Evaporation of Water with Emphasis on Applications and Measurements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

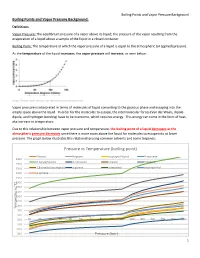

Pressure Vs Temperature (Boiling Point)

Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background: Definitions Vapor Pressure: The equilibrium pressure of a vapor above its liquid; the pressure of the vapor resulting from the evaporation of a liquid above a sample of the liquid in a closed container. Boiling Point: The temperature at which the vapor pressure of a liquid is equal to the atmospheric (or applied) pressure. As the temperature of the liquid increases, the vapor pressure will increase, as seen below: https://www.chem.purdue.edu/gchelp/liquids/vpress.html Vapor pressure is interpreted in terms of molecules of liquid converting to the gaseous phase and escaping into the empty space above the liquid. In order for the molecules to escape, the intermolecular forces (Van der Waals, dipole- dipole, and hydrogen bonding) have to be overcome, which requires energy. This energy can come in the form of heat, aka increase in temperature. Due to this relationship between vapor pressure and temperature, the boiling point of a liquid decreases as the atmospheric pressure decreases since there is more room above the liquid for molecules to escape into at lower pressure. The graph below illustrates this relationship using common solvents and some terpenes: Pressure vs Temperature (boiling point) Ethanol Heptane Isopropyl Alcohol B-myrcene 290.0 B-caryophyllene d-Limonene Linalool Pulegone 270.0 250.0 1,8-cineole (eucalyptol) a-pinene a-terpineol terpineol-4-ol 230.0 p-cymene 210.0 190.0 170.0 150.0 130.0 110.0 90.0 Temperature (˚C) Temperature 70.0 50.0 30.0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 200 300 400 500 600 760 10.0 -10.0 -30.0 Pressure (torr) 1 Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background As a very general rule of thumb, the boiling point of many liquids will drop about 0.5˚C for a 10mmHg decrease in pressure when operating in the region of 760 mmHg (atmospheric pressure). -

It's Just a Phase!

BASIS Lesson Plan Lesson Name: It’s Just a Phase! Grade Level Connection(s) NGSS Standards: Grade 2, Physical Science FOSS CA Edition: Grade 3 Physical Science: Matter and Energy Module *Note to teachers: Detailed standards connections can be found at the end of this lesson plan. Teaser/Overview Properties of matter are illustrated through a series of demonstrations and hands-on explorations. Students will learn to identify solids, liquids, and gases. Water will be used to demonstrate the three phases. Students will learn about sublimation through a fun experiment with dry ice (solid CO2). Next, they will compare the propensity of several liquids to evaporate. Finally, they will learn about freezing and melting while making ice cream. Lesson Objectives ● Students will be able to identify the three states of matter (solid, liquid, gas) based on the relative properties of those states. ● Students will understand how to describe the transition from one phase to another (melting, freezing, evaporation, condensation, sublimation) ● Students will learn that matter can change phase when heat/energy is added or removed Vocabulary Words ● Solid: A phase of matter that is characterized by a resistance to change in shape and volume. ● Liquid: A phase of matter that is characterized by a resistance to change in volume; a liquid takes the shape of its container ● Gas: A phase of matter that can change shape and volume ● Phase change: Transformation from one phase of matter to another ● Melting: Transformation from a solid to a liquid ● Freezing: Transformation -

Lecture 11. Surface Evaporation and Soil Moisture (Garratt 5.3) in This

Atm S 547 Boundary Layer Meteorology Bretherton Lecture 11. Surface evaporation and soil moisture (Garratt 5.3) In this lecture… • Partitioning between sensible and latent heat fluxes over moist and vegetated surfaces • Vertical movement of soil moisture • Land surface models Evaporation from moist surfaces The partitioning of the surface turbulent energy flux into sensible vs. latent heat flux is very important to the boundary layer development. Over ocean, SST varies relatively slowly and bulk formulas are useful, but over land, the surface temperature and humidity depend on interactions of the BL and the surface. How, then, can the partitioning be predicted? For saturated ideal surfaces (such as saturated soil or wet vegetation), this is relatively straight- forward. Suppose that the surface temperature is T0. Then the surface mixing ratio is its saturation value q*(T0). Let z1 denote a measurement height within the surface layer (e. g. 2 m or 10 m), at which the temperature and humidity are T1 and q1. The stability is characterized by an Obhukov length L. The roughness length and thermal roughness lengths are z0 and zT. Then Monin-Obuhkov theory implies that the sensible and latent heat fluxes are HS = ρLvCHV1 (T0 - T1), HL = ρLvCHV1 (q0 - q1), where CH = fn(V1, z1, z0, zT, L)" We can eliminate T0 using a linearized version of the Clausius-Clapeyron equations: q0 - q*(T1) = (dq*/dT)R(T0 - T1), (R indicates a reference temp. near (T0 + T1)/2) HL = s*HS +!LCHV1(q*(T1) - q1), (11.1) s* = (L/cp)(dq*/dT)R (= 0.7 at 273 K, 3.3 at 300 K) This equation expresses latent heat flux in terms of sensible heat flux and the saturation deficit at the measurement level. -

