O-Bahn City Access Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Transport Buildings of Metropolitan Adelaide

AÚ¡ University of Adelaide t4 É .8.'ìt T PUBLIC TRANSPORT BUILDII\GS OF METROPOLTTAN ADELAIDE 1839 - 1990 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Architecture and Planning in candidacy for the degree of Master of Architectural Studies by ANDREW KELT (û, r're ¡-\ ., r ¡ r .\ ¡r , i,,' i \ September 1990 ERRATA p.vl Ljne2}oBSERVATIONshouldreadOBSERVATIONS 8 should read Moxham p. 43 footnote Morham facilities p.75 line 2 should read line 19 should read available Labor p.B0 line 7 I-abour should read p. r28 line 8 Omit it read p.134 Iine 9 PerematorilY should PerernPtorilY should read droP p, 158 line L2 group read woulC p.230 line L wold should PROLOGUE SESQUICENTENARY OF PUBLIC TRANSPORT The one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the establishment of public transport in South Australia occurred in early 1989, during the research for this thesis. The event passed unnoticed amongst the plethora of more noteworthy public occasions. Chapter 2 of this thesis records that a certain Mr. Sp"y, with his daily vanload of passengers and goods, started the first regular service operating between the City and Port Adelaide. The writer accords full credit to this unsung progenitor of the chain of events portrayed in the following pages, whose humble horse drawn char ò bancs set out on its inaugural joumey, in all probability on 28 January L839. lll ACKNO\ryLEDGMENTS I would like to record my grateful thanks to those who have given me assistance in gathering information for this thesis, and also those who have commented on specific items in the text. -

Noarlunga Rail Line to Seaford Final Report

Final Report October 2007 extension of the noarlunga rail line to seaford Final Report This report has been produced by the Policy and Planning Division Department for Transport, Energy and Infrastructure extension of the noarlunga rail line to seaford EXTENSION OF THE NOARLUNGA RAIL LINE TO SEAFORD EXECUTIVE SUMMARY South Australia’s Strategic Plan is a comprehensive Initial work on a possible extension commenced in statement of what South Australia’s future can be. Its the mid 1970s during the time of the construction of targets aim for a growing and sustainable economy the Lonsdale to Noarlunga Centre rail line, with the and a strong social fabric. most direct route for a rail alignment from Noarlunga Some of these targets are ambitious and are beyond to Seaford being defined during the 1980s. Further the reach of government acting alone. Achieving consideration occurred in the late 1980s during the the targets requires a concerted effort not only from initial structure planning for the urban development the State Government, but also from local at Seaford. This resulted in a transport corridor being government, regional groups, businesses and their reserved within this development. associations, unions, community groups and In March 2005 the Government released the individual South Australians. Strategic Infrastructure Plan for South Australia which This vision for SA’s future requires infrastructure initiated an investigation into the extension of the and a transport system which maximise South Noarlunga rail line to Seaford as part of a suite of Australia’s economic efficiency and the quality infrastructure interventions to encourage the shift to of life of its people. -

Download Here

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Source: - TRANSIT AUSTRALIA - February 2004, Vol. 59, No. 2 p41 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ People for Public Transport Conference – October 2003 'Missed Opportunities - New Possibilities' in Adelaide 1. Overview Adelaide's transport action group People for Public Transport held its annual conference 'Missed Opportunities - New Possibilities' on Saturday 25 October 2003 at Balyana Conference Centre, Clapham, attracting some notable speakers and considerable interest. The next three pages present a brief overview of the event and highlights of the speakers' comments. The keynote speaker was Dr Paul Mees, a well known public transport advocate from Melbourne, where he teaches transport and land use planning in the urban planning program at the University of Melbourne. He was President of the Public Transport Users Association (Vic) from 1992 to 2001. (See separate panel page 42.) Dr Alan Perkins talked about the benefits of making railway stations centres for the community, with commercial and medium density housing clustered around the stations and noted places where this had not happened. He stressed the importance of urban design and security at stations. Dr Perkins' work has focused on the nexus of urban planning, transport, greenhouse impacts and sustainability, through research and policy development. He is Senior Transport Policy Analyst with the SA Department of Transport and Urban Planning. See below. Mr Roy Arnold, General Manager of TransAdelaide' talked about his vision for the future of Adelaide's suburban rail, including the new trams, to be introduced in 2005. This is summarised on page 42. Mr Nell Smith, General Manager of Swan Transit (Perth) and a director of Torrens Transit in Adelaide, has been deeply involved in the service reviews that have led to the reversal of long term patronage decline in both cities. -

