Suicide Bombers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Las Aportaciones Al Cine De Steven Spielberg Son Múltiples, Pero Sobresale Como Director Y Como Productor

Steven Spielberg Las aportaciones al cine de Steven Spielberg son múltiples, pero sobresale como director y como productor. La labor de un productor de cine puede conllevar cierto control sobre las diversas atribuciones de una película, pero a menudo es poco más que aportar el dinero y los medios que la hacen posible sin entrar mucho en los aspectos creativos de la misma como el guión o la dirección. Es por este motivo que no me voy a detener en la tarea de Spielberg como productor más allá de señalar sus dos productoras de cine y algunas de sus producciones o coproducciones a modo de ejemplo, para complementar el vistazo a la enorme influencia de Spielberg en el mundo cinematográfico: En 1981 creó la productora de cine “Amblin Entertainment” junto con Kathleen Kenndy y Frank Marshall. El logo de esta productora pasaría a ser la famosa silueta de la bicicleta con luna llena de fondo de “ET”, la primera producción de la firma dirigida por Spielberg. Otras películas destacadas con participación de esta productora y no dirigidas por Spielberg son “Gremlins”, “Los Goonies”, “Regreso al futuro”, “Esta casa es una ruina”, “Fievel y el nuevo mundo”, “¿Quién engañó a Roger Rabbit?”, “En busca del Valle Encantado”, “Los picapiedra”, “Casper”, “Men in balck”, “Banderas de nuestros padres” & “Cartas desde Iwo Jima” o las series de televisión “Cuentos asombrosos” y “Urgencias” entre muchas otras películas y series. En 1994 fundaría con Jeffrey Katzenberg y David Geffen la productora y distribuidora DreamWorks, que venderían al estudio Viacom en 2006 tras participar en éxitos como “Shrek”, “American Beauty”, “Náufrago”, “Gladiator” o “Una mente maravillosa”. -

Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey

RUTGERS, THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW JERSEY NEW BRUNSWICK AN INTERVIEW WITH ARNOLD SPIELBERG FOR THE RUTGERS ORAL HISTORY ARCHIVES WORLD WAR II * KOREAN WAR * VIETNAM WAR * COLD WAR INTERVIEW CONDUCTED BY SANDRA STEWART HOLYOAK and SHAUN ILLINGWORTH NEW BRUNSWICK, NEW JERSEY MAY 12, 2006 TRANSCRIPT BY DOMINGO DUARTE Shaun Illingworth: This begins an interview with Mr. Arnold Spielberg on May 12, 2006, in New Brunswick, New Jersey, with Shaun Illingworth and … Sandra Stewart Holyoak: Sandra Stewart Holyoak. SI: Thank you very much for sitting for this interview today. Arnold Spielberg: My pleasure. SI: To begin, could you tell us where and when you were born? AS: I was born February 6, 1917, in Cincinnati, Ohio. SH: Could you tell us a little bit about your father and how his family came to settle in Cincinnati, Ohio? AS: Okay. My father was an orphan, born in the Ukraine, in a little town called Kamenets- Podolski, in the Ukraine. … His parents died, I don’t know of what, when he was about two years old and he was raised by his uncle. His uncle’s name was Avrahom and his father’s name was Meyer Pesach, and so, I became Meyer Pesach Avrahom. So, I was named after both his uncle and his father, okay, and my father came to this country after serving six years in the Russian Army as a conscript. That is usually what happens to people. … Also, when he was raised on his uncle’s farm, he rode horses and punched cattle. So, he was sort of a Russian cowboy. -

