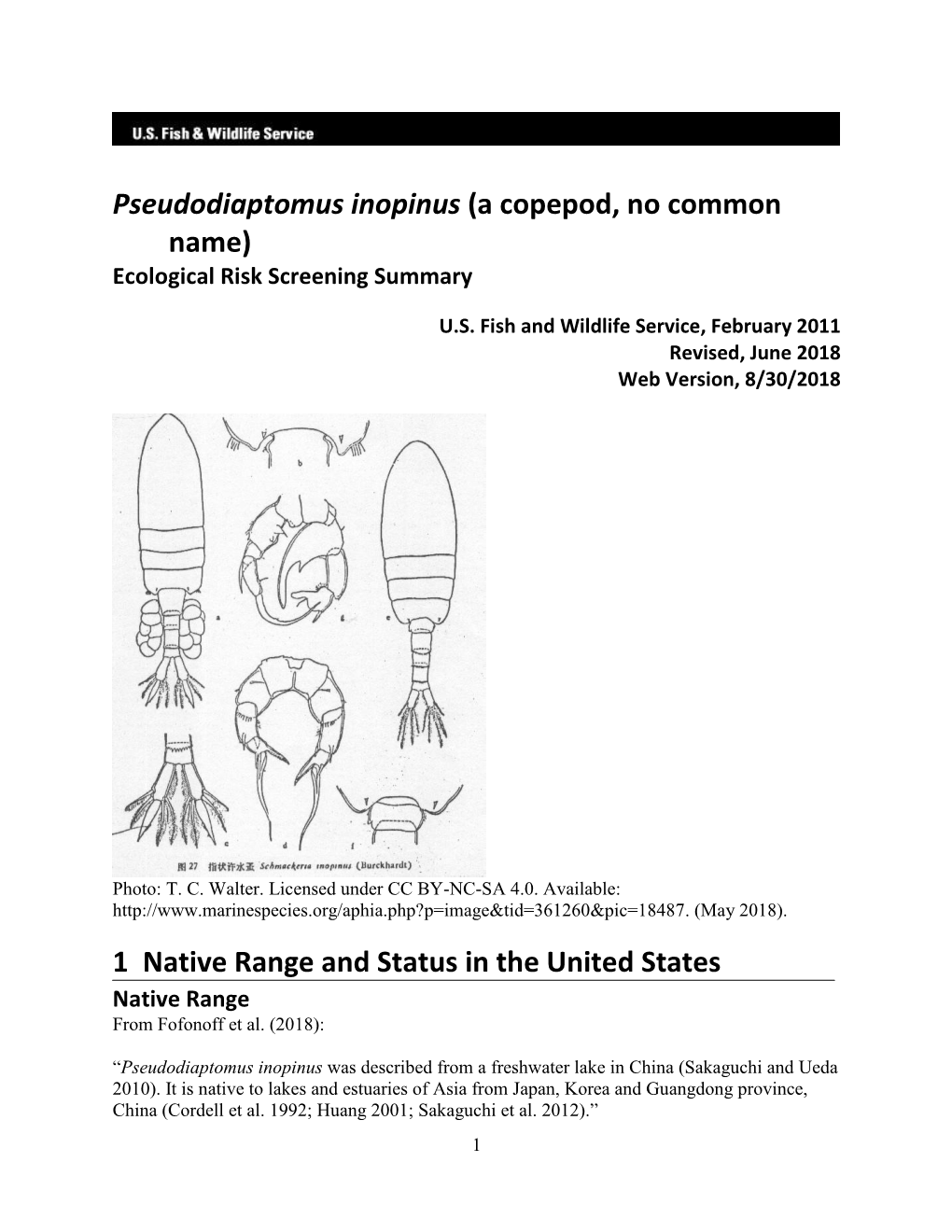

Asian Calanoid Copepod (Pseudodiaptomus Inopinus) ERSS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlas of the Copepods (Class Crustacea: Subclass Copepoda: Orders Calanoida, Cyclopoida, and Harpacticoida)

