Billy Cobham Ever Disappeared Completely from the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE SHARED INFLUENCES and CHARACTERISTICS of JAZZ FUSION and PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014

COMMON GROUND: THE SHARED INFLUENCES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF JAZZ FUSION AND PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master in Jazz Performance and Pedagogy Department of Music 2020 Abstract Blunk, Joseph Michael (M.M., Jazz Performance and Pedagogy) Common Ground: The Shared Influences and Characteristics of Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock Thesis directed by Dr. John Gunther In the late 1960s through the 1970s, two new genres of music emerged: jazz fusion and progressive rock. Though typically thought of as two distinct styles, both share common influences and stylistic characteristics. This thesis examines the emergence of both genres, identifies stylistic traits and influences, and analyzes the artistic output of eight different groups: Return to Forever, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Miles Davis’s electric ensembles, Tony Williams Lifetime, Yes, King Crimson, Gentle Giant, and Soft Machine. Through qualitative listenings of each group’s musical output, comparisons between genres or groups focus on instances of one genre crossing over into the other. Though many examples of crossing over are identified, the examples used do not necessitate the creation of a new genre label, nor do they demonstrate the need for both genres to be combined into one. iii Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Part One: The Emergence of Jazz………………………………………………………….. 3 Part Two: The Emergence of Progressive………………………………………………….. 10 Part Three: Musical Crossings Between Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock…………….... 16 Part Four: Conclusion, Genre Boundaries and Commonalities……………………………. 40 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………. -

Michael Brecker Chronology

Michael Brecker Chronology Compiled by David Demsey • 1949/March 29 - Born, Phladelphia, PA; raised in Cheltenham, PA; brother Randy, sister Emily is pianist. Their father was an attorney who was a pianist and jazz enthusiast/fan • ca. 1958 – started studies on alto saxophone and clarinet • 1963 – switched to tenor saxophone in high school • 1966/Summer – attended Ramblerny Summer Music Camp, recorded Ramblerny 66 [First Recording], member of big band led by Phil Woods; band also contained Richie Cole, Roger Rosenberg, Rick Chamberlain, Holly Near. In a touch football game the day before the final concert, quarterback Phil Woods broke Mike’s finger with the winning touchdown pass; he played the concert with taped-up fingers. • 1966/November 11 – attended John Coltrane concert at Temple University; mentioned in numerous sources as a life-changing experience • 1967/June – graduated from Cheltenham High School • 1967-68 – at Indiana University for three semesters[?] • n.d. – First steady gigs r&b keyboard/organist Edwin Birdsong (no known recordings exist of this period) • 1968/March 8-9 – Indiana University Jazz Septet (aka “Mrs. Seamon’s Sound Band”) performs at Notre Dame Jazz Festival; is favored to win, but is disqualified from the finals for playing rock music. • 1968 – Recorded Score with Randy Brecker [1st commercial recording] • 1969 – age 20, moved to New York City • 1969 – appeared on Randy Brecker album Score, his first commercial release • 1970 – co-founder of jazz-rock band Dreams with Randy, trombonist Barry Rogers, drummer Billy Cobham, bassist Doug Lubahn. Recorded Dreams. Miles Davis attended some gigs prior to recording Jack Johnson. -

PASIC 2010 Program

201 PASIC November 10–13 • Indianapolis, IN PROGRAM PAS President’s Welcome 4 Special Thanks 6 Area Map and Restaurant Guide 8 Convention Center Map 10 Exhibitors by Name 12 Exhibit Hall Map 13 Exhibitors by Category 14 Exhibitor Company Descriptions 18 Artist Sponsors 34 Wednesday, November 10 Schedule of Events 42 Thursday, November 11 Schedule of Events 44 Friday, November 12 Schedule of Events 48 Saturday, November 13 Schedule of Events 52 Artists and Clinicians Bios 56 History of the Percussive Arts Society 90 PAS 2010 Awards 94 PASIC 2010 Advertisers 96 PAS President’s Welcome elcome 2010). On Friday (November 12, 2010) at Ten Drum Art Percussion Group from Wback to 1 P.M., Richard Cooke will lead a presen- Taiwan. This short presentation cer- Indianapolis tation on the acquisition and restora- emony provides us with an opportu- and our 35th tion of “Old Granddad,” Lou Harrison’s nity to honor and appreciate the hard Percussive unique gamelan that will include a short working people in our Society. Arts Society performance of this remarkable instru- This year’s PAS Hall of Fame recipi- International ment now on display in the plaza. Then, ents, Stanley Leonard, Walter Rosen- Convention! on Saturday (November 13, 2010) at berger and Jack DeJohnette will be We can now 1 P.M., PAS Historian James Strain will inducted on Friday evening at our Hall call Indy our home as we have dig into the PAS instrument collection of Fame Celebration. How exciting to settled nicely into our museum, office and showcase several rare and special add these great musicians to our very and convention space. -

