Mechanistic Mathematical Modeling of Spatiotemporal Microtubule Dynamics and Regulation in Vivo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tsvi Tlusty – C.V

TSVI TLUSTY – C.V. 06/2021 Center for Soft and Living Matter, Institute for Basic Science, Bldg. (#103), Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology, 50 UNIST-gil, Ulju-gun, Ulsan 44919, Korea email: [email protected] homepage: life.ibs.re.kr EDUCATION AND EMPLOYMENT 2015– Distinguished Professor, Department of Physics, UNIST, Ulsan 2015– Group Leader, Center for Soft and Living Matter, Institute for Basic Science 2011–2015 Long-term Member, Institute of Advanced Study, Princeton. 2005–2013 Senior researcher, Physics of Complex Systems, Weizmann Institute. 2000–2004 Fellow, Center for Physics and Biology, Rockefeller University, New York. Host: Prof. Albert Libchaber 1995–2000 Ph.D. in Physics, Weizmann Institute, “Universality in Microemulsions”, Supervisor: Prof. Samuel A. Safran. 1991–1995 M.Sc. in Physics, Weizmann Institute. 1988–1990 B.Sc. in Physics and Mathematics (Talpyot), Hebrew University, Jerusalem. Teaching: Landmark Experiments in Biology (2006); Statistical Physics (2007, 2017-20); Information in Biology (2012); Errors and Codes (IAS, 2012); Theory of Living Matter (2016); Students and post-doctoral fellows (03/2020) Pineros William (postdoc, 2019- ) John Mcbride (postdoc, 2018- ) Somya Mani (postdoc, 2018- ) Tamoghna Das (postdoc, 2018- ) Ashwani Tripathi (postdoc, 2018- ) Sandipan Dutta (postdoc, 2016-2021), Prof. at BIRS Pileni, India Vladimir Reinharz (postdoc, 2018-2020), Prof. at U. Montreal. YongSeok Jho (research fellow, 2016-2017), Prof. at GyeongSang U. Yoni Savir (Ph.D., 2005-2011) Prof. at Technion. Adam Lampert (Ph.D., 2008-2012) Prof. at U. Arizona. Arbel Tadmor (M.Sc., 2006-2008) researcher at TRON. Maria Rodriguez Martinez (Postdoc, 2007-2009), PI at IBM Zurich Tamar Friedlander (Postdoc, 2009 -2012) Prof. -

Spindle Assembly in Xenopus Egg Extracts

Spindle Assembly in Xenopus Egg Extracts: Respective Roles of Centrosomes and Microtubule Self-Organization Rebecca Heald, Régis Tournebize, Anja Habermann, Eric Karsenti, and Anthony Hyman Cell Biology Program, European Molecular Biology Laboratory, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany Abstract. In Xenopus egg extracts, spindles assembled end–directed translocation of microtubules by cytoplas- around sperm nuclei contain a centrosome at each pole, mic dynein, which tethers centrosomes to spindle poles. while those assembled around chromatin beads do not. However, in the absence of pole formation, microtu- Poles can also form in the absence of chromatin, after bules are still sorted into an antiparallel array around addition of a microtubule stabilizing agent to extracts. mitotic chromatin. Therefore, other activities in addi- Using this system, we have asked (a) how are spindle tion to dynein must contribute to the polarized orienta- poles formed, and (b) how does the nucleation and or- tion of microtubules in spindles. When centrosomes are ganization of microtubules by centrosomes influence present, they provide dominant sites for pole forma- spindle assembly? We have found that poles are mor- tion. Thus, in Xenopus egg extracts, centrosomes are not phologically similar regardless of their origin. In all cases, necessarily required for spindle assembly but can regu- microtubule organization into poles requires minus late the organization of microtubules into a bipolar array. uring cell division, the correct organization of mi- and Lloyd, 1994). In the absence of centrosomes, bipolar crotubules in bipolar spindles is necessary to dis- spindle assembly seems to occur through the self-organiza- D tribute chromosomes to the daughter cells. The tion of microtubules around mitotic chromatin (McKim slow growing or minus ends of the microtubules are fo- and Hawley, 1995; Heald et al., 1996; Waters and Salmon, cused at each pole, while the plus ends interact with the 1997). -

