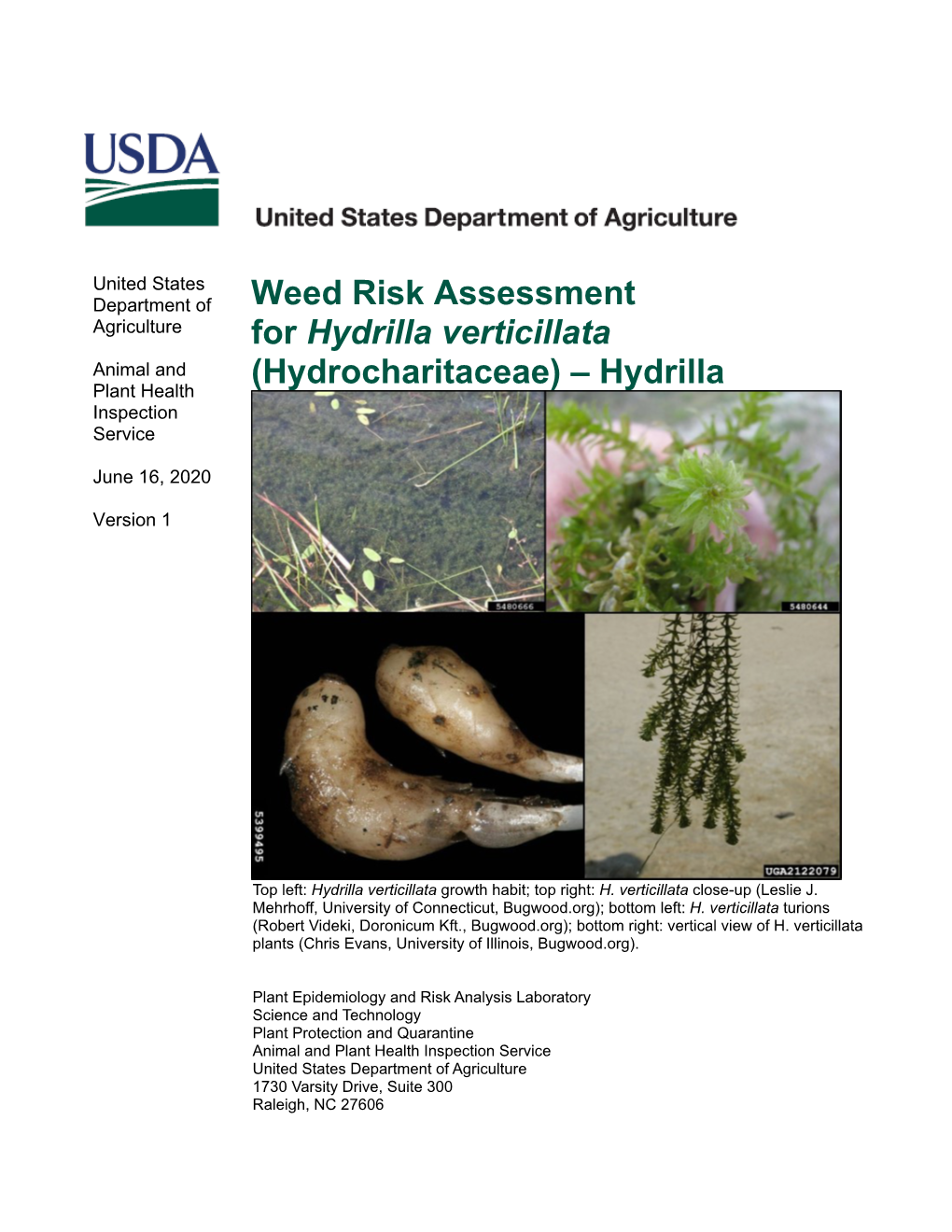

Weed Risk Assessment for Hydrilla Verticillata (Hydrocharitaceae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Red Names=Invasive Species Green Names=Native Species