Taxonomic Atlas of the Copepods (Class Crustacea: Subclass Copepoda: Orders Calanoida, Cyclopoida, and Harpacticoida) Recorded at the Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve and State Nature Preserve, Ohio by Jakob A. Boehler and Kenneth A. Krieger National Center for Water Quality Research Heidelberg University Tiffin, Ohio, USA 44883 August 2012 Atlas of the Copepods, (Class Crustacea: Subclass Copepoda) Recorded at the Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve and State Nature Preserve, Ohio Acknowledgments The authors are grateful for the funding for this project provided by Dr. David Klarer, Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve. We appreciate the critical reviews of a draft of this atlas provided by David Klarer and Dr. Janet Reid. This work was funded under contract to Heidelberg University by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources. This publication was supported in part by Grant Number H50/CCH524266 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve in Ohio is part of the National Estuarine Research Reserve System (NERRS), established by Section 315 of the Coastal Zone Management Act, as amended. Additional information about the system can be obtained from the Estuarine Reserves Division, Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce, 1305 East West Highway – N/ORM5, Silver Spring, MD 20910. Financial support for this publication was provided by a grant under the Federal Coastal Zone Management Act, administered by the Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Silver Spring, MD. -

Salmon Louse Lepeophtheirus Salmonis on Atlantic Salmon

DISEASES OF AQUATIC ORGANISMS Vol. 17: 101-105, 1993 Published November 18 Dis. aquat. Org. Efficacy of ivermectin for control of the salmon louse Lepeophtheirus salmonis on Atlantic salmon 'Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Biological Sciences Branch. Pacific Biological Station, Nanaimo, British Columbia, Canada V9R 5K6 '~epartmentof Zoology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada V6T 2A9 ABSTRACT The eff~cacyof orally administered lveimectin against the common salmon louse Lepeophthelrus salmonls on Atlant~csalmon Salmo salar was invest~gatedunder laboratory condl- tions Both 3 and 6 doses of ivermectln at a targeted dose of 0 05 mg kg-' f~shadmin~stered in the feed every third day airested the development and reduced the Intensity of lnfect~onby L salmon~sThis IS the first report of dn eff~cacioustreatment agd~nstthe chalimus stages of sea lice Ser~oushead dnd doi- sal body lesions, typical of L salmon~sfeed~ng act~vity, which developed on the control f~shwere ab- sent from the ~vermect~n-tredtedf~sh lvermectin fed at these dosage reglmes resulted in a darken~ng of the fish, but appealed not to reduce their feeding activity KEY WORDS Ivermectin Lepeophthe~russalmonis Parasite control Paras~tetreatment - Salmon louse . Salmo salar Sea lice INTRODUCTION dichlorvos into the marine environment, have made the development of alternative treatment methods fol The marine ectoparasitic copepod Lepeophtheirus sea lice a priority salmonis is one of several species of sea lice that Orally administered ivermectln (22,23-Dihydro- commonly infect, and can cause serious disease in, avermectin B,) has been reported to be effective for sea-farmed salmonids (Brandal & Egidius 1979, the control of sea lice and other parasitic copepods on Kabata 1979, 1988, Pike 1989, Wootten et al. -

Hatching Success in the Marine Copepod Pseudocalanus Newmani

Plankton Biol. Ecol. 46 (2): 104-112, 1999 plankton biology & ecology »-• The Plankton Society of Japan I«M9 Deleterious effect of diatom diets on egg production and hatching success in the marine copepod Pseudocalanus newmani Hong-Wu Lee, Syuhei Ban, Yasuhiro Ando, Toru Ota & Tsutomu Ikeda Faculty of Fisheries, Hokkaido University. 3-1-1 Minato-machi. Hakodate. Hokkaido 041-0821. Japan Received 8 October 1998; accepted 25 December 1998 Abstract: Clutch size and hatching success in the marine calanoid copepod Pseudocalanus newmani were examined using two diatom species, Chaetoceros gracilis and Phaeodactylum tricornutum, and two non-diatom species, Pavlova sp. and Heterocapsa triquetra, as food. Both clutch size and hatch ing success varied with food algae after the 3rd clutch. The clutch size was largest with C. gracilis, in termediate with H. triquetra and Pavlova sp., and smallest with Ph. tricornutum. Hatching success was significantly lower with the diatom diets than with the non-diatom ones. With a mixed diet of C. gracilis and Pavlova sp., the clutch size was similar to that with C. gracilis or Pavlova sp. alone, while the hatching success rate was slightly lower than that with Pavlova sp. but higher than that with C. gracilis. Eggs exposed to high concentrations of a C. gracilis extract at 7X107cells ml"1 failed to hatch, but those at the same concentration of Pavlova sp. extract successfully hatched at more than 89%. These results suggest the presence of an anti-mitotic substance in these diatoms. The low hatching success on diatom diets might be due to the presence of as yet unidentified embryogenesis- inhibitory-compounds. -

