Brass Maintenance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schagerl Instruments

SCHAGERL® PFLEGEHINWEISE, GARANTIEBESTIMMUNGEN & AGB (INSTRUCTIONS FOR CARE, GUARANTEE, TERMS AND CONDITIONS) Auf unserem Schagerl Video Channel www.youtube.com/SchagerlClub REGISTER NOW AND EXTEND YOUR WARRANTY PERIOD OF YOUR INSTRUMENT FROM 24 TO 36 MONTH! finden Sie unter der Playlist www.schagerl.com/instrumentenregistrierung Instrumentenpflege (Care Instructions for Instruments) Pflegeanleitungen als Video in Full HD! For all instruments acquired on or after 1 January 2016, the warranty period is extended to 36 months if and provided that the buyer registers these instruments within 8 weeks after the date of purchase. Registration can only be done online at www.schagerl.com/instrumentenregistrierung. Care Notes for Rotary Valve Instruments due to the extremely precise construction the rotary valve system, these procedures should be followed with care. EN 5 6 Care Products: 1 for the valves4Hetman Light Rotor 11* (or Schagerl Valve Oil) for the linkages4Hetman Ball Joint 15* (or Ultra Pure Linkage Oil) for the triggers4Hetman Slide Oil 5* for the slides4Hetman Slide Grease 8* (or Ultra Pure Regular) for the ball joint4Hetman Slide Grease 8* (or Ultra Pure Regular) We recommend a yearly instrument service at Schagerl Music Gmbh or one of our representatives. for the lacquer, silver and gold4Glass cleaner and a soft cloth i 2 Application: after every use: 1 drop Hetman Light Rotor in each upper valve post, 1 drop in lower valve post (unscrew bottom valve cap) , Slide Grease 6 8* on each slide. every 2 - 3 weeks: 1 drop Hetman Ball Joint on the mini-ball linkages , oil the cross braces 3rd slide with Hetman Slide Oil 5* , Lubri- 3 4 cate the other slides and linkages with Hetman Slide Grease 8* once a month: remove the main tuning slide and run water backwards through the valves towards the leadpipe while not moving the valves. -

BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE of FINE ARTS Dissertation MERRI FRANQUIN and HIS CONTRIBUTION to the ART of TRUMPET PLAYING by GEOFFRE

BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS Dissertation MERRI FRANQUIN AND HIS CONTRIBUTION TO THE ART OF TRUMPET PLAYING by GEOFFREY SHAMU A.B. cum laude, Harvard College, 1994 M.M., Boston University, 2004 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts 2009 © Copyright by GEOFFREY SHAMU 2009 Approved by First Reader Thomas Peattie, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Music Second Reader David Kopp, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Music Third Reader Terry Everson, M.M. Associate Professor of Music To the memory of Pierre Thibaud and Roger Voisin iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Completion of this work would not have been possible without the support of my family and friends—particularly Laura; my parents; Margaret and Caroline; Howard and Ann; Jonathan and Françoise; Aaron, Catherine, and Caroline; Renaud; les Davids; Carine, Leeanna, John, Tyler, and Sara. I would also like to thank my Readers—Professor Peattie for his invaluable direction, patience, and close reading of the manuscript; Professor Kopp, especially for his advice to consider the method book and its organization carefully; and Professor Everson for his teaching, support and advocacy over the years, and encouraging me to write this dissertation. Finally, I would like to acknowledge the generosity of the Voisin family, who granted interviews, access to the documents of René Voisin, and the use of Roger Voisin’s antique Franquin-system C/D trumpet; Veronique Lavedan and Enoch & Compagnie; and Mme. Courtois, who opened her archive of Franquin family documents to me. v MERRI FRANQUIN AND HIS CONTRIBUTION TO THE ART OF TRUMPET PLAYING (Order No. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75 Conference or Workshop Item How to cite: Smith, David and Blundel, Richard (2016). Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75. In: Association of Business Historians (ABH) and Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG) Joint Conference, 27-29 May 2016, Humbolt University, Berlin. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2016 The Authors https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://ebha.org/public/C6:pdf Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Joint Conference Association of Business Historians (ABH) and Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG), 27-28 May 2016, Humboldt University Berlin, Germany Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75 David Smith* and Richard Blundel** *Nottingham Trent University, UK and **The Open University, UK Abstract This paper examines the interplay between innovation and entrepreneurial processes amongst competing firms in the creative industries. It does so through a case study of the introduction and diffusion into Britain of a brass musical instrument, the wide bore German horn, over a period of some 40 years in the middle of the twentieth century. -

