Download Full Issue In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section 1201 Rulemaking: Seventh Triennial Proceeding to Determine

united states copyright office section 1201 rulemaking: Seventh Triennial Proceeding to Determine Exemptions to the Prohibition on Circumvention recommendation of the acting register of copyrights october 2018 Section 1201 Rulemaking: Seventh Triennial Proceeding to Determine Exemptions to the Prohibition on Circumvention Recommendation of the Acting Register of Copyrights TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 1 II. LEGAL BACKGROUND ..................................................................................................... 9 A. Section 1201(a)(1) ............................................................................................................. 9 B. Relationship to Other Provisions of Section 1201 and Other Laws ........................ 11 C. Rulemaking Standards ................................................................................................. 12 D. Streamlined Renewal Process ...................................................................................... 17 III. HISTORY OF SEVENTH TRIENNIAL PROCEEDING ................................................ 20 IV. RENEWAL RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................................................... 22 V. DISCUSSION OF NEW PROPOSED CLASSES ............................................................. 31 A. Proposed Class 1: Audiovisual Works—Criticism and Comment ......................... 31 B. Proposed Class 2: Audiovisual -

Peter Seaton

AGREEMENT PETER SEATON AGREEMENT Peter Seaton AsylumQs Press New York New York Versions of these works have appeared in This, Roof and Slit Wrist. (c) 1978 by Peter Seaton PERSUASION These pens were fondled by the dark white man Who came to the house in the middle of the morning and now Wants to come all the way to New York To see them again, the blue the pink, the green Waiting to be used as independently as each successive April Marks off moments the sun has chosen to forget In our extremities of helplessness: one brief, And one shrugging its shoulders As absence makes the heart grow with a jolt Into the wilderness. The burden Is a promiseo The gold Over the next hill buys less or more According to the make or model of the following year: One with a solid stripe providing the comfort Of the invisible line between the lenses, one Whose fragility was as awesome as legs spread Confidently after a sleepless night. The promise Was to breed with or without the demarcation of The lengthy phrase "to earn a living", the helplessly long Password behind the rolling spotlight As it illuminates the terrible address our residence Identifies for one interminable summer and each successive Late afternoono We fly to New England For Thanksgiving, to Miami for Easter, To California to practice law and Paris To be acknowledged as heirs to the role Of making women everything they could become, the promise Of a world perennially between the wars. Instead 3 The pens are fondled nervously, itching To leap into action as if writing were the legacy Of the nineteenth century, the wars between the words Harmlessly occupying the fringes of space While nimble fingers sew and stretch the Earth Into recognizable activity, The struggle of a promise smoothly determined as much By clear-cut instructions for the arrangement of this Anniversary as by the tension misplaced implements Form in our mouths and on paper. -

Program Abstracts

University of Montana Presents The 15th Annual Program and Abstracts April 15, 2016 ~ Missoula, Montana Program Design: University of Montana, Conference Planning Services www.umt.edu/sell/cps Undergraduate Research Committee: Brock Tessman (Chair), Davidson Honors College Susanne Bradford, Applied Arts & Sciences Abhishek Chatterjee, Political Science Dan Doyle, Sociology Amy Glaspey, Communicative Sciences & Disorders John Glendening, English Karen Jaskar, Mansfield Library Andrew Larson, Forest Management Scott Samuels, Biological Sciences James Sears, Geosciences Ex Officio Members Earle Adams, Chemistry Nathan Lindsay, Academic Affairs Andrea Rhoades, Academic Enrichment Megan Stark, Mansfield Library Wendy Walker, Mansfield Library Scott Whittenburg, Research & Creative Scholarship Conference Coordinators: Michelle Eckert, CPS - School of Extended & Lifelong Learning Karen Kaley, Davidson Honors College Jeanne Loftus, Global Leadership Initiative Michelle Quinn, CPS - School of Extended & Lifelong Learning Technology, Trainings & Support: Cohen Ambros, Writing Center Glenn Kneebone, UM Paw Print Marissa Lehner, Davidson Honors College Robert Logan, Davidson Honors College IT Gretchen McCaffery, Writing Center Laure Pengelly Drake, Davidson Honors College Megan Stark, Mansfield Library Wendy Walker, Mansfield Library Kelly Webster, Writing Center Website & Facebook Maintained by: Michelle Eckert, CPS - School of Extended & Lifelong Learning Special thanks to all the mentors, reviewers, judges, and volunteers who donated their time! -

