Ancient Andean Headgear: Medium and Measure of Cultural Identity Niki R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

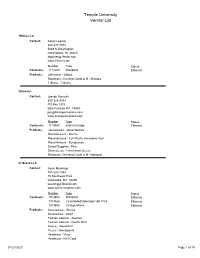

Temple University Vendor List

Temple University Vendor List 19Nine LLC Contact: Aaron Loomer 224-217-7073 5868 N Washington Indianapolis, IN 46220 [email protected] www.19nine.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1112269 Standard Effective Products: Otherwear - Shorts Stationary, Greeting Cards & N - Stickers T-Shirts - T-Shirts 3Click Inc Contact: Joseph Domosh 833-325-4253 PO Box 2315 Bala Cynwyd, PA 19004 [email protected] www.3clickpromotions.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1114550 Internal Usage Effective Products: Housewares - Water Bottles Miscellaneous - Koozie Miscellaneous - Cell Phone Accessory Item Miscellaneous - Sunglasses School Supplies - Pen Short sleeve - t-shirt short sleeve Stationary, Greeting Cards & N - Notepad 47 Brand LLC Contact: Kevin Meisinger 781-320-1384 15 Southwest Park Westwood, MA 02090 [email protected] www.twinsenterprise.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1013854 Standard Effective 1013856 Co-branded/Operation Hat Trick Effective 1013855 Vintage Marks Effective Products: Accessories - Gloves Accessories - Scarf Fashion Apparel - Sweater Fashion Apparel - Rugby Shirt Fleece - Sweatshirt Fleece - Sweatpants Headwear - Visor Headwear - Knit Caps 01/21/2020 Page 1 of 79 Headwear - Baseball Cap Mens/Unisex Socks - Socks Otherwear - Shorts Replica Football - Football Jersey Replica Hockey - Hockey Jersey T-Shirts - T-Shirts Womens Apparel - Womens Sweatpants Womens Apparel - Capris Womens Apparel - Womens Sweatshirt Womens Apparel - Dress Womens Apparel - Sweater 4imprint Inc. Contact: Karla Kohlmann 866-624-3694 101 Commerce -

Fashion Collection, 1900 - Bulk Dates: 1940-1960

Fashion Collection, 1900 - bulk dates: 1940-1960 Special Collections Department/Long Island Studies Institute Contact Information: Special Collections Department Axinn Library, Room 032 123 Hofstra University Hempstead, NY 11549 Phone: (516) 463-6411, or 463-6404 Fax: (516) 463-6442 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.hofstra.edu/Libraries/SpecialCollections Compiled by: [J. Boucher] Last updated by: Date Completed: [2003] [M. O’Connor] [Aug. 24, 2006] Fashion Collection, 1900 - (bulk dates, 1940-1960) 11 c.f. The Fashion Collection was established by a donation from Eunice Siegelheim and her sister Bernice Wolfson. The core of the collection is 16 hats from the 1930s through the 1950s. The sisters, Eunice and Bernice wore these hats to social events on Long Island. Many were made and purchased in Brooklyn and other parts of New York. The Fashion Collection captures the spirit of various eras with artifacts and illustrations showing how people dressed for various social events. Many of the items in the Fashion Collection correspond to items in other collections, such as photographs from the Image Collection as well as the Long Island History of Sports Collection. Photographs of street scenes in the Image Collection show women of different eras on the sidewalk promenades of Long Island Towns. The Long Island History of Sports Collection includes photographs and programs from Belmont Park’s circa 1910. In addition to the hats, the collection contains other clothing artifacts such as men’s ties, hatboxes, dresses and shoes, from Ms. Siegelheim as well as other donors. The collection also supports fashion research with a run of American Fabrics Magazine, a trade publication that served the garment industry in the 1940s and 1950s. -