Care & Maintenance

Care and Maintenance of the Euphonium and Piston-Valve Tuba You Will Need: 1) Soft cloth (cotton or flannel) 4) Valve brush 2) Flexible brush (also called a “snake”) 5) Tuning slide grease 3) Mouthpiece brush 6) Valve Oil Daily Care 1) Never leave your instrument unattended. It takes very little time for someone to take it. 2) The safest place for your instrument is in the case. Leave it there when you’re not playing. 3) Do not let other people use your instrument. They may not know how to hold and care for it. 4) Do not use your case as a chair, foot rest or step stool. It is not designed for that kind of weight. 5) Lay your case flat on the floor before opening it. Do not let it fall open. 6) Do not hit your mouthpiece, it can get stuck. 7) Do not lift your instrument by the valves. Use the bell and any large tubes on the outside edge. 8) No loose items in your case. Anything loose will damage your instrument or get stuck in it. 9) Do not put music in your case, unless space is provided for it. If you have to fold it or if it touches the instrument, it should NOT be there. 10) Avoid eating or drinking just before playing. If you do, rinse your mouth with water before playing. 11) You may not need to do it every day, but keep your valves running smooth with valve oil. Put the oil directly on the exposed valve, not in the holes on the bottom of the casings. -

2017-System-Blue-Catalog.Pdf

2017 SYSTEM BLUE Excellence is in our DNA. Backed by over 100 years of experience and knowledge, System Blue proudly delivers the products and education many have only dared to imagine. Our team of designers has walked the very path you walk now. We are the same dedicated 2017 performers and educators that you are, and we’re turning our ideas into reality. We have stood in your shoes and marched the PROFESSIONAL PERCUSSION 2 same fields. We know you. We ARE you. You are TRADITIONAL PERCUSSION 10 not alone, and you never were. System Blue ON2 PERCUSSION SLIPS 12 empowers us all to reach our greatest potential. STANDS & CARRIERS 14 DRUM STICKS & BAGS 16 TOGETHER, MALLETS & BAGS 18 IT’S OUR TIME. PROFESSIONAL BRASS 20 TRADITIONAL BRASS 28 MOUTHPIECES 32 SOUND REINFORCEMENT 34 DRILLMASTERS & APPAREL 36 EDUCATION/MANAGEMENT 38 EDUCATION/EVENTS 40 HEALTH & WELLNESS 42 DESIGN QUALITY & COMMITMENT 44 SYSTEM BLUE DESIGNERS 45 TESTIMONIALS 46 PROFESSIONAL PERCUSSION EVOLUTIONARY. System Blue Natal Professional Marching Percussion Series is like no other product on the market. These drums are lightweight, built for speed with the player’s health and wellness in mind. The rich, smooth, and resonant voices blend and project in any venue. Each instrument is aesthetically beautiful, eye-catching, and, in a word — elegant. While there have been evolutions in marching percussion in the last 50 years, there has never been design and innovation like the System Blue Natal Professional Marching Percussion Series. We’ve fine-tuned and streamlined every detail, and the results are extraordinary. 2 SYSTEM BLUE • 2017 systemblue.org 3 PROFESSIONAL PERCUSSION It’s the LIGHTEST marching snare on the market.. -

Band Director's Catalog

BAND DIRECTor’s CATALOG We make legends. A division of Steinway Musical Instruments, Inc. P.O. Box 310, Elkhart, IN 46515 www.conn-selmer.com AV4230 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Eb Soprano, Harmony & Eb Alto Clarinets ....... 10 Bb Bass, EEb Bass & BBb Bass Clarinets ........... 11 308 Student Instruments Step-Up & Pro Saxophones .............................. 12-13 Step-Up & Pro Bb Trumpets .............................. 14 Piccolos & Flutes ...................................................... 1 Step-Up & Pro Cornets ..................................... 14 Oboes & Clarinets .................................................... 2 C Trumpets, Harmony Trumpets, Flugelhorns .... 15 Saxophones .............................................................. 3 Step-Up & Pro Trombones ................................ 16-17 204 Trumpets & Cornets .................................................. 4 Alto, Valve & Bass Trombones .......................... 18 Trombones ............................................................... 5 Double Horns .................................................. 19 PICCOLOS Single Horns ............................................................ 5 Baritones & Euphoniums .................................. 20 Educational Drum, Bell and Combo Kits .................. 6 BBb Tubas - Three Valve .................................... 21 ARMSTRONG Mallet Instruments .................................................... 6 BBb & CC Tubas - Four Valve ............................ 21 204 “USA” – Silver-plated headjoint and body, silver-plated -

