The Legality of Dress Codes for Students, Et. Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Word Definitions

PAGE 1 OF 12 WORD DEFINITIONS The Catholic Words Memory Match Card Game, a fun way for the entire family—or classroom— to learn new Catholic vocabulary words! Instilling a love and reverence for the faith should begin at an early age. This game was borne out of my own desire to do just that for my own children. The Catholic Words Memory Match Card Game will provide parents, grandparents, teachers, homeschoolers, Dan Gonzalez, his wife Elisa and their catechists and youth ministers a fun way to help teach Catholic vocabulary words. two children Matthew and Zoe. A FUN WAY TO LEARN Watch your little one’s excitement at Mass when they recognize the vessels, objects and vestments With these free printable definitions, the game used in the liturgy. Introducing these words will cards become flash cards. help prepare them to receive the Sacraments and Show a card and read its definition. Let the inaugurate a lifelong journey of learning about the child see the picture of the real-world object. wonders of their Catholic faith. Discuss where the object is seen at your local May God bless you and those entrusted to your care. parish or in the home. Take the cards with you to church and point out the items before or after Mass. Then, let the games begin! Catholic Words Memory Match is an addictive way to learn new Catholic vocabulary words! Dan Gonzalez Advent Wreath: A wreath usually made Alb: A white robe with long sleeves worn by the Altar Bells: A bell or set of bells rung of holly or evergreen branches that hold three priest under his chasuble and the deacon under immediately after the consecration of each purple candles and a rose one. -

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

Buddhist Monastic Traditions of Southern Asia

BUDDHIST MONASTIC TRADITIONS OF SOUTHERN ASIA dBET Alpha PDF Version © 2017 All Rights Reserved BDK English Tripitaka 93-1 BUDDHIST MONASTIC TRADITIONS OF SOUTHERN ASIA A RECORD OF THE INNER LAW SENT HOME FROM THE SOUTH SEAS by Sramana Yijing Translated from the Chinese (Taishô Volume 54, Number 2125) by Li Rongxi Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research 2000 © 2000 by Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai and Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transcribed in any form or by any means —electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise— without the prior written permission of the publisher. First Printing, 2000 ISBN: 1-886439-09-5 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 98-67122 Published by Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research 2620 Warring Street Berkeley, California 94704 Printed in the United States of America A Message on the Publication of the English Tripit aka The Buddhist canon is said to contain eighty-four thousand different teachings. I believe that this is because the Buddha’s basic approach was to prescribe a different treatment for every spiritual ailment, much as a doctor prescribes a different medicine for every medical ailment. Thus his teachings were always appropriate for the par ticular suffering individual and for the time at which the teaching was given, and over the ages not one of his prescriptions has failed to relieve the suffering to which it was addressed. Ever since the Buddha’s Great Demise over twenty-five hundred years ago, his message of wisdom and compassion has spread through out the world. -

Fashion Jewellery Style Guide

Fashion Jewellery Style Guide 1 About this document Customers today actively visit major e-commerce portals like Amazon to search, seek, compare and consume brand/product information before making a purchase decision. Our goal is to present our selection in a curated and personalized manner such that customers feel like they’re wandering through a mall where their favorite brands are featured but also being able to discover new brands and styles with a boutique-like feel where it’s easy to find anything they’re looking for. The information that you upload to Amazon is displayed on the product detail page and plays a critical role in educate customers to purchase your products. Since Amazon customers are not able to physically pick up or view products when shopping for an item, our goal is to enable the customer to make an informed buying decision by providing as much information as possible on the product detail page. A good detail page is a proven way of driving traffic, product discoverability and online product sales. The below style guide has two components: Data and Imaging .This Style Guide is intended to give you guidance you need to create effective, accurate product detail pages in Jewellery category. Table of Contents Fashion Jewellery Style Guide ...................................................................................................................... 1 About this document ................................................................................................................................... 2 Table of -

Image Prop Quan Tity Information Shout Plastic Megaphone 40X OTS 2 Reds and One Green Disney Maleficient Cameo Purple Hat