Ebook / John Mclaughlin and the Mahavishnu Orchestra

RCRGU0FGTS \\ John McLaughlin and the Mahavishnu Orchestra: Score Edition, Score (Paperback) » eBook Joh n McLaugh lin and th e Mah avish nu Orch estra: Score Edition, Score (Paperback) By Professor of Land Studies John McLaughlin Alfred Music, 2007. Paperback. Condition: New. Language: English . Brand New Book. John McLaughlin and the Mahavishnu Orchestra was the most influential band of the 1970s fusion jazz movement. Fresh from turning the jazz world upside down on Miles Davis immortal In a Silent Way, John McLaughlin teamed with Jan Hammer, Rick Laird, Billy Cobham, and Jerry Goodman to form the Mahavishnu Orchestra, an amazing fusion of jazz, blues, rock and Indian music. This book contains John s own miniature scores to 28 classic Mahavishnu songs. Titles: A Lotus on Irish Streams * Awakening * Be Happy * Birds of Fire * Celestial Terrestrial * Commuters * Dawn * Dream * Earth Ship * Eternity s Breath * Faith * Hope * If I Could See * Lila s Dance * Meeting of the Spirits * Miles Beyond * Noonward Race * On the Way Home to Earth * One Word * Open Country Joy * Opus I * Pastoral * Resolution * Sanctuary * Sapphire Bullets of Pure Love * The Dance of Maya * Thousand Island Park * Vital Transformation * You Know, You Know. READ ONLINE [ 1.53 MB ] Reviews It is an amazing ebook i actually have at any time study. We have read and so i am certain that i will likely to read through yet again once again later on. Your way of life period will likely be change when you complete looking at this pdf. -- Cristina Rowe Extremely helpful to all class of individuals. It really is writter in straightforward terms instead of diicult to understand. -

Jerry Goodman (Chicago, Illinois, March 16, 1949) Is an American Violinist Best Known for Playing Electric Violin in the Bands T

Jerry Goodman (Chicago, Illinois, March 16, 1949) is an American violinist best known for playing electric violin in the bands The Flock and the jazz fusion Mahavishnu Orchestra. Goodman actually began his musical career as The Flock's roadie before joining the band on violin. Trained in the conservatory, both of his parents were in the string section of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. His uncle was the noted composer and jazz pianist Marty Rubenstein. After his 1970 appearance on John McLaughlin's album My Goal's Beyond, he became a member of McLaughlin's original Mahavishnu Orchestra lineup until the band broke up in 1973, and was viewed as a soloist of equal virtuosity to McLaughlin, keyboardist Jan Hammer and drummer Billy Cobham. In 1975, after Mahavishnu, Goodman recorded the album Like Children with Mahavishnu keyboard alumnus Jan Hammer. Starting in 1985 he recorded three solo albums for Private Music -- On the Future of Aviation, Ariel, and the live album It's Alive with luminaries such as Fred Simon and Jim Hines—and went on tour with his own band, as well as with Shadowfax and The Dixie Dregs. He scored Lily Tomlin's The Search for Signs of Intelligent Life in the Universe and is the featured violinist on numerous film soundtracks, including Billy Crystal's Mr. Saturday Night and Steve Martin's Dirty Rotten Scoundrels . His violin can be heard on more than fifty albums from artists ranging from Toots Thielemans to Hall & Oates to Styx to Jordan Rudess to Choking Ghost to Derek Sherinian. Goodman has appeared on four of Sherinian's solo records - Inertia (2001), Black Utopia (2003), Mythology (2004), and Blood of the Snake (2006) In 1993, Goodman joined the American instrumental band, The Dixie Dregs, fronted by guitarist Steve Morse. -