Intracellular Scaling Mechanisms

Downloaded from http://cshperspectives.cshlp.org/ on September 29, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Intracellular Scaling Mechanisms Simone Reber1,2 and Nathan W. Goehring3 1Max Planck Institute of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology, 01307 Dresden, Germany 2Integrative Research Institute (IRI) for the Life Sciences, Humboldt-Universita¨t zu Berlin, 10115 Berlin, Germany 3MRC Laboratory of Molecular Cell Biology, University College London, WC1E 6BT London, United Kingdom Correspondence: [email protected] Organelle function is often directly related to organelle size. However, it is not necessarily absolute size but the organelle-to-cell-size ratio that is critical. Larger cells generally have increased metabolic demands, must segregate DNA over larger distances, and require larger cytokinetic rings to divide. Thus, organelles often must scale to the size of the cell. The need for scaling is particularly acute during early development during which cell size can change rapidly. Here, we highlight scaling mechanisms for cellular structures as diverse as centro- somes, nuclei, and the mitotic spindle, and distinguish them from more general mechanisms of size control. In some cases, scaling is a consequence of the underlying mechanism of organelle size control. In others, size-control mechanisms are not obviously related to cell size, implying that scaling results indirectly from cell-size-dependent regulation of size- control mechanisms. cell is a highly organized unit in which We also know that cell size can vary dra- Afunctions are compartmentalized into spe- matically even within one organism. Xenopus cific organelles. Each cellular organelle carries laevis is an extreme example. The smallest so- out a distinct function, which is not only related matic cells are only a few micrometers in diam- to its molecular composition but, in many cas- eter, whereas the oocyte and one-cell embryo es, also to its size. -

Causal Queries from Observational Data in Biological Systems Via Bayesian Networks: an Empirical Study in Small Networks

Causal Queries from Observational Data in Biological Systems via Bayesian Networks: An Empirical Study in Small Networks Alex White and Matthieu Vignes Abstract Biological networks are a very convenient modelling and visualisation tool to discover knowledge from modern high-throughput genomics and post- genomics data sets. Indeed, biological entities are not isolated, but are components of complex multi-level systems. We go one step further and advocate for the con- sideration of causal representations of the interactions in living systems. We present the causal formalism and bring it out in the context of biological networks, when the data is observational. We also discuss its ability to decipher the causal infor- mation flow as observed in gene expression. We also illustrate our exploration by experiments on small simulated networks as well as on a real biological data set. Key words: Causal biological networks, Gene regulatory network reconstruction, Direct Acyclic Graph inference, Bayesian networks 1 Introduction Throughout their lifetime, organisms express their genetic program, i.e. the instruc- tion manual for molecular actions in every cell. The products of the expression of this program are messenger RNA (mRNA); the blueprints to produce proteins, the cornerstones of the living world. The diversity of shapes and the fate of cells is a re- sult of different readings of the genetic material, probably because of environmental factors, but also because of epigenetic organisational capacities. The genetic mate- rial appears regulated to produce what the organism needs in a specific situation. We now have access to rich genomics data sets. We see them as instantaneous images of cell activity from varied angles, through different filters. -

Multiscale Modeling in Systems Biology

Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 2051 Multiscale Modeling in Systems Biology Methods and Perspectives ADRIEN COULIER ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS ISSN 1651-6214 ISBN 978-91-513-1225-5 UPPSALA URN urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-442412 2021 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in 2446 ITC, Lägerhyddsvägen 2, Uppsala, Friday, 10 September 2021 at 10:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Professor Mark Chaplain (University of St Andrews). Abstract Coulier, A. 2021. Multiscale Modeling in Systems Biology. Methods and Perspectives. Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 2051. 60 pp. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-513-1225-5. In the last decades, mathematical and computational models have become ubiquitous to the field of systems biology. Specifically, the multiscale nature of biological processes makes the design and simulation of such models challenging. In this thesis we offer a perspective on available methods to study and simulate such models and how they can be combined to handle biological processes evolving at different scales. The contribution of this thesis is threefold. First, we introduce Orchestral, a multiscale modular framework to simulate multicellular models. By decoupling intracellular chemical kinetics, cell-cell signaling, and cellular mechanics by means of operator-splitting, it is able to combine existing software into one massively parallel simulation. Its modular structure makes it easy to replace its components, e.g. to adjust the level of modeling details. We demonstrate the scalability of our framework on both high performance clusters and in a cloud environment. -

