Three New Pupfish Species, Cyprinodon (Teleostei, Cyprinodontidae), from Chihuahua, México, and Arizona, USA Author(S): W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edna Assay Development

Environmental DNA assays available for species detection via qPCR analysis at the U.S.D.A Forest Service National Genomics Center for Wildlife and Fish Conservation (NGC). Asterisks indicate the assay was designed at the NGC. This list was last updated in June 2021 and is subject to change. Please contact [email protected] with questions. Family Species Common name Ready for use? Mustelidae Martes americana, Martes caurina American and Pacific marten* Y Castoridae Castor canadensis American beaver Y Ranidae Lithobates catesbeianus American bullfrog Y Cinclidae Cinclus mexicanus American dipper* N Anguillidae Anguilla rostrata American eel Y Soricidae Sorex palustris American water shrew* N Salmonidae Oncorhynchus clarkii ssp Any cutthroat trout* N Petromyzontidae Lampetra spp. Any Lampetra* Y Salmonidae Salmonidae Any salmonid* Y Cottidae Cottidae Any sculpin* Y Salmonidae Thymallus arcticus Arctic grayling* Y Cyrenidae Corbicula fluminea Asian clam* N Salmonidae Salmo salar Atlantic Salmon Y Lymnaeidae Radix auricularia Big-eared radix* N Cyprinidae Mylopharyngodon piceus Black carp N Ictaluridae Ameiurus melas Black Bullhead* N Catostomidae Cycleptus elongatus Blue Sucker* N Cichlidae Oreochromis aureus Blue tilapia* N Catostomidae Catostomus discobolus Bluehead sucker* N Catostomidae Catostomus virescens Bluehead sucker* Y Felidae Lynx rufus Bobcat* Y Hylidae Pseudocris maculata Boreal chorus frog N Hydrocharitaceae Egeria densa Brazilian elodea N Salmonidae Salvelinus fontinalis Brook trout* Y Colubridae Boiga irregularis Brown tree snake* -

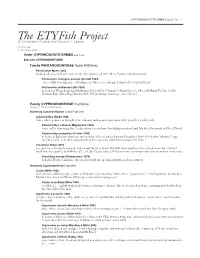

The Etyfish Project © Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J

CYPRINODONTIFORMES (part 3) · 1 The ETYFish Project © Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J. Lazara COMMENTS: v. 3.0 - 13 Nov. 2020 Order CYPRINODONTIFORMES (part 3 of 4) Suborder CYPRINODONTOIDEI Family PANTANODONTIDAE Spine Killifishes Pantanodon Myers 1955 pan(tos), all; ano-, without; odon, tooth, referring to lack of teeth in P. podoxys (=stuhlmanni) Pantanodon madagascariensis (Arnoult 1963) -ensis, suffix denoting place: Madagascar, where it is endemic [extinct due to habitat loss] Pantanodon stuhlmanni (Ahl 1924) in honor of Franz Ludwig Stuhlmann (1863-1928), German Colonial Service, who, with Emin Pascha, led the German East Africa Expedition (1889-1892), during which type was collected Family CYPRINODONTIDAE Pupfishes 10 genera · 112 species/subspecies Subfamily Cubanichthyinae Island Pupfishes Cubanichthys Hubbs 1926 Cuba, where genus was thought to be endemic until generic placement of C. pengelleyi; ichthys, fish Cubanichthys cubensis (Eigenmann 1903) -ensis, suffix denoting place: Cuba, where it is endemic (including mainland and Isla de la Juventud, or Isle of Pines) Cubanichthys pengelleyi (Fowler 1939) in honor of Jamaican physician and medical officer Charles Edward Pengelley (1888-1966), who “obtained” type specimens and “sent interesting details of his experience with them as aquarium fishes” Yssolebias Huber 2012 yssos, javelin, referring to elongate and narrow dorsal and anal fins with sharp borders; lebias, Greek name for a kind of small fish, first applied to killifishes (“Les Lebias”) by Cuvier (1816) and now a -

Monitoring and Understanding Toxic Cyanobacteria and Cochlodinium Polykrikoides Blooms in Suffolk County