Muni 20081106

MUNI 20081106 JAZZ ROCK, FUSION… 01 Ballet (Mike Gibbs) 4:55 Gary Burton Quartet : Gary Burton-vibes; Larry Coryell-g; Steve Swallow-b; Roy Haynes-dr. New York, April 18, 1967. RCA LSP-3835. 02 It’s All Becoming So Clear Now (Mike Mainieri) 5:25 Mike Mainieri -vib; Jeremy Steig-fl; Joe Beck-elg; Sam Brown-elg,acg; Warren Bernhardt-p,org; Hal Gaylor-b; Chuck Rainey-elb; Donald MacDonald-dr. Published 1969. Solid State SS 18049. 03 Little Church (Miles Davis) 3:17 Miles Davis -tp; Steve Grossman-ss; Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock-elp; Keith Jarrett-org; John McLaughlin-g; Dave Holland-b,elb; Jack DeJohnette-dr; Airto Moreira-perc; Hermeto Pascoal-dr,whistling,voc,elp. New York, June 4, 1970. Columbia C2K 65135. 04 Medley: Gemini (Miles Davis) /Double Image (Joe Zawinul) 5:56 Miles Davis -tp; Wayne Shorter-ss; Joe Zawinul, Chick Corea-elp; John McLaughlin-g; Dave Holland-b; Khalil Balakrishna-sitar; Billy Cobham, Jack DeJohnette-dr; Airto Moreira-perc. New York, February 6, 1970. Columbia C2K 65135. 05 Milky Way (Wayne Shorter-Joe Zawinul) 2:33 06 Umbrellas (Miroslav Vitouš-W. Shorter-J. Zawinul) 3:26 Weather Report : Wayne Shorter -ss,ts; Miroslav Vitouš-b; Joe Zawinul -p,kb; Alphonse Mouzon-dr; Airto Moreira-perc. 1971. Columbia 468212 2. 07 Birds of Fire (John McLaughlin) 5:39 Mahavishnu Orchestra : John McLaughlin -g; Jerry Goodman-vio; Jan Hammer-kb,Moog syn; Rick Laird-b; Billy Cobham-dr. New York, 1973. Columbia KC 31996. 08 La Fiesta (Chick Corea) 7:49 Return to Forever : Joe Farrell-ss; Chick Corea -elp; Stanley Clarke-b; Airto Moreira-dr,perc; Flora Purim-perc. -

January 1992

VOLUME 16, NUMBER 1 FEATURES MEMPHIS DRUMMERS MIAMI SOUND MACHINE'S Though this southern city is ROBERT RODRIGUEZ experiencing a musical renais- MARK sance these days, newcomers & RAFAEL PADILLA might be surprised by some of BRZEZICKI the bands responsible for that Much of the credit for MSM's huge rebirth. In this special report, MD His work as an in-demand ses- success goes to its burning checks in with some local drum- sion player in England, as well Latin/pop rhythms. The messen- mers who are pushing as his landmark performances gers of that hot stuff are drummer the new Memphis with Big Country, Pete Rodriguez and percussionist sounds way past the Townshend, and the Cult, proved 30 Padilla. In this special story, MD city limits. Mark Brzezicki was one of the pokes its nose into the Sound • by Robert Santelli strongest drum voices of the Machine's kitchen and discovers past decade. The '90s look to be some of the secret as busy and exciting: In this recipes of their success. INSIDE exclusive interview, Mark dis- • by Robyn Flans cusses his new work with Procul 26 VIC FIRTH Harum, Big Country, and old crony Simon Townshend. A peek behind the scenes of one 20 of the industry's top drumstick • by Simon Goodwin makers—and at its dynamic namesake. • by Rick Van Horn 34 MD's YAMAHA DRUM RIG GIVEAWAY Your second chance to win a Yamaha Drum Rig worth 64 $12,400! COVER PHOTO BY EDMOND WALLACE COLUMNS Education 52 ROCK CHARTS Neil Peart: "Where's Equipment My Thing?" TRANSCRIBED BY JEFF WALD 40 PRODUCT CLOSE-UP 66 HEAD TALK Drum Workshop Departments -

