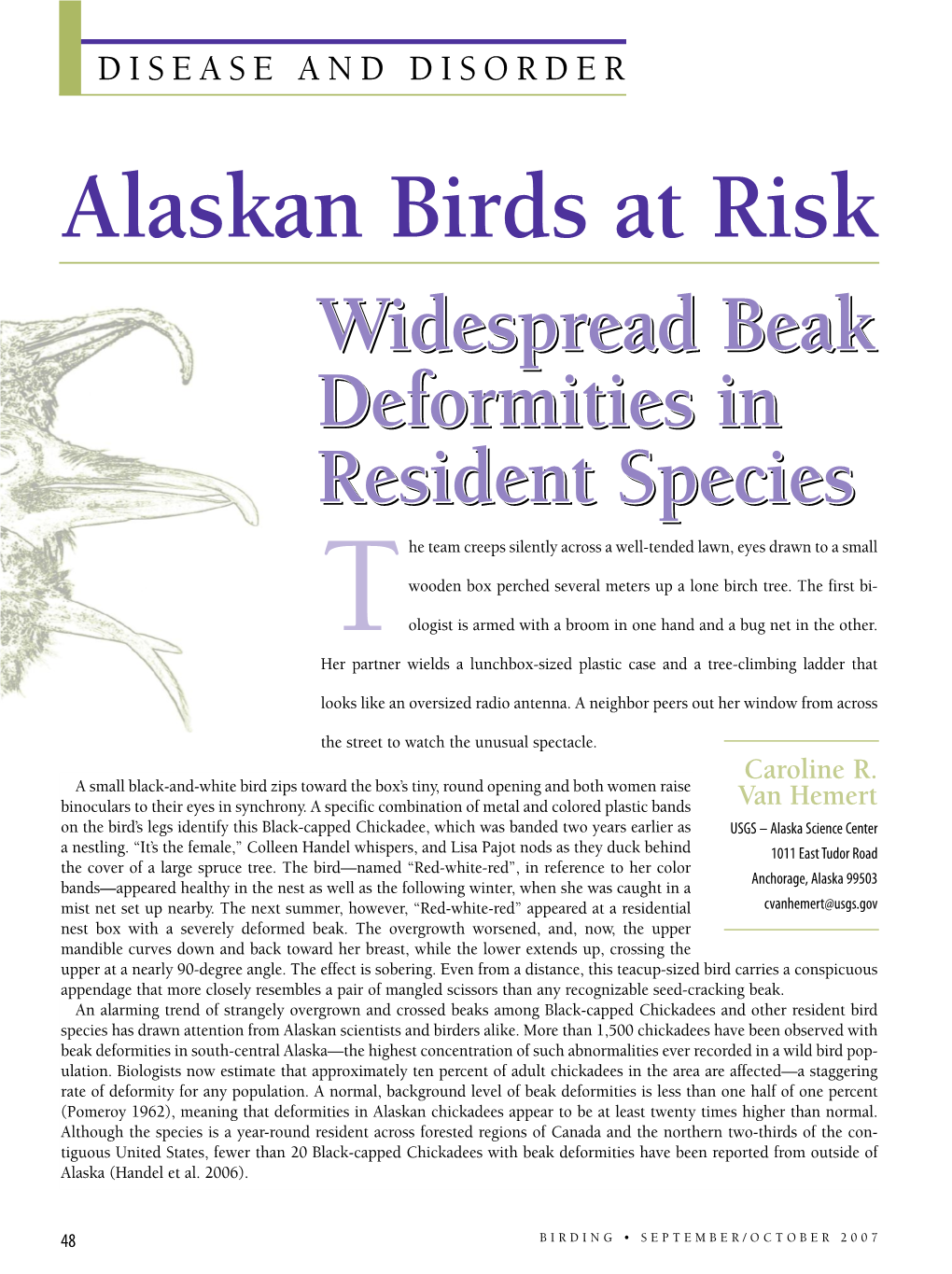

Alaskan Birds at Risk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Global Assessment of the Conservation Status of the Black Oystercatcher Haematopus Bachmani

