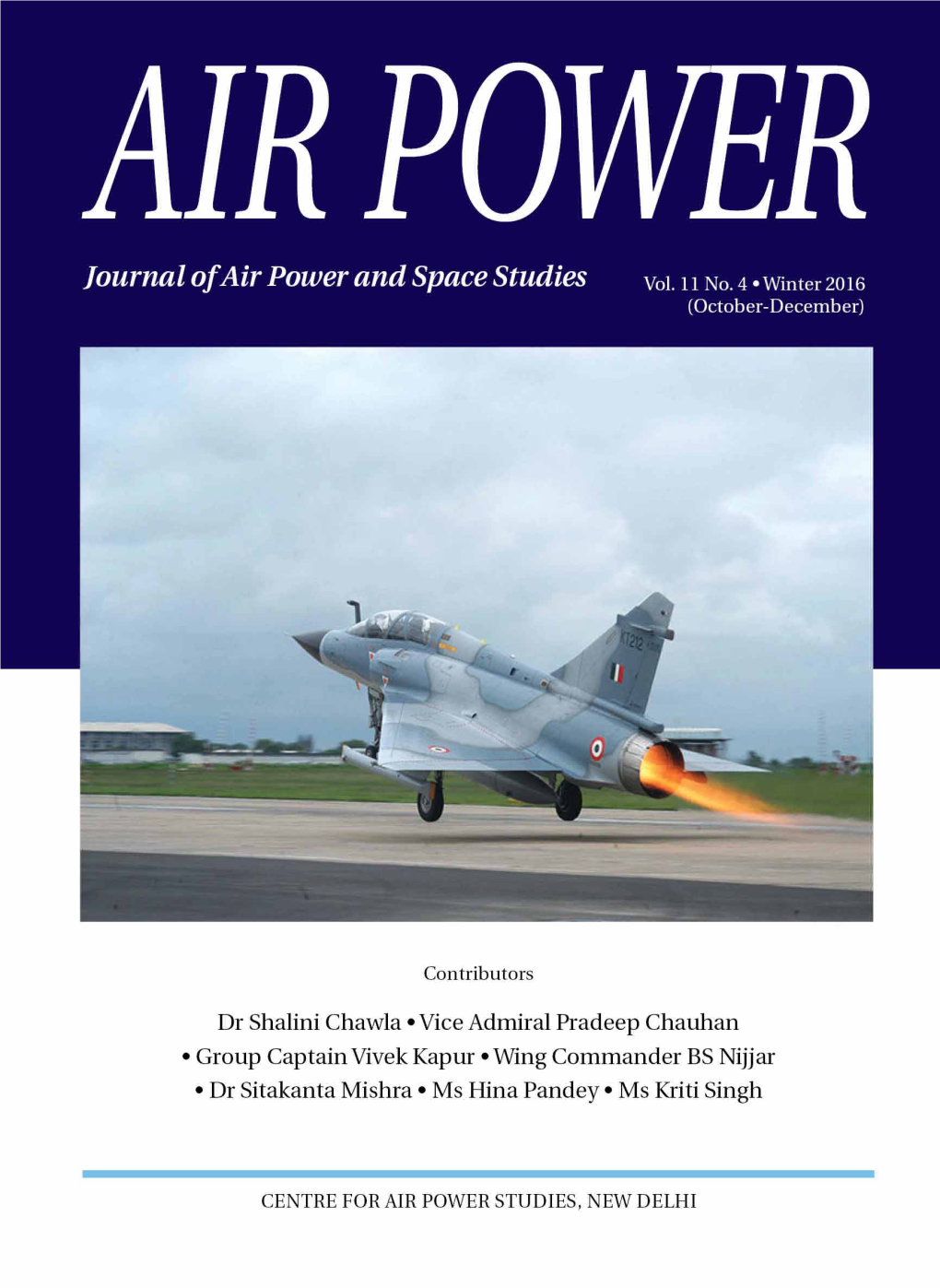

October-December)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Community on Kargil Conflict, South Asian Studies, 28-I