Les Coiffures

Semaine 14 – ORTHOGRAPHE ET VOCABULAIRE Les coiffures 1. Trouvez les 30 fautes d’orthographe cachées dans ce teste extrait de la revue Animagine : Louis XIII perdit ses cheveux à trente ans et inaugura le porc port de la perruque. L’usage de ces postiches faits de faux cheveux était fréquent pour les vieillards des classes privilégiées, par contre un jeune noble aurait eu honte de porter cet attribut. Mais ce que le Roi fait devient coutume et la nouvelle coife coiffe royale faite de cheveux artificiels fut adoptée par la Cour. Louis XIV possédait une perruque différente pour chaque occupation de la journée, cette mode perdurat perdura sous Louis XV. Pendant le règne de Louis XVI, toute la bonne société portait perruque et les perruquiers pouvaient vivre heureux. A cette époque, on comptait environ douze cents perruquiers qui tenaient leur privilège(s) de Saint Louis et employaient six mille personnes. La poudre à perruque était un amidon vendu à prix d’or. Les parfumeurs assuraient détenir un extraordinaire secret de fabrication, alors qu’il ne s’agissait que d’un amidon réduis réduit en poudre et passer passé au travers d’un tamis de soie très serrée. Les boutiques de perruques n’étaient pas réputées pour leur hygiène… C’est la révolution de 1789 qui sonna le glas des perruques, le symbole d’une noblesse vieillissante. Alors, l’expression « tête a à perruque » désignait les vieillards obstinés et nostalgiques qui conservaient l’habitude des faux cheveux, et plus généralement toute personne démodée et vieillotte. Il fallut attendre la fin du XIXème siècle pour voir ressurgir resurgir une profession qui avait quasiment disparu(e). -

Hats and Headdresses

Hats and Headdresses WN 704 $17.00 WN 701 $10.00 14th-15th Century Hennin Wimple Hat Two styles of Hennin Includes Wimple, Hood, coif, and veil Two styles of Hennin. Popular for a variety of medieval looks. WN 702 $10.00 th th Templer Hat during the 14 and 15 century, Features padded roll with false many noble women shaved their coxcomb, templer back and head so that the Hennin would false liripipe. This hat wear properly. High foreheads reminiscent of medieval Dutch were considered beautiful. Modern headwear. hair can be pulled under the Hennin for a period look. WN 703 $10.00 FF 02 $17.00 Men’s Hats and Caps Headwear Extraordinaire Pattern includes a variety of Contains patterns for 3 bag hats, flat men’s headwear from 14th-16th cap, mob cap, Robin Hood hat, century as shown. PP 52 $22.00 jester’s hood, wizard hat, th Tudor Era Headdresses Renaissance cap, and two 19 A variety of headdresses as century crowned bonnets suitable for pictured covering the time period Dickens event. 1490-1580 AD MR GB $6.00 MR RH $10.00 Glengarry Bonnet Randulf’s The Glengarry is a Scottish MR Coif $4.00 Round Hats bonnet with a military flair. This Randulf's Arming Coif This pattern contains many hats cap is said to have been Sizes: Multisized popular at Renaissance faires and invented by McDonnell of This is a simple pattern for a two- Highland games: flat cap, muffin Glengarry for King George IV’s panel, stretchy, close-fitting hood. It cap, Beret, Tam O’Shanter, 1828 visit to the highlands. -

EC56-409 Hats...Accessories for Dress Gerda Petersen

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Historical Materials from University of Nebraska- Extension Lincoln Extension 1956 EC56-409 Hats...Accessories for Dress Gerda Petersen Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/extensionhist Petersen, Gerda, "EC56-409 Hats...Accessories for Dress" (1956). Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension. 3311. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/extensionhist/3311 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Extension at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1956 E.C. 56·409 llGt:s -T 55 £7 HATS... ty~r.t-~ ,0 ft56 -1-Cf} C. I foriwM I \ UNIVERSITY OF N~!~ENSION SERVICE AND U.S. DEPA~~~~:~~LFE~~:.F AGRICULTURE W COOPERATING CULTURE • V. LAMBERT, DIRECTOR Hats - Accessories For D·res·s Gerda Petersen The most important part of a woman's appearance is her head --her face. her hair. her hat I A hat is more than a protection. It is a frame for the face, a trim for the dress. It is the one mos.t important accessory to a smart appearance. History of Hats All through the centuries the hat has played a varied and at times an amusing role in the history of dress. Caps were worn before hats. It is known that some form of cap was worn as early as 4000 B. C. Among the ancient Egyptians. wigs were worn as a head covering. -

The Legality of Dress Codes for Students, Et. Al

DePaul Law Review Volume 20 Issue 1 1971 Article 4 The Legality of Dress Codes for Students, et. al. James J. Carroll Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review Recommended Citation James J. Carroll, The Legality of Dress Codes for Students, et. al., 20 DePaul L. Rev. 222 (1970) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol20/iss1/4 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Law Review by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENT THE LEGALITY OF DRESS CODES FOR STUDENTS, ET. AL. [N]o scholler doe weare any long lockes of Hayre uppon his haede, but that be polled, notted, or rounded after the accustomed manner of the gravest Schollers of the Universitie. -Excerpt from Cambridge University dress code in 15601 Despite the many changes the philosophy and practice of education have undergone throughout the centuries, at least one element of the learning process has remained constant-the preoccupation of educators with the personal appearance of their pupils. Until recent times, the carte blanche authority of school administrators to prescribe student dress standards was virtually unchallenged. 2 In 1967 the schoolhouse floodgates collapsed;3 the courts suddenly became deluged by a rash of cases brought by students petitioning for review of the legality of their school dress codes. The facts of these cases are remarkably similar. Fact one: DRESS CODE Hair should be neat, clean, and well groomed, and the length should not be over the eye brows, collar or ears. -

