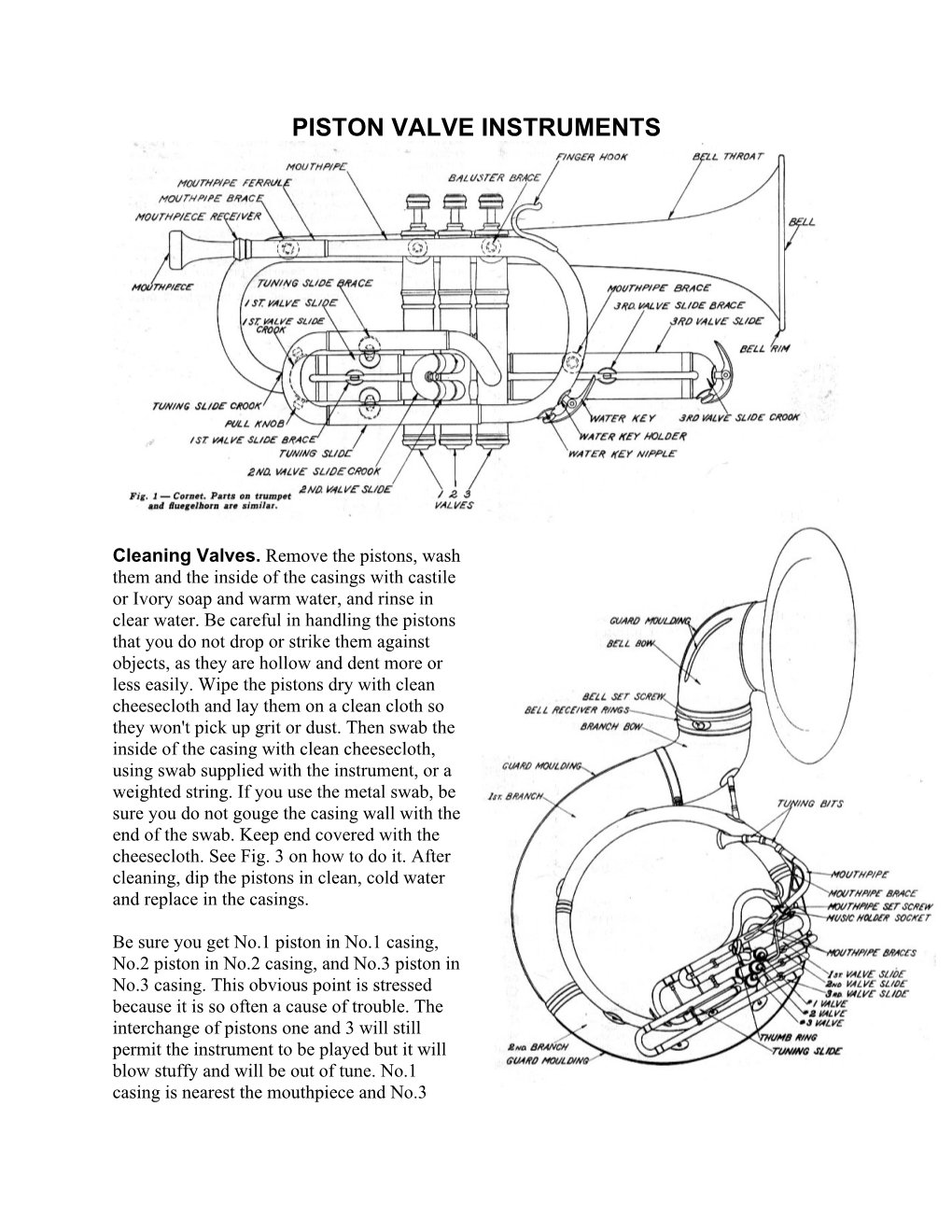

Piston Valve Instruments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE of FINE ARTS Dissertation MERRI FRANQUIN and HIS CONTRIBUTION to the ART of TRUMPET PLAYING by GEOFFRE

BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS Dissertation MERRI FRANQUIN AND HIS CONTRIBUTION TO THE ART OF TRUMPET PLAYING by GEOFFREY SHAMU A.B. cum laude, Harvard College, 1994 M.M., Boston University, 2004 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts 2009 © Copyright by GEOFFREY SHAMU 2009 Approved by First Reader Thomas Peattie, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Music Second Reader David Kopp, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Music Third Reader Terry Everson, M.M. Associate Professor of Music To the memory of Pierre Thibaud and Roger Voisin iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Completion of this work would not have been possible without the support of my family and friends—particularly Laura; my parents; Margaret and Caroline; Howard and Ann; Jonathan and Françoise; Aaron, Catherine, and Caroline; Renaud; les Davids; Carine, Leeanna, John, Tyler, and Sara. I would also like to thank my Readers—Professor Peattie for his invaluable direction, patience, and close reading of the manuscript; Professor Kopp, especially for his advice to consider the method book and its organization carefully; and Professor Everson for his teaching, support and advocacy over the years, and encouraging me to write this dissertation. Finally, I would like to acknowledge the generosity of the Voisin family, who granted interviews, access to the documents of René Voisin, and the use of Roger Voisin’s antique Franquin-system C/D trumpet; Veronique Lavedan and Enoch & Compagnie; and Mme. Courtois, who opened her archive of Franquin family documents to me. v MERRI FRANQUIN AND HIS CONTRIBUTION TO THE ART OF TRUMPET PLAYING (Order No. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75 Conference or Workshop Item How to cite: Smith, David and Blundel, Richard (2016). Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75. In: Association of Business Historians (ABH) and Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG) Joint Conference, 27-29 May 2016, Humbolt University, Berlin. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2016 The Authors https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://ebha.org/public/C6:pdf Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Joint Conference Association of Business Historians (ABH) and Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG), 27-28 May 2016, Humboldt University Berlin, Germany Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75 David Smith* and Richard Blundel** *Nottingham Trent University, UK and **The Open University, UK Abstract This paper examines the interplay between innovation and entrepreneurial processes amongst competing firms in the creative industries. It does so through a case study of the introduction and diffusion into Britain of a brass musical instrument, the wide bore German horn, over a period of some 40 years in the middle of the twentieth century. -

Care & Maintenance

Care and Maintenance of the Euphonium and Piston-Valve Tuba You Will Need: 1) Soft cloth (cotton or flannel) 4) Valve brush 2) Flexible brush (also called a “snake”) 5) Tuning slide grease 3) Mouthpiece brush 6) Valve Oil Daily Care 1) Never leave your instrument unattended. It takes very little time for someone to take it. 2) The safest place for your instrument is in the case. Leave it there when you’re not playing. 3) Do not let other people use your instrument. They may not know how to hold and care for it. 4) Do not use your case as a chair, foot rest or step stool. It is not designed for that kind of weight. 5) Lay your case flat on the floor before opening it. Do not let it fall open. 6) Do not hit your mouthpiece, it can get stuck. 7) Do not lift your instrument by the valves. Use the bell and any large tubes on the outside edge. 8) No loose items in your case. Anything loose will damage your instrument or get stuck in it. 9) Do not put music in your case, unless space is provided for it. If you have to fold it or if it touches the instrument, it should NOT be there. 10) Avoid eating or drinking just before playing. If you do, rinse your mouth with water before playing. 11) You may not need to do it every day, but keep your valves running smooth with valve oil. Put the oil directly on the exposed valve, not in the holes on the bottom of the casings. -