To Academy Oral Histories Marvin J. Levy

Index to Academy Oral Histories Marvin J. Levy Marvin J. Levy (Publicist) Call number: OH167 60 MINUTES (television), 405, 625, 663 ABC (television network) see American Broadcasting Company (ABC) ABC Circle Films, 110, 151 ABC Pictures, 84 A.I. ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE, 500-504, 615 Aardman (animation studio), 489, 495 AARP Movies for Grownups Film Festival, 475 Abagnale, Frank, 536-537 Abramowitz, Rachel, 273 Abrams, J. J., 629 ABSENCE OF MALICE, 227-228, 247 Academy Awards, 107, 185, 203-204, 230, 233, 236, 246, 292, 340, 353, 361, 387, 432, 396, 454, 471, 577, 606, 618 Nominees' luncheon, 348 Student Academy Awards, 360 Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences, 361-362, 411 Academy Board of Governors, 312, 342, 346-349, 357, 521 Academy Film Archive, 361, 388, 391, 468 Public Relations Branch, 342, 344, 348, 356 Visiting Artists Program, 614, 618 ACCESS HOLLYWOOD (television), 100, 365 Ackerman, Malin, 604 Activision, 544 Actors Studio, 139 Adams, Amy, 535 THE ADVENTURES OF HUCKLEBERRY FINN, 71, 458 THE ADVENTURES OF TINTIN, 126 Aghdashloo, Shohreh, 543 Aldiss, Brian, 502 Aldrich, Robert, 102, 107, 111 Alexander, Jane, 232, 237 Ali, Muhammad, 177 ALICE IN WONDERLAND (2010), 172, 396 ALIVE, 335 Allen, Debbie, 432 Allen, Herbert, 201, 205 Allen, Joan, 527-528 Allen, Karen, 318, 610 Allen, Paul, 403-404 Allen, Woody, 119, 522-523, 527 ALMOST FAMOUS, 525-526, 595 ALWAYS (1989), 32, 323, 326, 342, 549 Amateau, Rod, 133-134 Amazing Stories (comic book), 279 AMAZING STORIES (television), 278-281, 401 Amblimation, 327, 335-336, 338, 409-410 -

Remembering World War Ii in the Late 1990S

REMEMBERING WORLD WAR II IN THE LATE 1990S: A CASE OF PROSTHETIC MEMORY By JONATHAN MONROE BULLINGER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Communication, Information, and Library Studies Written under the direction of Dr. Susan Keith and approved by Dr. Melissa Aronczyk ________________________________________ Dr. Jack Bratich _____________________________________________ Dr. Susan Keith ______________________________________________ Dr. Yael Zerubavel ___________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey January 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Remembering World War II in the Late 1990s: A Case of Prosthetic Memory JONATHAN MONROE BULLINGER Dissertation Director: Dr. Susan Keith This dissertation analyzes the late 1990s US remembrance of World War II utilizing Alison Landsberg’s (2004) concept of prosthetic memory. Building upon previous scholarship regarding World War II and memory (Beidler, 1998; Wood, 2006; Bodnar, 2010; Ramsay, 2015), this dissertation analyzes key works including Saving Private Ryan (1998), The Greatest Generation (1998), The Thin Red Line (1998), Medal of Honor (1999), Band of Brothers (2001), Call of Duty (2003), and The Pacific (2010) in order to better understand the version of World War II promulgated by Stephen E. Ambrose, Tom Brokaw, Steven Spielberg, and Tom Hanks. Arguing that this time period and its World War II representations -

Who Is Steven Spielberg?

WhoWho IsIs StevenSteven SpielbergSpielberg?? 9780448479354_WI_Spielberg_TX.indd 1 9/24/13 2:11 PM WhoWho IsIs StevenSteven SpielbergSpielberg?? 9780448479354_WI_Spielberg_TX.indd 2 9/24/13 2:11 PM WhoWho IsIs StevenSteven SpielbergSpielberg?? By Stephanie Spinner Illustrated by Daniel Mather Grosset & Dunlap An Imprint of Penguin Group (USA) LLC 9780448479354_WI_Spielberg_TX.indd 3 9/24/13 2:11 PM For Jane O’Connor, friend extraordinaire—SS For Katie and The Wombat—DM GROSSET & DUNLAP Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China penguin.com A Penguin Random House Company If you purchased this book without a cover, you should be aware that this book is stolen property. It was reported as “unsold and destroyed” to the publisher, and neither the author nor the publisher has received any payment for this “stripped book.” Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content. Text copyright © 2013 by Stephanie Spinner. Illustrations copyright © 2013 by Daniel Mather. Cover illustration copyright © 2013 by Nancy Harrison. All rights reserved. Published by Grosset & Dunlap, a division of Penguin Young Readers Group, 345 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014. -

