Female-Biased Delayed Dispersal and Helping in American Crows

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Molecular Ecology and Social Evolution of the Eastern Carpenter Bee

Molecular ecology and social evolution of the eastern carpenter bee, Xylocopa virginica Jessica L. Vickruck, B.Sc., M.Sc. Department of Biological Sciences Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Faculty of Mathematics and Science, Brock University St. Catharines, Ontario © 2017 Abstract Bees are extremely valuable models in both ecology and evolutionary biology. Their link to agriculture and sensitivity to climate change make them an excellent group to examine how anthropogenic disturbance can affect how genes flow through populations. In addition, many bees demonstrate behavioural flexibility, making certain species excellent models with which to study the evolution of social groups. This thesis studies the molecular ecology and social evolution of one such bee, the eastern carpenter bee, Xylocopa virginica. As a generalist native pollinator that nests almost exclusively in milled lumber, anthropogenic disturbance and climate change have the power to drastically alter how genes flow through eastern carpenter bee populations. In addition, X. virginica is facultatively social and is an excellent organism to examine how species evolve from solitary to group living. Across their range of eastern North America, X. virginica appears to be structured into three main subpopulations: a northern group, a western group and a core group. Population genetic analyses suggest that the northern and potentially the western group represent recent range expansions. Climate data also suggest that summer and winter temperatures describe a significant amount of the genetic differentiation seen across their range. Taken together, this suggests that climate warming may have allowed eastern carpenter bees to expand their range northward. Despite nesting predominantly in disturbed areas, eastern carpenter bees have adapted to newly available habitat and appear to be thriving. -

Engelsk Register

Danske navne på alverdens FUGLE ENGELSK REGISTER 1 Bearbejdning af paginering og sortering af registret er foretaget ved hjælp af Microsoft Excel, hvor det har været nødvendigt at indlede sidehenvisningerne med et bogstav og eventuelt 0 for siderne 1 til 99. Tallet efter bindestregen giver artens rækkefølge på siden. -

Acacia, Cattle and Migratory Birds in Southeastern Mexico

Biological Conservation 80 (1997) 235-247 © 1997 Elsevier Science Ltd All rights reserved. Printed in Great Britain PII: S0006-3207(96)00137- 1 0006-3207/97 $17.00 + 0.00 ELSEVIER ACACIA, CATTLE AND MIGRATORY BIRDS IN SOUTHEASTERN MEXICO Russell Greenberg,* Peter Bichier & John Sterling Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center, National Zoological Park, Washington, DC 20008, USA (Accepted 11 July 1996) Abstract of forest-dependent migratory birds (Askins et al., Acacia pennatula groves in mid-elevation valleys of 1990). However, the new tropical landscape is usually a southern Mexico supported both the highest density and mosaic of grassland, savanna, ribbons of riparian vege- diversity of migratory birds compared to other habitats in tation and small patches of woods. The wooded habi- the region. In addition, we found the highest numbers for tats, in particular, can support an abundance of over half of the common migratory species. Despite the migratory birds (Powell et al., 1992; Warkentin et al., high degree of leaf loss during the late winter, acacia 1995). One possible strategy for increasing habitat for groves do not experience greater declines in insectivorous migratory birds is the promotion of silvopastoral sys- migratory bird populations than other local habitats. tems which integrate tree management with cattle pro- Color-marked individuals of canopy species had a strong duction on grazing lands. tendency to remain resident within a single acacia grove During several years of censusing birds on the Car- throughout the winter. Management of native acacias on ibbean slope of Chiapas, we discovered that managed subtropical rangelands for wood products, fodder, and soil patches of Acacia pennatula (Schlecht & Cham.) Benth improvement would probably directly and indirectly bene- support particularly high densities of migratory birds. -

The Brown Jay's Furcular Pouch

160 Vol. 44 THE BROWN JAY’S FURCULAR POUCH By GEORGE MIKSCH SUTTON and PERRY W. GILBERT Travelers along northeastern Mexico’s modern highway are apt to remark upon the scarcity of bird life. Those who motor at reasonable speed from Monterrey to Victoria, and thence to Mante, Valles, and Tamazunchale, are sure to see, and almost sure to hear, however, a crow-sized, dark gray-brown bird, with long&h tail, that in- habits the brush of the low country. This bird is in no way handsome, but its boldness, simple coloration, and obvious predilection for the roadside insure its being noticed and talked about. It belongs to that tribe of mischief makers, the Corvidae. It is the Brown Jay, Psilorhinus morio. Fig. 33. Brown Jay (Psilorhinus morio), about one-fiith iife size. Drawing by George Miksch Sutton. July, 1942 THE BROWN JAY’S FURCULAR POUCH 161 The Brown Jay almost never goes about alone. Family groups of ,five or six are the rule, although sometimes when an owl, lynx, human being, or other enemy species is being mobbed, a party of twenty or more may congregate. Excitement then runs high. Each jay must approach ‘Yhe enemy” as closely as it can, so as personally to confirm the “rumors” it has heard. Each jay must scream. If “the enemy” moves, the outcry momentarily stops short; the jays eye each other as if pondering the next move; and the hubbub of screaming starts afresh. When the senior author first encountered the Brown Jay in the vicinity of Monterrey, Nuevo Leon, in February of 1938, he was greatly struck with what he called the bird’s ‘Lhiccup.” This sound, which usually was heard just at the close of the customary scream, but often quite independently of it, was not unlike the syllable puck or buck. -

