll (Anthropology), A Few Remarks on Peirce, Herbert Eagle (Film), Emery George (German), Floyd Gray (French), Pathfinder in the Science of Language 31 D. Kirkpatrick (History of Art), Ladislav Matejka (SlaVic), Walter Mignolo (Spanish), Eric Rabkin (American Studies), G. Rosenwald Glosses on the Medieval Insight (psychology), lngo Seidler (German), Gernot Windfuhr (Near into the Science of Language 39 Eastern Studies). The Twentieth Century in European and American Linguistics: Movements and Continuity 61 Irwin R. Titunik,Associate Editor Ladislav Matejka, Managing Editor Metalanguage as a Linguistic Problem 81 On Aphasic Disorders from a Linguistic Angle 93 library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data On the Linguistic Approach to the Problem of Consciousness and the Unconscious 113 Jakobson, Roman, 1896- The framework of language. (Michigan studies in the humanities; no. 1) Includes bibliography. 1. Linguistics-Collected works. I. Title. II. Series. P27J338 410 80-13842 ISBN 0-936534-00-1 PREFACE INTRODUCTION With this volume ,Michigan Studies in the Humanities inaugurates The ever expanding bibliography of Roman Jakobson's contribu a series of books designed to promote cooperation among the various tions to the humanities recently prompted an editor of one of the branches of the humanities by presenting perspectives on traditional numerous Festschrifts in Jakobson's honor to dub him a "polyhistor," 1 problems of interpretation and evaluation. -

Newmeyer for Moeschler Final

AMERICAN LINGUISTS LOOK AT SWISS LINGUISTICS, 1925-1940• Frederick J. Newmeyer ([email protected]) Swiss linguistic research did not have a major impact on American linguistics in the inter-war period. Nevertheless, there was a perhaps surprising awareness of the results of Swiss scholars among American linguists active in that period. This paper documents both recognition given to Swiss scholars by the Linguistic Society of America and the numerous references to the work of the linguists of the Geneva School. 1. INTRODUCTION This paper probes a small, but nonetheless interesting, chapter in the history of linguistics. Ferdinand de Saussure’s Cours de linguistique générale (Saussure 1916) had been published in 1916 and by a decade later was being heralded as a landmark work of linguistic theory, at least in Europe. Saussure’s colleagues and their students had established a major school of linguistics in Geneva and, elsewhere in Switzerland, linguistics was thriving as well. The question is to what extent Swiss linguistic research was of interest to scholars in the United States. In a major historiographical study, Falk (2004) documents the lack of impact that Saussure’s book had among American researchers. While it is not my intention to dispute any of Falk’s findings, one might be tempted, after reading her paper, to draw the conclusion that Swiss linguistics was either unknown or ignored by American practitioners. What follows is a corrective to that possible conclusion. Without wishing to exaggerate American interest, I show below that there was regular notice taken in the period 1925-1940 by American linguists to the work of their Swiss counterparts, as well as recognition of the achievements of the latter by the former. -

Smoking and Death. Public Health Measures Were Taken More Than 40

LETTERS and death indicated strong risks-similar in magnitude to 1 Peto R. Smoking and death: the past 40 years and the next 40. Smoking those found by later studies-whatever control BMJ 1994;309:937-9. (8 October.) 2 Proctor RN. Racial hygiene. Medicne under the Nazis. Cam- Public health measures were taken more group was used (table); these risks were not bridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1988. than 40 years ago explicable in terms of changes in smoking 3 Reiter H. Ansprache bei der Er6ffnung des 1. Wissenschaft- behaviour induced by illness. Schoninger's study lichen Instituts zur Erforschung der Tabakgefahren an EDrroR,-Richard Peto discusses the failure of cost 173.30 of the 100000 Reichsmark given by der Friedrich-Schiller-Universitit Jena am 5 April 1941. public health with regard to smoking over the past Adolf Hitler from his personal funds to the Jena ManchenerMedizinische Wochenschnift 1941;88:697-9. 4 Berlin: stimulants endanger public health. JAMA 1939;12: 40 years,' but his account could have extended Institute. 2339-40. back further. He considers that the Medical 5 Lickint F. Tabak und Organismus. Stuttgart: Hippokrates- Research Council was, in 1957, "the first national Verlag, 1939. institution in the world to accept formally the 6 Davey Smith G, Strobele SA, Egger M. Smoking and health promotion in Nazi Germany. I Epidemiol Community Health evidence that tobacco is a major cause of death." 1994;48:220-3. The formal recognition of this fact, however, was 7 Schairer E, Schoniger E. Lungenkrebs und Tabakverbrauch. explicitly made by many important national insti- ZeitschriftftilrKrebsforschung 1943;54:261-9. -

Medical Ethics in the 70 Years After the Nuremberg Code, 1947 to the Present

wiener klinische wochenschrift The Central European Journal of Medicine 130. Jahrgang 2018, Supplement 3 Wien Klin Wochenschr (2018) 130 :S159–S253 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-018-1343-y Online publiziert: 8 June 2018 © The Author(s) 2018 Medical Ethics in the 70 Years after the Nuremberg Code, 1947 to the Present International Conference at the Medical University of Vienna, 2nd and 3rd March 2017 Editors: Herwig Czech, Christiane Druml, Paul Weindling With contributions from: Markus Müller, Paul Weindling, Herwig Czech, Aleksandra Loewenau, Miriam Offer, Arianne M. Lachapelle-Henry, Priyanka D. Jethwani, Michael Grodin, Volker Roelcke, Rakefet Zalashik, William E. Seidelman, Edith Raim, Gerrit Hohendorf, Christian Bonah, Florian Schmaltz, Kamila Uzarczyk, Etienne Lepicard, Elmar Doppelfeld, Stefano Semplici, Christiane Druml, Claire Whitaker, Michelle Singh, Nuraan Fakier, Michelle Nderu, Michael Makanga, Renzong Qiu, Sabine Hildebrandt, Andrew Weinstein, Rabbi Joseph A. Polak history of medicine Table of contents Editorial: Medical ethics in the 70 years after the Nuremberg Code, 1947 to the present S161 Markus Müller Post-war prosecutions of ‘medical war crimes’ S162 Paul Weindling: From the Nuremberg “Doctors Trial” to the “Nuremberg Code” S165 Herwig Czech: Post-war trials against perpetrators of Nazi medical crimes – the Austrian case S169 Aleksandra Loewenau: The failure of the West German judicial system in serving justice: the case of Dr. Horst Schumann Miriam Offer: Jewish medical ethics during the Holocaust: the unwritten ethical code From prosecutions to medical ethics S172 Arianne M. Lachapelle-Henry, Priyanka D. Jethwani, Michael Grodin: The complicated legacy of the Nuremberg Code in the United States S180 Volker Roelcke: Medical ethics in Post-War Germany: reconsidering some basic assumptions S183 Rakefet Zalashik: The shadow of the Holocaust and the emergence of bioethics in Israel S186 William E.