The Brown Jay's Furcular Pouch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Engelsk Register

Danske navne på alverdens FUGLE ENGELSK REGISTER 1 Bearbejdning af paginering og sortering af registret er foretaget ved hjælp af Microsoft Excel, hvor det har været nødvendigt at indlede sidehenvisningerne med et bogstav og eventuelt 0 for siderne 1 til 99. Tallet efter bindestregen giver artens rækkefølge på siden. -

Acacia, Cattle and Migratory Birds in Southeastern Mexico

Biological Conservation 80 (1997) 235-247 © 1997 Elsevier Science Ltd All rights reserved. Printed in Great Britain PII: S0006-3207(96)00137- 1 0006-3207/97 $17.00 + 0.00 ELSEVIER ACACIA, CATTLE AND MIGRATORY BIRDS IN SOUTHEASTERN MEXICO Russell Greenberg,* Peter Bichier & John Sterling Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center, National Zoological Park, Washington, DC 20008, USA (Accepted 11 July 1996) Abstract of forest-dependent migratory birds (Askins et al., Acacia pennatula groves in mid-elevation valleys of 1990). However, the new tropical landscape is usually a southern Mexico supported both the highest density and mosaic of grassland, savanna, ribbons of riparian vege- diversity of migratory birds compared to other habitats in tation and small patches of woods. The wooded habi- the region. In addition, we found the highest numbers for tats, in particular, can support an abundance of over half of the common migratory species. Despite the migratory birds (Powell et al., 1992; Warkentin et al., high degree of leaf loss during the late winter, acacia 1995). One possible strategy for increasing habitat for groves do not experience greater declines in insectivorous migratory birds is the promotion of silvopastoral sys- migratory bird populations than other local habitats. tems which integrate tree management with cattle pro- Color-marked individuals of canopy species had a strong duction on grazing lands. tendency to remain resident within a single acacia grove During several years of censusing birds on the Car- throughout the winter. Management of native acacias on ibbean slope of Chiapas, we discovered that managed subtropical rangelands for wood products, fodder, and soil patches of Acacia pennatula (Schlecht & Cham.) Benth improvement would probably directly and indirectly bene- support particularly high densities of migratory birds. -

Gear for a Big Year

APPENDIX 1 GEAR FOR A BIG YEAR 40-liter REI Vagabond Tour 40 Two passports Travel Pack Wallet Tumi luggage tag Two notebooks Leica 10x42 Ultravid HD-Plus Two Sharpie pens binoculars Oakley sunglasses Leica 65 mm Televid spotting scope with tripod Fossil watch Leica V-Lux camera Asics GEL-Enduro 7 trail running shoes GoPro Hero3 video camera with selfie stick Four Mountain Hardwear Wicked Lite short-sleeved T-shirts 11” MacBook Air laptop Columbia Sportswear rain shell iPhone 6 (and iPhone 4) with an international phone plan Marmot down jacket iPod nano and headphones Two pairs of ExOfficio field pants SureFire Fury LED flashlight Three pairs of ExOfficio Give- with rechargeable batteries N-Go boxer underwear Green laser pointer Two long-sleeved ExOfficio BugsAway insect-repelling Yalumi LED headlamp shirts with sun protection Sea to Summit silk sleeping bag Two pairs of SmartWool socks liner Two pairs of cotton Balega socks Set of adapter plugs for the world Birding Without Borders_F.indd 264 7/14/17 10:49 AM Gear for a Big Year • 265 Wildy Adventure anti-leech Antimalarial pills socks First-aid kit Two bandanas Assorted toiletries (comb, Plain black baseball cap lip balm, eye drops, toenail clippers, tweezers, toothbrush, REI Campware spoon toothpaste, floss, aspirin, Israeli water-purification tablets Imodium, sunscreen) Birding Without Borders_F.indd 265 7/14/17 10:49 AM APPENDIX 2 BIG YEAR SNAPSHOT New Unique per per % % Country Days Total New Unique Day Day New Unique Antarctica / Falklands 8 54 54 30 7 4 100% 56% Argentina 12 435 -