The Cultural History of the Corset and Gendered Body in Social and Literary Landscapes

ISSN 2411-9598 (Print) European Journal of September-December 2017 ISSN 2411-4103 (Online) Language and Literature Studies Volume 3 Issue 3 The Cultural History of the Corset and Gendered Body in Social and Literary Landscapes Melis Mulazimoglu Erkal Ege University, Turkey Abstract This study centers on the significance, uses and changes of the corset in the Western culture and literature through a study of body politics, culture and fashion. The emplacement of corsetry in the West as an undergarment goes back to 1600s. Research shows that the study of corsetry is important as the corset has been a permanent, pervasive, popular object preferred mostly by women from different classes, sometimes by men and even children since the Middle Ages. Moreover, it is important to notice how the corset has gone beyond its use value and has become first a symbol of rank and elegance, then of female oppression and victimization and finally a symbol of sexual empowerment and feminine rebellion in contemporary time. Popular critics of the field state that the corset today is far beyond its earlier restrictive usages and negative meanings as the garment today has become a favored item in fashion industry and preferred by celebrity icons all around the world. The corset at present is an outerwear, art object and ideological construct. So, what makes the corset so popular and everlasting? The study on corsetry yields to a critique of Western culture from socio-political perspective as well as through body politics and gender studies. In that respect, this work aims to explore how corsetry in past and contemporary time exists as an essential part of patriarchal ideology, influencing social and literary landscapes and borrowing from the beauty aesthetics, thus creating the idealized feminine of each century. -

United States Army Headgear 1855-1902

lP-'L^ry\'^ ^iT<^ ^V'*^ •'•5v' •^-: v^^i-r .- -' Li-. ''^M^y^- tP-T- United States Army Headgear 1855-1902 . 4^ , <* eP, *T ' * i.'2^-='*".//v; Catalog of United States Army Uniforms in the Collections of the Smithsonian Institution, II 9 3t i^ ;-X- '?^*. '^^^ «y>. .'"'-li. £^^^r M Howell ^mit^nian Iqjtitution United States Army Headgear 1855-1902 Catalog of United States Army Uniforms in the Collections of the Smithsonian Institution, II Edgar M. Howell ^C ; •"• ' I ' h ABSTRACT Howell, Edgar M. United States Army Headgear 1855-1902: Catalog of United States Army Uniforms in the Collections of the Smithsonian Institution, II. Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology, number 30, 109 pages, 63 fig ures, 1975.—This volume brings the story of the evolution of headgear in the United States Regular Army from just prior to the Civil War to the opening of the modern era. Strongly influenced by French, British, and German styles, the U.S. Army tried and found wanting in numerous ways a number of models, and it was not until the adoption of the "drab" campaign hat in the early 1880s that a truly American pattern evolved. The European influence carried on until the 1902 uniform change, and, in the case of the "overseas" cap and chapeau, even beyond. OFFICIAL PUBLICATION DATE is handstamped in a limited number of initial copies and is re corded in the Institution's annual report, Smithsonian Year. SI PRESS NUMBER 5226. COVER DESIGN: "New Regulation Uniform of the United States Artillery" by A. R. Waud (from Harper's Weekly, 8 June 1867). -

The Bonnet and the Beret in Medieval and German Renaissance Art Margit Stadtlober Universität Graz, Österreich