The Paradox of Diatom-Copepod Interactions*

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 157: 287-293, 1997 Published October 16 Mar Ecol Prog Ser 1 NOTE The paradox of diatom-copepod interactions* Syuhei an', Carolyn ~urns~,Jacques caste13,Yannick Chaudron4, Epaminondas Christou5, Ruben ~scribano~,Serena Fonda Umani7, Stephane ~asparini~,Francisco Guerrero Ruiz8, Monica ~offmeyer~,Adrianna Ianoral0, Hyung-Ku Kang", Mohamed Laabir4,Arnaud Lacoste4, Antonio Miraltolo, Xiuren Ning12, Serge ~oulet~~**,Valeriano ~odriguez'~,Jeffrey Runge14, Junxian Shi12,Michel Starr14,Shin-ichi UyelSf**:Yijun wangi2 'Plankton Laboratory, Faculty of Fisheries. Hokkaido University, Hokkaido, Japan 2~epartmentof Zoology, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand 3Centre dfOceanographie et de Biologie Marine, Arcachon, France 'Station Biologique. CNRS, BP 74. F-29682 Roscoff, France 'National Centre for Marine Research, Institute of Oceanography, Hellinikon, Athens, Greece "niversidad de Antofagasta, Facultad de Recursos del Mar, Instituto de Investigaciones Oceonologicas, Antofagasta, Chile 'Laboratorio di Biologia Marina, University of Trieste, via E. Weiss 1, 1-34127 Trieste. Italy 'Departamento de Biologia Animal Vegetal y Ecologia, Facultad de Ciencias Experimentales, Jaen, Spain '~nstitutoArgentino de Oceanografia. AV. Alem 53. 8000 Bahia Blanca, Argentina 'OStazioneZoologica, Villa comunale 1, 1-80121 Napoli, Italy "Korea Iter-University Institute of Ocean Science. National Fisheries University of Pusan. Pusan. South Korea I2second Institute of Oceanography, State Oceanic Administration, 310012 Hangzhou, -

Reported Siphonostomatoid Copepods Parasitic on Marine Fishes of Southern Africa

REPORTED SIPHONOSTOMATOID COPEPODS PARASITIC ON MARINE FISHES OF SOUTHERN AFRICA BY SUSAN M. DIPPENAAR1) School of Molecular and Life Sciences, University of Limpopo, Private Bag X1106, Sovenga 0727, South Africa ABSTRACT Worldwide there are more than 12000 species of copepods known, of which 4224 are symbiotic. Most of the symbiotic species belong to two orders, Poecilostomatoida (1771 species) and Siphonos- tomatoida (1840 species). The order Siphonostomatoida currently consists of 40 families that are mostly marine and infect invertebrates as well as vertebrates. In a report on the status of the marine biodiversity of South Africa, parasitic invertebrates were highlighted as taxa about which very little is known. A list was compiled of all the records of siphonostomatoids of marine fishes from southern African waters (from northern Angola along the Atlantic Ocean to northern Mozambique along the Indian Ocean, including the west coast of Madagascar and the Mozambique channel). Quite a few controversial reports exist that are discussed. The number of species recorded from southern African waters comprises a mere 9% of the known species. RÉSUMÉ Dans le monde, il y a plus de 12000 espèces de Copépodes connus, dont 4224 sont des symbiotes. La plupart de ces espèces symbiotes appartiennent à deux ordres, les Poecilostomatoida (1771 espèces) et les Siphonostomatoida (1840 espèces). L’ordre des Siphonostomatoida comprend actuellement 40 familles, qui sont pour la plupart marines, et qui infectent des invertébrés aussi bien que des vertébrés. Dans un rapport sur l’état de la biodiversité marine en Afrique du Sud, les invertébrés parasites ont été remarqués comme étant très peu connus. -