Recap: First Law of Thermodynamics Joule: 4.19 J of Work Raised 1 Gram Water by 1 ºC

Recap: First Law of Thermodynamics Joule: 4.19 J of work raised 1 gram water by 1 ºC. This implies 4.19 J of work is equivalent to 1 calorie of heat. • If energy is added to a system either as work or as heat, the internal energy is equal to the net amount of heat and work transferred. • This could be manifest as an increase in temperature or as a “change of state” of the body. • First Law definition: The increase in internal energy of a system is equal to the amount of heat added minus the work done by the system. ΔU = increase in internal energy ΔU = Q - W Q = heat W = work done by system Note: Work done on a system increases ΔU. Work done by system decreases ΔU. Change of State & Energy Transfer First law of thermodynamics shows how the internal energy of a system can be raised by adding heat or by doing work on the system. U -W ΔU = Q – W Q Internal Energy (U) is sum of kinetic and potential energies of atoms /molecules comprising system and a change in U can result in a: - change on temperature - change in state (or phase). • A change in state results in a physical change in structure. Melting or Freezing: • Melting occurs when a solid is transformed into a liquid by the addition of thermal energy. • Common wisdom in 1700’s was that addition of heat would cause temperature rise accompanied by melting. • Joseph Black (18th century) established experimentally that: “When a solid is warmed to its melting point, the addition of heat results in the gradual and complete liquefaction at that fixed temperature.” • i.e. -

Lecture 8 Phases, Evaporation & Latent Heat

LECTURE 8 PHASES, EVAPORATION & LATENT HEAT Lecture Instructor: Kazumi Tolich Lecture 8 2 ¨ Reading chapter 17.4 to 17.5 ¤ Phase equilibrium ¤ Evaporation ¤ Latent heats n Latent heat of fusion n Latent heat of vaporization n Latent heat of sublimation Phase equilibrium & vapor-pressure curve 3 ¨ If a substance has two or more phases that coexist in a steady and stable fashion, the substance is in phase equilibrium. ¨ The pressure of the gas when equilibrium is reached is called equilibrium vapor pressure. ¨ A plot of the equilibrium vapor pressure versus temperature is called vapor-pressure curve. ¨ A liquid boils at the temperature at which its vapor pressure equals the external pressure. Phase diagram 4 ¨ A fusion curve indicates where the solid and liquid phases are in equilibrium. ¨ A sublimation curve indicates where the solid and gas phases are in equilibrium. ¨ A plot showing a vapor-pressure curve, a fusion curve, and a sublimation curve is called a phase diagram. ¨ The vapor-pressure curve comes to an end at the critical point. Beyond the critical point, there is no distinction between liquid and gas. ¨ At triple point, all three phases, solid, liquid, and gas, are in equilibrium. ¤ In water, the triple point occur at T = 273.16 K and P = 611.2 Pa. Quiz: 1 5 ¨ In most substance, as the pressure increases, the melting temperature of the substance also increases because a solid is denser than the corresponding liquid. But in water, ice is less dense than liquid water. Does the fusion curve of water have a positive or negative slope? A. -

Phase Changes Do Now

Phase Changes Do Now: What are the names for the phases that matter goes through when changing from solid to liquid to gas, and then back again? States of Matter - Review By adding energy, usually in the form of heat, the bonds that hold a solid together can slowly break apart. The object goes from one state, or phase, to another. These changes are called PHASE CHANGES. Solids A solid is an ordered arrangement of particles that have very little movement. The particles vibrate back and forth but remain closely attracted to each other. Liquids A liquid is an arrangement of less ordered particles that have gained energy and can move about more freely. Their attraction is less than a solid. Compare the two states: Gases By adding energy, solids can change from an ordered arrangement to a less ordered arrangement (liquid), and finally to a very random arrangement of the particles (the gas phase). Each phase change has a specific name, based on what is happening to the particles of matter. Melting and Freezing The solid, ordered The less ordered liquid molecules gain energy, molecules loose energy, collide more, and slow down, and become become less ordered. more ordered. Condensation and Vaporization The more ordered liquid molecules gain energy, speed The less ordered gas up, and become less ordered. molecules loose energy, Evaporation only occurs at slow down, and become the surface of a liquid. more ordered. Boiling occurs throughout the liquid. The linked image cannot be displayed. The file may have been moved, renamed, or deleted. Verify that the link points to the correct file and location. -