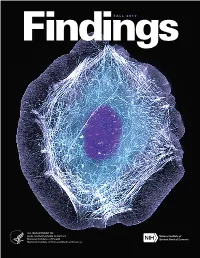

Findings Magazine

FindingsFALL 2017 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medical Sciences features 1 Protein Paradox: Enrique De La Cruz Aims to Understand Actin 18 The Science of Size: Rebecca Heald Explores Size Control in Amphibians articles 5 A World Without Pain 6 Demystifying General Anesthetics 10 There’s an “Ome” for That —TORSTEN WITTMANN, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN FRANCISCO ON THE COVER This human skin cell was bathed 17 Lighting Up the Promise of Gene Therapy in a liquid containing a growth factor. The procedure for Glaucoma triggered the formation of specialized protein structures that enable the cell to move. We depend on our cells 24 NIGMS Is on Instagram! being able to move for basic functions such as the healing of wounds and the launch of immune responses. departments 3 Cool Tools: High-Resolution Microscopy— Editor In Living Color Chris Palmer 9 Spotlight on Videos: Scientists in Action Contributing Writers Carolyn Beans 14 S potlight on the Cell: The Extracellular Matrix, Kathryn Calkins Emily Carlson a Multitasking Marvel Alisa Zapp Machalek Chris Palmer Erin Ross Ruchi Shah activities Production Manager 22 Superstars of Science Quiz Susan Athey Online Editor The Last Word (inside back cover) Susan Athey Find Us At Image credits: Unless otherwise credited, images are royalty-free stock images. https://twitter.com/nigms https://www.facebook.com/nigms.nih.gov Produced by the Offce of Communications and Public Liaison https://www.instagram.com/nigms_nih National Institute of General Medical Sciences National Institutes of Health https://www.youtube.com/user/NIGMS U.S. -

Advancing a Systems Cell-Free Metabolic Engineering Approach to Natural Product Synthesis and Discovery

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2020 Advancing a systems cell-free metabolic engineering approach to natural product synthesis and discovery Benjamin Mohr University of Tennessee Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Mohr, Benjamin, "Advancing a systems cell-free metabolic engineering approach to natural product synthesis and discovery. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2020. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/6837 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Benjamin Mohr entitled "Advancing a systems cell-free metabolic engineering approach to natural product synthesis and discovery." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Energy Science and Engineering. Mitchel Doktycz, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Jennifer Morrell-Falvey, Dale Pelletier, Michael Simpson, Robert Hettich Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Advancing a systems cell-free metabolic engineering approach to natural product synthesis and discovery A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Benjamin Pintz Mohr December 2019 c by Benjamin Pintz Mohr, 2019 All Rights Reserved. -

Bioengineering Professor Trey Ideker Wins 2009 Overton Prize

Bioengineering Professor Trey Ideker Wins 2009 Overton Prize March 13, 2009 Daniel Kane University of California, San Diego bioengineering professor Trey Ideker-a network and systems biology pioneer-has won the International Society for Computational Biology's Overton Prize. The Overton prize is awarded each year to an early-to-mid-career scientist who has already made a significant contribution to the field of computational biology. Trey Ideker is an Associate Professor of Bioengineering at UC San Diego's Jacobs School of Engineering, Adjunct Professor of Computer Science, and member of the Moores UCSD Cancer Center. He is a pioneer in using genome-scale measurements to construct network models of cellular processes and disease. His recent research activities include development of software and algorithms for protein network analysis, network-level comparison of pathogens, and genome-scale models of the response to DNA-damaging agents. "Receiving this award is a wonderful honor and helps to confirm that the work we have been doing for the past several years has been useful to people," said Ideker. "This award also provides great recognition to UC San Diego which has fantastic bioinformatics programs both at the undergraduate and graduate level. I could never have done it without the help of some really first-rate bioinformatics and bioengineering graduate students," said Ideker. Ideker is on the faculty of the Jacobs School of Engineering's Department of Bioengineering, which ranks 2nd in the nationfor biomedical engineering, according to the latest US News rankings. The bioengineering department has ranked among the top five programs in the nation every year for the past decade. -

The Myth of Junk DNA

The Myth of Junk DNA JoATN h A N W ells s eattle Discovery Institute Press 2011 Description According to a number of leading proponents of Darwin’s theory, “junk DNA”—the non-protein coding portion of DNA—provides decisive evidence for Darwinian evolution and against intelligent design, since an intelligent designer would presumably not have filled our genome with so much garbage. But in this provocative book, biologist Jonathan Wells exposes the claim that most of the genome is little more than junk as an anti-scientific myth that ignores the evidence, impedes research, and is based more on theological speculation than good science. Copyright Notice Copyright © 2011 by Jonathan Wells. All Rights Reserved. Publisher’s Note This book is part of a series published by the Center for Science & Culture at Discovery Institute in Seattle. Previous books include The Deniable Darwin by David Berlinski, In the Beginning and Other Essays on Intelligent Design by Granville Sewell, God and Evolution: Protestants, Catholics, and Jews Explore Darwin’s Challenge to Faith, edited by Jay Richards, and Darwin’s Conservatives: The Misguided Questby John G. West. Library Cataloging Data The Myth of Junk DNA by Jonathan Wells (1942– ) Illustrations by Ray Braun 174 pages, 6 x 9 x 0.4 inches & 0.6 lb, 229 x 152 x 10 mm. & 0.26 kg Library of Congress Control Number: 2011925471 BISAC: SCI029000 SCIENCE / Life Sciences / Genetics & Genomics BISAC: SCI027000 SCIENCE / Life Sciences / Evolution ISBN-13: 978-1-9365990-0-4 (paperback) Publisher Information Discovery Institute Press, 208 Columbia Street, Seattle, WA 98104 Internet: http://www.discoveryinstitutepress.com/ Published in the United States of America on acid-free paper. -