A global assessment of the conservation status of the Black Oystercatcher Haematopus bachmani David F. Tessle r1, James A. Johnso n2, Brad A. Andres 3, Sue Thoma s4 & Richard B. Lancto t2 1Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Wildlife Conservation, Wildlife Diversity Program, 333 Raspberry Road, Anchorage, Alaska 99518 USA. [email protected] 2United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Migratory Bird Management, 1011 East Tudor Road, MS 201, Anchorage, Alaska 99503 USA 3United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Migratory Bird Management, 755 Parfet Street, Suite 235, Lakewood, Colorado 80215 USA 4United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington Maritime National Wildlife Refuge Complex, 715 Holgerson Road, Sequim, Washington 98382 USA Tessler, D.F., J.A. Johnson, B.A. Andres, S. Thomas, & R.B. Lanctot. 2014. A global assessment of the conser - vation status of the Black Oystercatcher Haematopus bachmani . International Wader Studies 20: 83 –96. The Black Oystercatcher Haematopus bachmani , a monotypic species, is one of the less studied members of the genus. The global population of roughly 10,000 individuals is scattered unevenly along the North American Pacific Ocean coast from the Aleutian Islands to Baja California, with the vast majority (about 80%) in Alaska and British Columbia. Favouring rocky shorelines in areas of high tidal variation, they forage exclusively on intertidal macroinvertebrates (e.g. limpets and mussels). Because they are completely dependent on marine shorelines, the Black Oystercatcher is considered a sensitive indicator of the health of the rocky intertidal community. Breeding oystercatchers are highly territorial, and nesting densities are generally low; however, during the winter months they tend to aggregate in groups of tens to hundreds. -

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

Cryptic and Extensive Hybridization Between Ancient Lineages of American Crows

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/491654; this version posted December 10, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Cryptic and extensive hybridization between ancient lineages of American crows David L. Slager1,2*, Kevin L. Epperly1,2, Renee R. Ha3, Sievert Rohwer1,2, Chris Wood2, Caroline Van Hemert4, and John Klicka1,2 1Department of Biology, University of Washington, Box 351800, Seattle, WA 98115, USA 2Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, Box 353010, Seattle, WA 98195, USA 3Department of Psychology, University of Washington, Box 351525, Seattle, WA 98195, USA 4US Geological Survey, Alaska Science Center, 4210 University Drive, Anchorage, AK 99508, USA *Corresponding author; email: [email protected]; website: https://slager.github.io Abstract Most species and therefore most hybrid zones have historically been described using phenotypic characters. However, both speciation and hybridization can occur with neg- ligible morphological differentiation. The Northwestern Crow (Corvus caurinus) and American Crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos) are sister taxonomic species with a continu- ous distribution that lack reliable traditional characters for identification. In this first population genomic study of Northwestern and American crows, we use genomic SNPs (nuDNA) and mtDNA to investigate whether these crows are genetically differentiated and the extent to which they may hybridize. We found that American and North- western crows have distinct evolutionary histories, supported by two nuDNA ancestry clusters and two 1.1%-divergent mtDNA clades dating to the late Pleistocene, when glacial advances may have isolated crow populations in separate refugia. -

Pellet-Casting by a Western Scrub-Jay Mary J

NOTES PELLET-CASTING BY A WESTERN SCRUB-JAY MARY J. ELPERS, Starr Ranch Bird Observatory, 100 Bell Canyon Rd., Trabuco Canyon, California 92679 (current address: 3920 Kentwood Ct., Reno, Nevada 89503); [email protected] JEFF B. KNIGHT, State of Nevada Department of Agriculture, Insect Survey and Identification, 350 Capitol Hill Ave., Reno, Nevada 89502 Pellet casting in birds of prey, particularly owls, is widely known. It is less well known that a wide array of avian species casts pellets, especially when their diets contain large amounts of arthropod exoskeletons or vertebrate bones. Currently pellet casting has been documented for some 330 species in more than 60 families (Tucker 1944, Glue 1985). Among the passerines reported to cast pellets are eight species of corvids: the Blue Jay (Cyanocitta cristata) (Lamore 1958, Tarvin and Woolfenden 1999), Pinyon Jay (Gymnorhinus cyanocephalus) (Balda 2002), Gray Jay (Perisoreus canadensis) (Strickland and Ouellet 1993), Black-billed Magpie (Pica hudsonia) (Trost 1999), Yellow-billed Magpie (Pica nuttalli) (Reynolds 1995), American Crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos) (Verbeek and Caffrey 2002), Northwestern Crow (Corvus caurinus) (Butler 1974), and Common Raven (Corvus corax) (Temple 1974, Harlow et al. 1975, Stiehl and Trautwein 1991, Boarman and Heinrich 1999). However, the behavior has not been recorded in the four species of Aphelocoma jays (Curry et al. 2002, Woolfenden and Fitzpatrick 1996, Curry and Delaney 2002, Brown 1994). Here we report an observation of regurgitation of a pellet by a Western Scrub-Jay (Aphelocoma californica) and describe the specimen and its contents. The Western Scrub-Jay is omnivorous and forages on a variety of arthropods as well as plant seeds and small vertebrates (Curry et al. -