The Particle Model of Matter 5.1

The Particle Model of Matter 5.1 More than 2000 years ago in Greece, a philosopher named Democritus suggested that matter is made up of tiny particles too small to be seen. He thought that if you kept cutting a substance into smaller and smaller pieces, you would eventually come to the smallest possible particles—the building blocks of matter. Many years later, scientists came back to Democritus’ idea and added to it. The theory they developed is called the particle model of matter. LEARNING TIP There are four main ideas in the particle model: Are you able to explain the 1. All matter is made up of tiny particles. particle model of matter in your own words? If not, re-read the main ideas and examine the illustration that goes with each. 2. The particles of matter are always moving. 3. The particles have spaces between them. 4. Adding heat to matter makes the particles move faster. heat Scientists find the particle model useful for two reasons. First, it provides a reasonable explanation for the behaviour of matter. Second, it presents a very important idea—the particles of matter are always moving. Matter that seems perfectly motionless is not motionless at all. The air you breathe, your books, your desk, and even your body all consist of particles that are in constant motion. Thus, the particle model can be used to explain the properties of solids, liquids, and gases. It can also be used to explain what happens in changes of state (Figure 1 on the next page). NEL 5.1 The Particle Model of Matter 117 The particles in a solid are held together strongly. -

3.3 Definitions & Notes PHASE CHANGES

3.3 Definitions & Notes PHASE CHANGES WORDS FOR DEFINITIONS YOU NEED ARE IN RED Phase Heat of Heat of Endothermic exothermic change fusion vaporization vaporization Evaporation Vapor condensation sublimation pressure deposition PHASE CHANGE: thermal energy (HEAT) is transferred to or from a substance that causes a change in phase. During a phase change the temperature of the substance does not change A phase change is reversible ( can be undone or the substance can be returned to its original state) Phase change is a physical change, NOT A CHEMICAL CHANGE. Why doesn’t temperature change during a phase change? The thermal energy is consumed while breaking bonds. EXAMPLES: Ice absorbs heat to melt to liquid water. Liquid water gives off heat and freezes. TRANSITION: when a substance is moving from one phase to another it is in TRANSITION As a verb “ A substance is transitioning” – changing. EXO THERMIC: when heat is given off (Ex means – outside) ENDO THERMRIC: when heat is taken in THE TRANSITIONS WE ALREADY KNOW TRANSITION Description The transition from solid to liquid Melting Heat is absorbed by substance or added to substance The transition from liquid to solid Freezing Heat is given off by substance or absorbed by the surroundings The transition from Gas to liquid Condensation Heat is given off by substance or absorbed by the surroundings The transition from Liquid to Gas AT the Boiling point Vaporization Heat is absorbed by substance or added to substance The transition from Liquid to Gas BELOW the Boiling Evaporation point Heat is absorbed by substance or added to substance THE TRANSITIONS WE MAY NOT ALREADY KNOW TRANSITION Description The transition from solid directly to gas SUBLIMATION Heat is absorbed by substance or added to substance Example? The transition from gas directly to solid DEPOSITION Heat is given off by the substance or taken away Example? Data from Melting/Freezing Lab done with Napthalene TEMPERATURE CHANGING Do I need to write this down? Write down what you need. -

Estimating Evaporation from Water Surfaces

ESTIMATING EVAPORATION FROM WATER SURFACES1 By Marvin E. Jensen2 INTRODUCTION Because of its nature, evaporation from water surfaces is rarely measured directly, except over relatively small spatial and temporal scales (Jones 1992). Evaporation from water is most commonly computed indirectly by one or more techniques. These include pan coefficients × measured pan evaporation, water balance, energy balance, mass transfer, and combination techniques. The selection of the "best" technique to use for a particular computation is largely a function of the data availability, type or size of the water body, and the required accuracy of the estimated evaporation. The most commonly used method in the US for estimating evaporation from small, shallow water bodies, is to measure evaporation from a standard pan and then multiply by a coefficient. The purpose of this brief paper is to describe some principles involved in estimating evaporation with example data from large and small water bodies. Particular emphasis will be on practical procedures and techniques that professionals can use to estimate evaporation from shallow water bodies using pan evaporation and a combination equation using available weather data and/or new data collected specifically for estimating daily evaporation. BACKGROUND Theories of evaporation from water surfaces go back to at least the 8th century B.C., but measurement and experimentation go back to the 17th and 18th centuries. Brutsaert (1982) credits Dalton’s 1802 paper (cited by Brutsaert 1982, p. 31) as a major event in the development of evaporation theory. He expressed Dalton’s results in present day notation as E =f(ū)(eo – ea) where E is the rate of evaporation expressed as rate per unit time, ū is mean wind speed, eo is the saturation vapor pressure at the temperature of the water surface and ea is the vapor pressure of the air. -