Snapshot: Network Motifs Oren Shoval and Uri Alon Department of Molecular Cell Biology, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 76100, Israel

SnapShot: Network Motifs Oren Shoval and Uri Alon Department of Molecular Cell Biology, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 76100, Israel 326 Cell 143, October 15, 2010 ©2010 Elsevier Inc. DOI 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.050 See online version for legend and references. SnapShot: Network Motifs Oren Shoval and Uri Alon Department of Molecular Cell Biology, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 76100, Israel Transcription regulation and signaling networks are composed of recurring patterns called network motifs. Network motifs are much more prevalent in biological networks than would be expected by comparison to random networks and comprise almost the entire network structure. The same small set of network motifs has been found in diverse organ- isms ranging from bacteria to plants to humans. Experiments show that each network motif can carry out specific dynamic functions in the computation done by the cell. Here we review the main classes of network motifs and their biological functions. Autoregulation Negative autoregulation (NAR) occurs when a transcription factor represses the transcription of its own gene. (We use transcription to help make examples concrete; all circuits described here could operate also in other regulatory modes, e.g., a protein inhibiting its own activity by autophosphorylation.) This occurs in about half of the repressors in E. coli and can speed up the response time of gene circuits and reduce cell–cell variation in protein levels that are due to fluctuations in production rate. Positive autoregulation occurs when a transcription factor enhances its own rate of production. Response times are slowed and variation is usually enhanced. This motif, given sufficient cooperativity, can lead to bimodal (all-or-none) distributions, where the concentration of X is low in some cells but high in others. -

A Lab Co-Op Helps Young Faculty Members to Thrive

WORLD VIEW A personal take on events A lab co-op helps young MARK JOSEPH HANSON faculty members to thrive Linking a lab with others fosters crucial camaraderie, collaboration and productivity, writes Rebecca Heald. hen I started my lab at the University of California, Berkeley, form the group. Proximity is key. I advise postdocs who want to follow two decades ago, what terrified me most was the thought that conventional paths in academia to prioritize jobs in departments that I alone was responsible for everything — from formulating are hiring lots of junior faculty members, and to avoid institutions — Wsuccessful PhD-thesis projects to picking the right freezer. Fortunately, even prestigious ones — that force assistant professors to compete with my stress was mitigated because, within a year, two new assistant profes- each other. That makes everyone in the lab miserable. sors, Matt Welch and Karsten Weis, were hired and given lab space next Matt, Karsten and I had each previously experienced collaborative to mine. Although we all focused on different areas of cell biology, we environments — Matt at the University of California, San Francisco; me shared common interests and values and quickly saw benefits in joining at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Heidelberg, Germany; forces. We called our joint groups the Trilab. and Karsten at both — which helped us conceive of the Trilab. We were Matt, Karsten and I saved space by sharing chemical and microscopy exceedingly fortunate to be at the same career stage at the same place and rooms, and saved money by pooling equipment. We even tore down a time. -

Microtubules: 50 Years on from the Discovery of Tubulin

PERSPECTIVES microtubule dynamics and organization VIEWPOINT emerge from a defined set of proteins Microtubules: 50 years on from through reconstitution experiments. Jonathon Howard. One of the big questions back when I got into the microtubule the discovery of tubulin business, around 1990, was how motor proteins such as kinesin and dynein use Gary Borisy, Rebecca Heald, Jonathon Howard, Carsten Janke, ATP hydrolysis to generate force for Andrea Musacchio and Eva Nogales transport along microtubules (such as axonal transport) or for cell motility (such as Abstract | Next year will be the 50th anniversary of the discovery of tubulin. ciliary or flagellar motion). The interaction To celebrate this discovery, six leaders in the field of microtubule research reflect of kinesin with microtubules was a model on key findings and technological breakthroughs over the past five decades, system, because it was clear that only a discuss implications for therapeutic applications and provide their thoughts on relatively small number of kinesins must what questions need to be addressed in the near future. be capable of moving small vesicles along microtubules. A related question was how microtubule growth and shrinkage could Identifying the main component of Rebecca Heald. In the mid-1990s, one generate force to move chromosomes microtubules was obviously the pressing question was why microtubules during mitosis. Polymerization and pressing task in the field around 50 years ago. in cells were so much more dynamic than depolymerization forces were very What key questions were being pursued microtubules assembled from purified mysterious: how could you hold on to the when you entered the arena of tubulin.