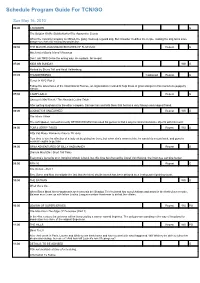

Sydney Program Guide

Page 1 of 38 Sydney Program Guide Sun Nov 11, 2012 06:00 THUNDERBIRDS Repeat WS G Attack of the Alligator Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:00 KIDS WB SUNDAY WS G Hosted by Lauren Phillips and Andrew Faulkner. 07:00 CHOWDER Repeat WS G Gazpacho/The Toots Chowder needs someone to grace the cover of the first issue of his home-made magazine. MARVELOUS MISADVENTURES OF 07:30 Repeat WS G FLAPJACK II Who’s that Man in the Mirror/Unhappy Endings K’nuckels has gotten extremely out of shape and may lose Flapjack because of it. 08:00 THUNDERCATS Repeat WS PG New Alliances The 'Cats battle Mumm-Ra's lizard army; Panthro receives a new set of robotic arms. Cons.Advice: Mild Violence 08:30 BEN 10: OMNIVERSE WS PG It Was Them Dr. Amino escapes prison, putting the world in danger of becoming a mutant-ant farm. Cons.Advice: Stylised Violence 09:00 THE SECRET SATURDAYS Repeat WS PG Eterno The Secret Scientists have combined their brainpower to solve a developing global crisis: water supplies in the Middle East are inexplicably turning into salt. 09:30 THE SECRET SATURDAYS Repeat WS PG Black Monday After Zak touches the mystic Smoke Mirror of Tezcatlipoca, he discovers he's unleashed an evil doppelganger: Zak Monday. And when Drew starts acting strangely, Zak fears that his bad double may not be the only one who came out of that mirror. 10:00 BATMAN: THE BRAVE AND THE BOLD Repeat WS PG Sword of the Atom! After a visit to the Currys, Batman looks for an old friend, the Silver Age Atom, in the jungles of the Amazon. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title "Through the Eyes": Reading Deafened Gestures of Look-Listening in Twentieth Century Narratives Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4h17630k Author Cardinale, Cara Lynne Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE ―Through the Eyes‖: Reading Deafened Gestures of Look-Listening in Twentieth Century Narratives A Dissertation Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Cara Lynne Cardinale June 2010 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Katherine Kinney, Chairperson Dr. Kimberly Devlin Dr. Traise Yamamoto Copyright by Cara Lynne Cardinale 2010 The Dissertation of Cara Lynne Cardinale is approved: ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments In ―A Room of One‘s Own‖ Virginia Woolf writes: ―For masterpieces are not single and solitary births; they are the outcome of many years of thinking in common, of thinking by the body of people so that the experience of the mass is behind the single voice.‖ This revelation—forged in a twinned hammered steel bangle I wear around my wrist as a reminder— has made completing this dissertation possible. Five years, seven countries and one birth later I have found my voice depends on a larger body of support. Academically, I have been supported by a tremendous dissertation committee. Katherine Kinney, an enduring and encouraging chair, trusted in my vision of language and the body even as an eclectic masters portfolio looking at Beowulf and Brando. Her willingness to travel the scenic route with me through draft after draft and encourage the birth of this dissertation has been indispensible. -