WIND INSTRUMENTS from the Hands of Our Artisans…

WIND INSTRUMENTS From the Hands of our Artisans… You’ll find our instruments in the hands of musicians from all and it makes no difference as to whether the instrument is a custom ages and levels all over the world. Whether we are making a pro level instrument, or a student model for a beginner. Constantly in professional level instrument or a student model, our aim is to contact with the instruments we make, we are concerned with what provide the musician with an instrument that sounds and plays as goes into them since it not only affects their sound and playability, best as possible, is reliable, and is good for both the user and the but the player and the environment as well. That’s why Yamaha environment. instruments are made using lead-free solder. When you pick up a Yamaha instrument, take a moment and think Much like making music, crafting instruments is an art that requires about how this instrument made it into your hands. How it started dedication and a passion for perfection. Through our art, we bring from a sheet of metal or length of seasoned wood, was shaped into the instrument to form, through the musician’s art, that form comes form by the skilled hands of a master craftsman, then assembled and to life. We take great pride in passing our art on to musicians young adjusted, again by hand. Yes, by hand. and old, and watching them mature and bloom with the products we With all of the advanced technologies we have at our disposal, we still make. -

2019-System-Blue-Catalog.Pdf

SYSTEM BLUE Excellence is in our DNA. Backed by over 100 years of experience and knowledge, System Blue proudly delivers the products and education many have only dared to imagine. Our team of designers has walked the very path you walk now. We are the same dedicated performers and educators that you are, and we’re turning our ideas into reality. We have stood in your shoes and marched the PROFESSIONAL PERCUSSION 2 same fields. We know you. We ARE you. You are CONCERT PERCUSSION 10 not alone, and you never were. System Blue ON2 PERCUSSION SLIPS 16 empowers us all to reach our greatest potential. STANDS & CARRIERS 18 DRUM STICKS & BAGS 20 TOGETHER, MALLETS, BAGS & HEADS 22 IT’S OUR TIME. PROFESSIONAL BRASS 24 TRADITIONAL BRASS 32 MOUTHPIECES 36 SOUND REINFORCEMENT 38 HEALTH & WELLNESS 40 DRILLMASTERS 41 SYSTEM BLUE EDUCATION 42 EDUCATIONAL EVENTS 44 DESIGN QUALITY & COMMITMENT 46 SYSTEM BLUE DESIGNERS 47 TESTIMONIALS 48 PROFESSIONAL PERCUSSION EVOLUTIONARY. System Blue Professional Marching Percussion Series is like no other product on the market. These drums are lightweight, built for speed with the player’s health and wellness in mind. The rich, smooth, and resonant voices blend and project in any venue. Each instrument is aesthetically beautiful, eye-catching, and, in a word — elegant. While there have been evolutions in marching percussion in the last 50 years, there has never been design and innovation like the System Blue Professional Marching Percussion Series. We’ve fine-tuned and streamlined every detail, and the results are extraordinary. 2 SYSTEM BLUE • 2017 systemblue.org 3 PROFESSIONAL PERCUSSION It’s the LIGHTEST marching snare on the market.. -

Wind Instruments Catalog.Pdf

Wind Instruments What has made YAMAHA the number one musical instrument manufacturer in the world? Continuous R&D We are the only instrument maker who maintains a complete staff of experienced, fulltime designers for each individual wind instrument. And we station part of that staff in Europe, North America, as well as Japan to maintain constant communication with many of the greatest musicians now performing. The ideas and insights we receive from the masters are relayed back to our design center, where they are incorporated into every instrument we make. Manufacturing Quality We make most of the individual components for our woodwind and brass instruments with cutting-edge, computerized technology for perfect tolerances and incredible consistency. But many visitors to our factories are surprised to see the large degree of age-old, traditional methods used to hand assemble all our wind instruments— from professional models down to the most inexpensive student instruments. Crafted With Care Skilled, experienced artisans adjust and test each instrument by hand—and do so with a passion and care seldom seen anymore. Many of them are musicians themselves; they joined Yamaha because of their love for music. Producing the world’s finest musical instruments is more than just a job for them; it is a calling, and a challenge they meet with pride. Yamaha Wind Instrument History In 1887, Torakusu Yamaha began producing reed organs in Hamamatsu, in central Japan. He later founded a company called Nippon Gakki (Musical Instruments of Japan). Around the same time, a Tokyo boilermaker began making bugles and established a wind instrument company named Nippon Kangakki (Japanese Wind Instruments). -