South Asian Studies A Research Journal of South Asian Studies Vol. 28, No. 1, January – June 2013, pp.85-96 International Community on Kargil Conflict Mussarat Javaid Cheema University of the Punjab, Lahore ABSTRACT In February 1999 Pakistan and India, through Lahore Declaration that was signed between the Prime Ministers of two countries, declared to resolve the continuing decades-long conflict between the two countries. But after some months of the Declaration both countries were involved into a horrible episode of conflict that virtually brought the world on the brink of first clash between two nuclear states. Getting control of a main route to Kargil by Kashmiri militants led to a great episode of conflict between India and Pakistan. This episode was significant because of the fact that both countries had entered into nuclear club just one year ago and this episode proved to be the first confrontation between two armies equipped with atomic arsenal. How this conflict arose and how international community saw this incident is the focus of this paper. The Paper will also examine how the external political factors played a critical role in the unfolding of the Kargil conflict. The impact of this episode on the policies of international powers will also be examined. In the light of this analysis of the events the impact of this episode in the conflict resolution in South Asia will also be observed. KEY WORDS: Kashmir, Kargil war, conflict resolution, India-Pakistan relations, International reaction, nuclear states Introduction A comprehensive definition describes conflict as a number of forms of politicized violence, inter-state war, insurgency and guerrilla war, terrorism and sectarian or communal rioting. -

Kargil Operation 1999

KARGIL OPERATION 1999 The Kargil War, also known as the Kargil conflict was an armed conflict between India and Pakistan that took place between May and July 1999 in the Kargil district of Kashmir and elsewhere along the Line of Control (LOC). In India, the conflict is also referred to as Operation Vijay which was the name of the Indian operation to clear the Kargil sector.The war is the most recent example of high-altitude warfare in mountainous terrain, and as such posed significant logistical problems for the combating sides.The cause of the war was the infiltration of Pakistani soldiers disguised as Kashmiri militants into positions on the Indian side of the LOC which serves as the border between the two states. During the initial stages of the war, Pakistan blamed the fighting entirely on independent Kashmiri insurgents, but documents left behind by casualties and later statements by Pakistan's Prime Minister and Chief of Army Staff showed involvement of Pakistani paramilitary forces led by General Ashraf Rashid. The Indian Army, later supported by the Indian Air Force, recaptured a majority of the positions on the Indian side of the LOC infiltrated by the Pakistani troops and militants. Facing international diplomatic opposition, the Pakistani forces withdrew from the remaining Indian positions along the LOC. There were three major phases to the Kargil War. First, Pakistan infiltrated forces into the Indian-controlled section of Kashmir and occupied strategic locations enabling it to bring NH1 within range of its artillery fire. The next stage consisted of India discovering the infiltration and mobilising forces to respond to it. -

Realignment and Indian Air Power Doctrine

Realignment and Indian Airpower Doctrine Challenges in an Evolving Strategic Context Dr. Christina Goulter Prof. Harsh Pant Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, Air Force, Air Education and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. This article may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. If it is reproduced, the Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs requests a courtesy line. ith a shift in the balance of power in the Far East, as well as multiple chal- Wlenges in the wider international security environment, several nations in the Indo-Pacific region have undergone significant changes in their defense pos- tures. This is particularly the case with India, which has gone from a regional, largely Pakistan-focused, perspective to one involving global influence and power projection. This has presented ramifications for all the Indian armed services, but especially the Indian Air Force (IAF). Over the last decade, the IAF has been trans- forming itself from a principally army-support instrument to a broad spectrum air force, and this prompted a radical revision of Indian aipower doctrine in 2012. It is akin to Western airpower thought, but much of the latest doctrine is indigenous and demonstrates some unique conceptual work, not least in the way maritime air- power is used to protect Indian territories in the Indian Ocean and safeguard sea lines of communication. Because of this, it is starting to have traction in Anglo- American defense circles.1 The current Indian emphases on strategic reach and con- ventional deterrence have been prompted by other events as well, not least the 1999 Kargil conflict between India and Pakistan, which demonstrated that India lacked a balanced defense apparatus. -