Image Prop Quan Information tity Shout Plastic Megaphone 40x OTS 2 Reds and one Green Disney Maleficient Cameo 1 OTS - 35$ Purple Hat Feathers Sequins Mini Top Hat NWT Mardi Gras The Emblem on the front is missing Maroon Karneval Half Mask 1 OTS - 25$ Classic Venetian masquerade style maroon mask with side feathers Vintage 1983 Latex Pig Nose 1 OTS - $ unknown v Mask by Cesar Vintage item from the 1980s Material: latex Geezer Groucho Glasses 1 OTS Slightly Worn out Plastic domino eye mask 5 OTS 2 red, 1 green, 2 black 10 OTS 4 pink, 3 purple, 1 blue 2 green Superhero Sunglasses Fun Express Plastic Swirl 12 OTS $ 6.75 Spin Tops (1 Dozen) Fashion Puppy Tattoos 20 OTS Sporting Goods NewJersey 7 OTS → 4 orange, 3 white Propellers OTS 9 various colors Telescope 7 OTS 3 blue, ,2green, 1red Slide Whistles 6 OTS 3 purple, 3 red, Black Nerdy Plastic Glasses 5 OTS Deputy Sheriff Starr 7 OTS Design Has star in the center Mini Kaleidoscopes 9 OTS ieuwbrK Bouncy balls 5 OTS 2 different green designs, 3 different red designs jar of Jar of Money Bank 1 OTS Boone 64” Eisel 1 OTS White Mirror Pink Umbrella White Battery Operated Closet 4 OTS - 9$ each Tap Light Surfer Dude Wig 1 OTS 13.38$ Forum Novelties Deluxe Santa 1 OTs Claus Wig & Big Set $21.95 1 OTS Sassy Bob $8.99 Neon Purple Wig DELUXE 1 OTS $13.64 INTERNATIONA L BEAUTY BLONDE WIG 1 OTS Jumbo $7.45 Brown Afro Wig Black Braided Hippie Wig 2 OTS - $12.99 Santa Hat 1 OTS Red is sequins by prima creations 1 OTS- 1.95 Patriotic Stove ● Quantity- 1 ● Color- Red, White, Pipe Hat Blue ● Size- 11 Inches -

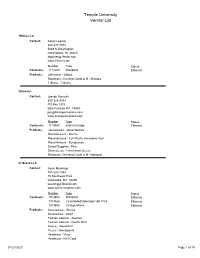

Temple University Vendor List

Temple University Vendor List 19Nine LLC Contact: Aaron Loomer 224-217-7073 5868 N Washington Indianapolis, IN 46220 [email protected] www.19nine.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1112269 Standard Effective Products: Otherwear - Shorts Stationary, Greeting Cards & N - Stickers T-Shirts - T-Shirts 3Click Inc Contact: Joseph Domosh 833-325-4253 PO Box 2315 Bala Cynwyd, PA 19004 [email protected] www.3clickpromotions.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1114550 Internal Usage Effective Products: Housewares - Water Bottles Miscellaneous - Koozie Miscellaneous - Cell Phone Accessory Item Miscellaneous - Sunglasses School Supplies - Pen Short sleeve - t-shirt short sleeve Stationary, Greeting Cards & N - Notepad 47 Brand LLC Contact: Kevin Meisinger 781-320-1384 15 Southwest Park Westwood, MA 02090 [email protected] www.twinsenterprise.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1013854 Standard Effective 1013856 Co-branded/Operation Hat Trick Effective 1013855 Vintage Marks Effective Products: Accessories - Gloves Accessories - Scarf Fashion Apparel - Sweater Fashion Apparel - Rugby Shirt Fleece - Sweatshirt Fleece - Sweatpants Headwear - Visor Headwear - Knit Caps 01/21/2020 Page 1 of 79 Headwear - Baseball Cap Mens/Unisex Socks - Socks Otherwear - Shorts Replica Football - Football Jersey Replica Hockey - Hockey Jersey T-Shirts - T-Shirts Womens Apparel - Womens Sweatpants Womens Apparel - Capris Womens Apparel - Womens Sweatshirt Womens Apparel - Dress Womens Apparel - Sweater 4imprint Inc. Contact: Karla Kohlmann 866-624-3694 101 Commerce -