Headscarf and Veiling Glimpses from Sumer to Islam edited by Roswitha Del Fabbro, Frederick Mario Fales, Hannes D. Galter The Bonnet and the Beret in Medieval and German Renaissance Art Margit Stadtlober Universität Graz, Österreich Abstract This paper presents an art-historic contribution, examining the bonnet and the beret as characteristic forms of female and male headdresses and their manifold variations and oriental origins. Both types of head coverings are shaped by sociocul- tural attitudes and evolved in form. Embedded within the wider context of clothing they also, in turn, influence social norms and attitude. Examining their history and genesis also reveals and raises gender-specific perspectives and questions. The depiction and representation of the bonnet and beret during two defining periods in the visual arts, in- corporating role-play and creativity, present a considerable knowledge transfer through media. First instances of gender-specific dress codes can be traced back to the Bible and therefore Paul’s rules for head covering for women in 1 Cor 11,2-16 is intensively debated. The following chapter will trace and illustrate the history of female and male head coverings on the example of various works of art. The strict rules outlined in 1 Corinthian 11 prescribing appropriate head coverings in ceremonial settings, which had a significant and lasting impact, have in time been transformed through the creative freedom afforded by the mundanity of fashion. Keywords Beret. Bonnet. Female Head Covering. Hennin. Veil. Summary 1 Introduction. – 2 From Veil to Bonnet. – 3 The Beret and Dürer’s Caps. 1 Introduction In March 2020, the University of Graz hosted the interdisciplinary Festival Al- pe-Adria dell’Archeologia Pubblica senza Confini on the topic of “Headscarves and veils from the ancient Near East to modern Islam”. -

Vendor List Lehigh University

Vendor List Lehigh University 4imprint, Inc. Karla Kohlmann 866-624-3694 101 Commerce Street Oshkosh, WI 54901 [email protected] www.4imprint.com Contracts: Internal Usage - Effective Standard - Effective Aliases : Bemrose - DBA Nelson Marketing - FKA Products : Accessories - Backpacks Accessories - Convention Bag Accessories - Luggage tags Accessories - purse, change Accessories - Tote Accessories - Travel Bag Gifts & Novelties - Button Gifts & Novelties - Key chains Gifts & Novelties - Koozie Gifts & Novelties - Lanyards Gifts & Novelties - Rally Towel Gifts & Novelties - tire gauge Home & Office - Dry Erase Sheets Home & Office - Fleece Blanket Home & Office - Mug Home & Office - Night Light Paper, Printing, & Publishing - Desk Calendar Paper, Printing, & Publishing - Notepad Paper, Printing, & Publishing - Pen Paper, Printing, & Publishing - Pencil Paper, Printing, & Publishing - Portfolio Specialty Items - Dental Floss Specialty Items - Lip Balm Specialty Items - Massager Specialty Items - Mouse Pad Specialty Items - Sunscreen Sporting Goods & Toys - Balloon Sporting Goods & Toys - Chair-Outdoor Sporting Goods & Toys - Flashlight Sporting Goods & Toys - Frisbee Sporting Goods & Toys - Hula Hoop Sporting Goods & Toys - Pedometer Sporting Goods & Toys - Sports Bottle T-Shirts - T shirt Womens Apparel - Fleece Vest ACCO Brands USA LLC Nan Birdsall 800-323-0500 x5222 101 ONeil Road Sidney, NY 13838 [email protected] 09/21/2016 Page 1 of 71 ACCO Brands USA LLC Nan Birdsall 800-323-0500 x5222 101 ONeil Road Sidney, NY 13838 -

Newsletter Editor: Marlene Robb

ORBOST & DISTRICT HISTORICAL SOCIETY Inc. P.O. BOX 284 ORBOST VIC 3888 President: Heather Terrell Vice President: Marilyn Morgan Secretary: May Leatch Treasurer: Barry Miller Museum Committee: Marina Johnson, Eddie Slatter, Lindsay and Noreen Thomson, Geoff Stevenson, John Phillips Collection Management: Marilyn Morgan, Marlene Robb, May Leatch, Margaret Smith, Barry Miller Research Secretary: Lois Crisp, John Phillips Newsletter Editor: Marlene Robb NEWSLETTER No. 110, August 2014 FROM THE COLLECTION Hats have been around for a very long time. It‘s impossible to say when the first animal skin was pulled over a head as protection against the elements and although this was not a hat in the true sense, it didn’t take long to realize that covering your head could sometimes be an advantage. One of the first hats to be depicted was found in a tomb painting at Thebes and shows a man wearing a coolie-style straw hat. This painting dates back to 3200 BC! Hat-making has existed since the days of old. Millinery, as an art, has through the years, undergone various changes according to trends and cultures. Schools, sports, industrial plants, bureaus of law enforcement, and food preparation industries have now incorporated hats as part of their uniform. Head coverings still remain an essential part of some religions’ protocol as a way of showing respect to their Gods. People also use hats to protect their faces from the hot sun’s rays or in winter to keep the head warm. There were times in the past when hats were considered the most important part of the dress.