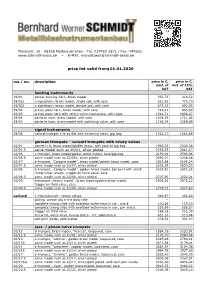

Price List Valid From: 01.01.2020

Mosenstr. 10 - 08258 Markneukirchen - Tel. 037422 2871 / Fax -749631 www.schmidt-brass.de - E-Mail: [email protected] price list valid from: 01.01.2020 mo./ no. description price in €, price in €, excl. of incl. of 19% VAT VAT hunting instruments 19/01 pocket hunting-horn, brass model 351,72 418,52 19/021 c-signalhorn, brass model, single coil, with case 651,92 775,73 19/022 c-signalhorn, brass model, double coil, with case 674,33 802,39 19/02 prince pless horn, brass model, with case 716,91 853,06 19/03 prince pless horn with rotary valve mechanism, with case 1544,71 1838,07 19/04 parforce horn, brass model, with case 1438,29 1711,44 19/05 parforce horn, brass model with switching valve, with case 1756,34 2089,89 signal instruments 19/08 natural trumpet in b-es flat with switching valve, gig bag 1062,17 1263,89 german trumpets – concert trumpets with rotary valves 20/01 cornet in b, brass model/golden brass, with case or gig bag 1965,35 2338,56 20/01 S same model such as 20/01, silver plated 2236,53 2661,27 20/05 c-trumpet, brass model/golden brass model, case/gig-bag 2159,04 2569,06 20/05 S same model such as 20/051, silver plated 2696,07 3208,08 20/07 b-trumpet, “Cologne model”, brass model/golden brass model, case 1923,88 2289,24 20/07 S same model such as 20/07, silver plated 2202,29 2620,53 20/08 b-trumpet, „Cologne model”, golden brass model, bell joint with small 2429,81 2891,25 nickel silver wreath, trigger on third valve, case 20/08 S same model such as 20/08, silver plated 2707,95 3222,21 20/09 b-trumpet „Heckel model“, brass model/golden brass model, 2501,22 2976,22 trigger on third valve, case 20/09 S same model such as 20/09, silver plated 2779,73 3307,63 optional J. -

The Evolution of the Bugle

2 r e The evolution t p a h C of the bugle by Scooter Pirtle L Introduction activity ponders how it will adapt itself to the ceremonies, magical rites, circumcisions, When one thinks of the evolution of the future, it may prove beneficial to review the burials and sunset ceremonies -- to ensure bugle used by drum and bugle corps, a manner by which similar ensembles that the disappearing sun would return. timeline beginning in the early 20th Century addressed their futures over a century ago. Women were sometimes excluded from might come to mind. any contact with the instrument. In some While the American competitive drum and A very brief history of the Amazon tribes, any woman who even glanced bugle corps activity technically began with trumpet and bugle at a trumpet was killed. 2 Trumpets such as the American Legion following the First through the 18th Century these can still be found in the primitive World War (1914-1918), many innovations cultures of New Guinea and northwest Brazil, had already occurred that would guide the L Ancient rituals as well as in the form of the Australian evolution of the bugle to the present day and Early trumpets bear little resemblance to didjeridu.” 3 beyond. trumpets and bugles used today. They were Throughout ancient civilization, the color Presented in this chapter is a narrative on straight instruments with no mouthpiece and red was associated with early trumpets. This important events in the evolution of the no flaring bell. Used as megaphones instead could probably be explained by the presence bugle. -

Trumpet Cornet Pocket Trumpet Trumpet Cornet Pocket Trumpet

TrumpetTrumpet CornetCornet PocketPocket TrumpetTrumpet Owner’s Manual Precautions 2 After Playing 8~11 Maintenance goods 2 1. Valve Slide Maintenance 8 Nomenclature 3 2. Maintenance for Pistons and Valve Caings 10 Before playing 4~7 3. Body Maintenance 11 1. Applying Oil to the Piston 4 Others 12 2. Setting the Mouthpiece 5 1. Caution for Strage 12 3. Holding the Instrument 5 2. Cleaning the Instrument 12 4. Press the Pistons 6 Fingering chart 14~15 5. Placing the Instrument 7 6. Tuning 7 Thank you for purchasing “J. Miachael” instrument. For instructions on the proper assembly Nomenclature of the instruments, and how to keep the instruments in optimum condition for as long as possible, we urge you to read this Owner’s manual thoroughly. The precautions given below concern the proper and safe use of the instrument, and are to ●Trumpet 1st Valve Bell protect you and others from any damage or injuries. Please follow and obey these 2nd Valve precautions. Valve Cap 3rd Valve Mouthpiece Caution Mouthpiece Receiver Main Tuning Slide ●Keep the oil, small parts, etc., out of ●Do not throw or swing the instrument. 1st Valve Slide Water Key children’s mouths and do maintenance The mouthpiece or other parts may fall 2nd Valve Slide Stopper Screw when children are not present. off hitting other people. 3rd Valve Slide Valve Casing Bottom Cap ●Take care not to disfigure the instrument. ●Do not modify the instrument. Besides Placing the instrument where it is voiding the warranty, modification of the unstable may cause the instrument to fall instrument may make repairs impossible.