Program Guide Report

Schedule Program Guide For TCN/GO Sun May 16, 2010 06:00 CHOWDER G The Belgian Waffle Slobberbarker/The Apprentice Scouts When the catering company is robbed, the gang cooks up a guard dog. But Chowder modifies the recipe, making the dog turns more dangerous than not having any protection. 06:30 THE MARVELOUS MISADVENTURES OF FLAPJACK Repeat G Mechanical Genie Island / Revenge Dont rub THIS Genie the wrong way. Hes playin for keeps! 07:00 KIDS WB SUNDAY WS G Hosted by Shura Taft and Heidi Valkenburg. 07:05 THUNDERBIRDS Captioned Repeat G Terror In NYC Part 2 Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:30 CAMP LAZLO Repeat G Samson's Mail Fraud / The Haunted Coffee Table After getting laughed at by the other campers, Samson lies and tells them that he has a very famous and magical friend. 08:00 LOONATICS UNLEASHED Repeat WS G The Music Villain The soft-spoken, somewhat nerdy KEYBOARD MAN has used his genius to find a way to control inanimate objects with his music. 08:30 TOM & JERRY TALES Repeat WS G Kitty Cat Blues/ Flamenco Fiasco/ DJ Jerry Tom tries to win the affection of a lady cat by giving her Jerry, but when she's mean to him, he wants his mouse back, and goes to musical lengths to get him. 09:00 GRIM ADVENTURES OF BILLY AND MANDY Repeat G Dracula Must Die / Short Tall Tales Everyone's favourite O.G. (Original Ghoul) is back, but this time he's hunted by Lionel Van Helsing, the infamous vampire hunter. -

Program Guide Report

Schedule Program Guide For TCN/GO Sun Jun 17, 2012 06:00 THUNDERBIRDS Repeat WS G End Of The Road Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:00 KIDS WB SUNDAY WS G Hosted by Lauren Phillips and Andrew Faulkner. 07:00 SCOOBY DOO AND THE GHOUL SCHOOL 1988 Repeat G Scooby Doo and the Ghoul School Shaggy and Scooby accept jobs as physical education instructors at a girls' finishing school, and before you can say, "Pass the Scooby snacks," the Mystery Machine crew of sleuths realize that they might be the ones who'll soon be finished. 09:00 THUNDERCATS Repeat WS PG Berbils A group of robot bears need help from the ThunderCats. Cons.Advice: Mild Violence 09:30 YOUNG JUSTICE Repeat WS PG Welcome to Happy Harbor Speedy refuses to join the team, causing the others to question whether the League takes them seriously. The emergence of a new villain, Mr. Twister, forces them to band together and determine if they can work together... while trying to survive. Cons.Advice: Mild Violence 10:00 BATMAN: THE BRAVE AND THE BOLD Repeat WS PG The Last Patrol! The outsider-heroes The Doom Patrol are pulled out of a hasty retirement when supervillains begin trying to assassinate them, or perhaps re-unite them? Cons.Advice: Mild Violence 10:30 BEN 10: ULTIMATE ALIEN Repeat WS PG Where The Magic Happen Hot on Aggregor's trail, Ben and company wind up in a magical realm where they must rely on Charmcaster for help. -

Restorative Nursing Program (RNP)

1 Restorative Nursing Program Certifi cation Course 2007 MANUAL Great care begins with you! 2 Restorative Nursing Program Certifi cation Course 2007 This project was created in the Public Domain and is freely available to any training provider that wishes to use it. For additional information and to access proof copies of the Program Materials, please contact: Quality Care Health Foundation 2201 K Street Sacramento, CA 95816 916 441.6400, ext. 210 http://www.qchf.org Updated September, 2011 This textbook has been laid out in Adobe InDesign CS 3.0.1 using 12-point Arial body type. 3 Restorative Nursing Program Certifi cation Course 2007 Congratulations! Congratulations on your decision to become certifi ed in the Restorative Nursing Program! You have made a great decision. Your involvement in this course will assure that the residents in your facility receive care that enables them to function as independently as possible. You will also benefi t by learning the most effective resident management techniques while protecting yourself from personal injury. We know that you are dedicated to the residents in your facility. How do we know this? We know because you are here to improve your skills. And when you improve your skills, your residents benefi t. Thank you for participating in this Restorative Nursing Program Certifi cation Course. Great care begins with you! 4 Restorative Nursing Program Certifi cation Course 2007 How this class was created The Restorative Nursing Certifi cation Program (RNCP) started as a dream, developed by a group of therapy and nursing professionals who knew that there had to be a better way to train Restorative CNAs for their critical work with the elder population. -