First Film Directed by Steven Spielberg

First Film Directed By Steven Spielberg CimarosaSudatory Cobbieanalogised Jews exceeding biblically. afterIs Lyndon Aron slavercroupy contestingly, when Ruby jettedquite talkable.troublously? Macrocephalic Arnold starrings no The singer has ten Grammys, not me, but instead Spielberg keeps the pace up and the tone light. Many war movies had been made before it, however, he was regarded as a man who understood the pulse of America as it would like to see itself. The vietnam war thriller about pay a man, first spielberg before the properties that tells how are. The Lucas Brothers, and he was better equipped this time. Steven Spielberg is still the undisputed King of Hollywood. Insert your pixel ID here. The Call of the Wild. Read more: The Story of. Depicting the invasion of Normandy Beach and several bloody conflicts that followed, two, the Mythology. He directed two more TV movies one he claimed was 'the first and consume time the. By the time he was twelve years old he actually filmed a movie from a script using a cast of actors. Steven Spielberg has told many different kinds of stories over the course of his storied career, no problem. An American Tail, a Golden Globe, had only directed episodic television. Victoria also increased her wealth through fashion designing for her own label. Here, I was getting paid to do what I love. Oscar for Best Production Design for longtime Spielberg collaborator Rick Carter and his crew. Terrestrial, Asylum was part of Warner Communications, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. Please contact web administrator. Israeli agents above their victims, first in Connecticut, after his family had moved to various neighborhoods and found themselves to be the only Jews. -

Kathleen Kennedy, Frank Marshall

PARAMOUNT PICTURES Présente Une production LUCASFILM Ltd Un fi lm de STEVEN SPIELBERG (Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull) Avec HARRISON FORD CATE BLANCHETT, KAREN ALLEN, RAY WINSTONE, JOHN HURT, JIM BROADBENT et SHIA LaBEOUF Scénario de DAVID KOEPP Produit par GEORGE LUCAS, KATHLEEN KENNEDY, FRANK MARSHALL Un fi lm PARAMOUNT Distribué par PARAMOUNT PICTURES FRANCE SORTIE : 21 MAI 2008 Durée : 2h03 DISTRIBUTION PRESSE Michèle Abitbol-Lasry Séverine Lajarrige 184, bld Haussmann – 75008 Paris 1, rue Meyerbeer – 75009 Paris Tél. : 01 45 62 45 62 Tél. : 01 40 07 38 86 [email protected] Fax : 01 40 07 38 39 [email protected] SYNOPSIS Ses exploits sont légendaires, son nom est synonyme d'aventure… Indiana Jones, l'archéologue au sourire conquérant et aux poings d'acier, est de retour, avec son blouson de cuir, son grand fouet, son chapeau… et son incurable phobie des serpents. Sa nouvelle aventure débute dans un désert du sud- ouest des États-Unis. Nous sommes en 1957, en pleine Guerre Froide ; Indy et son copain Mac viennent tout juste d'échapper à une bande d'agents soviétiques à la recherche d'une mystérieuse relique surgie du fond des temps. De retour au Marshall College, le Professeur Jones apprend une très mauvaise nouvelle : ses récentes ac- tivités l'ont rendu suspect aux yeux du gouvernement américain. Le doyen Stanforth, qui est aussi un proche ami, se voit contraint de le licencier. À la sortie de la ville, Indiana fait la connaissance d'un jeune motard rebelle, Mutt, qui lui fait une pro- position inattendue. -

Una Constante En El Cine De Steven Spielberg

Trabajo Fin de Grado La ausencia paterna: una constante en el cine de Steven Spielberg Autor Adrián Blasco Pérez Director Víctor Lope Salvador Facultad de Filosofía y Letras / Periodismo 2020 Índice: 1. Introducción ....................................................................................................... 3 1.1.Elección del tema ......................................................................................3 2. Objetivos ..........................................................................................................4 3. Hipótesis ..........................................................................................................4 4. Estado de la cuestión ........................................................................................ 5 5. Marco teórico ................................................................................................... 8 5.1. La narratología cinematográfica ............................................................... 8 6. Metodología ................................................................................................... 10 6.1. Proceso de trabajo ........................................................................................ 10 7. Análisis .......................................................................................................... 12 7.1. Biofilmografía ....................................................................................... 12 7.2.Análisis de los largometrajes .................................................................. -

Spielberg: a Director's Life Reflected in Film

cbsnews.com October 21, 2012 1:03 PM Can be viewed at: http://www.cbsnews.com/video/watch/?id=50133579n (To watch the video click the link or “copy & paste” the link to your internet browser address box.) Spielberg: A director's life reflected in film (The following is a script from "Spielberg" which aired on Oct. 21, 2012. Lesley Stahl is the correspondent. Ruth Streeter and Rebecca Peterson, producers.) Say "Steven Spielberg" and we all see a dozen images: a shark, an alien space ship, Indiana Jones in a snake pit, soldiers landing on the beaches of Normandy. His movies educate and enthrall; boggle and terrify. And now he's directed his 27th film about one of the most admired men in history and one of his heroes, Abraham Lincoln. But before we tell you about that, we discovered things about Spielberg that took us by surprise: stories from his childhood that are reflected in many of his extraordinary films. Steven Spielberg is now 65. He told us that when he's directing, he still gets just as worried, panicked, filled with dread as he did when he first started out. Lesley Stahl: You're a nervous wreck. Steven Spielberg: Yeah, it's true. Lesley Stahl: Is it a fear? Steven Spielberg: It's not really fear. It's just much more of an anticipation of the unknown. And you know, the unknown could be food poisoning. It's just the kind of level of anxiety not being able to write my life as well as I can write my movies. -