CURLY-LEAF PONDWEED EURASIAN WATERMIL- FANWORT CHARA (Potamogeton crispus) FOIL (Cabomba caroliniana) (Chara spp.) This undesirable exotic, also known (Myriophyllum spicatum) This submerged exotic Chara is typically found growing in species is not common as Crisp Pondweed, bears a waxy An aggressive plant, this exotic clear, hard water. Lacking true but management tools are cuticle on its upper leaves making milfoil can grow nearly 10 feet stems and leaves, Chara is actually a limited. Very similar to them stiff and somewhat brittle. in length forming dense mats form of algae. It’s stems are hollow aquarium species. Leaves The leaves have been described as at the waters surface. Grow- with leaf-like structures in a whorled are divided into fine resembling lasagna noodles, but ing in muck, sand, or rock, it pattern. It may be found growing branches in a fan-like ap- upon close inspection a row of has become a nuisance plant with tiny, orange fruiting bodies on pearance, opposite struc- “teeth” can be seen to line the mar- in many lakes and ponds by the branches called akinetes. Thick ture, spanning 2 inches. gins. Growing in dense mats near quickly outcompeting native masses of Chara can form in some Floating leaves are small, the water’s surface, it outcompetes species. Identifying features areas. Often confused with Starry diamond shape with a native plants for sun and space very include a pattern of 4 leaves stonewort, Coontail or Milfoils, it emergent white/pinkish early in spring. By midsummer, whorled around a hollow can be identified by a gritty texture flower. -

Hydrilla Vs. New York

1 comicvine.com Hydrilla vs. New York UMISC October 16, 2018 2 Hydrilla in New York High priority species prohibited by Part 575 Now found at 32 locations throughout New York Often found near boat launches DeviantArt Waterfowl also considered a vector 3 Hydrilla in New York First discovered in 2008 2008 - Creamery Pond, Orange County 2008 – Sans Souci Lake, Lotus Lake, Suffolk County 2009 - Lake Ronkonkoma, Blydenburgh/New Mill Pond, Phillips Mill Pond, Suffolk County 2009 – Frost Mill Pond, Suffolk County 2011- Smith Pond, Great Patchoque Lake, Suffolk County; Cayuga Inlet, Tompkins County 2012 – several private ponds, Broome County 2012 – Cayuga Lake, Tompkins County; Tonawanda/Erie Canal, Niagara and Erie Counties 2013 – Croton River, Westchester County 2013 – Millers Pond, Suffolk County; Unnamed pond, Tioga County 2014 – New Croton Reservoir, Westchester County 2014 – Prospect Park, Brooklyn, Kings County 2015 – Tinker Nature Park pond, Monroe County 2016 – Aurora (Cayuga Lake), Tompkins County 2016 – Spencer Pond, Tioga County 2016 – Halsey Neck Road Pond, Suffolk County 2018 - Kuhlman Pond, Tioga County 2018 - Avon Pond, Frank Melville Pond, and East Setauket, Suffolk County 2018 – Allison Pond, Staten Island, Richmond County 4 Management Options in Place 1) No management 2) Benthic mats 3) Triploid Grass Carp 4) Herbicide 5) Combination (IPM) 5 Option: No management Suffolk County: • Lake Ronkonkoma (10 acres of 240 acres) • Sans Souci (southern 5 acres) • Lotus Lake (13 acres) • Blydenburgh/New Mill Pond (110 acres, coverage -

Introduction to Common Native & Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska

Introduction to Common Native & Potential Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska Cover photographs by (top to bottom, left to right): Tara Chestnut/Hannah E. Anderson, Jamie Fenneman, Vanessa Morgan, Dana Visalli, Jamie Fenneman, Lynda K. Moore and Denny Lassuy. Introduction to Common Native & Potential Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska This document is based on An Aquatic Plant Identification Manual for Washington’s Freshwater Plants, which was modified with permission from the Washington State Department of Ecology, by the Center for Lakes and Reservoirs at Portland State University for Alaska Department of Fish and Game US Fish & Wildlife Service - Coastal Program US Fish & Wildlife Service - Aquatic Invasive Species Program December 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ............................................................................ x Introduction Overview ............................................................................. xvi How to Use This Manual .................................................... xvi Categories of Special Interest Imperiled, Rare and Uncommon Aquatic Species ..................... xx Indigenous Peoples Use of Aquatic Plants .............................. xxi Invasive Aquatic Plants Impacts ................................................................................. xxi Vectors ................................................................................. xxii Prevention Tips .................................................... xxii Early Detection and Reporting -

Elodea Genus: Egeria Or Elodea Family: Hydrocharitaceae Order: Hydrocharitales Class: Liliopsida Phylum: Magnoliophyta Kingdom: Plantae