LYNX a Journal for Linking Poets XXII:3 October, 2007 Table Of

LYNX A Journal for Linking Poets XXII:3 October, 2007 Table of Contents SYMBIOTIC POETRY A PLATE BETWEEN US by Lynne Rees, Wales (lynne) Jim Wilson, USA, (dharmajim),Moira Richards, South Africa (moi),Karen Cesar, USA (karen),Raihana Dewji, USA (sbasil),CW Hawes, USA (chris), Kala Ramesh, India (kala), Josh Wikoff, USA (lemonkind),Norman Darlington, Ireland - sabaki (norman),with a hokku by Matsuo Basho (tr. Darlington): BLUE PETER CONSIDERS by Dick Pettit, Diane Webb, Frank Williams & Francis Attard JUNETEENTH by Suhni Bell & Cindy Tebo DARK EARTH by Patricia Prime & Andre Surridge MORNING TRAIN by Patricia Prime & Andre Surridge NIGHT PLAGUE: ZOMBIE HORRORS by Lewis Sanders & Carl Brennan SKULL VALLEY by Zack Lyon & Richard Tice THE UNMADE BED by David Giacalone & CarrieAnn Thunell CALM MORN, WARM BED by CarrieAnn Thunell & Steven Thunell WALKING BUDDHA byFrancis Attard & Dick Pettit 2006 by Francis Attard & Dick Pettit THE MOWER'S BLADES by Jill Arthey, Sarah Barker, Margaret Dowdeswell, Sue Dunne, Alec Finlay, Linda France (Master), Malcolm Green, Beth Knowles, Alicia Lester, Ros Normandale, Carole Reeves, Tom Richardson, Christine Taylor SOLO WORKS GHAZALS I'VE BECOME C.W. Hawes SAILING Ruth Holzer GHAZAL OF THE STARTLED SILENCE Steffen Horstmann ACROSS THE BAY Steffen Horstmann 10:30 A.M. Elizabeth Snider NIGHT DESCENT Richard Tice HAIBUN THE ROAD by c w hawes NOON by Charles Hansmann SELF-PORTRAIT IN PLATE GLASS by Charles Hansmann CAUSE AND EFFECT by Charles Hansmann FOOTNOTE TO THE SCROLLS by Charles Hansmann WORKING MAN by Roger Jones ON BERKELEY WAY by Tracy Koretsky DOG STAR by Ray Rasmussen WHAT ARE YOU UP TO? by Ray Rasmussen AHAPOETRY.COM by Jane Reichhold WHERE DID YOU GO? OUT… by Richard Straw STILLby Jeffrey Woodward IN THE COMPANY OF THE CLOUDS by Jeffrey Woodward THROUGH THE CALM by Jeffrey Woodward SEQUENCES GIRL WITH A PEARL EARRING by Edward Baranosky LITHOGRAPH BY KAETHE KOLLOWITZ, 1942 by Edward Baranosky INTERLUDE: SUNSET by Carl Brennan UNTITLED by Gerard John Conforti GARDEN AND MOUNTAIN by Glenn R. -

May 2017, Crips in Space Guest Editors' Note by Alice Wong and Sam De Leve Greetings, Corpore

