An Argument in Favor of the Saxhorn Basse (French Tuba)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE of FINE ARTS Dissertation MERRI FRANQUIN and HIS CONTRIBUTION to the ART of TRUMPET PLAYING by GEOFFRE

BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS Dissertation MERRI FRANQUIN AND HIS CONTRIBUTION TO THE ART OF TRUMPET PLAYING by GEOFFREY SHAMU A.B. cum laude, Harvard College, 1994 M.M., Boston University, 2004 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts 2009 © Copyright by GEOFFREY SHAMU 2009 Approved by First Reader Thomas Peattie, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Music Second Reader David Kopp, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Music Third Reader Terry Everson, M.M. Associate Professor of Music To the memory of Pierre Thibaud and Roger Voisin iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Completion of this work would not have been possible without the support of my family and friends—particularly Laura; my parents; Margaret and Caroline; Howard and Ann; Jonathan and Françoise; Aaron, Catherine, and Caroline; Renaud; les Davids; Carine, Leeanna, John, Tyler, and Sara. I would also like to thank my Readers—Professor Peattie for his invaluable direction, patience, and close reading of the manuscript; Professor Kopp, especially for his advice to consider the method book and its organization carefully; and Professor Everson for his teaching, support and advocacy over the years, and encouraging me to write this dissertation. Finally, I would like to acknowledge the generosity of the Voisin family, who granted interviews, access to the documents of René Voisin, and the use of Roger Voisin’s antique Franquin-system C/D trumpet; Veronique Lavedan and Enoch & Compagnie; and Mme. Courtois, who opened her archive of Franquin family documents to me. v MERRI FRANQUIN AND HIS CONTRIBUTION TO THE ART OF TRUMPET PLAYING (Order No. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75 Conference or Workshop Item How to cite: Smith, David and Blundel, Richard (2016). Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75. In: Association of Business Historians (ABH) and Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG) Joint Conference, 27-29 May 2016, Humbolt University, Berlin. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2016 The Authors https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://ebha.org/public/C6:pdf Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Joint Conference Association of Business Historians (ABH) and Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG), 27-28 May 2016, Humboldt University Berlin, Germany Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75 David Smith* and Richard Blundel** *Nottingham Trent University, UK and **The Open University, UK Abstract This paper examines the interplay between innovation and entrepreneurial processes amongst competing firms in the creative industries. It does so through a case study of the introduction and diffusion into Britain of a brass musical instrument, the wide bore German horn, over a period of some 40 years in the middle of the twentieth century. -

Care & Maintenance

Care and Maintenance of the Euphonium and Piston-Valve Tuba You Will Need: 1) Soft cloth (cotton or flannel) 4) Valve brush 2) Flexible brush (also called a “snake”) 5) Tuning slide grease 3) Mouthpiece brush 6) Valve Oil Daily Care 1) Never leave your instrument unattended. It takes very little time for someone to take it. 2) The safest place for your instrument is in the case. Leave it there when you’re not playing. 3) Do not let other people use your instrument. They may not know how to hold and care for it. 4) Do not use your case as a chair, foot rest or step stool. It is not designed for that kind of weight. 5) Lay your case flat on the floor before opening it. Do not let it fall open. 6) Do not hit your mouthpiece, it can get stuck. 7) Do not lift your instrument by the valves. Use the bell and any large tubes on the outside edge. 8) No loose items in your case. Anything loose will damage your instrument or get stuck in it. 9) Do not put music in your case, unless space is provided for it. If you have to fold it or if it touches the instrument, it should NOT be there. 10) Avoid eating or drinking just before playing. If you do, rinse your mouth with water before playing. 11) You may not need to do it every day, but keep your valves running smooth with valve oil. Put the oil directly on the exposed valve, not in the holes on the bottom of the casings. -