Gear for a Big Year

APPENDIX 1 GEAR FOR A BIG YEAR 40-liter REI Vagabond Tour 40 Two passports Travel Pack Wallet Tumi luggage tag Two notebooks Leica 10x42 Ultravid HD-Plus Two Sharpie pens binoculars Oakley sunglasses Leica 65 mm Televid spotting scope with tripod Fossil watch Leica V-Lux camera Asics GEL-Enduro 7 trail running shoes GoPro Hero3 video camera with selfie stick Four Mountain Hardwear Wicked Lite short-sleeved T-shirts 11” MacBook Air laptop Columbia Sportswear rain shell iPhone 6 (and iPhone 4) with an international phone plan Marmot down jacket iPod nano and headphones Two pairs of ExOfficio field pants SureFire Fury LED flashlight Three pairs of ExOfficio Give- with rechargeable batteries N-Go boxer underwear Green laser pointer Two long-sleeved ExOfficio BugsAway insect-repelling Yalumi LED headlamp shirts with sun protection Sea to Summit silk sleeping bag Two pairs of SmartWool socks liner Two pairs of cotton Balega socks Set of adapter plugs for the world Birding Without Borders_F.indd 264 7/14/17 10:49 AM Gear for a Big Year • 265 Wildy Adventure anti-leech Antimalarial pills socks First-aid kit Two bandanas Assorted toiletries (comb, Plain black baseball cap lip balm, eye drops, toenail clippers, tweezers, toothbrush, REI Campware spoon toothpaste, floss, aspirin, Israeli water-purification tablets Imodium, sunscreen) Birding Without Borders_F.indd 265 7/14/17 10:49 AM APPENDIX 2 BIG YEAR SNAPSHOT New Unique per per % % Country Days Total New Unique Day Day New Unique Antarctica / Falklands 8 54 54 30 7 4 100% 56% Argentina 12 435 -

Section IV – Guideline for the Texas Priority Species List

Section IV – Guideline for the Texas Priority Species List Associated Tables The Texas Priority Species List……………..733 Introduction For many years the management and conservation of wildlife species has focused on the individual animal or population of interest. Many times, directing research and conservation plans toward individual species also benefits incidental species; sometimes entire ecosystems. Unfortunately, there are times when highly focused research and conservation of particular species can also harm peripheral species and their habitats. Management that is focused on entire habitats or communities would decrease the possibility of harming those incidental species or their habitats. A holistic management approach would potentially allow species within a community to take care of themselves (Savory 1988); however, the study of particular species of concern is still necessary due to the smaller scale at which individuals are studied. Until we understand all of the parts that make up the whole can we then focus more on the habitat management approach to conservation. Species Conservation In terms of species diversity, Texas is considered the second most diverse state in the Union. Texas has the highest number of bird and reptile taxon and is second in number of plants and mammals in the United States (NatureServe 2002). There have been over 600 species of bird that have been identified within the borders of Texas and 184 known species of mammal, including marine species that inhabit Texas’ coastal waters (Schmidly 2004). It is estimated that approximately 29,000 species of insect in Texas take up residence in every conceivable habitat, including rocky outcroppings, pitcher plant bogs, and on individual species of plants (Riley in publication). -

Co-Operative Breeding by Long-Tailed Tits

Co-operative breeding by Long-tailed Tits v — N. W. Glen and C. M. Perrins or most of this century, ornithologists have tended to believe that the Fmajority of birds breed monogamously, with either the pair or, in some species, the female alone raising the brood; to find more than a single pair at a nest was considered to be atypical. Nevertheless, a few species were known where this occurred, and one of these was the Long-tailed Tit Aegithalos caudatus; there are many early references to three or more individuals attending the young at a nest (see Lack & Lack 1958 for some of these). During the last 15 years or so, the view that co-operative breeding was rare has been shattered by a great many studies which have shown that it is in fact widespread among birds. The 'error' seems to have arisen because the vast majority of early studies of birds took place in the north temperate region (mainly in Europe and North America), whereas the large majority of the birds that breed co-operatively occur in the tropics and in southern latitudes. The reasons for this geographic variation have been, and still are, extensively debated. An over-simplification, certainly not tenable in all cases, runs as follows. Some bird species that breed in geographical areas where the climate is relatively equable throughout the year may occupy all the habitat available to them; there are no times of year—as there is, for example, in Britain—when life is so difficult for the birds that many die and there are vacant territories. -

A Global Assessment of the Conservation Status of the Black Oystercatcher Haematopus Bachmani