Consumption and Growth Rates of Chaetognaths and Copepods in Subtropical Oceanic Waters1

Pacific Science (1978), vol. 32, no. 1 © 1978 by The University Press of Hawaii. All rights reserved Consumption and Growth Rates of Chaetognaths and Copepods in Subtropical Oceanic Waters1 T. K. NEWBURy 2 ABSTRACT: The natural rates of food consumption and growth were cal culated for the chaetognath Pterosagitta draco and the copepod Scolecithrix danae in the Pacific Ocean near Hawaii. The chaetognath's consumption rate was calculated using the observed frequency of food items in the stomachs of large specimens from summer samples and the digestion times from previous publications. The natural consumption rate averaged only one copepod per 24 hr, or about 2 percent of the chaetognath's nitrogen weight per 24 hr. The growth rates of both P. draco and S. danae were calculated with the temporal patterns of variations in the size compositions of the spring populations. The natural growth rates averaged only 2 and 4 percent of the body nitrogen per 24 hr for, respectively, small P. draco and the copepodids of S. danae. These natural rates were low in comparison with published laboratory measurements of radiocarbon accumulation, nitrogen excretion, and oxygen respiration of subtropical oceanic zooplankton. THE RATES OF FOOD CONSUMPTION, metabo concentrations; little growth and poor sur lism, and growth have been determined for vival are obtained in such cultures. Experi zooplankton in some regions of the oceans. ments are usually run with no food or with Temperate and coastal rates have been abundant food, which yield basal rates and described by Mullin (1969), Petipa et al. maximum rates because the rates offunction (1970), and Shushkina et al. -

Chaetognath Eukrohnia Hamata and the Copepod Euchaeta Antarctica in Gerlache Strait, Antarctic Peninsula

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published March 23 Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. ~ Winter population structure and feeding of the chaetognath Eukrohnia hamata and the copepod Euchaeta antarctica in Gerlache Strait, Antarctic Peninsula Vidar Oresland Department of Zoology, Stockholm University, S-106 91 Stockholm. Sweden ABSTRACT: Eukrohnia hamata and Euchaeta antarctica are 2 dominant macrozooplankton predators in the Southern Ocean. Zooplankton san~pleswere taken at 3 stations during July and August 1992, in waters west of the Antarctic Peninsula. E. hamata constituted up to 97 % of all chaetognaths by number and up to 20% of net zooplankton by wet weight. E. hamata breeds at a low intensity and E. antarctica breeds at a high intensity during midwinter. Gut content analyses showed that Metridia gerlachej and the small copepods Oncaea spp. and Microcalanuspygmaeus were the main prey in both species. Esti- mated feeding rates between 0.3 and 0.5 copepods d-' in E. hamata and the number of prey items found in the stomach of E. antarctica (Stages CV and CVI) indicated a feeding intensity during winter that was no less than earlier summer estimates. Rough estimates of daily predation impact showed that E. hamata could eat up to 0.2% of prey standing stock by number. It is suggested that the accumulative predation impact during winter by E. hamata and other carnivorous zooplankton may be large, espe- cially since there was little evidence of prey reproduction that could counteract such a predation impact. About 1 % of the E. hamata population was parasitized or decapitated by a small ectoparasitic polychaete. At 2 stations, 8 and 16% of all E. -