Mcallister Interview Transcription

Interview with Timothy McAllister: Gershwin, Adams, and the Orchestral Saxophone with Lisa Keeney Extended Interview In September 2016, the University of Michigan’s University Symphony Orchestra (USO) performed a concert program with the works of two major American composers: John Adams and George Gershwin. The USO premiered both the new edition of Concerto in F and the Unabridged Edition of An American in Paris created by the UM Gershwin Initiative. This program also featured Adams’ The Chairman Dances and his Saxophone Concerto with soloist Timothy McAllister, for whom the concerto was written. This interview took place in August 2016 as a promotion for the concert and was published on the Gershwin Initiative’s YouTube channel with the help of Novus New Music, Inc. The following is a full transcription of the extended interview, now available on the Gershwin channel on YouTube. Dr. Timothy McAllister is the professor of saxophone at the University of Michigan. In addition to being the featured soloist of John Adams’ Saxophone Concerto, he has been a frequent guest with ensembles such as the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Lisa Keeney is a saxophonist and researcher; an alumna of the University of Michigan, she works as an editing assistant for the UM Gershwin Initiative and also independently researches Gershwin’s relationship with the saxophone. ORCHESTRAL SAXOPHONE LK: Let’s begin with a general question: what is the orchestral saxophone, and why is it considered an anomaly or specialty instrument in orchestral music? TM: It’s such a complicated past that we have with the saxophone. -

A Symphonic Poem on Dante's Inferno and a Study on Karlheinz Stockhausen and His Effect on the Trumpet

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 A Symphonic Poem on Dante's Inferno and a study on Karlheinz Stockhausen and his effect on the trumpet Michael Joseph Berthelot Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Berthelot, Michael Joseph, "A Symphonic Poem on Dante's Inferno and a study on Karlheinz Stockhausen and his effect on the trumpet" (2008). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3187. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3187 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A SYMPHONIC POEM ON DANTE’S INFERNO AND A STUDY ON KARLHEINZ STOCKHAUSEN AND HIS EFFECT ON THE TRUMPET A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agriculture and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Music by Michael J Berthelot B.M., Louisiana State University, 2000 M.M., Louisiana State University, 2006 December 2008 Jackie ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dinos Constantinides most of all, because it was his constant support that made this dissertation possible. His patience in guiding me through this entire process was remarkable. It was Dr. Constantinides that taught great things to me about composition, music, and life. -

The Composer's Guide to the Tuba

THE COMPOSER’S GUIDE TO THE TUBA: CREATING A NEW RESOURCE ON THE CAPABILITIES OF THE TUBA FAMILY Aaron Michael Hynds A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS August 2019 Committee: David Saltzman, Advisor Marco Nardone Graduate Faculty Representative Mikel Kuehn Andrew Pelletier © 2019 Aaron Michael Hynds All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT David Saltzman, Advisor The solo repertoire of the tuba and euphonium has grown exponentially since the middle of the 20th century, due in large part to the pioneering work of several artist-performers on those instruments. These performers sought out and collaborated directly with composers, helping to produce works that sensibly and musically used the tuba and euphonium. However, not every composer who wishes to write for the tuba and euphonium has access to world-class tubists and euphonists, and the body of available literature concerning the capabilities of the tuba family is both small in number and lacking in comprehensiveness. This document seeks to remedy this situation by producing a comprehensive and accessible guide on the capabilities of the tuba family. An analysis of the currently-available materials concerning the tuba family will give direction on the structure and content of this new guide, as will the dissemination of a survey to the North American composition community. The end result, the Composer’s Guide to the Tuba, is a practical, accessible, and composer-centric guide to the modern capabilities of the tuba family of instruments. iv To Sara and Dad, who both kept me going with their never-ending love. -

Das Saxhorn Adolphe Sax’ Blechblasinstrumente Im Kontext Ihrer Zeit

Eugenia Mitroulia/Arnold Myers The Saxhorn Families Introduction The saxhorns, widely used from the middle of the nineteenth century onwards, did not have the same tidy, well-ordered development in Adolphe Sax’s mind and manufacture as the saxophone family appears to have had.1 For a period Sax envisag- ed two families of valved brasswind, the saxhorns and saxotrombas, with wider and narrower proportions respectively. Sax’s production of both instruments included a bell-front wrap and a bell-up wrap. In military use, these were intended for the infantry and the cavalry respectively. Sax’s patent of 1845 made claims for both families and both wraps,2 but introduced an element of confusion by using the term “saxotromba” for the bell-up wrap as well as for the instruments with a narrower bore profile. The confusion in nomenclature continued for a long time, and was exacerbated when Sax (followed by other makers) used the term “saxhorn” for the tenor and baritone members of the nar- rower-bore family in either wrap. The question of the identity of the saxotromba as a family has been answered by one of the present authors,3 who has also addressed the early history of the saxhorns.4 The present article examines the identity of the saxhorns (as they are known today) in greater detail, drawing on a larger sample of extant instruments. In particular, the consistency of Sax’s own production of saxhorns is discussed, as is the question of how close to Sax’s own instruments were those made by other makers. -