Air Wing Specialised Subjects SD-SW

1 INDEX SL Subject Page No No 1. General Service Knowledge 09-31 2. Air Campaigns 32-44 3. Aircraft Recognition 45-67 4. Modern Trends 68-73 5. Principles of Flight 74-104 6. Airmanship 105-147 7. Navigation 148-161 8. Meteorology 162-181 9. Aero Engines 182-198 10. Airframe 199-215 11. Instruments 216-227 12. Aircraft Particulars 228-234 13. Aero Modeling 235-246 2 CHAPTER - I General Service Knowledge Sl No Code Subject Page No 1 GSK-1 Development of Aviation 10-14 2 GSK-2 History of IAF 15-18 3 GSK-3 Organisation of IAF 19-22 4 GSK-4 Branches of the IAF 23-24 5 GSK-5 Modes of Entry in the IAF 25-27 6 GSK-6 Career in the IAF as an Officer/ Airman 28-31 CHAPTER - II Air Campaigns (AC) Sl No Code Subject Page No 1 AC -1 Indo Pak War 1971 33-36 2 AC -2 Op Safed Sagar 37-39 3 AC -3 Famous Air Heroes 40-43 4 AC -4 Motivational Movies 44 CHAPTER - III Aircraft Recognition (ACR) Sl No Code Subject Page No 1 AC R-1 Fighters 46-51 2 ACR -2 Transports 52-57 3 AC R-3 Helicopters 58-62 4 ACR -4 Foreign Aircraft 63-67 CHAPTER - IV Modern Trends (MT) Sl No Code Subject Page No 1 MT-1 Modern Trends 69-73 CHAPTER - V Principles of Flight (PF) Sl No Code Subject Page No 1 PF-1 Introduction 75-76 2 PF-2 Laws of Motion 77-80 3 PF-3 Glossary of Terms 81-83 4 PF-4 Bernoulli’s Theorem and Venturi Effect 84-86 5 PF-5 Aerofoil 87-89 6 PF-6 Forces on an Aircraft 90-91 7 PF-7 Lift & Drag 92-93 8 PF-8 Flaps & Slats 94-97 9 PF-9 Stalling 98-100 10 PF-10 Thrust 101-104 CHAPTER - VI Airmanship (AR) Sl No Code Subject Page No 1 AR-1 Introduction 106-110 2 AR-2 Airfield -

Kargil Vijay Diavs ……

KARGIL VIJAY DIAVS …… Kargil War Part of the Indo-Pakistani wars and conflicts and the Kashmir conflict ❖ Period of Kargil War : Date3 May – 26 July 1999 (2 months, 3 weeks and 2 days) ❖Location : Kargil district, Jammu and Kashmir, India ❖Result Decisive : Indian victory ❖India regains possession of Kargil ❖Territorial changes - Status quo ante bellum Kargil War : Strength INDA PAKISTAN 30,000 5000 Kargil War :Commanders and leaders INDIA PAKISTAN K. R. Narayanan( President of India) Muhammad Rafiq Tarar( President of Pakistan) Atal Bihari Vajpayee(Prime Minister of India) Nawaz Sharif(Prime Minister of Pakistan) Gen Ved Prakash Malik (Chief of the Army Staff) Gen Pervez Musharraf( Chief of the Army Staff) Lt Gen Chandra Shekhar(Vice Chief of the Army Staff) Lt GenMuhammad Aziz Khan(Chief of the General Staff) ACM Anil Yashwant Tipnis(Chief of the Air Staff) ACM Pervaiz Mehdi Qureshi Chief of the Air Staff) Kargil War :Casualties and losses Indian official figures Independent figures 527 killed 700 casualties 1,363 wounded Pakistani figures 1 1 Pilot (K Nachiketa) held as prisoner of war 453 killed (Pakistan army claim) 1 fighter jet shot down Other Pakistani claims 1 fighter jet crashed 357 killed and 665+ wounded (according to Pervez Musharra) 1 helicopter shot down 2,700–4,000 killed (according to Nawaz Sharif) Pakistani claims Indian claims 1,600 (as claimed by Musharraf) 737-1,200 casualties1,000+ wounded Kargil War ❖The Kargil War, also known as the Kargil conflict, was an armed conflict between India and Pakistan that took place between May and July 1999 in the Kargil district of Kashmir and elsewhere along the Line of Control (LOC). -