MONITORING AND UNDERSTANDING TOXIC CYANOBACTERIA AND COCHLODINIUM POLYKRIKOIDES BLOOMS IN SUFFOLK COUNTY A FINAL REPORT BY CHRISTOPHER J. GOBLER, STONY BROOK UNIVERSITY SUBMITTED SEPTEMBER 2013 REVISED MAY 2014 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS: Executive Summary……………………………………………………………pages 3- 6 Task 1. – Literature and Regulatory Review…………………………………pages 7 - 14 Task 2. –Summer monitoring of freshwater bathing beach lakes in Suffolk County. Suffolk County Bathing Beaches………………………………….…………pages 15 - 16 Task 3. Seasonal monitoring the most toxic lakes in Suffolk County…..……pages 17 - 25 Task 4. Cyanotoxin findings and final report………………………...…………..pages 26 Task 5 & 6. Assess the ability of Cochlodinium polykrikoides to form cysts; Quantify the production and densities of Cochlodinium polykrikoides cysts before, during and after blooms………………………………………………………………..………pages 27 - 57 Task 7. Assess the temperature tolerance of Cochlodinium polykrikoides….pages 58 - 61 Task 8. Assess the mechanism of toxicity of Cochlodinium polykrikoides....pages 62 - 93 Task 9. Explore the vulnerability of Suffolk County fish populations to Cochlodinium polykrikoides………………………………………………………...………pages 94 - 113 Task 10. Prepare a final report regarding Cochlodinium polykrikoides results….pages 114 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This project, Monitoring and Understanding Toxic Cyanobacteria and Cochlodinium polykrikoides Blooms in Suffolk County, was funded by Suffolk County Capital Project 8224, Harmful Algal Blooms, and was initiated to address ongoing blooms of toxic cyanobacteria and Cochlodinium polykrikoides in Suffolk County waters. Cyanobacteria Cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green algae, are microscopic organisms found in both marine and fresh water environments. Under favorable conditions of sunlight, temperature, and nutrient concentrations, cyanobacteria can form massive blooms that discolor the water and often result in a scums and floating mats on the water’s surface. -

Endangered Species

FEATURE: ENDANGERED SPECIES Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater and Diadromous Fishes ABSTRACT: This is the third compilation of imperiled (i.e., endangered, threatened, vulnerable) plus extinct freshwater and diadromous fishes of North America prepared by the American Fisheries Society’s Endangered Species Committee. Since the last revision in 1989, imperilment of inland fishes has increased substantially. This list includes 700 extant taxa representing 133 genera and 36 families, a 92% increase over the 364 listed in 1989. The increase reflects the addition of distinct populations, previously non-imperiled fishes, and recently described or discovered taxa. Approximately 39% of described fish species of the continent are imperiled. There are 230 vulnerable, 190 threatened, and 280 endangered extant taxa, and 61 taxa presumed extinct or extirpated from nature. Of those that were imperiled in 1989, most (89%) are the same or worse in conservation status; only 6% have improved in status, and 5% were delisted for various reasons. Habitat degradation and nonindigenous species are the main threats to at-risk fishes, many of which are restricted to small ranges. Documenting the diversity and status of rare fishes is a critical step in identifying and implementing appropriate actions necessary for their protection and management. Howard L. Jelks, Frank McCormick, Stephen J. Walsh, Joseph S. Nelson, Noel M. Burkhead, Steven P. Platania, Salvador Contreras-Balderas, Brady A. Porter, Edmundo Díaz-Pardo, Claude B. Renaud, Dean A. Hendrickson, Juan Jacobo Schmitter-Soto, John Lyons, Eric B. Taylor, and Nicholas E. Mandrak, Melvin L. Warren, Jr. Jelks, Walsh, and Burkhead are research McCormick is a biologist with the biologists with the U.S. -