Indian Music Integrates Every Dimension of the Human Psyche ORCHESTRA to REMEMBER

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2012 ISSUE MMUSICMAG.COM SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2012 ISSUE MMUSICMAG.COM MUSICIAN Is there a theme guiding the album? he was doing. But the Beatles were doing TOOLS OF THE TRADE Not at all. The music just came. But each it, and the Beach Boys, too—we were all piece has an anecdote behind it. The looking for answers to these profound opening piece, “Trancefusion,” is from my existential questions: Who am I? What does John McLaughlin played some of his favorite old hippie days, my trance days. Even it all mean? What is this thing called God? guitars on Now Here This including one he today, when I meditate, I go into another The big questions of life. That was tied with received as a gift from PRS owner Paul state of consciousness that some would my musical search. It took me a long time. Reed Smith. “It’s a standard model with call a trance. Trance is not a bad word, and Some people get it younger and quicker, McCarty pickups and a whammy bar, and is fusion is a label that’s been put on me for but not me. The whole of the ’60s was really a wonderful instrument,” he says. the last 40 years. But I like the real word research and work. “There are two pieces on the new transfusion, too. It’s a healthy word. When album where I play MIDI through a Godin you put fresh blood into someone, you make Miles Davis named a song after you. Freeway, which has the new wireless MIDI them feel better. -

47955 the Musician's Lifeline INT01-192 PRINT REV INT03 08.06.19.Indd

181 Our Contributors Carl Allen: jazz drummer, educator Brian Andres: drummer, educator David Arnay: jazz pianist, composer, educator at University of Southern California Kenny Aronoff: live and studio rock drummer, author Rosa Avila: drummer Jim Babor: percussionist, Los Angeles Philharmonic, educator at University of Southern California Jennifer Barnes: vocalist, arranger, educator at University of North Texas Bob Barry: (jazz) photographer John Beasley: jazz pianist, studio musician, composer, music director John Beck: percussionist, educator (Eastman School of Music, now retired) Bob Becker: xylophone virtuoso, percussionist, composer Shelly Berg: jazz pianist, dean of Frost Music School at University of Miami Chuck Berghofer: jazz bassist, studio musician Julie Berghofer: harpist Charles Bernstein: film composer Ignacio Berroa: Cuban drummer, educator, author Charlie Bisharat: violinist, studio musician Gregg Bissonette: drummer, author, voice-over actor Hal Blaine: legendary studio drummer (Wrecking Crew fame) Bob Breithaupt: drummer, percussionist, educator at Capital University Bruce Broughton: composer, EMMY Chris Brubeck: bassist, bass trombonist, composer Gary Burton: vibes player, educator (Berklee College of Music, now retired), GRAMMY 182 THE MUSICIAN’S LIFELINE Jorge Calandrelli: composer, arranger, GRAMMY Dan Carlin: award-winning engineer, educator at University of Southern California Terri Lyne Carrington: drummer, educator at Berklee College of Music, GRAMMY Ed Carroll: trumpeter, educator at California Institute of -

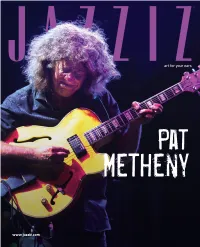

JAZZIZ-Metheny-Interviews.Pdf

Pat Metheny www.jazziz.com JAZZIZ Subscription Ad Lage.pdf 1 3/21/18 10:32 AM Pat Metheny Covered Though I was a Pat Metheny fan for nearly a decade before I special edition, so go ahead and make fun if you please). launched JAZZIZ in 1983, it was his concert, at an outdoor band In 1985, we published a cover story that included Metheny, shell on the University of Florida campus, less than a year but the feature was about the growing use of guitar synthesizers before, that got me to focus on the magazine’s mission. in jazz, and we ran a photo of John McLaughlin on the cover. As a music reviewer for several publications in the late Strike two. The first JAZZIZ cover that featured Pat ran a few ’70s and early ’80s, I was in touch with ECM, the label for years later, when he recorded Song X with Ornette Coleman. whom Metheny recorded. It was ECM that sent me the press When the time came to design the cover, only photos of Metheny credentials that allowed me to go backstage to interview alone worked, and Pat was unhappy with that because he felt Metheny after the show. By then, Metheny had recorded Ornette should have shared the spotlight. Strike three. C around 10 LPs with various instrumental lineups: solo guitar, A few years later, I commissioned Rolling Stone M duo work with Lyles Mays on the chart-topping As Wichita Fall, photographer Deborah Feingold to do a Metheny shoot for a Y So Falls Wichita Falls, trio, larger ensembles and of course his Pat cover story that would delve into his latest album at the time. -