July Newsletter

July Newsletter A Note From The Oce Summer is in full swing and we are having a blast teaching and learning with our students! We've enjoyed bike day each Thursday and spending extra time outside with the beautiful weather. Our PreK classes have been enjoying a dance class each Wednesday, they had fun painting with Arts on Fire, and they all worked so hard during their basketball camp at the beginning of June! We can't wait to get back to normal and have our families back in the building! A few reminders: we are asking all adults in the building to wear a mask during drop-off and pick-up as our little learners are too young to receive the vaccine. Also, we will be doing "hallway drop-off" and will no longer be using the car pool system. We're excited to have everyone back inside the building where you can see your children in action inside the classroom! Have a great week and stay safe this holiday weekend!! -Peyton and Britt Important Update! We will no longer be asking children to wear masks at school! If you would still like your child to wear one, you are more than welcome to bring them one. Otherwise, no need to worry about bringing them back and forth each day! Staff and parents will still be asked to wear them in the building. As guidelines continue to change, we will keep everyone updated about changes within the school! Important Dates July 5th July 6th July 12th CLOSED in observance of -Welcome back into the We will celebrate National 7- Independence Day building parents! 11 Day with a refreshing -Hours changing to 7am- slushy! 6pm Back To School We are working hard preparing for this coming school year! We will be doing school-wide move-ups on August 2nd. -

Fashion Collection, 1900 - Bulk Dates: 1940-1960

Fashion Collection, 1900 - bulk dates: 1940-1960 Special Collections Department/Long Island Studies Institute Contact Information: Special Collections Department Axinn Library, Room 032 123 Hofstra University Hempstead, NY 11549 Phone: (516) 463-6411, or 463-6404 Fax: (516) 463-6442 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.hofstra.edu/Libraries/SpecialCollections Compiled by: [J. Boucher] Last updated by: Date Completed: [2003] [M. O’Connor] [Aug. 24, 2006] Fashion Collection, 1900 - (bulk dates, 1940-1960) 11 c.f. The Fashion Collection was established by a donation from Eunice Siegelheim and her sister Bernice Wolfson. The core of the collection is 16 hats from the 1930s through the 1950s. The sisters, Eunice and Bernice wore these hats to social events on Long Island. Many were made and purchased in Brooklyn and other parts of New York. The Fashion Collection captures the spirit of various eras with artifacts and illustrations showing how people dressed for various social events. Many of the items in the Fashion Collection correspond to items in other collections, such as photographs from the Image Collection as well as the Long Island History of Sports Collection. Photographs of street scenes in the Image Collection show women of different eras on the sidewalk promenades of Long Island Towns. The Long Island History of Sports Collection includes photographs and programs from Belmont Park’s circa 1910. In addition to the hats, the collection contains other clothing artifacts such as men’s ties, hatboxes, dresses and shoes, from Ms. Siegelheim as well as other donors. The collection also supports fashion research with a run of American Fabrics Magazine, a trade publication that served the garment industry in the 1940s and 1950s. -

Singular/Plural Adjectives This/That/These/Those

067_SBSPLUS1_CH08.qxd 4/30/08 3:22 PM Page 67 Singular/Plural Adjectives This/That/These/Those • Clothing • Price Tags • Colors • Clothing Sizes • Shopping for Clothing • Clothing Ads • Money • Store Receipts VOCABULARY PREVIEW 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 1. shirt 6. jacket 11. pants 2. coat 7. suit 12. jeans 3. dress 8. tie 13. pajamas 4. skirt 9. belt 14. shoes 5. blouse 10. sweater 15. socks 67 068_075_SBSPLUS1_CH08.qxd 5/1/08 5:01 PM Page 68 Clothing 8 2 1 9 3 11 10 4 12 5 6 13 14 7 15 20 21 16 25 24 22 17 26 18 19 23 27 1. shirt 8. earring 15. hat 21. suit 2. tie 9. necklace 16. coat 22. watch 3. jacket 10. blouse 17. glove 23. umbrella 4. belt 11. bracelet 18. purse / 24. sweater 5. pants 12. skirt pocketbook 25. mitten 6. sock 13. briefcase 19. dress 26. jeans 7. shoe 14. stocking 20. glasses 27. boot 68 068_075_SBSPLUS1_CH08.qxd 5/1/08 5:01 PM Page 69 Shirts Are Over There SINGULAR/PLURAL* s z IZ a shirt – shirts a tie – ties a dress – dresses a coat – coats an umbrella – umbrellas a watch – watches a hat – hats a sweater – sweaters a blouse – blouses a belt – belts a necklace – necklaces A. Excuse me. A. Excuse me. A. Excuse me. I’m looking for a shirt. I’m looking for a tie. I’m looking for a dress. B. Shirts are over there. B. Ties are over there. -