Detectability and Occupancy of the Common Raven in Cliff Habitat of Central Appalachia and Southeastern Kentucky

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Forestry and Natural Resources Forestry and Natural Resources 2018 DETECTABILITY AND OCCUPANCY OF THE COMMON RAVEN IN CLIFF HABITAT OF CENTRAL APPALACHIA AND SOUTHEASTERN KENTUCKY Joshua Michael Felch University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2018.068 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Felch, Joshua Michael, "DETECTABILITY AND OCCUPANCY OF THE COMMON RAVEN IN CLIFF HABITAT OF CENTRAL APPALACHIA AND SOUTHEASTERN KENTUCKY" (2018). Theses and Dissertations-- Forestry and Natural Resources. 39. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/forestry_etds/39 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Forestry and Natural Resources at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Forestry and Natural Resources by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Avian Prey-Dropping Behavior. II. American Crows and Walnuts

Behavioral Ecology Vol. 10 No. 3: 220±226 Avian prey-dropping behavior. II. American crows and walnuts Daniel A. Cristola and Paul V. Switzerb aDepartment of Biology, The College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA 23187-8795, USA, and bDepartment of Zoology, Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, IL 61920, USA Complex and energetically expensive foraging tasks should be shaped by natural selection to be ef®cient. Many species of birds open hard-shelled prey by dropping the prey repeatedly onto the ground from considerable heights. Urban-dwelling American crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos) forage in this way on two species of walnuts in central California, USA. As predicted from a theoretical model, crows dropped nuts with harder shells from greater heights and dropped them from greater heights when over softer substrates. The height selected for dropping nuts decreased in the presence of numerous nearby conspeci®cs, indicating that crows were sensitive to the risk of kleptoparasitism when selecting drop heights. Drop height decreased with repeated drops of the same walnut, suggesting that crows adjusted for the increasing likelihood that a repeatedly-dropped nut would break on subsequent drops. Crows did not alter height of drop in accordance with differences in the mass of the prey. When faced with multiple prey types and dropping substrates, and high rates of attempted kleptoparasitism, crows adjusted the height from which they dropped nuts in ways that decreased the likelihood of kleptoparasitism and increased the energy obtained from each nut. Key words: American crow, Corvus brachyrhynchos, foraging behavior, Juglans spp., kleptoparasitism, prey dropping, walnuts. [Behav Ecol 10:220±226 (1999)] irds that break open hard-shelled prey items by dropping dictions of our model on a previously undescribed avian prey- B them repeatedly onto the ground have attracted scien- dropping system. -

Corvid Response to Human Settlements and Campgrounds: Causes, Consequences, and Challenges for Conservation

BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION 130 (2006) 301– 314 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Corvid response to human settlements and campgrounds: Causes, consequences, and challenges for conservation John M. Marzluff*, Erik Neatherlin Ecosystem Sciences Division, College of Forest Resources, University of Washington, Box 352100, Seattle, WA 98195-2100, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Human development often favors species adapted to human conditions with subsequent Received 14 August 2004 negative effects on sensitive species. This is occurring throughout the urbanizing world Received in revised form as increases by generalist omnivores, like some crows and ravens (corvids) threaten other 5 December 2005 birds with increased rates of nest predation. The process of corvid responses and their Accepted 20 December 2005 actual effects on other species is only vaguely understood, so we quantified the population Available online 9 February 2006 response of radio-tagged American crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos), common ravens (Corvus corax), and Steller’s jays (Cyanocitta stelleri) to human settlements and campgrounds and Keywords: examined their influence as nest predators on simulated marbled murrelet (Brachyramphus Anthropogenic disturbance marmoratus) nests on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula from 1995 to 2000. The behavior and American crow demography of crows, ravens, and jays was correlated to varying degrees with proximity to Camping human development. Crows and ravens had smaller home ranges and higher reproduction Common raven near human settlements and recreation. Annual survival of crows was positively associ- Endangered species ated with proximity to human development. Home range and reproduction of Steller’s jays Home range was independent of proximity to human settlements and campgrounds. -