Elodea Genus: Egeria or Elodea Family: Hydrocharitaceae Order: Hydrocharitales Class: Liliopsida Phylum: Magnoliophyta Kingdom: Plantae Conditions for Customer Ownership We hold permits allowing us to transport these organisms. To access permit conditions, click here. Never purchase living specimens without having a disposition strategy in place. The USDA does not require any special permits to ship and/or receive Elodea except in Puerto Rico, where shipment of aquatic plants is prohibited. However, in order to continue to protect our environment, you must house your Elodea in an aquarium. Under no circumstances should you release your Elodea into the wild. Primary Hazard Considerations Always wash your hands thoroughly before and after you handle your Elodea, or anything it has touched. Availability Elodea is available year round. Elodea should arrive with a green color, it should not be yellow or “slimy.” • Elodea canadensis—Usually bright green with three leaves that form whorls around the stem. The whorls compact as they get closer to the tip. Found completely submerged. Is generally a thinner species of Elodea. Has a degree of seasonality May–June. • Egeria densa—Usually bright green with small strap-shaped leaves with fine saw teeth. 3–6 leaves form whorls around the stem and compact as they get closer to the tip. Usually can grow to be a foot or two long. Is thicker and bushier than E. canadensis. Elodea arrives in a sealed plastic bag. Upon arrival, this should be opened and Elodea should be kept moist, or it should be placed in a habitat. For short term storage (1–2 weeks), Elodea should be placed in its bag into the refriger- ator (4 °C). -

Botanischer Garten Der Universität Tübingen

Botanischer Garten der Universität Tübingen 1974 – 2008 2 System FRANZ OBERWINKLER Emeritus für Spezielle Botanik und Mykologie Ehemaliger Direktor des Botanischen Gartens 2016 2016 zur Erinnerung an LEONHART FUCHS (1501-1566), 450. Todesjahr 40 Jahre Alpenpflanzen-Lehrpfad am Iseler, Oberjoch, ab 1976 20 Jahre Förderkreis Botanischer Garten der Universität Tübingen, ab 1996 für alle, die im Garten gearbeitet und nachgedacht haben 2 Inhalt Vorwort ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Baupläne und Funktionen der Blüten ......................................................................................... 9 Hierarchie der Taxa .................................................................................................................. 13 Systeme der Bedecktsamer, Magnoliophytina ......................................................................... 15 Das System von ANTOINE-LAURENT DE JUSSIEU ................................................................. 16 Das System von AUGUST EICHLER ....................................................................................... 17 Das System von ADOLF ENGLER .......................................................................................... 19 Das System von ARMEN TAKHTAJAN ................................................................................... 21 Das System nach molekularen Phylogenien ........................................................................ 22 -

Population Genetic Structure and Phylogeography of Invasive Aquatic Weed, Elodea Canadensis (Hydrocharitaceae) and Comparative Analyses with E

Population genetic structure and phylogeography of invasive aquatic weed, Elodea canadensis (Hydrocharitaceae) and comparative analyses with E. nuttallii Tea Huotari Department of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Agriculture and Forestry University of Helsinki Finland academic dissertation To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Agriculture and Forestry of the University of Helsinki, for public criticism in Auditorium 1041, Biocenter 2 (Viikinkaari 5, Helsinki), on October 5th, 2012, at 12 noon. helsinki 2012 Supervised by: Dr Helena Korpelainen Department of Agricultural Sciences University of Helsinki, Finland Dr Elina Leskinen Department of Environmental Sciences University of Helsinki, Finland Reviewed by: Dr Jouni Aspi Department of Biology University of Oulu, Finland Dr Alain Vanderpoorten Department of Life Sciences University of Liége, Belgium Examined by: Prof. Katri Kärkkäinen The Finnish Forest Research Institute Oulu, Finland Custos: Prof. Teemu Teeri Department of Agricultural Sciences University of Helsinki, Finland © Wiley (Chapter I) © Springer (Chapter II) © Elsevier (Chapter III) © Authors (Chapter IV) © Hanne Huotari (Layout) isbn 978-952-10-8258-0 (paperback) isbn 978-952-10-8259-7 (pdf) Yliopistopaino Helsinki, Finland 2012 Äidille List of original publications this thesis is based on the following publications and a manuscript, which are referred to in the text by their Roman numerals: I Huotari, T., Korpelainen, H. and Kostamo, K. 2010. Development of microsatellite markers for the clonal water weed Elodea canadensis (Hydrocharitaceae) using inter-simple sequence repeat (ISSR) primers. – Molecular Ecology Resources 10: 576–579. II Huotari, T., Korpelainen, H., Leskinen, E. and Kostamo, K. 2011. Population genetics of invasive water weed Elodea canadensis in Finnish waterways. -