Relation of Desert Pupfish Abundance to Selected Environmental Variables

Environmental Biology of Fishes (2005) 73: 97–107 Ó Springer 2005 Relation of desert pupfish abundance to selected environmental variables in natural and manmade habitats in the Salton Sea basin Barbara A. Martin & Michael K. Saiki U.S. Geological Survey, Biological Resources Division, Western Fisheries Research Center-Dixon Duty Station, 6924 Tremont Road, Dixon, CA 95620, U.S.A. (e-mail: [email protected]) Received 6 April 2004 Accepted 12 October 2004 Key words: species assemblages, predation, water quality, habitat requirements, ecological interactions, endangered species Synopsis We assessed the relation between abundance of desert pupfish, Cyprinodon macularius, and selected biological and physicochemical variables in natural and manmade habitats within the Salton Sea Basin. Field sampling in a natural tributary, Salt Creek, and three agricultural drains captured eight species including pupfish (1.1% of the total catch), the only native species encountered. According to Bray– Curtis resemblance functions, fish species assemblages differed mostly between Salt Creek and the drains (i.e., the three drains had relatively similar species assemblages). Pupfish numbers and environmental variables varied among sites and sample periods. Canonical correlation showed that pupfish abundance was positively correlated with abundance of western mosquitofish, Gambusia affinis, and negatively correlated with abundance of porthole livebearers, Poeciliopsis gracilis, tilapias (Sarotherodon mossambica and Tilapia zillii), longjaw mudsuckers, Gillichthys mirabilis, and mollies (Poecilia latipinna and Poecilia mexicana). In addition, pupfish abundance was positively correlated with cover, pH, and salinity, and negatively correlated with sediment factor (a measure of sediment grain size) and dissolved oxygen. Pupfish abundance was generally highest in habitats where water quality extremes (especially high pH and salinity, and low dissolved oxygen) seemingly limited the occurrence of nonnative fishes. -

Distribution of Amargosa River Pupfish (Cyprinodon Nevadensis Amargosae) in Death Valley National Park, CA

California Fish and Game 103(3): 91-95; 2017 Distribution of Amargosa River pupfish (Cyprinodon nevadensis amargosae) in Death Valley National Park, CA KRISTEN G. HUMPHREY, JAMIE B. LEAVITT, WESLEY J. GOLDSMITH, BRIAN R. KESNER, AND PAUL C. MARSH* Native Fish Lab at Marsh & Associates, LLC, 5016 South Ash Avenue, Suite 108, Tempe, AZ 85282, USA (KGH, JBL, WJG, BRK, PCM). *correspondent: [email protected] Key words: Amargosa River pupfish, Death Valley National Park, distribution, endangered species, monitoring, intermittent streams, range ________________________________________________________________________ Amargosa River pupfish (Cyprinodon nevadensis amargosae), is one of six rec- ognized subspecies of Amargosa pupfish (Miller 1948) and survives in waters embedded in a uniquely harsh environment, the arid and hot Mojave Desert (Jaeger 1957). All are endemic to the Amargosa River basin of southern California and Nevada (Moyle 2002). Differing from other spring-dwelling subspecies of Amargosa pupfish (Cyprinodon ne- vadensis), Amargosa River pupfish is riverine and the most widely distributed, the extent of which has been underrepresented prior to this study (Moyle et al. 2015). Originating on Pahute Mesa, Nye County, Nevada, the Amargosa River flows intermittently, often under- ground, south past the towns of Beatty, Shoshone, and Tecopa and through the Amargosa River Canyon before turning north into Death Valley National Park and terminating at Badwater Basin (Figure 1). Amargosa River pupfish is data deficient with a distribution range that is largely unknown. The species has been documented in Tecopa Bore near Tecopa, Inyo County, CA (Naiman 1976) and in the Amargosa River Canyon, Inyo and San Bernardino Counties, CA (Williams-Deacon et al. -

The Extinction of the Catarina Pupfish Megupsilon Aporus and the Implications for the Conservation of Freshwater Fish in Mexico