2017-18 DPTI Annual Report

Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure 2017-18 Annual Report Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure GPO Box 1533 Adelaide SA 5001 https://dpti.sa.gov.au/ Contact phone number 08 7109 7313 Contact email https://www.dpti.sa.gov.au/contact_us ISSN (PRINT VERSION) 2200-5879 ISSN (ONLINE VERSION) 2202-2015 Date presented to Minister: 28 September 2018 2017-18 ANNUAL REPORT for the Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure Contents Contents .................................................................................................................... 3 Section A: Reporting required under the Public Sector Act 2009, the Public Sector Regulations 2010 and the Public Finance and Audit Act 1987 ................. 4 Agency purpose or role ..................................................................................................... 4 Objectives ......................................................................................................................... 4 Key strategies and their relationship to SA Government objectives ................................... 4 Agency programs and initiatives and their effectiveness and efficiency ............................. 6 Legislation administered by the agency ............................................................................. 8 Organisation of the agency .............................................................................................. 10 Employment opportunity programs ................................................................................. -

Signal 161 Passed at Danger Transadelaide Passenger Trainh307

ATSB TRANSPORT SAFETY INVESTIGATION REPORT Rail Occurrence Investigation 2006/003 Final Signal 161 Passed at Danger TransAdelaide Passenger Train H307 Adelaide, South Australia 28 March 2006 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Postal address: PO Box 967, Civic Square ACT 2608 Office location: 15 Mort Street, Canberra City, Australian Capital Territory Telephone: 1800 621 372; from overseas + 61 2 6274 6590 Accident and serious incident notification: 1800 011 034 (24 hours) Facsimile: 02 6274 6474; from overseas + 61 2 6274 6474 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.atsb.gov.au © Commonwealth of Australia 2007. This work is copyright. In the interests of enhancing the value of the information contained in this publication you may copy, download, display, print, reproduce and distribute this material in unaltered form (retaining this notice). However, copyright in the material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you want to use their material you will need to contact them directly. Subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968, you must not make any other use of the material in this publication unless you have the permission of the Australian Transport Safety Bureau. Please direct requests for further information or authorisation to: Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Copyright Law Branch Attorney-General’s Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton ACT 2600 www.ag.gov.au/cca # ISBN and formal report -

Re-Imagining Adelaide's Public Transport by Andrew Leunig 28 August 2013

Re-imagining Adelaide's Public Transport By Andrew Leunig 28 August 2013 With some further notes as at 20 March 2015 (at rear) Re-imagining Adelaide's Public Transport Exec Summary I believe that Adelaide could be the most livable and most learning City on the Planet. The “most liveable” city in the world will get the balance between Public and Private transport right. It will be “liveable” for the old and the young, the rich and the poor. Why couldn't Adelaide have the cleverest, most vibrant public transport system for a town of it's size on the planet ? No Reason at all. But we have to want it first. At the moment our Public Transport mode share (9.9%) is about the lowest in Australia and that is our accepted norm. Even our state plan is soft and timid. “Increase the use of public transport to 10% of metropolitan weekday passenger vehicle kilometres travelled by 2018”. I like the old saying "If you shoot for the stars you might not get there but you are less likely to come up with fists full of mud". At the moment our state plan shoots for the mud. The solution ? We need to reimagine our network design. As recommended by leading experts we should toss out our current hub (city) and spoke design and design our Network around the very layout that Adelaide is globally famous for our grid. I propose that we create The Adelaide Metro Grid with buses running frequently in a straight line along our major roads, where transfers are presumed and every major intersection becomes a transfer point. -