Sainik Cover 1

2019 1-15 August Vol 66 No 15 ` 5 SAINIK Samachar Remember - Rejoice - Renew Kargil Vijay Diwas Celebrations Raksha Mantri Shri Rajnath Singh signing MoU with Defence Minister of Mozambique, Mr Atanasio Salvador M’tumuke in capital Maputo on July 29, 2019. pic: DPR Photo Division The Union Minister for Defence, Shri Rajnath Singh being briefed on the working of Dashboard of Department Defence Production (www.ddpdashboard.gov.in) by the Secretary (Defence Production), Dr Ajay Kumar, in New Delhi on July 25, 2019 In This Issue Since 1909 PresidentBIRTH Pays ANNIVERSARY Homage CELEBRATIONS to Martyrs of 4 Kargil War (Initially published as FAUJI AKHBAR) Vol. 66 q No 15 10 - 24 Shravana 1941 (Saka) 1-15 August 2019 The journal of India’s Armed Forces published every fortnight in thirteen languages including Hindi & English on behalf of Ministry of Defence. It is not necessarily an organ for the expression of the Government’s defence policy. The published items represent the views of respective writers and correspondents. Editor-in-Chief Ruby Thinda Sharma PM addresses Kargil Raksha Mantri pays Senior Editor Manoj Tuli Vijay Diwas… 6 homage to Martyrs… 8 Sub Editor Sub Maj KC Sahu Sub Maj Baiju G Coordination Kunal Kumar Business Manager Dhirendra Kumar Our Correspondents DELHI: Lt Col M Vaishnava (Offg.); Capt DK Sharma VSM; Gp Capt Anupam Banerjee; Divyanshu Kumar; BENGALURU: Guru Prasad HL; CHANDIGARH: Anil Gaur; CHENNAI: M Ponnein Selvan; GANDHINAGAR: Wg Cdr Puneet Chadha; GUWAHATI: Lt Col P Khongsai; IMPHAL: Lt Col M Vaishnava; JALANDHAR -

Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs 2018 Qtr3

Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs FALL 2018 Volume 1, No. 1 Senior Leader Perspective Opening the Aperture Advancing US Strategic Priorities in the Indo-Pacific Region ❘ 3 Gen Herbert J. “Hawk” Carlisle, USAF, Retired Views & Features A Short History of US Involvement in the Indo-Pacific ❘ 14 Christopher L. Kolakowski Realignment and Indian Air Power Doctrine Challenges in an Evolving Strategic Context ❘ 21 Dr. Christina Goulter Prof. Harsh Pant US Military Liberty Restrictions in Okinawa —Falling on Deaf Ears? ❘ 45 Maj John C. Wright, USAF Evolving Dynamics in the Indo-Pacific Deliberating India’s Position ❘ 53 Pooja Bhatt Ecuador’s Leveraging of China to Pursue an Alternative Political and Development Path ❘ 79 R. Evan Ellis Editorial Advisors Dr. Ernest Allan Rockwell, Director, Air University Press Gen Herbert J. “Hawk” Carlisle, USAF, Retired; President and CEO, National Defense Industrial Association Dr. Matthew C. Stafford, Chief Academic Officer, Air Education and Training Command Col Jeff Donnithorne, USAF, PhD, Chief Academic Officer, Air University Reviewers Gp Capt Nasim Abbas Dr. Jessica Jordan Instructor, Air War College Assistant Professor, Air Force Culture and Language Center Pakistan Air Force Air University Dr. Sascha-Dominik “Dov” Bachmann Mr. Chris Kolakowski Assoc. Prof. & Director, Centre of Director Conflict, Rule of Law and Society The General Douglas MacArthur Memorial Bournemouth University (United Kingdom) Dr. Carlo Kopp Dr. Lewis Bernstein Lecturer Historian, retired Monash University (Australia) United States Army Lt Col Scott D. McDonald, USMC Dr. Paul J. Bolt Military Professor Professor, Political Science Daniel K. Inouye Asia–Pacific Center for Security Studies US Air Force Academy Dr. Brendan S. -