Price List Valid From: 01.01.2020

Mosenstr. 10 - 08258 Markneukirchen - Tel. 037422 2871 / Fax -749631 www.schmidt-brass.de - E-Mail: [email protected] price list valid from: 01.01.2020 mo./ no. description price in €, price in €, excl. of incl. of 19% VAT VAT hunting instruments 19/01 pocket hunting-horn, brass model 351,72 418,52 19/021 c-signalhorn, brass model, single coil, with case 651,92 775,73 19/022 c-signalhorn, brass model, double coil, with case 674,33 802,39 19/02 prince pless horn, brass model, with case 716,91 853,06 19/03 prince pless horn with rotary valve mechanism, with case 1544,71 1838,07 19/04 parforce horn, brass model, with case 1438,29 1711,44 19/05 parforce horn, brass model with switching valve, with case 1756,34 2089,89 signal instruments 19/08 natural trumpet in b-es flat with switching valve, gig bag 1062,17 1263,89 german trumpets – concert trumpets with rotary valves 20/01 cornet in b, brass model/golden brass, with case or gig bag 1965,35 2338,56 20/01 S same model such as 20/01, silver plated 2236,53 2661,27 20/05 c-trumpet, brass model/golden brass model, case/gig-bag 2159,04 2569,06 20/05 S same model such as 20/051, silver plated 2696,07 3208,08 20/07 b-trumpet, “Cologne model”, brass model/golden brass model, case 1923,88 2289,24 20/07 S same model such as 20/07, silver plated 2202,29 2620,53 20/08 b-trumpet, „Cologne model”, golden brass model, bell joint with small 2429,81 2891,25 nickel silver wreath, trigger on third valve, case 20/08 S same model such as 20/08, silver plated 2707,95 3222,21 20/09 b-trumpet „Heckel model“, brass model/golden brass model, 2501,22 2976,22 trigger on third valve, case 20/09 S same model such as 20/09, silver plated 2779,73 3307,63 optional J. -

The Evolution of the Bugle

2 r e The evolution t p a h C of the bugle by Scooter Pirtle L Introduction activity ponders how it will adapt itself to the ceremonies, magical rites, circumcisions, When one thinks of the evolution of the future, it may prove beneficial to review the burials and sunset ceremonies -- to ensure bugle used by drum and bugle corps, a manner by which similar ensembles that the disappearing sun would return. timeline beginning in the early 20th Century addressed their futures over a century ago. Women were sometimes excluded from might come to mind. any contact with the instrument. In some While the American competitive drum and A very brief history of the Amazon tribes, any woman who even glanced bugle corps activity technically began with trumpet and bugle at a trumpet was killed. 2 Trumpets such as the American Legion following the First through the 18th Century these can still be found in the primitive World War (1914-1918), many innovations cultures of New Guinea and northwest Brazil, had already occurred that would guide the L Ancient rituals as well as in the form of the Australian evolution of the bugle to the present day and Early trumpets bear little resemblance to didjeridu.” 3 beyond. trumpets and bugles used today. They were Throughout ancient civilization, the color Presented in this chapter is a narrative on straight instruments with no mouthpiece and red was associated with early trumpets. This important events in the evolution of the no flaring bell. Used as megaphones instead could probably be explained by the presence bugle. -

The Brass Instrument Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

113 THE BRASS INSTRUMENT COLLECTION OF THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART IN NEW YORK HERBERT HEYDE The Metropolitan Museum of Art houses a large, comprehensive collection of musical instruments. Managed by one of seventeen curatorial departments, the Musical Instruments Department, it contains approximately 4,500 instruments. Roughly forty percent of them are of western, the rest of non-western origin. The Egyptian, Islamic, Arms and Armor, Medieval Departments, and a few other departments, house some additional instruments. Another resource consists of iconographic representations of musical instruments that are to be found in almost all departments. They are included in The Performing Arts Index of RIdIM.1 The western brass, or “lip-vibrated” instruments of the Musical Instruments Department amount to only 283 items—an indication that this fi eld was never a priority of the museum’s collecting activities. The basis of The Metropolitan Museum of Art musical instruments collection was provided by Mary Elisabeth Adams Brown (1842-1918), who donated her collection from 1889 in successive installments in the name of her husband, John Crosby Brown. Beginning with 276 instruments in 1889, the gift ultimately amounted to more than 3400 items in 1918. To be precise, before Brown’s donation there was already a collection of forty-four instruments in the museum, given by Joseph William Drexel (1833-1888), a wealthy amateur musician and philanthropist in New York. The Brown family, of British origin, engaged in international banking and graciously supported American culture, including education and theology. Besides musical instruments, Mrs. Brown collected lace, embroidery, and portraits of musicians, which are now kept in the Prints and Drawings Department of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.2 A few years after the Crosby Brown collection began to arrive in 1889, the museum provided gallery space for its public display. -