Jewellery Designer Leah Wood on Painting, Polaroids and Life-Changing Parties

EMOTIONAL TIES Jewellery designer LEAH WOOD on painting, Polaroids and life-changing parties As a mum, you always treat your kids and husband. These sunglasses were a present to me because I hadn’t looked after myself for a long time. I spotted them online and thought, ‘They’ll look good on my face!’ This is one of our family’s cameras. My mum [Jo Wood] has a lot of Polaroids of her with my dad and famous actors such as John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd in the 1970s. I love the click, the flash and the instantaneous picture. I was 18 when I met my husband My dad’s mother Jack at a party. I plucked up died when I was the courage to get some young and I punch he was serving cherish this – and that was that! jumper – it’s the We married nearly only thing I have ten years ago from her. She and when I look knitted it for me at my [wide when I was nine gold] wedding so it’s 30 years old. ring it reminds me of those vows. I always remember my dad [Rolling Stones guitarist Ronnie] saying that he wanted to copy his brothers My maternal who were sign When my daughter Maggie grandmother painters and [eight] came home from was a doll maker. When she played guitar, school with this picture, I said, passed away, I asked my and now he inspires ‘Holy cow, that’s really good! mum if I could have this doll. me. I painted a portrait Picasso would be overjoyed I love her fishnet tights, of Vivienne Westwood recently, but I if he saw it. -

Aloha Hat Protect Delicate Infant Skin from the Sun’S Harsh Rays

2019 The Monterey, see page 6. The 2019 Collection THE “W” COLLECTION ............................................. 4 WOMEN ..................................................................... 24 PETITE ......................................................................... 42 EXTRAS ....................................................................... 43 MEN ............................................................................. 44 CHILDREN .................................................................. 54 Because life is meant Look for our sun icon throughout to be lived in color! the catalog to determine which hats are UPF 50+. These When we started Wallaroo 19 years ago, I was sure fabrics block 97.5% of the sun’s of our purpose — to craft sun-protective hats that ultraviolet rays. Please remember, make you look and feel great. Inspired by visits to my a Wallaroo hat only protects the skin husband's family in Australia — where the threat of skin it covers. Safeguard the rest of your body cancer has long been understood — I wanted to share by wearing sunglasses and sunscreen. that awareness far and wide. From our home base in Colorado, we draw inspiration The Skin Cancer Foundation from nature — the earthy tones of the Rocky Mountains recommends the material of every and the brilliant blue of the sunny skies. We focus Wallaroo hat with a UPF rating and on quality craftsmanship and functional, fashionable a 3" brim or wider as an effective designs so your Wallaroo hat can go with you on UV protectant. all your adventures. We want you to get out there — to play, hike, swim and explore — with complete confidence, knowing you're covered in style. Wallaroo Sun Protection Commitment: We promise that each year we will As a leader in our industry, we also think it's important donate 1% of our profits to skin to look beyond the bottom line. -

Les Coiffures

Semaine 14 – ORTHOGRAPHE ET VOCABULAIRE Les coiffures 1. Trouvez les 30 fautes d’orthographe cachées dans ce teste extrait de la revue Animagine : Louis XIII perdit ses cheveux à trente ans et inaugura le porc port de la perruque. L’usage de ces postiches faits de faux cheveux était fréquent pour les vieillards des classes privilégiées, par contre un jeune noble aurait eu honte de porter cet attribut. Mais ce que le Roi fait devient coutume et la nouvelle coife coiffe royale faite de cheveux artificiels fut adoptée par la Cour. Louis XIV possédait une perruque différente pour chaque occupation de la journée, cette mode perdurat perdura sous Louis XV. Pendant le règne de Louis XVI, toute la bonne société portait perruque et les perruquiers pouvaient vivre heureux. A cette époque, on comptait environ douze cents perruquiers qui tenaient leur privilège(s) de Saint Louis et employaient six mille personnes. La poudre à perruque était un amidon vendu à prix d’or. Les parfumeurs assuraient détenir un extraordinaire secret de fabrication, alors qu’il ne s’agissait que d’un amidon réduis réduit en poudre et passer passé au travers d’un tamis de soie très serrée. Les boutiques de perruques n’étaient pas réputées pour leur hygiène… C’est la révolution de 1789 qui sonna le glas des perruques, le symbole d’une noblesse vieillissante. Alors, l’expression « tête a à perruque » désignait les vieillards obstinés et nostalgiques qui conservaient l’habitude des faux cheveux, et plus généralement toute personne démodée et vieillotte. Il fallut attendre la fin du XIXème siècle pour voir ressurgir resurgir une profession qui avait quasiment disparu(e).