Klickitat Appendices

Klickitat Appendices Appendix A Developed by the Subbasin Planning Team and Technical Writers Developed from Meeting Minutes, Meeting Attendees Lists and other sources Developed on 5/21/04 Klickitat Subbasin Planners and Contributors Fisheries Subbasin Coordinator Jeff Spencer, fisheries biologist, Yakama Nation Fisheries Program, Natural Resource Annex, 4690 SR 22, Toppenish, WA 98948; (509) 865-6262; [email protected] Wildlife Subbasin Coordinator Heather Simmons-Rigdon, wildlife biologist, Yakama Nation Wildlife Program, P.O. Box 151, Toppenish, WA 98948; (509) 865-6262; [email protected] Fisheries Subbasin Major Contributors (Writing) Bill Sharp, fisheries biologist, Yakama Nation Fisheries Program, Natural Resource Annex, 4690 SR 22, Toppenish, WA 98948; (509) 865-6262; [email protected] Wildlife Subbasin Major Contributors (Writing) Frederick C. Dobler, Southwest Region wildlife manager, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, 2108 Grand Blvd., Vancouver, WA 98661; (360) 906-6722. Jeff Kozma, TFW wildlife biologist, Yakama Nation, P.O. Box 151, Toppenish, WA 98948: (509) 865-6262; [email protected] David P. Anderson, district wildlife biologist, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, P.O. Box 68, Trout Lake, WA, 98650; 509-395-2232 (w); [email protected] Tracy Hames, game bird biologist, Yakama Nation Wildlife Program, P.O. Box 151, Toppenish, WA 98948; (509) 865-6262; [email protected] Scott M. McCorquodale, Ph.D., deer and elk specialist, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Wildlife Management Program, 1701 South 24th Ave., Yakima, WA 98902; (509) 457- 9322; [email protected] Eric Holman, wildlife biologist, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Wildlife Program – Region 5, 2108 Grand Boulevard, Vancouver, WA 98661; [email protected] Paul Ashley, wildlife biologist, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (retired), Wildlife Program – Spokane; [email protected] Stacey H. -

The Breeding Ecology and Social Organization of the Northwestern Crow (Corvus, Caurinus) Was Studied Fron 19 May Ta

:. - * - I, 3,~16:i*?p,e labma, @ CA~AD~ANTHESES TH~SESCANADIENNLS rj :'-@,7 , 6 Cartaaa ON MiCROFICHE SUR MICROFICHE - - .. - --. -:as ~re2lingecology and social organization of the Northwestern --- - .. -.. 7 T. TGE CE :A Cr3~(Covus caurinus) on Miflenatch Island, B. C. T , . -- 'ri5 3 ;I&S K)ESEhTED !4aster of Science - _c? CETTi THESE FUT PR~S€NT€E 1 1980 --- ..p. - rt LL T-c~~~E~):ANN/ED'OBTEhiTlCbV DE CE GRADE 5 - ;- $5 -ermy srated to the NATtCYJAL LIWRY OF L'autorisation est, par la prCsente, accordbe B la BIBLIOTH~ 3-.. .-. icr r :rof,lm this thesis and to lerd or 41copies QUE NATIONALE DU CANADA de rnicrofllmer cette prrkse e -<. 'L - de pdtcr ou de vendre des exernplatres du f~h. 1, : + s r r.s otner pub1 icat~onr~ghts, and neitkr the .L'eutew se rCserve les sutres droits de publ~cnr~on111 1 . NOTICE The quality of this microfiche is heavily dependent La qualite de cette microfiche depend grandement de upon the quality of the original thesis, submitted for la qualite de la these soumise au microfilmage. Nous microfilming. Every effort has been made to ensure avons tout fait pour assurer une qualite superieure rhe highest quality df reproduction pogible. de reproduction, If pages are missing, contact the university which S'il manque des pages, veuillez communiquer granted the degrea avec I'universi'te qui a confere le grade. Some pages may have indistinct print especially La qualite d'impression de certaines pages peut if the original pages were typed with a poor typewriter laisser a desirer, surtout si les pages originates ont ete rib66n or if the university sent us a poor photocopy. -