The Political, Economic, and Social Reasons Behind the Saxophone's Exclusion from the Symphony Orchestra

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Honors Projects Overview Honors Projects 2017 More Than Its Sound: The olitP ical, Economic, and Social Reasons Behind the Saxophone's Exclusion from the Symphony Orchestra Kyle Beaudoin Rhode Island College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects Part of the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Beaudoin, Kyle, "More Than Its Sound: The oP litical, Economic, and Social Reasons Behind the Saxophone's Exclusion from the Symphony Orchestra" (2017). Honors Projects Overview. 131. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects/131 This Honors is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Projects at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects Overview by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MORE THAN ITS SOUND: THE POLITICAL, ECONOMIC, AND SOCIAL REASONS BEHIND THE SAXOPHONE'S EXCLUSION FROM THE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Kyle Beaudoin An Honors Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment for Honors in The Department of Music, Theatre, and Dance The School of Arts and Sciences Rhode Island College 2017 i ABSTRACT The purpose of this project is to uncover the reasons why the saxophone was not integrated into the orchestra. Through an examination of political, economic, and cultural accounts of Paris during the nineteenth century, this paper attempts to examine the effects on the saxophone’s reception. During the nineteenth century, French composers had a vehement fascination with timbre and the manipulation of its effects as a new aesthetic dimension in music; the perfect environment for an entirely new timbre to be added to ensembles, let alone introduced. -

Rhetoric Level - Music

Catholic Schoolhouse Year 3 - Rhetoric Level - Music Quarter 4 – Brass Instruments Class Opener: Brainstorm all the places and genres that you recall in which brass instruments commonly perform. Which are your favorites? Can you easily tell when you are hearing a brass instrument versus another kind of instrument? How can you tell? Brass Instruments The brass family of instruments are wind instruments usually made of brass or other metal through which a sound is produced by buzzing the lips into a mouthpiece and using the lips, chin and tongue to alter the pitch. Brass instruments are aerophones, or wind instruments, and though they may appear fairly complicated, they are really just a long metal tube through which air travels. These metal tubes are typically bent into S-curves or loops to make them more compact and easy to handle, but if they were each to be stretched to their maximum length, it would be evident that the shorter instruments produce higher sounds than the longer ones. That is because the column of air in the instrument, like the length of the string on a violin or cello, is what vibrates and determines the pitch. The pitch of a brass instrument can be altered by using the lips alone to reach the octaves, fifths and fourths, but the remaining notes are produced by means of valves, which redirect the air through the metal tube in various directions, or slides, which lengthen the metal tube to various degrees. Brass mouthpiece image credit Basic brass instruments include the trumpet, French horn, trombone, and tuba. -

The “Catholic” Fingering—First Valve Semitone: Reversed Valve Order in Brass Instruments and Related Valve Constructions

73 The “Catholic” Fingering—First Valve Semitone: Reversed Valve Order in Brass Instruments and Related Valve Constructions Joe R. Utley† and Sabine K. Klaus In 1985 Joe R. and Joella F. Utley acquired a trumpet for their collection of brass instruments in which the first and the second valves are reversed (Figure 1a, b); that is, the first valve creates a descending semitone while the second valve lowers the pitch a whole tone. This is the opposite of customary practice today. This trumpet is faintly stamped on its German-silver garland, ALOIS GENTNER IN DIL[LINGEN] (Figure 2). Dillingen is located in south Germany, just north of Augsburg. Figure 1a, b Trumpet in B by Alois Gentner, Dillingen, ca. 1860 (Utley/NMM,f 6821. Photo: Mark Olencki). 74 HISTORIC BRASS SOCIETY JOURNAL Figure 2 Signature of the trumpet by Gentner (Utley/NMM, 6821. Photo: Mark Olencki). For many years it was a curiosity. If handed to accomplished players to blow a few notes, it would befuddle them. A few could figure it out in a few minutes but none had ever heard of this bizarre valve order before. Over the years, several more instruments with this valve order were acquired for the Utley Collection: a trumpet by Andreas Barth, Munich, with only two valves in this configuration (Figure 3a, b); another three-valve trumpet by Dominicus Leicher, Augsburg (Figure 4a, b); a soprano saxhorn by Isaac Fiske, Worcester, Massachusettes (Figure 5); an unsigned American cornet in which the player has the choice between the normal or the reversed valve order (Figure 6a, b); and finally a late-nineteenth-century trumpet by Conrad Weidlich, Regensburg (Figure 7a, b). -