South Asia's Lessons, Evolving Dynamics, and Trajectories

South Asia’s Lessons, Evolving Dynamics, and Trajectories Edited by Sameer Lalwani and Hannah Haegeland South Asia’s Lessons, Evolving Dynamics, and Trajectories Edited by Sameer Lalwani and Hannah Haegeland JANUARY 2018 © Copyright 2018 by the Stimson Center. All rights reserved. Printed in Washington, D.C. ISBN 978-0-9997659-0-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017919496 Stimson Center 1211 Connecticut Avenue, NW 8th Floor Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. Visit www.stimson.org for more information about Stimson’s research. Investigating Crises: South Asia’s Lessons, Evolving Dynamics, and Trajectories CONTENTS Preface . 7 Key Terms and Acronyms . 9 Introduction . 11 Sameer Lalwani Anatomy of a Crisis: Explaining Crisis Onset in India-Pakistan Relations . 23 Sameer Lalwani & Hannah Haegeland Organizing for Crisis Management: Evaluating India’s Experience in Three Case Studies . .57 Shyam Saran Conflict Resolution and Crisis Management: Challenges in Pakistan-India Relations . 75 Riaz Mohammad Khan Intelligence, Strategic Assessment, and Decision Process Deficits: The Absence of Indian Learning from Crisis to Crisis . 97 Saikat Datta Self-Referencing the News: Media, Policymaking, and Public Opinion in India-Pakistan Crises . 115 Ruhee Neog Crisis Management in Nuclear South Asia: A Pakistani Perspective . 143 Zafar Khan China and Crisis Management in South Asia . 165 Yun Sun & Hannah Haegeland Crisis Intensity and Nuclear Signaling in South Asia . 187 Michael Krepon & Liv Dowling New Horizons, New Risks: A Scenario-based Approach to Thinking about the Future of Crisis Stability in South Asia . 221 Iskander Rehman New Challenges for Crisis Management . 251 Michael Krepon Contributors . 265 Contents 6 PREFACE With gratitude and pride I present Stimson’s latest South Asia Program book, Investigating Crises: South Asia’s Lessons, Evolving Dynamics, and Trajectories. -

Kargil Revisited: Air Operations in a High Altitude Conflict

Kargil Revisited: Air Operations in a High Altitude Conflict A Subramanian Editor's Note: In the interest of the free exchange of views and in order to encourage individual writing on important national security issues, the following article by Air Cmde A Subramanian has been published in full. However, it must be pointed out that there are divergent views on the Army-Air Force issues taken up by the author. In this light General V P Malik, former Chief of the Army Staff’s book titled Kargil: From Surprise to Victory presents a completely different perspective. he Kargil conflict treads a very thin line between limited and sub- conventional conflict because of the manner in which the infiltration was Tconducted by ‘regulars’ of the Pakistan Northern Light Infantry (NLI) supported by a sprinkling of jehadis, Mujahideen and foreign terrorists (FTs), and the diverse manner in which the Indian Army and Indian Air Force (IAF) reacted to the intrusion. The Indian Army responded to the intrusion in a purely conventional response to a limited conflict scenario at high altitude in terms of forces employed and tactics followed. However, the IAF fought in an ‘unconventional’ manner in terms of the political constraints imposed on it in the form of stringent Rules of Engagement and terrain imperatives that had never been encountered before, and their associated impact on targeting. Innovative and never-used-before tactics had to be employed and that is why the utilisation of air power merits attention as part of a study of air power employment in ‘unconventional warfare’ , because the Kargil War was truly unconventional in many ways from an air power perspective, both strategically and tactically. -