The extinction of the Catarina pupfish Megupsilon aporus and the implications for the conservation of freshwater fish in Mexico A RCADIO V ALDÉS G ONZÁLEZ,LOURDES M ARTÍNEZ E STÉVEZ M A .ELENA Á NGELES V ILLEDA and G ERARDO C EBALLOS Abstract Extinctions are occurring at an unprecedented ; Régnier et al., ). Since the start of the st century it rate as a consequence of human activities. Vertebrates con- has become clear that population depletion and extinction stitute the best-known group of animals, and thus the group of both freshwater and marine fishes is a severe and wide- for which there are more accurate estimates of extinctions. spread problem (e.g. Ricciardi & Rasmussen, ; Myers Among them, freshwater fishes are particularly threatened &Worm,; Olden et al., ; Burkhead, ). and many species are declining. Here we report the extinc- Extinction of freshwater fishes has been relatively well tion of an endemic freshwater fish of Mexico, the Catarina documented in North America (e.g. Miller et al., ; pupfish Megupsilon aporus, the sole species of the genus Burkhead, ). A compilation of the conservation status Megupsilon. We present a synopsis of the discovery and de- of freshwater fishes in Mexico has revealed that species scription of the species, the threats to, and degradation of, its have become extinct in the wild or have been extirpated habitat, and the efforts to maintain the species in captivity from the country, and . (% of all species in before it became extinct in . The loss of the Catarina Mexico) are facing extinction (IUCN, ; Ceballos et al., pupfish has evolutionary and ecological implications, and b; Table ). -

Extinction Rates in North American Freshwater Fishes, 1900–2010 Author(S): Noel M

Extinction Rates in North American Freshwater Fishes, 1900–2010 Author(s): Noel M. Burkhead Source: BioScience, 62(9):798-808. 2012. Published By: American Institute of Biological Sciences URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1525/bio.2012.62.9.5 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Articles Extinction Rates in North American Freshwater Fishes, 1900–2010 NOEL M. BURKHEAD Widespread evidence shows that the modern rates of extinction in many plants and animals exceed background rates in the fossil record. In the present article, I investigate this issue with regard to North American freshwater fishes. From 1898 to 2006, 57 taxa became extinct, and three distinct populations were extirpated from the continent. Since 1989, the numbers of extinct North American fishes have increased by 25%. From the end of the nineteenth century to the present, modern extinctions varied by decade but significantly increased after 1950 (post-1950s mean = 7.5 extinct taxa per decade). -

Springs and Springs-Dependent Taxa of the Colorado River Basin, Southwestern North America: Geography, Ecology and Human Impacts

water Article Springs and Springs-Dependent Taxa of the Colorado River Basin, Southwestern North America: Geography, Ecology and Human Impacts Lawrence E. Stevens * , Jeffrey Jenness and Jeri D. Ledbetter Springs Stewardship Institute, Museum of Northern Arizona, 3101 N. Ft. Valley Rd., Flagstaff, AZ 86001, USA; Jeff@SpringStewardship.org (J.J.); [email protected] (J.D.L.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 27 April 2020; Accepted: 12 May 2020; Published: 24 May 2020 Abstract: The Colorado River basin (CRB), the primary water source for southwestern North America, is divided into the 283,384 km2, water-exporting Upper CRB (UCRB) in the Colorado Plateau geologic province, and the 344,440 km2, water-receiving Lower CRB (LCRB) in the Basin and Range geologic province. Long-regarded as a snowmelt-fed river system, approximately half of the river’s baseflow is derived from groundwater, much of it through springs. CRB springs are important for biota, culture, and the economy, but are highly threatened by a wide array of anthropogenic factors. We used existing literature, available databases, and field data to synthesize information on the distribution, ecohydrology, biodiversity, status, and potential socio-economic impacts of 20,872 reported CRB springs in relation to permanent stream distribution, human population growth, and climate change. CRB springs are patchily distributed, with highest density in montane and cliff-dominated landscapes. Mapping data quality is highly variable and many springs remain undocumented. Most CRB springs-influenced habitats are small, with a highly variable mean area of 2200 m2, generating an estimated total springs habitat area of 45.4 km2 (0.007% of the total CRB land area). -