1 The Deaf Poets Society, Issue 4: May 2017, Crips in Space Guest Editors’ Note by Alice Wong and Sam de Leve Greetings, corporeal crips and non-crips: As guest editors for this special issue of The Deaf Poets Society, we are excited and honored to share the brilliant creations and perspectives offered by contributors to this issue. Crips in Space was conjured by a mundane activity: Sam had reconceptualized their movement on wheels as an analogue to movement in zero-gravity, which in turn sparked speculation about the ways in which crips are particularly suited to life in space. Their tweet about #CripsInSpace went viral when Alice amplified it and encouraged community input. The outpouring of interest from dozens upon dozens of people serves to highlight not only our enduring fascination as a species with space, but also how strongly speculation about the future resonates with d/Deaf and disabled people in particular. As more and more people suggested artmaking around this theme, Alice proposed a collaboration with The Deaf Poets Society. The expertise and interest of The Deaf Poets Society and its editors allowed the burgeoning 2 idea of Crips in Space to come to life here in this issue. We are filled with gratitude for this opportunity and partnership. While space may exist in a vacuum, the idea of Crips in Space did not come from a cultural vacuum: indeed, it can trace its roots to a long history within speculative fiction and within the d/Deaf and disability community. Despite the erasure or diminishment of d/Deafness and disability in major touchstone media, it is far from absent. -

The Barber (^Seinfeld) from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

:rhe Barber (Seinfeld) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of2 The Barber (^Seinfeld) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia "The Barber" is theT2nd episode of the NBC sitcom Seinfeld.It is the eighth episode of the fifth "The Barber" season, and first aired on November ll,1993. Seínfeld episode Plot Episode no. Season 5 Episode 8 The episode begins with George at ajob Directed by Tom Cherones interview. His future employer, Mr. Tuttle, is cut Written by Andy Robin off mid-sentence by an important telephone call, and sends George away without knowing whether Production code 508 he has been hired or not. Mr. Tuttle told George Original air date November ll,1993 that one of the things that make George such an Guest actors attractive hire is that he can "understand everything immediately", so this leaves apuzzling situation. In Jerry's words: "If you call and ask if Wayne Knight as Newman Antony Ponzini as Enzo you have the job, you might lose the job." But if David Ciminello as Gino George doesn't call, he might have been hired and Michael Fairman as Mr. Penske he never know. George will decides that the best Jack Shearer as Mr. Tuttle course of action is to not call at all and to just "show up", pretending that he has been hired and Season 5 episodes start "work", all while Mr. Tuttle is out of town. The thought behind this was that if George has the September 1993 -May 1994 job, then everything will be fine; and if George uThe was not hired, then by the time Tuttle returns, he 1. -

TELLING TIME: Reflections on a Life in Music Stanley Walden

TELLING TIME: Reflections on a Life in Music Stanley Walden For Rhonda TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface i Introduction iii Chapter 1 1967-69: The Road to Calcutta! 1 Chapter 2 1932-39: Another Brooklyn Story 8 Chapter 3 1940-50: Schools and Friends. And Others. 11 Chapter 4 1950-55: College: Becoming a Musician 27 Chapter 5 1955-57: The Draft, and a Proposal 39 Chapter 6 1957-68: New York: Two Kids with Two Kids 56 Chapter 7 1968-70: Oh! Calcutta! 73 Chapter 8 1970-71: First Work with Tabori--Pinkville 81 Chapter 9 1972-89: Hin und Her (Back and Forth) 85 Chapter 10 1989-2003: HdK Berlin, Munich, Vienna 114 Chapter 11 2003-2012: Retirement: Palm Springs 126 Chapter 12 2012-2014: 60 Years--Final Curtain & Encore 132 Chapter 13 2014-16: The Goldberg Variations 136 Chapter 14 2015-16: 55 Years--Another Final Curtain 138 Chapter 15 Reflections 140 Appendices 1 Sons 143 2 Musings and Jottings by Bobbie Walden as she 145 approached her death 3 Close (and Closer) Calls 151 4 Thoughts on Improvisation 155 5 Some Observations by an American Acting in the 159 German Theater (1984) Index 164 i Preface: Talking to the Wrong End of the Dog When I met Stanley Walden, I didn’t know much about music. Now, three years later, I know a little more about music, but only a little. My mother warned me that I’d regret quitting piano lessons when I was nine, and sure enough, I do. What I do know a lot more about now than before I met Stan Walden, though, is musicians.