Section IV – Guideline for the Texas Priority Species List

Section IV – Guideline for the Texas Priority Species List Associated Tables The Texas Priority Species List……………..733 Introduction For many years the management and conservation of wildlife species has focused on the individual animal or population of interest. Many times, directing research and conservation plans toward individual species also benefits incidental species; sometimes entire ecosystems. Unfortunately, there are times when highly focused research and conservation of particular species can also harm peripheral species and their habitats. Management that is focused on entire habitats or communities would decrease the possibility of harming those incidental species or their habitats. A holistic management approach would potentially allow species within a community to take care of themselves (Savory 1988); however, the study of particular species of concern is still necessary due to the smaller scale at which individuals are studied. Until we understand all of the parts that make up the whole can we then focus more on the habitat management approach to conservation. Species Conservation In terms of species diversity, Texas is considered the second most diverse state in the Union. Texas has the highest number of bird and reptile taxon and is second in number of plants and mammals in the United States (NatureServe 2002). There have been over 600 species of bird that have been identified within the borders of Texas and 184 known species of mammal, including marine species that inhabit Texas’ coastal waters (Schmidly 2004). It is estimated that approximately 29,000 species of insect in Texas take up residence in every conceivable habitat, including rocky outcroppings, pitcher plant bogs, and on individual species of plants (Riley in publication). -

The Puzzling Vocal Repertoire of the South American Collared Jay, Cyanolyca Iridicyana Merida

THE PUZZLING VOCAL REPERTOIRE OF THE SOUTH AMERICAN COLLARED JAY, CYANOLYCA VZRIDZCYANA MERIDA JOHN WILLIAM HARDY Previously, I have indicated (Kansas Sci. Bull., 42: 113, 1961) that the New World jays could be systematically grouped in two tribes on the basis of a variety of morphological and behavioral characteristics. I subsequently demonstrated (Occas. Papers Adams Ctr. Ecol. Studies, No. 11, 1964) the relationships between Cyanolyca and Aphelocoma. The tribe Aphelocomini, comprising the currently recognized genera Aphelocoma and Cyanolyca, may be characterized as follows: pattern and ornamen- tation of head simple, consisting of a dark mask, pale superciliary lineation, and no tendency for a crest; tail plain-tipped; vocal repertoire of one to three basic com- ponents, including alarm calls, flock-social calls, or both, that are nasal, querulous, and upwardly or doubly inflected. In contrast, the Cyanocoracini may be charac- tized as follows: pattern of head complex, consisting of triangular cheek patch, super- ciliary spot, and tendency for a crest; tail usually pale-tipped; vocal repertoire usu- ally complex, commonly including a downwardly inflected cuwing call and never an upwardly inflected, nasal querulous call (when repertoire is limited it almost always includes the cazo!ingcall). None of the four Mexican aphelocomine jays has more than three basic calls in its vocal repertoire. There are two exclusively South American species of CyanuZyca (C. viridicyana and C. pulchra). On the basis of the consistency with which the Mexican and Central American speciesof this genus hew to a general pattern of vocalizations as I described it for the tribe, I inferred (1964 op. -

The White-Throated Magpie-Jay

THE WHITE-THROATED MAGPIE-JAY BY ALEXANDER F. SKUTCH ORE than 15 years have passed since I was last in the haunts of the M White-throated Magpie-Jay (Calocitta formosa) . During the years when I travelled more widely through Central America I saw much of this bird, and learned enough of its habits to convince me that it would well repay a thorough study. Since it now appears unlikely that I shall make this study myself, I wish to put on record such information as I gleaned, in the hope that these fragmentary notes will stimulate some other bird- watcher to give this jay the attention it deserves. A big, long-tailed bird about 20 inches in length, with blue and white plumage and a high, loosely waving crest of recurved black feathers, the White-throated Magpie-Jay is a handsome species unlikely to be confused with any other member of the family. Its upper parts, including the wings and most of the tail, are blue or blue-gray with a tinge of lavender. The sides of the head and all the under plumage are white, and the outer feathers of the strongly graduated tail are white on the terminal half. A narrow black collar crosses the breast and extends half-way up each side of the neck, between the white and the blue. The stout bill and the legs and feet are black. The sexes are alike in appearance. The species extends from the Mexican states of Colima and Puebla to northwestern Costa Rica. A bird of the drier regions, it is found chiefly along the Pacific coast from Mexico southward as far as the Gulf of Nicoya in Costa Rica. -