The Salmon Louse Genome: Copepod Features and Parasitic Adaptations

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.15.435234; this version posted March 16, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The salmon louse genome: copepod features and parasitic adaptations. Supplementary files are available here: DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.4600850 Rasmus Skern-Mauritzen§a,1, Ketil Malde*1,2, Christiane Eichner*2, Michael Dondrup*3, Tomasz Furmanek1, Francois Besnier1, Anna Zofia Komisarczuk2, Michael Nuhn4, Sussie Dalvin1, Rolf B. Edvardsen1, Sindre Grotmol2, Egil Karlsbakk2, Paul Kersey4,5, Jong S. Leong6, Kevin A. Glover1, Sigbjørn Lien7, Inge Jonassen3, Ben F. Koop6, and Frank Nilsen§b,1,2. §Corresponding authors: [email protected]§a, [email protected]§b *Equally contributing authors 1Institute of Marine Research, Postboks 1870 Nordnes, 5817 Bergen, Norway 2University of Bergen, Thormøhlens Gate 53, 5006 Bergen, Norway 3Computational Biology Unit, Department of Informatics, University of Bergen 4EMBL-The European Bioinformatics Institute, Wellcome Genome Campus, Hinxton, CB10 1SD, UK 5 Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AE, UK 6 Department of Biology, University of Victoria, Victoria, British Columbia, V8W 3N5, Canada 7 Centre for Integrative Genetics (CIGENE), Department of Animal and Aquacultural Sciences, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Oluf Thesens vei 6, 1433, Ås, Norway 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.15.435234; this version posted March 16, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. -

Fecundity and Survival of the Calanoid Copepod <I>Acartia Tonsa

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Spring 5-2007 Fecundity and Survival of the Calanoid Copepod Acartia tonsa Fed Isochrysis galeana (Tahitian Strain) and Chaetoceros mulleri Angelos Apeitos University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, and the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation Apeitos, Angelos, "Fecundity and Survival of the Calanoid Copepod Acartia tonsa Fed Isochrysis galeana (Tahitian Strain) and Chaetoceros mulleri" (2007). Master's Theses. 276. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/276 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi FECUNDITY AND SURVIVAL OF THE CALANOID COPEPOD ACARTIA TONSA FED ISOCHRYSIS GALEANA (TAHITIAN STRAIN) AND CHAETOCEROS MULLER! by Angelos Apeitos A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of the University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science May2007 ABS1RACT FECUNDITY AND SURVIVAL OF THE CALANOID COPEPOD ACARTIA TONSA FED ISOCHRYSIS GALEANA (TAHITIAN STRAIN) AND CHAETOCEROS MULLER! Historically, red snapper (Lutjanus campechanus) larviculture at the Gulf Coast Research Lab (GCRL) used 25 ppt artificial salt water and mixed, wild zooplankton composed primarily of Acartia tonsa, a calanoid copepod. Acartia tonsa was collected from the estuarine waters of Davis Bayou and bloomed in outdoor tanks from which it was harvested and fed to red sapper larvae. -

A Comparison of Copepoda (Order: Calanoida, Cyclopoida, Poecilostomatoida) Density in the Florida Current Off Fort Lauderdale, Florida

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks HCNSO Student Theses and Dissertations HCNSO Student Work 6-1-2010 A Comparison of Copepoda (Order: Calanoida, Cyclopoida, Poecilostomatoida) Density in the Florida Current Off orF t Lauderdale, Florida Jessica L. Bostock Nova Southeastern University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occ_stuetd Part of the Marine Biology Commons, and the Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons Share Feedback About This Item NSUWorks Citation Jessica L. Bostock. 2010. A Comparison of Copepoda (Order: Calanoida, Cyclopoida, Poecilostomatoida) Density in the Florida Current Off Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Master's thesis. Nova Southeastern University. Retrieved from NSUWorks, Oceanographic Center. (92) https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occ_stuetd/92. This Thesis is brought to you by the HCNSO Student Work at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in HCNSO Student Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nova Southeastern University Oceanographic Center A Comparison of Copepoda (Order: Calanoida, Cyclopoida, Poecilostomatoida) Density in the Florida Current off Fort Lauderdale, Florida By Jessica L. Bostock Submitted to the Faculty of Nova Southeastern University Oceanographic Center in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science with a specialty in: Marine Biology Nova Southeastern University June 2010 1 Thesis of Jessica L. Bostock Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Science: Marine Biology Nova Southeastern University Oceanographic Center June 2010 Approved: Thesis Committee Major Professor :______________________________ Amy C. Hirons, Ph.D. Committee Member :___________________________ Alexander Soloviev, Ph.D. -