The Early Evolution of the Saxophone Mouthpiece 263

THE EARLY EVOLUTION OF THE SAXOPHONE MOUTHPIECE 263 The Early Evolution of the Saxophone Mouthpiece The Early Saxophone Mouthpiece TIMOTHY R. ROSE The early saxophone mouthpiece design, predominating during half of the instrument’s entire history, represents an important component of the or nine decades after the saxophone’s invention in the 1840s, clas- saxophone’s initial period of development. To be sure, any attempt to re- Fsical saxophone players throughout the world sought to maintain a construct the early history of the mouthpiece must be constrained by gaps soft, rounded timbre—a relatively subdued quality praised in more recent in evidence, particularly the scarcity of the oldest mouthpieces, from the years by the eminent classical saxophonist Sigurd Rascher (1930–1977) nineteenth century. Although more than 300 original Adolphe Sax saxo- as a “smooth, velvety, rich tone.”1 Although that distinct but subtle tone phones are thought to survive today,2 fewer than twenty original mouth- color was a far cry from the louder, more penetrating sound later adopted pieces are known.3 Despite this gap in the historical record, this study is by most contemporary saxophonists, Rascher’s wish was to preserve the intended to document the early evolution of the saxophone mouthpiece original sound of the instrument as intended by the instrument’s creator, through scientific analysis of existing vintage mouthpieces, together with Antoine-Joseph “Adolphe” Sax. And that velvety sound, the hallmark of a review of patents and promotional materials from the late nineteenth the original instrument, was attributed by musicians, including Rascher, and early twentieth centuries. -

DOI: 156 Reimar Walthert

Reimar Walthert The First Twenty Years of Saxhorn Tutors Subsequent to Adophe Sax’s relocation to Paris in 1842 and his two saxhorn/saxotromba patents of 1843 and 1845, numerous saxhorn tutors were published by different authors. After the contest on the Champ-de-Mars on 22 April 1845 and the decree by the Ministre de la guerre in August 1845 that established the use of saxhorns in French military bands, there was an immediate need for tutors for this new instrument. The Bibliothèque nationaledeFranceownsaround35tutorspublishedbetween1845and1865forthisfamily of instruments. The present article offers a short overview of these early saxhorn tutors and will analyse both their contents and their underlying pedagogical concepts. Early saxhorn tutors in the Bibliothèque nationale de France The whole catalogue of the French national library can now be found online at the library’s website bnf.fr. It has two separate indices that are of relevance for research into saxhorn tutors. Those intended specifically for the saxhorn can be found under the index number “Vm8-o”, whereas cornet tutors are listed under “Vm8-l”. But the second index should not be ignored with regard to saxhorn tutors, because tutors intended for either cornet or saxhorn are listed only here. The most famous publication in thiscategoryisJean-BaptisteArban’sGrande méthode complète de cornet à pistons et de saxhorn. Meanwhile many of these tutors have been digitised and made accessible on the website gallica.fr. Publication periods It is difficult to date the saxhorn tutors in question. On one hand thereisthestampoftheBibliothèquenationaledeFrance,whichcannotalwaysberelied upon. On the other hand, it is possible to date some publications by means of the plate number engraved by the editor. -

Characterization And' Taxonomy Acoustical Standpoint

Characterization and' Taxonomy of Historic Brass Musical Instruments from ae Acoustical Standpoint Arnold Myers Ph.D. The University of Edinburgh 1998 I" V *\- Abstract The conceptual bases of existing classification schemes for brasswind are examined. The requirements of a taxonomy relating to the character of brass musical instruments as experienced by players and listeners are discussed. Various directly and indirectly measurable physical parameters are defined. The utility of these parameters in classification is assessed in a number of case studies on instruments in museums and collections. The evolution of instrument design since 1750 in terms of these characterization criteria is outlined. Declaration I declare that this thesis has been composed by me and that the work is my own. ? r % *} Acknowledgements I have been encouraged and helped by many in my investigations. My supervisors, D. Murray Campbell in the Department of Physics and Astronomy Christopher D.S. Field, and John Kitchen in the Faculty of Music have provided wise guidance whenever needed. Raymond Parks, Research Fellow in Fluid Dynamics, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Edinburgh, has given unfailing support, and has been responsible for much of the measuring equipment I have used. David Sharp has used the pulse reflectornetry techniques developed in the course of his own research to obtain bore reconstructions of numerous specimens for me. Herbert Heyde kindly discussed the measurement of historic brass instruments with me. Stewart Benzie has carried out instrument repairs for me and made the crook described in Chapter 5. I am grateful to the curators of many museums for allowing me access to the historic instruments in their care. -