Distribution Habitat and Social Organization of the Florida Scrub Jay

DISTRIBUTION, HABITAT, AND SOCIAL ORGANIZATION OF THE FLORIDA SCRUB JAY, WITH A DISCUSSION OF THE EVOLUTION OF COOPERATIVE BREEDING IN NEW WORLD JAYS BY JEFFREY A. COX A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1984 To my wife, Cristy Ann ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank, the following people who provided information on the distribution of Florida Scrub Jays or other forms of assistance: K, Alvarez, M. Allen, P. C. Anderson, T. H. Below, C. W. Biggs, B. B. Black, M. C. Bowman, R. J. Brady, D. R. Breininger, G. Bretz, D. Brigham, P. Brodkorb, J. Brooks, M. Brothers, R. Brown, M. R. Browning, S. Burr, B. S. Burton, P. Carrington, K. Cars tens, S. L. Cawley, Mrs. T. S. Christensen, E. S. Clark, J. L. Clutts, A. Conner, W. Courser, J. Cox, R. Crawford, H. Gruickshank, E, Cutlip, J. Cutlip, R. Delotelle, M. DeRonde, C. Dickard, W. and H. Dowling, T. Engstrom, S. B. Fickett, J. W. Fitzpatrick, K. Forrest, D. Freeman, D. D. Fulghura, K. L. Garrett, G. Geanangel, W. George, T. Gilbert, D. Goodwin, J. Greene, S. A. Grimes, W. Hale, F. Hames, J. Hanvey, F. W. Harden, J. W. Hardy, G. B. Hemingway, Jr., 0. Hewitt, B. Humphreys, A. D. Jacobberger, A. F. Johnson, J. B. Johnson, H. W. Kale II, L. Kiff, J. N. Layne, R. Lee, R. Loftin, F. E. Lohrer, J. Loughlin, the late C. R. Mason, J. McKinlay, J. R. Miller, R. R. Miller, B. -

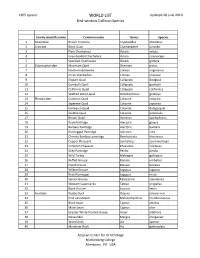

WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-Window Collision Species

1305 species WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-window Collision Species Family scientific name Common name Genus Species 1 Tinamidae Brown Tinamou Crypturellus obsoletus 2 Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor 3 Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula 4 Grey-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps 5 Speckled Chachalaca Ortalis guttata 6 Odontophoridae Mountain Quail Oreortyx pictus 7 Northern Bobwhite Colinus virginianus 8 Crested Bobwhite Colinus cristatus 9 Elegant Quail Callipepla douglasii 10 Gambel's Quail Callipepla gambelii 11 California Quail Callipepla californica 12 Spotted Wood-quail Odontophorus guttatus 13 Phasianidae Common Quail Coturnix coturnix 14 Japanese Quail Coturnix japonica 15 Harlequin Quail Coturnix delegorguei 16 Stubble Quail Coturnix pectoralis 17 Brown Quail Synoicus ypsilophorus 18 Rock Partridge Alectoris graeca 19 Barbary Partridge Alectoris barbara 20 Red-legged Partridge Alectoris rufa 21 Chinese Bamboo-partridge Bambusicola thoracicus 22 Copper Pheasant Syrmaticus soemmerringii 23 Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus 24 Grey Partridge Perdix perdix 25 Wild Turkey Meleagris gallopavo 26 Ruffed Grouse Bonasa umbellus 27 Hazel Grouse Bonasa bonasia 28 Willow Grouse Lagopus lagopus 29 Rock Ptarmigan Lagopus muta 30 Spruce Grouse Falcipennis canadensis 31 Western Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus 32 Black Grouse Lyrurus tetrix 33 Anatidae Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis 34 Pink-eared Duck Malacorhynchus membranaceus 35 Black Swan Cygnus atratus 36 Mute Swan Cygnus olor 37 Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons 38 -