Evaporation from Water Bodies Clearly, in Nature, Evaporation From

Evaporation from Water Bodies Clearly, in nature, evaporation from a water body like an ocean or a lake must depend on a number of factors. In the conceptual experiment we ran in class, we kept the temperature of the liquid constant and then watched how evaporation created an “atmosphere” of water vapor at roughly the same temperature. In nature, air masses can be warmer or colder than the underlying ocean. Also, the temperature of the ocean or lake will govern how much water vapor will “try” to evaporate and the amount of water vapor thus evaporated does not vary linearly with temperature. Finally, the relative humidity of the overlying air (as a measure of how much water vapor is already present in the overlying atmosphere) clearly will be important. If the overlying air is saturated, then the ability for net evaporation to take place from the water body will be limited. One equation that has seen some success in quantifying these things is the so called “Lake Mead Equation”: -1 E = 0.0331 V (e – es) [1 – 0.03 (T – Tw)] 24 h day (1) where E is evaporation rate (mm/day); V is the wind speed in the lowest 0.5 m above the ground (km/h), e is vapor pressure (the equation is setup to use the English system unit mm Hg), es is saturation vapor pressure, T is the atmospheric temperature above the water surface in C, and Tw is the water temperature in C. Equation (1) says that the evaporation rate is directly related to wind speed, and the greater the difference between the vapor pressure and saturation vapor pressure (the lower the relative humidity). -

Evaporation and Condensation Directions: Read, Highlight, and Once You Are Finished Reading, Go to Schoology.Com to Answer Questions

Name: ______________________________ Evaporation and Condensation Directions: Read, highlight, and once you are finished reading, go to schoology.com to answer questions. Evaporation Evaporation is the scientific name for liquid turning into a gas. The temperature where liquid turns into a gas is called the boiling point. Every substance on earth has a different boiling point. This should sound very similar to what you read for melting points. Water has a boiling point of 100oC (212oF), a temperature special to water only. As a liquid approaches its boiling point, the particles absorb more heat energy making them vibrate faster. When liquids reach their boiling point, the particles don’t continue to vibrate faster. You saw this when we boiled water (and when we melted ice). The heat goes into break the attraction the particles have to each other. When liquid particles gain enough energy to overcome the attraction holding them together, they become a gas. Once liquids become a gas, the molecules can move faster. Instead of sliding over each other like a liquid, they can fly around attracted to nothing. Molecules that are evaporating are absorbing heat. Because the molecules are absorbing heat, evaporation is called endothermic. Remember, endo means “to enter” while thermic means “heat.” Condensation The opposite of evaporation is condensation. Condensation happens when a gas changes back to a liquid. We see condensation happen every time clouds turn into rain. Clouds are a gas. Rain is a liquid. When the clouds turn into rain, condensation happens. Condensation happens because the gas loses heat energy. For water, condensation happens at 100oC (212oF). -

Deriving Properties of Low-Volatile Substances from Isothermal Evaporation Curves

J. Non-Equilib. Thermodyn. 2016; 41 (1):3–11 Research Article Ricardas V. Ralys*, Alexander A. Uspenskiy and Alexander A. Slobodov Deriving properties of low-volatile substances from isothermal evaporation curves DOI: 10.1515/jnet-2015-0030 Received May 31, 2015; revised October 8, 2015; accepted October 19, 2015 Abstract: Mass ux occurring when a substance evaporates from an open surface is proportional to its satu- rated vapor pressure at a given temperature. The proportionality coecient that relates this ux to the vapor pressure shows how far a system is from equilibrium and is called the accommodation coecient. Under vac- uum, when a system deviates from equilibrium to the greatest extent possible, the accommodation coecient equals unity. Under nite pressure, however, the accommodation coecient is no longer equal to unity, and in fact, it is much less than unity. In this article, we consider the isothermal evaporation or sublimation of low- volatile individual substances under conditions of thermogravimetric analysis, when the external pressure of the purging gas is equal to the atmospheric pressure and the purging gas rate varies. When properly treated, the dependence of sample mass over time provides us with various information on the properties of the exam- ined compound, such as saturated vapor pressure, diusion coecient, and density of the condensed (liquid or solid) phase at the temperature of experiment. We propose here the model describing the accommodation coecient as a function of both substance properties and experimental conditions. This model gives the - nal expression for evaporation rate, and thus for mass dependence over time, with approximation parameters resulting in the properties being sought.