Hydrilla Fact Sheet

HHEADINGEADING OFFOFF HHYDRILLAYDRILLA Another invasive species is heading towards the Great Lakes: Hydrilla verticillata onnative species are a great threat to the Great Because it is so invasive and pervasive, hydrilla Lakes region. So far, much focus has been greatly disrupts the ecological balance of all the areas Nplaced on sea lamprey, zebra mussels, alewife, where it grows. Large, dense hydrilla mats inhibit spiny water fleas, ruffe, goby, purple loosestrife and sunlight from penetrating the water and shade out native Eurasian watermilfoil. Soon, another species - Hydrilla plant species that live in the waters below them. Because verticillata – may join this list. hydrilla mats slow the movement of water, sediments Hydrilla is a robust aquatic plant that may survive build up where hydrilla thrives, decreasing the turbidity and thrive in waters of this area. As of December 2005, and creating good breeding grounds for mosquitoes. biologists have found no evidence of hydrilla in Michigan’s shallow Great Economic Impacts Lakes bays, 11,000 inland lakes or Hydrilla has serious economic thousands of miles of streams. effects resulting from the ecological However, the level of concern for impacts. As mentioned before, hydrilla ecological damage and economic harm can slow the movement of water, to Michigan’s water resources has disrupting the water supply, impeding increased due to the fact that hydrilla drainage and irrigation. This adds costs is now known to exist in two Great to the agricultural economy and also Lakes states, Pennsylvania and New negatively affects real estate values that York. are dependent upon attractive nearby waterways. Ecological Impacts Hydrilla also affects recreational Hydrilla has many adaptive qualities activities and the associated economy. -

2014 Hydrilla Integrated Management

Reviewed January 2017 Publishing Information The University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) is an Equal Opportunity Institution. UF/IFAS is committed to diversity of people, thought and opinion, to inclusiveness and to equal opportunity. The use of trade names in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information. UF/IFAS does not guarantee or warranty the products named, and references to them in this publication do not signify our approval to the exclusion of other products of suitable composition. All chemicals should be used in accordance with directions on the manufacturer’s label. Use pesticides and herbicides safely. Read and follow directions on the manufacturer’s label. For questions about using pesticides, please contact your local county Extension office. Visit http://solutionsforyourlife.ufl.edu/map to find an office near you. Copyright 2014, The University of Florida Editors Jennifer L. Gillett-Kaufman (UF/IFAS) Verena-Ulrike Lietze (UF/IFAS) Emma N.I. Weeks (UF/IFAS) Contributing Authors Julie Baniszewski (UF/IFAS) Ted D. Center (USDA/ARS, retired) Byron R. Coon (Argosy University) James P. Cuda (UF/IFAS) Amy L. Giannotti (City of Winter Park) Judy L. Gillmore (UF/IFAS) Michael J. Grodowitz (U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center) Dale H. Habeck, deceased (UF/IFAS) Nathan E. Harms (U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center) Jeffrey E. Hill (UF/IFAS) Verena-Ulrike Lietze (UF/IFAS) Jennifer Russell (UF/IFAS) Emma N.I. Weeks (UF/IFAS) Marissa L. Williams (City of Maitland) External Reviewers Nancy L. Dunn (Florida LAKEWATCH volunteer) Stephen D. -