Birds of the South Texas Brushlands

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE BIRDS of the BY JOHN C. ARVIN SOUTH TEXAS BRUSHLANDS A Field Checklist June 2007 TPWD receives federal assistance from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and other federal agencies. TPWD is therefore subject to Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, in addition to state anti-discrimination laws. TPWD will comply with state and federal laws prohibiting discrimination based on race, color, national origin, age, sex or disability. If you believe that you have been discriminated against in any TPWD program, activity or event, you may contact the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Federal Assistance, 4401 N. Fairfax Drive, Mail Stop: MBSP-4020, Arlington, VA 22203, Attention: Civil Rights Coordinator for Public Access. Birds of the South Texas Brushlands: A Field Checklist Second Edition INTRODUCTION he South Texas Brushlands ecoregion, also known as the Rio Grande Plain or Tamaulipan Brushlands, consists of the southern one fifth or so of the state, south of the Edwards TPlateau and west of the San Antonio River. It includes the Rio Grande Valley from about Del Rio to where the river empties into the Gulf of Mexico and the lower coast of Texas from Baffin Bay southward. This region is flat to gently rolling with a few higher hills and cliffs along the Rio Grande. This vast plain is covered mostly with a dense growth of low thorny trees, shrubs and cacti. -

Mate-Guarding in Siberian Jay (Perisoreus Infaustus)

Mate-guarding in Siberian jay (Perisoreus infaustus) Mate-guarding hos Lavskrikor (Perisoreus infaustus) Leo Ruth Faculty of Health, Science and Technology Biology Independent Research Project 15 hp Supervisor: Björn Arvidsson and Michael Griesser Examinor: Larry Greenberg 26/08-16 Serial number: 16:102 Abstract Mate-guarding is performed by many monogamous species, a method used by individuals to physically prevent competitors of the same sex from mating with their partners. This behaviour is most often displayed during the fertile period (i.e. when females can be fertilized). In this study I focused on the genetically and socially monogamous species, the Siberian jay (Perisoreus infaustus), in which I observed mate-guarding behaviour. The Siberian jays did change their behaviour and increased their aggression in the fertile period, a sign of mate-guarding. This result also suggests that even socially and genetically monogamous species do increase their aggression during the fertile period. This indicates that fidelity still requires an investment in mate-guarding to limit extra-pair mating opportunities. Mate- guarding should then be possible to find in species where there is at least a theoretical opportunity for extra-pair matings. Sammanfattning Mate-guarding är en metod använd utav många monogama arter, metoden används för att fysiskt hålla konkurrenter utav samma kön borta ifrån sin partner för att försäkra sin egen parning. Denna metod beskådas oftast under tiden honan är fertil. I denna studie fokuserade jag på den genetiska och sociala monogama arten Lavskrika(Perisoreus infaustus) där jag observerade mate-guarding beteende. Lavskrikans beteende förändrades mellan perioden då honan icke var receptiv och hon var fertil, aggressionen ökade för båda könen under den fertila perioden vilket är ett tecken utav mate-guarding beteende. -

Bird Species I Have Seen World List

bird species I have seen U.K tally: 279 US tally: 393 Total world: 1,496 world list 1. Abyssinian ground hornbill 2. Abyssinian longclaw 3. Abyssinian white-eye 4. Acorn woodpecker 5. African black-headed oriole 6. African drongo 7. African fish-eagle 8. African harrier-hawk 9. African hawk-eagle 10. African mourning dove 11. African palm swift 12. African paradise flycatcher 13. African paradise monarch 14. African pied wagtail 15. African rook 16. African white-backed vulture 17. Agami heron 18. Alexandrine parakeet 19. Amazon kingfisher 20. American avocet 21. American bittern 22. American black duck 23. American cliff swallow 24. American coot 25. American crow 26. American dipper 27. American flamingo 28. American golden plover 29. American goldfinch 30. American kestrel 31. American mag 32. American oystercatcher 33. American pipit 34. American pygmy kingfisher 35. American redstart 36. American robin 37. American swallow-tailed kite 38. American tree sparrow 39. American white pelican 40. American wigeon 41. Ancient murrelet 42. Andean avocet 43. Andean condor 44. Andean flamingo 45. Andean gull 46. Andean negrito 47. Andean swift 48. Anhinga 49. Antillean crested hummingbird 50. Antillean euphonia 51. Antillean mango 52. Antillean nighthawk 53. Antillean palm-swift 54. Aplomado falcon 55. Arabian bustard 56. Arcadian flycatcher 57. Arctic redpoll 58. Arctic skua 59. Arctic tern 60. Armenian gull 61. Arrow-headed warbler 62. Ash-throated flycatcher 63. Ashy-headed goose 64. Ashy-headed laughing thrush (endemic) 65. Asian black bulbul 66. Asian openbill 67. Asian palm-swift 68. Asian paradise flycatcher 69. Asian woolly-necked stork 70.