Tesisw: Tecnología Midi: Análisis De Esta Tecnología

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO FACULTAD DE INGENIERÍA TECNOLOGÍA MIDI: ANÁLISIS DE ESTA TECNOLOGÍA PARA SU ADAPTACIÓN A LA GUITARRA ELÉCTRICA TESIS Que para obtener el título de Ingeniero en Computación P R E S E N T A Sergio Emiliano Duque Vega DIRECTOR DE TESIS M.C. Alejandro Velázquez Mena Ciudad Universitaria, Cd. Mx., 2017 UNAM – Dirección General de Bibliotecas Tesis Digitales Restricciones de uso DERECHOS RESERVADOS © PROHIBIDA SU REPRODUCCIÓN TOTAL O PARCIAL Todo el material contenido en esta tesis esta protegido por la Ley Federal del Derecho de Autor (LFDA) de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (México). El uso de imágenes, fragmentos de videos, y demás material que sea objeto de protección de los derechos de autor, será exclusivamente para fines educativos e informativos y deberá citar la fuente donde la obtuvo mencionando el autor o autores. Cualquier uso distinto como el lucro, reproducción, edición o modificación, será perseguido y sancionado por el respectivo titular de los Derechos de Autor. Tecnología MIDI Sergio Emiliano Duque Vega Agradecimientos Al Alfa y Omega, principio y fin de todo, por regalarme el don de la música y permitirme escuchar. Todo viene de ti y todo vuelve a ti. A mi madre y a mi padre, Susana y Sergio, por creer en la educación como una puerta que transforma la vida de quienes decidimos pasar a través de ella. Sin su apoyo y orientación no hubiese sido posible realizar este trabajo. A mis hermanas, Michel y Paola, por siempre ofrecerme su ayuda, ejemplo y amistad. A mi cuñado y sobrino, Carlos y Carlitos, por traer nueva alegría y música a nuestra familia. -

Zakir Hussain & Masters of Percussion

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS Sunday, March 23, 2014, 7pm Zellerbach Hall Zakir Hussain & Masters of Percussion with Zakir Hussain tabla Selvaganesh Vinayakram kanjira & ghatam Steve Smith Western drums Niladri Kumar sitar Dilshad Khan sarangi Deepak Bhatt dhol Vijay Chavan dholki and special guest Antonia Minnecola Kathak dancer PROGRAM Tonight’s program will be announced from the stage. There will be one intermission. Cal Performances’ – season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. PLAYBILL ABOUT THE ARTISTS The foremost disciple of his father, the leg- endary Ustad Allarakha, Mr. Hussain was a child prodigy who began his professional career at the age of twelve and had toured internation- ally with great success by the age of 18. He has been the recipient of many awards, grants and honors, including Padma Bhushan (2002), Padma Shri (1988), the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award (1991), Kalidas Samman (2006), the 1999 National Heritage Fellowship Award, the Bay Area Isadora Duncan Award (1998–1999), and Grammy Awards in 1991 and 2009 for Best World Music Album for Planet Drum and Global Drum Project, both collaborations with Mickey Hart. His music and extraordinary con- tribution to the music world were honored in April 2009, with four widely heralded and sold- out concerts in Carnegie Hall’s “Perspectives” series. Also in 2009, Mr. Hussain was named a Susana Millman Susana Member in the Order of Arts and Letters by AKIR HUSSAIN (tabla) is today appreciated France’s Ministry of Culture and Commun - Zboth in the field of percussion and in the ication. Most recently, the National Symphony music world at large as an international phe- Orchestra with Christoph Eschenbach com- nomenon.