Acoustic Evidence of Relationship in North American Crows

ACOUSTIC EVIDENCE OF RELATIONSHIP IN NORTH AMERICAN CROWS BY L. IRBY DAVIS k HERE has been much difference of opinion as to how the crows of North I ’ America should be classified. The Northwestern Crow (Corvus caurinus) was originally described as a distinct species, but later (1931) listed as a race of the Common Crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos) by the American Ornithol- ogists ’ Union Committee. After retaining that classification for many years, the latest “Checklist” (1957) a g ain elevates the Northwestern Crow to full specific rank. (In the meantime it had been listed as a race of the Fish Crow, C. ossifragus, by Hellmayr, 1934.) In a similar manner there has been con- siderable discussion as to whether or not isolated populations, such as the ’ ’ Fish Crow of the eastern United States and the Mexican crows should be considered conspecific. (C. imparatus was listed as a race of C. ossifragus by Blake in 1953). When one reads the published data on various forms in museum collections, it becomes apparent why there is so much difficulty in trying to set up a classification based upon such morphological findings as are revealed by the skins. Using the data published by Ridgway (1904:266- 275), one will find that (with the exception of the tarsus) the measurements given for the Common Crow overlap completely those of the other two species with which it comes in contact. The longest tarsus reported for a male Fish Crow is 47 mm., and the longest for a male Northwestern Crow is 53 mm., whereas the shortest tarsus given for a male of the western race of the Common Crow (C. -

Western Washington State Custom Trip Report

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA: WESTERN WASHINGTON STATE CUSTOM TRIP REPORT 8 – 15 AUGUST 2019 By Christian Hagenlocher Band-tailed Pigeon was one of the many species we found on this trip. www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | TRIP REPORT Western Washington State August 2019 Overview This custom trip combined some of the classic destinations in western Washington, covering a variety of habitats from pelagic birding to the alpine slopes of Mount Rainier. We drove over 1,000 miles of roads, ranging from highways to logging roads, in search of a wide variety of species. Our total list contained 147 species (and one additional species heard only). The itinerary was adapted from our sister company Bird Treks’ Washington Tour. With only one client signed up we tailored the itinerary to meet her needs and requests for target birds. This itinerary centered around a pelagic day trip with Westport Seabirds, followed by visiting some key birding locations for owls and grouse in addition to secondary western target birds which would be lifers for the client. Detailed Report Day 1, August 8th 2029. Seattle to Westport via Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge We began with a mid-morning pickup from the client’s hotel near SeaTac, from where we jumped into Thursday morning traffic, heading toward downtown Seattle. We chose to begin the trip with a ferry boat ride from Seattle to Bremerton. After boarding the boat we walked to the observation deck with our binoculars and had great looks at the classic “Olympic Gull”— a Western Gull x Glaucous-winged Gull hybrid complex that inhabits Puget Sound. -

American Crow Corvus Brachyrhynchos No Change Among San Diego Birds Has Been More Striking Than the Proliferation of the American Crow

Crows and Jays — Family Corvidae 381 American Crow Corvus brachyrhynchos No change among San Diego birds has been more striking than the proliferation of the American Crow. Until the mid 1980s the species ranged no farther south along the coast than Carlsbad, no nearer the coast in metropolitan San Diego than El Cajon. Then it surged south and west, spreading over the coastal lowland. By the new millennium it was abundant in many areas where it was absent only 15 years earlier. Primitively the crow occurred in oak and riparian woodland near grassland; now orchards, eucalyptus groves, and cities support large numbers. Photo by Anthony Mercieca Breeding distribution: The American Crow now occurs almost throughout the coastal slope of San Diego County, 26 June 1999, R. and S. L. Breisch). The eastern margin most abundantly in the inland valleys of the county’s of the range follows that of oak woodland closely, except northern half. Concentrations during the breeding season that the species occurs uncommonly in San Felipe Valley are as large as 200 at Lake Hodges (K10) 9 March 1999 (R. down to Scissors Crossing (J22; up to nine on 3 June L. Barber), and 220 northeast of Ramona (K15) 26 April 2002, J. R. Barth; fledgling on 13 July 2001, P. Unitt). The 1999 (M. and. B. McIntosh). The crow is abundant locally crow is uncommon and local in montane coniferous for- south to the Mexican border (up to 138 at Potrero, U20, est and absent from sage scrub and chaparral. Its breeding 382 Crows and Jays — Family Corvidae of these in San Diego County is at the east end of Lake Hodges (K11), where counts range up to 1800 on 1 December 1998 (E.