Hydrilla Verticillata Threatens South African Waters

Hydrilla verticillata threatens South African waters J.A. Coetzee1 and P.T. Madeira2 Summary South Africa’s inland water systems are currently under threat from hydrilla, Hydrilla verticillata L. Royle (Hydrocharitaceae), the worst submerged aquatic weed in the USA. The presence of the weed was confirmed for the first time in South Africa in February 2006, on Pongolapoort Dam in KwaZulu-Natal. An aerial survey revealed that the infestation on this dam covers approximately 600 ha, which is far greater than initially thought. Despite reports that it may be present in other water bodies, surveys have shown that it is restricted to Pongolapoort Dam. We conducted a boater survey which showed that there is significant potential for this devastating weed to spread beyond Pongo- lapoort Dam, and containment of hydrilla is of utmost priority. Research into the suitability of the already established biological control agents, Hydrellia pakistanae Deonier and H. balciunasi Bock (Diptera: Ephydridae), from the USA, as potential agents in South Africa, is also being conducted. However, the South African hydrilla biotype is different from the biotypes in the USA, and this needs to be borne in mind when considering which agents to release. Keywords: potential spread, management, genetic analysis. Introduction Current distribution of The confirmation of Hydrilla verticillata L. Royle hydrilla in South Africa (Hydrocharitaceae) (hydrilla) in South Africa from and potential for spread Pongolapoort Dam, KwaZulu-Natal province (KZN), in early 2006 (L. Henderson, personal communication, Hydrilla is one of the most problematic submerged 2006) prompted immediate action to contain and con- plants worldwide, invading both tropical and temperate trol this weed, and prevent further spread to other wa- regions because of its tolerance to a wide range of envi- ter bodies around South Africa. -

Responses of Aquatic Plant Communities to Stream and Riparian Restoration and Management

Responses of Aquatic Plant Communities to Stream and Riparian Restoration and Management By EMILY PEFFER ZEFFERMAN B.S (Florida State University) 2007 DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Ecology in the OFFICE OF GRADUATE STUDIES of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA DAVIS Approved: ________________________________________________________ Truman P. Young, Chair ________________________________________________________ Eliška Rejmánková ________________________________________________________ Peter B. Moyle Committee in Charge 2014 i UMI Number: 3685316 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3685316 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 Acknowledgements I owe a debt of gratitude to a large number of people without whom this dissertation would not have been possible. The following words cannot express the full magnitude of all the ways in which I have been helped and humbled by my amazing colleagues, friends, and family throughout this journey. Nor can they include every individual who has helped me along the way. With these words, I merely hope to skim the surface of the deep pool of gratitude I feel for the many wonderful people who have been, and will hopefully continue to be, in my life. -

A Key to Common Vermont Aquatic Plant Species

A Key to Common Vermont Aquatic Plant Species Lakes and Ponds Management and Protection Program Table of Contents Page 3 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 How To Use This Guide ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Field Notes .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Plant Key ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 Submersed Plants ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 8-20 Pipewort Eriocaulon aquaticum ...................................................................................................................................................................... 9 Wild Celery Vallisneria americana .................................................................................................................................................................. -

Comparative Efficacy of Diquat for Control of Two Members of The

J. Aquat. Plant Manage. 43: 103-105 Comparative Efficacy of Diquat for Control of Two Members of the Hydrocharitaceae: Elodea and Hydrilla LEE ANN M. GLOMSKI1, JOHN G. SKOGERBOE2, AND KURT D. GETSINGER3 INTRODUCTION in controlling submersed plants in areas influenced by water exchange, this study was designed to evaluate the efficacy of The submersed plants hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata (L.f.) diquat on hydrilla and elodea under various CET scenarios. Royle) and elodea (Elodea canadensis Rich.) are both mem- bers of the Hydrocharitaceae family and cause problems in MATERIALS AND METHODS waterways throughout the world. Hydrilla is a serious nui- sance weed in the southeast, and parts of the mid-Atlantic This experiment was conducted in a greenhouse facility at and western U.S. Although elodea is native to the U.S. in the U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center’s northern and western states, it can grow to nuisance levels in Lewisville Aquatic Ecosystem Research Facility (LAERF) locat- irrigation canals, swimming areas, and boat marinas. Elodea ed in Lewisville, TX in March 2003. Sediment was collected has also invaded many European waterways (Sculthorpe from LAERF ponds, amended with 3 g L-1 ammonium sulfate 1967) and is considered to be an invasive weed in areas of Af- and placed into 1 L plastic pots to serve as plant growth me- rica, Asia, Australia and New Zealand (Bowmer et al. 1995). dia. Three healthy 6-inch apical tips were planted into each α Diquat (6,7-dihydrodipyrido[1,2- :2’,1’-c]pyrazinediium pot. Two pots of each species were placed into 50 L glass dibromide) is a contact herbicide used to control nuisance aquariums, which were filled with alum-treated water supplied submersed and floating aquatic macrophytes.