Seminar Report 20 YEARS AFTER KARGIL CONFLICT

Seminar Report 20 YEARS AFTER KARGIL CONFLICT July 13, 2019 Seminar Coordinator: Colonel Sunil Gupta Rapporteur: Kanchana Ramanujam and Anashwara Ashok Centre for Land Warfare Studies RPSO Complex, Parade Road, Delhi Cantt, New Delhi-110010 Phone: 011-25691308; Fax: 011-25692347; Army No.: 33098 email: [email protected]; website: www.claws.in The Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS), New Delhi, is an independent think tank dealing with contemporary issues of national security and conceptual aspects of land warfare, including conventional and sub-conventional conflicts and terrorism. CLAWS conducts research that is futuristic in outlook and policy-oriented in approach. CLAWS Vision: To establish as a leading Centre of Excellence, Research and Studies on Military Strategy & Doctrine, Land Warfare, Regional & National Security, Military Technology and Human Resource. © 2019, Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS), New Delhi All rights reserved The views expressed in this report are sole responsibility of the speaker(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India, or Integrated Headquarters of MoD (Army) or Centre for Land Warfare Studies. The content may be reproduced by giving due credit to the speaker(s) and the Centre for Land Warfare Studies, New Delhi. Printed in India by Bloomsbury Publishing India Pvt. Ltd. DDA Complex LSC, Building No. 4, 2nd Floor Pocket 6 & 7, Sector – C Vasant Kunj, New Delhi 110070 www.bloomsbury.com CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 DETAILED REPORT 11 Aim 7 Modalities of Conduct 7 Chair 7 Opening Remarks by CLAWS Director 8 Keynote Address by Chief of the Army Staff 9 Special Address by General VP Malik Ex Chief of Army Staff 12 Special Address by General NC Vij, Ex Chief of the Army Staff and Ex Director General of Military Operations 14 Special Address by Lieutenant General Mohinder Puri, Ex-General Officer Commanding Kargil Division During Operation VIJAY and Ex Deputy Chief of the Army Staff 17 SESSION I. -

REVISION CAPF 2019 Compiled and Edited by VIKRANT S

DNYANADEEP IAS SUPER SERIES REVISION CAPF 2019 Compiled and Edited by VIKRANT S. MORE (IDES) RAJNIKANT D. MOHITE HIGHLIGHTS ➢ Complete Strategy for Paper 2 with Analysis ➢ Probable topics for Paper 2 ➢ Current Affairs and Static part covered as per analysis of previous year question papers • Budget and Economic survey highlights with newly launched schemes • Persons in news • Awards and honours • Defence news (Joint exercises, Missile tech) • Security forces in INDIA • Space news (ISRO and NASA) • Static Geography (Passes, rivers, ports, grasslands) For Corrections & Feedback • Static Polity (Articles, Landmark Cases, Amendments, FR, DPSP) Email Address [email protected] If this document was helpful in anyway, please give us a feedback and Phone number scope for improvements – Thank you 9545033825 Copyright © by DNYANADEEP ACADEMY, PUNE All rights are reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of DNYANADEEP ACADEMY, PUNE DNYANADEEP IAS SUPER SERIE S – CAP F 2 0 1 9 DNYANADEEP ACADEMY FOR UPSC AND MPSC, PUNE 2 DNYANADEEP IAS SUPER SERIE S – CAP F 2 0 1 9 Table of Contents ANALYSIS ............................................................................................................................................................. 7 CAPF 2018 Topic Wise Questions ....................................................................................................................... -

The Kargil Review Committee Report – 1999

The Kargil Review Committee Report Against the backdrop of an animated public discussion on Pakistan's aggression in Kargil, the Union Government vide its order dated July 29, 1999 constituted a Committee to look into the episode with the following Terms of Reference:- i. to review the events leading up to the Pakistani aggression in the Kargil district of Ladakh in Jammu and Kashmir; and ii. To recommended such measures as are considered necessary to safeguard national security against such armed intrusions. The Committee comprised four members namely K Subrahmanyam (Chairman), Lieutenant General (Retd) K K Hazari, B G Verghese and Satish Chandra, Secretary, National Security Council Secretariat who was also designated as Member-Secretary. Given its open ended terms of reference, the time constraint and, most importantly, the need for clarity in setting about its task, the Committee found it necessary to define its scope of work precisely. To deal with the Kargil episode in isolation would have been too simplistic; hence the Report briefly recounts the important facets of developments in J&K and the evolution of the LOC, Indo-Pak relations since 1947, the proxy war in Kashmir and the nuclear factor. However, the Committee's 'review' commences essentially from 1997 onwards coinciding with Nawaz Sharif's return to office as Prime Minister of Pakistan. This has enabled the Committee to look at developments immediately preceding the intrusions more intensively. The Committee has sought to analyse whether the kind of Pakistani aggression that took place could have been assessed from the available intelligence inputs and if so, what were the shortcomings and failures which led to the nation being caught by surprise.