103 Rotary-Valve Trumpets. Instruments with Clock-Spring Returns Constitute

UTLEY & KLAUS 103 Figure 22 Trumpet in C by Andreas Barth, Munich, ca. 1845 (M Stadtmuseum, 79-38); with piston ends after Leopold Uhlmann. rotary-valve trumpets. Instruments with clock-spring returns constitute the second largest group among the double-piston valves, reaching their peak in the 1840s. There is a third operating mechanism for double-piston valves—one which also uses levers, but shorter ones. Such instruments appeared as early as the 1820s, but were used principally in the 1840s and 1850s. These instruments are held vertically with the loop above the bell, like those with long levers. According to Heyde this model originated in Adorf in Saxony, where it is first recorded in a trumpet by Johann Gottlieb Roth. His pupil Carl August Müller (1804-70), who was born in Adorf, built instruments in the same style Figure 23 Unsigned trumpet in G with short levers and flat spring (GNM, MI 380). 104 HISTORIC BRASS SOCIETY JOURNAL around 1835. According to drawings of Müller’s instruments, published by Heyde,24 they had the semitone valve first. Müller settled in Mainz in 1824; this is the reason why this model was called the “Old Mainz” valve later on. The earliest instrument with this construction seems to be the unsigned trumpet in G (GNM, MI 380, Figure 23), which could be as early as 1835 or even a little earlier. This instrument has a flat spring as return mechanism, the oldest form of this valve type. Carl August Müller introduced small rollers to improve the operation of the return- spring in 1835. -

The Modern Tuba: the Evolution of the Instrument, Key Compositions and Extended Techniques

The Modern Tuba: The Evolution of the Instrument, Key Compositions and Extended Techniques Nimrod Haim Ron 1 Listaháskóli Íslands Tónlistardeild Hljóðfæraleikur The Modern Tuba: The Evolution of the Instrument, Key Compositions and Extended Techniques Nimrod Haim Ron Leiðbeinandi: Áskell Másson 2014 2 Abstract The primary goal of this paper is to study the use of the tuba in contemporary music through the history of its repertoire, the evolution of the instrument, and to explore the extended techniques specific to the tuba. In the process of choosing a piece to perform one should ask them how, why, and when it was written. This paper will focus on the historical evolution of the tuba from the Serpent to the Ophicleide concluding with the transition from to the bass tuba. 3 Table of contents The History of the Tuba: Predecessors ....................................................................................... 5 Serpent ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Ophicleide ................................................................................................................................... 7 Bass Tuba .................................................................................................................................... 8 Wagner Tuba ............................................................................................................................. 10 Composers who wrote for the Tuba ......................................................................................... -

The Horn in Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 5, Op. 64: an Introduction to the Horn in Late Nineteenth Century Russia

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work 5-2019 The Horn in Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 5, Op. 64: An Introduction to the Horn in Late Nineteenth Century Russia David S. Hall University Tennessee-Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Part of the Musicology Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Hall, David S., "The Horn in Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 5, Op. 64: An Introduction to the Horn in Late Nineteenth Century Russia" (2019). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/2269 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HORN IN TCHAIKOVSKY’S SYMPHONY NO. 5, OP 64: AN INTRODUCTION TO THE HORN IN LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY RUSSIA David Seth Hall Honors Thesis University of Tennessee, Knoxville May 2, 2019 2 Introduction Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 5, Op. 64 lives on today as one of his more popular works. For horn players, any mention of the symphony immediately conjurs up thoughts of the famous horn solo in second movement. The symphony is filled with colorful writing for the horns that reflects both trends in Tchaikovsky’s approach to writing for horn and horn playing in general in the late 19th century.