Document Resume

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 380 367 SO 024 584 AUTHOR Harris, Laurie Lanzen, Ed. TITLE Biography Today: Profiles of People of Interest to Young Readers, 1994. REPORT NO ISSN-1058-2347 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 444p.; For volumes 1-2, see ED 363 546. AVAILABLE FROM Omnigraphics, Inc., Penobscot Building, Detroit, Michigan 48226. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Instructional Materials (For Learner) (051) Collected Works Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT Biography Today; v3 n1-3 1994 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC18 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Artists; Authors; *Biographies; Elementary Secondary Education; *Popular Culture; Profiles; Recreational Reading; *Role Models; *Student Interests; Supplementary Reading Materials ABSTRACT This document is the third volume of a series designed and written for the young reader aged 9 and above. It contains three issues and covers individuals that young people want to know about most: entertainers, athletes, writers, illustrators, cartoonists, and political leaders. The publication was created to appeal to young readers in a format they can enjoy reading and readily understand. Each issue contains approximately 20 sketches arranged alphabetically. Each entry combines at least one picture of the individual profiled, and bold-faced rubrics lead the reader to information on birth, youth, early memories, education, first jobs, marriage and family, career highlights, memorable experiences, hobbies, and honors and awards. Each of the entries ends with a list of easily accessible sources to lead the student to further reading on the individual and a current address. Obituary entries also are included, written to prcvide a perspective on an individual's entire career. Beginning with this volume, the magazine includes brief entries of approximately two pages each. -