The Missing Saxophone Recovered(Updated)

THE MISSING SAXOPHONE: Why the Saxophone Is Not a Permanent Member of the Orchestra by Mathew C. Ferraro Submitted to The Dana School of Music in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music in History and Literature YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY May 2012 The Missing Saxophone Mathew C. Ferraro I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: ____________________________________________________________ Mathew C. Ferraro, Student Date Approvals: ____________________________________________________________ Ewelina Boczkowska, Thesis Advisor Date ____________________________________________________________ Kent Engelhardt, Committee Member Date ____________________________________________________________ Stephen L. Gage, Committee Member Date ____________________________________________________________ Randall Goldberg, Committee Member Date ____________________________________________________________ James C. Umble, Committee Member Date ____________________________________________________________ Peter J. Kasvinsky, Dean of School of Graduate Studies Date Abstract From the time Adolphe Sax took out his first patent in 1846, the saxophone has found its way into nearly every style of music with one notable exception: the orchestra. Composers of serious orchestral music have not only disregarded the saxophone but have actually developed an aversion to the instrument, despite the fact that it was created at a time when the orchestra was expanding at its most rapid pace. This thesis is intended to identify historical reasons why the saxophone never became a permanent member of the orchestra or acquired a reputation as a serious classical instrument in the twentieth century. iii Dedicated to Isabella, Olivia & Sophia And to my father Michael C. -

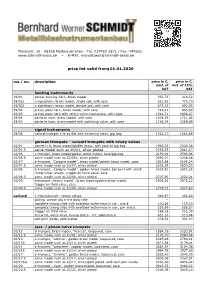

Price List Valid From: 01.01.2020

Mosenstr. 10 - 08258 Markneukirchen - Tel. 037422 2871 / Fax -749631 www.schmidt-brass.de - E-Mail: [email protected] price list valid from: 01.01.2020 mo./ no. description price in €, price in €, excl. of incl. of 19% VAT VAT hunting instruments 19/01 pocket hunting-horn, brass model 351,72 418,52 19/021 c-signalhorn, brass model, single coil, with case 651,92 775,73 19/022 c-signalhorn, brass model, double coil, with case 674,33 802,39 19/02 prince pless horn, brass model, with case 716,91 853,06 19/03 prince pless horn with rotary valve mechanism, with case 1544,71 1838,07 19/04 parforce horn, brass model, with case 1438,29 1711,44 19/05 parforce horn, brass model with switching valve, with case 1756,34 2089,89 signal instruments 19/08 natural trumpet in b-es flat with switching valve, gig bag 1062,17 1263,89 german trumpets – concert trumpets with rotary valves 20/01 cornet in b, brass model/golden brass, with case or gig bag 1965,35 2338,56 20/01 S same model such as 20/01, silver plated 2236,53 2661,27 20/05 c-trumpet, brass model/golden brass model, case/gig-bag 2159,04 2569,06 20/05 S same model such as 20/051, silver plated 2696,07 3208,08 20/07 b-trumpet, “Cologne model”, brass model/golden brass model, case 1923,88 2289,24 20/07 S same model such as 20/07, silver plated 2202,29 2620,53 20/08 b-trumpet, „Cologne model”, golden brass model, bell joint with small 2429,81 2891,25 nickel silver wreath, trigger on third valve, case 20/08 S same model such as 20/08, silver plated 2707,95 3222,21 20/09 b-trumpet „Heckel model“, brass model/golden brass model, 2501,22 2976,22 trigger on third valve, case 20/09 S same model such as 20/09, silver plated 2779,73 3307,63 optional J.