Proceedings of the Desert Fishes Council 2003

Proceedings of the Desert Fishes Council VOLUME XXXV 2003 ANNUAL SYMPOSIUM 16 - 19 November Death Valley California, U.S.A. Edited by Dean A. Hendrickson Texas Natural History Collection University of Texas at Austin 10100 Burnet Road, PRC 176 / R4000 Austin, Texas 78758-4445, U.S.A. and Lloyd T. Findley Centro de Investigación en Alimentación y Desarrollo, A.C.-Unidad Guaymas Carretera al Varadero Nacional Km. 6.6, “Las Playitas” Apartado Postal 284, Guaymas, Sonora 85400, MÉXICO published: online December 1, 2004; in print January 15, 2005 - ISSN 1068-0381 P.O. Box 337 Bishop, California 93515-0337 760-872-8751 Voice & Fax e-mail: [email protected] PROCEEDINGS OF THE DESERT FISHES COUNCIL – VOL.XXXV (2003 SYMPOSIUM) MISSION / MISIÓN The mission of the Desert Fishes Council is to preserve the biological integrity of desert aquatic ecosystems and their associated life forms, to hold symposia to report related research and management endeavors, and to effect rapid dissemination of information concerning activities of the Council and its members . OFFICERS / OFICIALES President: Paul C. Marsh, Arizona State University, School of Life Sciences, P.O Box 874501, Tempe, AZ 85287-4501 Immediate Past President: David Propst, Conservation Services División, New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, Santa Fe, NM 87504 Executive Secretary: E. Phil Pister, P.O. Box 337, Bishop, California 93515-0337 COMMITTEES / COMITÉS Executive Committee: Michael E. Douglas, Anthony A. Echelle (Member-at-Large), Dean A. Hendrickson, Nadine Kanim, Paul C. Marsh, E. Phil Pister, David L. Propst, Jerome Stefferud Areas Coordinator: Nadine Kanim Awards: Astrid Kodric Brown Membership: Jerome Stefferud Proceedings Co-Editors: Lloyd T. -

Morphological Divergence of Native and Recently Established Populations of White Sands Pupfish (Cyprinodon Tularosa) Author(S): Michael L

Morphological Divergence of Native and Recently Established Populations of White Sands Pupfish (Cyprinodon tularosa) Author(s): Michael L. Collyer, James M. Novak, Craig A. Stockwell Source: Copeia, Vol. 2005, No. 1 (Feb. 24, 2005), pp. 1-11 Published by: American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4098615 . Accessed: 13/01/2011 13:16 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=asih. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Copeia. http://www.jstor.org 2005, No. -

Compare and Contrast the Water Environment Between Death Valley Pupfish Specie and Devil’S Hole Pupfish Specie

Compare and Contrast the Water environment between Death Valley Pupfish Specie and Devil’s Hole Pupfish Specie By Roy Tianran Gao 1 Table of Contents Title page 1 Abstract 3 Introduction and Background 3 Water Temperature 4 Salinity 6 Water Level 7 Conservation 10 Conclusion 11 References 12 2 ABSTRACT The two types of pupfish (Cyprinodon) in Death Valley National Park are Death Valley pupfish and Devil’s Hole pupfish. Death Valley pupfish has been existed over 10,000 years and Devil’s Hole pupfish has been existed for over 20,000 years. Both of the pupfishes are endangered species. The average number of Death Valley pupfish has decreased by about 100 since 1990s, and the number of Devil’s Hole pupfish has decreased by 400 since 1995. Comparing the water level, water temperature and the water salinity between the two species of pupfish would help to define the living requirements and reason of decreasing population. The research toward the result is based on 7 journal articles, 4 websites, and 1 book. As the result shows, Death Valley Pupfish and Devil’s Hole Pupfish live in different water environments and functioned differently. Understanding the water environment of the two types of pupfishes will help people building new habitats for pupfishes and increase their population so that would be possible to avoid the extinction of pupfishes from the earth. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND Pupfish is a small killifish in the Southwest of America. There are five pupfish species in Death Valley which are Armargosa pupfish, Saratoga Pupfish, Devil’s Hole pupfish, Death Valley pupfish, and Cotton ball Marsh pupfish (National Park Service, 2008).