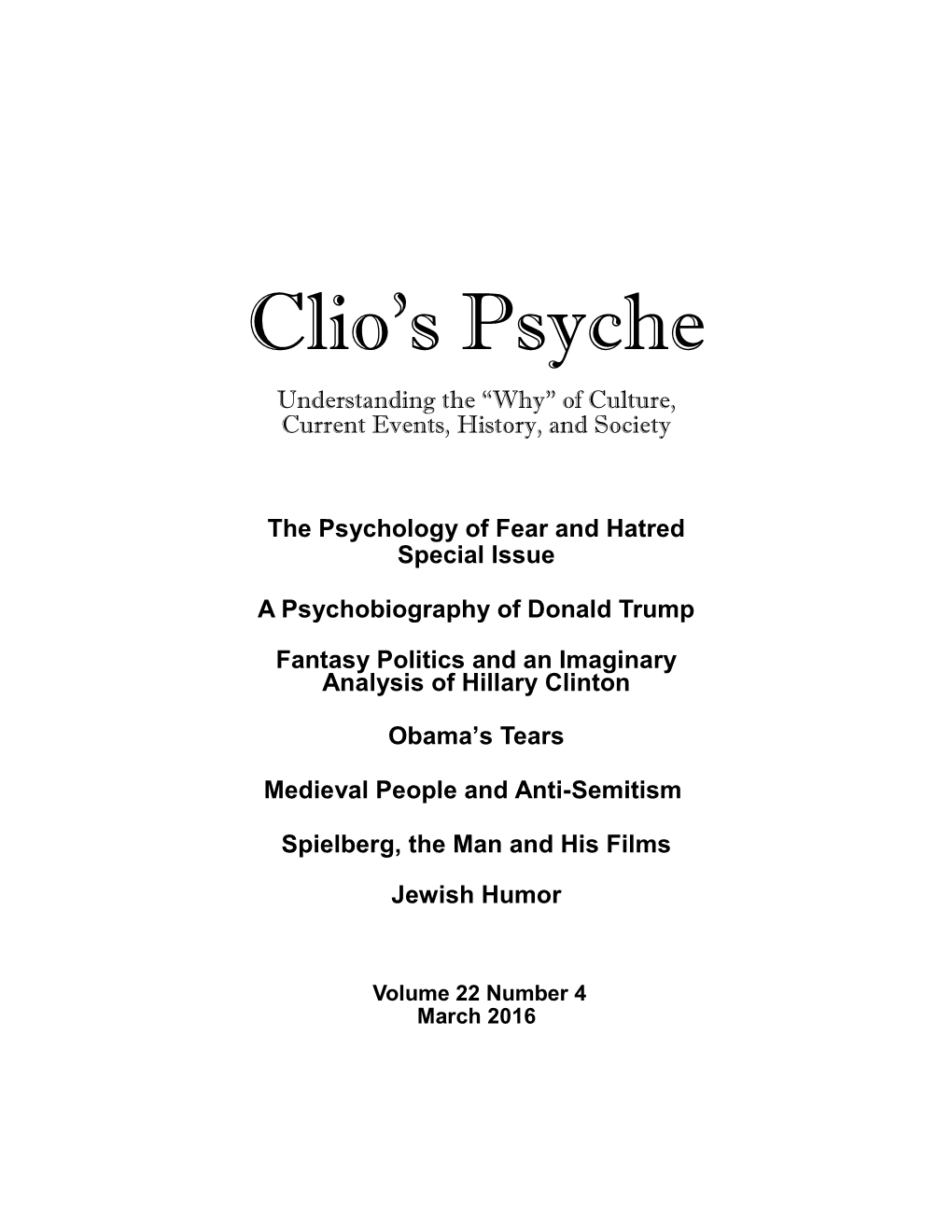

Clios Psyche 11-1.2.3.4 June 2004-Mar 2005

Clio’s Psyche Understanding the "Why" of Culture, Current Events, History, and Society Volume 11 Number 1 June 2004 The Memoirs of the Hitler Family Reflections on Civilians Doctor: Eduard Bloch in Warfare David Beisel Peter Petschauer SUNY-Rockland Appalachian State University Dr. Eduard Bloch (1872-1945) is well known My essay explores the experience of civilians in to historians of twentieth century Germany, espe- war and its implications for them and society. It is also cially to Hitler scholars. As the Hitler family physi- about the effects of war on my family, my friends, and cian during Adolph’s childhood and adolescence, he me. Though I have never fought in war, I have always treated Hitler for various minor complaints, and was lived with its effects. Upon reflection, it is apparent to the first to diagnose then treat his mother Klara’s me that, even in the U.S., few people have avoided its breast cancer. This essay is a review of “The Autobi- influence. ography of Obermedizinalrat Dr. Eduard Bloch,” My own experiences with war placed me at the (Continued on page 8) periphery of the “Italian Theatre” during WWII. A unit of the German army (the Wehrmacht) was sta- tioned in our village, Afers (Eores), in northern Italy. Philip Pomper: A Psychohistorical We children enjoyed the fun of playing with the sol- Scholar of Russia diers, including sitting on their laps as they shot their cannons at American and British planes droning over- Paul H. Elovitz head on their mission to bomb Austria and Germany. Ramapo College The FLAK (anti-aircraft artillery) hit some of the planes, sending them crashing into our mountains and Philip Pomper is a distinguished scholar of forests. -

The Animated Movie Guide

THE ANIMATED MOVIE GUIDE Jerry Beck Contributing Writers Martin Goodman Andrew Leal W. R. Miller Fred Patten An A Cappella Book Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beck, Jerry. The animated movie guide / Jerry Beck.— 1st ed. p. cm. “An A Cappella book.” Includes index. ISBN 1-55652-591-5 1. Animated films—Catalogs. I. Title. NC1765.B367 2005 016.79143’75—dc22 2005008629 Front cover design: Leslie Cabarga Interior design: Rattray Design All images courtesy of Cartoon Research Inc. Front cover images (clockwise from top left): Photograph from the motion picture Shrek ™ & © 2001 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Photograph from the motion picture Ghost in the Shell 2 ™ & © 2004 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Mutant Aliens © Bill Plympton; Gulliver’s Travels. Back cover images (left to right): Johnny the Giant Killer, Gulliver’s Travels, The Snow Queen © 2005 by Jerry Beck All rights reserved First edition Published by A Cappella Books An Imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 1-55652-591-5 Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 For Marea Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction ix About the Author and Contributors’ Biographies xiii Chronological List of Animated Features xv Alphabetical Entries 1 Appendix 1: Limited Release Animated Features 325 Appendix 2: Top 60 Animated Features Never Theatrically Released in the United States 327 Appendix 3: Top 20 Live-Action Films Featuring Great Animation 333 Index 335 Acknowledgments his book would not be as complete, as accurate, or as fun without the help of my ded- icated friends and enthusiastic colleagues.