Rftf Final Report.Pdf

Disclaimer The Rail Freight Task Force Report has been prepared with funding and assistance from Mitcham Council. The Report is the result of collaboration between members of the Rail Freight Task Force and various community representatives and aims to provide an alternative perspective on rail freight through the Adelaide area. The information provided in the Report provides a general overview of the issues surrounding rail freight transport in the Mitcham Council (and/or surrounding) area. The Report is not intended as a panacea for current rail transport problems but offers an informed perspective from the Rail Freight Task Force. Findings and recommendations made in the Report are based on the information sourced and considered by the Rail Freight Task Force during the period of review and should not be relied on without independent verification. Readers are encouraged to utilise all relevant sources of information and should make their own specific enquiries and take any necessary action as appropriate before acting on any information contained in this Report. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY....................................................................................................................................3 1. BACKGROUND INFORMATION ............................................................................................................6 Importance of the Railway System.......................................................................................................6 How Much Freight Moves Through the Adelaide Hills -

Final Report Public Transport

PP 282 FINAL REPORT PUBLIC TRANSPORT SIXTY - FIFTH REPORT OF THE ENVIRONMENT, RESOURCES AND DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE Tabled in the House of Assembly and ordered to be published, 1 December 2009 Third Session, Fifty-first Parliament - ii - Committee’s Foreword The Environment, Resources and Development Committee commenced its inquiry into Public Transport on 2 April 2008. As part of the inquiry, 42 submissions were received and 11 witnesses were heard. Submissions and witnesses included key players from state and local government, industry, academics, non-government organisations and community groups, providing a cross-section of views and ideas on Public Transport in South Australia. The Committee extends its thanks for the effort made by those involved in preparing and presenting evidence to the Committee. It provided the Committee members with a better understanding of Public Transport in South Australia, and highlighted some of the key issues facing our state. The Committee thanks the research team; Professor Michael A P Taylor, Professor Derek Scrafton and Dr Nicholas Holyoak, Institute for Sustainable Systems and Technologies, University of South Australia whose work, research and collation of information ensures that the report will be of great value to individuals and organisations concerned with transport in SA. Ms Lyn Breuer, MP Presiding Member 1 December 2009 Parliament of South Australia. Environment, Resources and Development Committee - iii - Committee Summary of Findings In an ideal world public transport would be available, affordable, safe and clean - in the carbon neutral sense. Somehow the domination of the car would not have it placed in catch up mode and being ill prepared to face the challenges raised by climate change and peak oil. -

Our Plan Our Plan

OUR PLAN OUR PLAN TRANSPORT NETWORKS THAT CONNECT PEOPLE TO PLACES AND BUSINESSES TO MARKETS For inner and middle Adelaide • A sharper focus on inner Adelaide to boost the central city as a creative, lively and energetic area where more people want to live and businesses want to locate. • Making bold choices − bringing a network of trams back to Adelaide, called AdeLINK and refocusing our transport system to support and actively encourage mixed-use medium density, vibrant communities and business growth in inner and middle urban areas. For Greater Adelaide • An increasing focus on major urban centres and accessibility to these centres − building upon the electrification of the north-south backbone of the public transport system, a modernised and redesigned bus network with a focus on major activity centres, and supporting a more active city through better connected walking and cycling networks and walkable environments. • Giving businesses the efficient, reliable transport connections they need to deliver goods and services around the city and to interstate and international markets − a well-targeted package of investment in the North-South Corridor, Inner and Outer Ring Routes and intersection and road upgrades. For regional and remote South Australia • Better connecting regional towns and communities to jobs, services and opportunities − focusing on a high quality, well maintained road network and improving community and passenger transport services. • Managing the growing volumes of freight moving around the state and making sure the mining sector has the transport connections it needs to expand. 40 OUR PLAN 3.1 OUR PLAN FOR INNER AND MIDDLE ADELAIDE Liveability is one of Adelaide’s greatest assets. -