A global assessment of the conservation status of the Black Oystercatcher Haematopus bachmani David F. Tessle r1, James A. Johnso n2, Brad A. Andres 3, Sue Thoma s4 & Richard B. Lancto t2 1Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Wildlife Conservation, Wildlife Diversity Program, 333 Raspberry Road, Anchorage, Alaska 99518 USA. [email protected] 2United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Migratory Bird Management, 1011 East Tudor Road, MS 201, Anchorage, Alaska 99503 USA 3United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Migratory Bird Management, 755 Parfet Street, Suite 235, Lakewood, Colorado 80215 USA 4United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington Maritime National Wildlife Refuge Complex, 715 Holgerson Road, Sequim, Washington 98382 USA Tessler, D.F., J.A. Johnson, B.A. Andres, S. Thomas, & R.B. Lanctot. 2014. A global assessment of the conser - vation status of the Black Oystercatcher Haematopus bachmani . International Wader Studies 20: 83 –96. The Black Oystercatcher Haematopus bachmani , a monotypic species, is one of the less studied members of the genus. The global population of roughly 10,000 individuals is scattered unevenly along the North American Pacific Ocean coast from the Aleutian Islands to Baja California, with the vast majority (about 80%) in Alaska and British Columbia. Favouring rocky shorelines in areas of high tidal variation, they forage exclusively on intertidal macroinvertebrates (e.g. limpets and mussels). Because they are completely dependent on marine shorelines, the Black Oystercatcher is considered a sensitive indicator of the health of the rocky intertidal community. Breeding oystercatchers are highly territorial, and nesting densities are generally low; however, during the winter months they tend to aggregate in groups of tens to hundreds. -

The Puzzling Vocal Repertoire of the South American Collared Jay, Cyanolyca Iridicyana Merida

THE PUZZLING VOCAL REPERTOIRE OF THE SOUTH AMERICAN COLLARED JAY, CYANOLYCA VZRIDZCYANA MERIDA JOHN WILLIAM HARDY Previously, I have indicated (Kansas Sci. Bull., 42: 113, 1961) that the New World jays could be systematically grouped in two tribes on the basis of a variety of morphological and behavioral characteristics. I subsequently demonstrated (Occas. Papers Adams Ctr. Ecol. Studies, No. 11, 1964) the relationships between Cyanolyca and Aphelocoma. The tribe Aphelocomini, comprising the currently recognized genera Aphelocoma and Cyanolyca, may be characterized as follows: pattern and ornamen- tation of head simple, consisting of a dark mask, pale superciliary lineation, and no tendency for a crest; tail plain-tipped; vocal repertoire of one to three basic com- ponents, including alarm calls, flock-social calls, or both, that are nasal, querulous, and upwardly or doubly inflected. In contrast, the Cyanocoracini may be charac- tized as follows: pattern of head complex, consisting of triangular cheek patch, super- ciliary spot, and tendency for a crest; tail usually pale-tipped; vocal repertoire usu- ally complex, commonly including a downwardly inflected cuwing call and never an upwardly inflected, nasal querulous call (when repertoire is limited it almost always includes the cazo!ingcall). None of the four Mexican aphelocomine jays has more than three basic calls in its vocal repertoire. There are two exclusively South American species of CyanuZyca (C. viridicyana and C. pulchra). On the basis of the consistency with which the Mexican and Central American speciesof this genus hew to a general pattern of vocalizations as I described it for the tribe, I inferred (1964 op. -

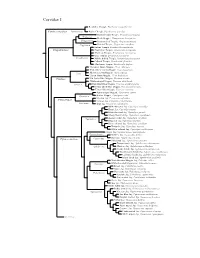

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

Birds of Davis Creek Regional Park Thank You to the Following Photographers Who Supplied Pictures Taken at Davis Creek Regional Park

Birds of Davis Creek Regional Park Thank You to the following photographers who supplied pictures taken at Davis Creek Regional Park: Jeff Bleam, Ernest A. Ross, Steven Siegel, Tim Torell, Taylor James, Greg Scyphers, Jon Becknell, Sara Danta & Jane Thompson Future picture submissions can be sent to: [email protected] Thank You! Bird ID, Range Info. and Fun Facts from www.allaboutbirds.org Western Tanager (Piranga ludoviciana) ID: Orange-red head, yellow body and coal-black wings, back and tail. Short, thick-based bill and medium-length tail. Size: Between sparrow and robin. Fun Fact: While most red birds owe their redness to a variety of plant pigments known as carotenoids, the Western Tanager gets its scarlet head feathers from a rare pigment called rhodoxanthin. Unable to make this substance in their own bodies, Western Tanagers probably obtain it from insects in their diet. (allaboutbirds.org) Pacific Wren (Troglodytes pacificus) ID: Brown overall with darker brownish- black barring on the wings, tail and belly. Face is also brown with a slight pale mark over the eyebrow. Short wings, stubby tail and a thin bill. Size: Sparrow-sized or smaller. Fun Fact: Male Pacific Wrens build multiple nests within their territory. During courtship, males lead the female around to each nest and the female chooses which nest to use. (allaboutbirds.org) Bewick’s Wren (Thryomanes bewickii) ID: Slender body with a slender, long bill that is slightly downcurved. Back and wings are plain brown; underparts gray- white; and the long tail is barred with black and tipped with white spots. Long, brow-like white stripe over the eye.