A New Species of Monstrillopsis (Crustacea, Copepoda, Monstrilloida) from the Lower Northwest Passage of the Canadian Arctic

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 709: 1–16 A(2017) new species of Monstrillopsis (Crustacea, Copepoda, Monstrilloida)... 1 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.708.20181 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research A new species of Monstrillopsis (Crustacea, Copepoda, Monstrilloida) from the lower Northwest Passage of the Canadian Arctic Aurélie Delaforge1, Eduardo Suárez-Morales2, Wojciech Walkusz3, Karley Campbell1, C. J. Mundy1 1 Centre for Earth Observation Science (CEOS), Faculty of Environment, Earth and Resources, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3T 2N2 2 El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR), Unidad Chetumal. P.O. Box 424. Chetumal, Quintana Roo 77014. Mexico 3 Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3T 2N6 Corresponding author: Eduardo Suárez-Morales ([email protected]) Academic editor: D. Defaye | Received 21 August 2017 | Accepted 4 October 2017 | Published 18 October 2017 http://zoobank.org/FC4FADA8-EDDD-41CF-AB6B-2FE812BC8452 Citation: Delaforge A, Suárez-Morales E, Walkusz W, Campbell K, Mundy CJ (2017) A new species of Monstrillopsis (Crustacea, Copepoda, Monstrilloida) from the lower Northwest Passage of the Canadian Arctic. ZooKeys 709: 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.709.20181 Abstract A new species of monstrilloid copepod, Monstrillopsis planifrons sp. n., is described from an adult female that was collected beneath snow-covered sea ice during the 2014 Ice Covered Ecosystem – CAMbridge bay Process Study (ICE-CAMPS) in Dease Strait -

Grazing by the Calanoid Copepod Neocalanus Cristatus on the Microbial Food Web in the Coastal Gulf of Alaska

JOURNAL OF PLANKTON RESEARCH j VOLUME 27 j NUMBER 7 j PAGES 647–662 j 2005 Grazing by the calanoid copepod Neocalanus cristatus on the microbial food web in the coastal Gulf of Alaska HONGBIN LIU1, MICHAEL J. DAGG1* AND SUZANNE STROM2 1 2 LOUISIANA UNIVERSITIES MARINE CONSORTIUM, 8124 HIGHWAY 56, CHAUVIN, LA 70344, USA AND SHANNON POINT MARINE CENTER, WESTERN WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY, 1900 SHANNON POINT ROAD, ANACORTES, WA 98221, USA *CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: [email protected] Received March 13, 2005; accepted in principle May 11, 2005; accepted for publication June 10, 2005; published online June 22, 2005 Communicating editor: K.J. Flynn Neocalanus cristatus feeding on phytoplankton and microzooplankton was measured in the coastal Gulf of Alaska during spring and early summer of 2001 and 2003. Neocalanus cristatus CV fed primarily on particles >20 m. Particles in the 5- to 20-m size range were ingested in some experiments under nonbloom conditions but not under bloom conditions. Particles <5 m were not ingested but increased during incubations because N. cristatus consumed their microzooplanktonic predators. Neocalanus cristatus are sufficiently abundant in nature to induce such a cascade effect in situ. Microzooplankton provided >70% of the carbon ingested by N. cristatus under nonbloom conditions but only 30% under bloom conditions. Neocalanus cristatus ingested about two times more carbon under bloom conditions (average 21.4 g C copepod–1 day–1) than under nonbloom conditions (average 10.0 g C copepod–1 day–1), but these rates were inadequate to meet nutritional demands for growth and metabolism, estimated to be between 40 and 140 gC copepod–1 day–1.