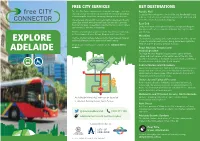

Explore Adelaide

FREE CITY SERVICES KEY DESTINATIONS The free City Connector bus service runs on two loops – an inner Rundle Mall city loop and an extended loop around North Adelaide providing Located in the north-eastern corner of the city, Rundle Mall boasts a link to popular attractions, shopping, dining and destinations. a diverse retail selection of fashion, beauty, lifestyle and food, and The large loop (98A and 98C) connects North Adelaide and the city is the heart of South Australian shopping. seven days a week, while the small loop (99A and 99C) connects East End the inner city areas on weekdays. Together the two loops provide a service every 15 minutes on weekdays. Quirky retail mixes with high-end fashion, vintage and designer boutiques, with cafes, restaurants and pubs, travel agents, bars The Free city tram takes you between the South Terrace tram stop, and cinemas. the Entertainment Centre, Botanic Gardens and Festival Plaza. West End The Free city tram will also take you to the Royal Adelaide Hospital The West End encompasses the north-western part of the city and EXPLORE and medical precinct at the west end of North Terrace. is home to entertainment venues, dining, casual bars, nightclubs, TAFE SA and the University of South Australia. Detailed route information is available on the Adelaide Metro website Royal Adelaide Hospital and ADELAIDE medical precinct The Royal Adelaide Hospital is located at the corner of North Terrace and West Terrace, at the western end of the city. Also located in this precinct is the South Australian Health and Medical 98A 98C Research Institute and Adelaide Dental Hospital. -

Collision Between Suburban Passenger Trains G231 and 215A in Adelaide Yard, South Australia 24 February 2011

ATSB TRANSPORT SAFETY REPORT The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) is an independent The Rail Occurrence Investigation RO-2011-002 Australian Transport Safety Bureau Preliminary (ATSB) is an independent Commonwealth Government statutory Agency. The Bureau is governed by a Commission and is entirely separate from transport regulators, policy Collision between suburban passenger makers and service providers. The ATSB's function is to improve safety and public confidence in the aviation, marine and rail modes of transport trains G231 and 215A in through excellence in: • independent investigation of transport accidents and other safety occurrences Adelaide Yard, South Australia • safety data recording, analysis and research • fostering safety awareness, knowledge and action. 24 February 2011 The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of apportioning blame or to provide a means for determining liability. Figure 1: Leading railcar 3133 of train G231, looking towards Adelaide Station The ATSB performs its functions in accordance with the provisions of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 and, where applicable, relevant international agreements. When the ATSB issues a safety recommendation, the person, organisation or agency must provide a written response within 90 days. That response must indicate whether the person, organisation or agency accepts the recommendation, any reasons for not accepting part or all of the recommendation, and details of any proposed safety action to give effect to the recommendation. © Commonwealth of Australia 2011 In the interests of enhancing the value of the information contained in this publication you may download, print, reproduce and distribute this material acknowledging the Australian Transport Safety Bureau as the source. However, copyright in the material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals number 3 platform at low speed. -

Gawler Brochure

DELIVERING OUR TRANSPORT FUTURE NOW rail revitalisation gawler line Adelaide’s public transport network is receiving a $2.6 billion overhaul to develop a state-of-the-art and sustainable system that offers faster, cleaner and more frequent and efficient travel. The Gawler line Track closure and public revitalisation will transport alternatives upgrade the track The first stage of the track and key stations in upgrade between North Adelaide preparation for new and Mawson Interchange was completed in 2010. Between electric trains on the September 2011 and early 2012 Adelaide transport the next stage between Mawson network in 2013. Interchange and Gawler Central will be upgraded in preparation It includes: for electrification. > upgrading the track The fastest and safest way for > building new stations at Munno these improvements to be made Para and Elizabeth is by closing that part of the line. > upgrading the Gawler and Elizabeth South stations Every effort will be made to > building a new car park at minimise the inconvenience and Smithfield station plans are in place to offer public transport alternatives for train > electrifying the line to run users. cleaner more efficient trains. The department thanks residents and commuters for their patience while these important infrastructure works take place. 2010 2011 track upgrade works The new electric rail needs a new base to support a fast, smooth and reliable journey for tens of thousands of commuters every day. line now station upgrade Key stations along the Gawler line will be upgraded. closure next The Gawler line will be closed between Mawson Interchange and Gawler Central while the track and key stations on the line are upgraded.